There was an old Chinese man the locals called “No Chin”. He had exposed dentures and he slept on cornbags in a shed in Elgin Street, behind the iceworks. There was Billy Kilmartin, who rode around on a pushbike at night with a covered basket on his handlebars, selling hot pies. And there was Jackie Minch, whose mother had a grocery shop and who ran to the bank with every pound note they earned, wearing a felt hat turned up like Tiger Kelly.

These and other colourful characters from Maitland in the 1920s and 1930s clung to life in the memory of Neville Chant, an engaging centenarian whose recollections of his early times kept me spellbound for hours at a time when I met him in 2019.

Growing up on Belmore Road, Lorn, was interesting for an observant youngster like Neville. He remembers the floods, in particular, because when the river rose up his parents would take him to look, and he has never forgotten the loud sound of big uprooted trees banging into the Belmore Bridge – the old iron bridge – as the angry yellow water of the swollen river hurled them downstream. “In those days the river was less silted up, and it used to peak at 37 or 38 feet. Even at a distance you could feel the shudder through the ground as the big trees hit the bridge,” Neville recalled. “Fellows used to get into the bridge with a rope and a wire hook and catch produce as it came down the river: melons and grammas and so on. They took their lives into their hands. I remember seeing lots of tree branches forced up against the side of the bridge by the water.”

During the 1932 flood (not long after Neville had started high school) he was on the last train that got through to Maitland Station, through water from Regent Street. “We were stopped on the Wallis Creek rail bridge before Maitland Station and they were afraid the train might not get through if the firebox was in the water. But the kids from Singleton got home all right. There were hundreds of kids from up that way on the trains in those days,” Neville said. “The river was a metre below the top of the levee behind the shops in High Street, and as dead animals were forced against the bridge men were pushing their bodies under the water to keep them going downstream.”

“In the 1955 flood I wasn’t in Maitland but I had to go there because my brother’s wife was assistant matron at Maitland Hospital and she wanted her kids taken to Mayfield. The flood co-ordinator, Lester Saddington, gave me permission to go up provided I took three big burly policemen with me. We took my little Vauxhall out the back way through Minmi, through paddocks and whatnot. We got through. At East Maitland the water was nearly up to the Melbourne Street corner, which was as far as you could got. The biggest problem was the looting that was going on,” Neville said.

For more stories about the 1955 flood in Maitland click here and here.

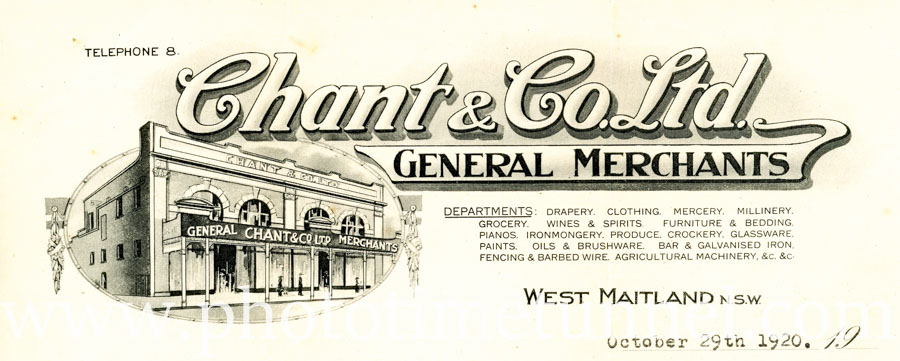

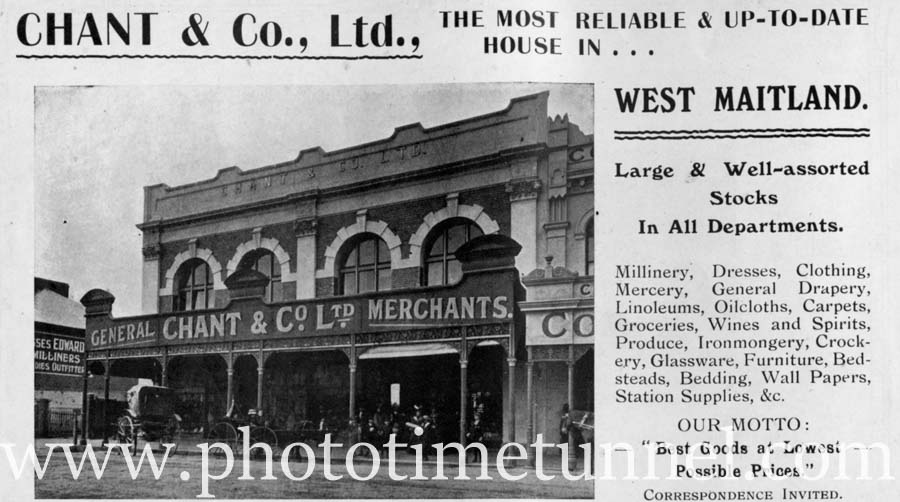

Neville’s grandfather and father ran the well-known Chant’s store in High Street, putting their family name to a business that was owned by some Jewish business people from Sydney. Chant and Co was a comprehensive store, selling ironmongery (hardware), kitchenware, confectionery, groceries, drapery, millinery, menswear, paint, horseshoes, carbide for gas, linseed oil and turpentine, Neville recalled.

“We sold petrol in four gallon cans from a separate shed that was sunk into the ground. Another shed was full of Schweppes cordials. There was Orange Pilato and Sato – which was similar to cola. We had a bulk warehouse with perhaps 40 or 50 cases of tins of jam – six dozen tins to a case, lashed with wire and very heavy. These were two-pound tins in huge variety: there were seven types of plum jam, there was melon, apricot, blackberry. It all came from Tasmania and arrived by rail at Maitland Station At Christmas the hams would come in, perhaps 150 16-pound hams in calico bags with husks on and you cooked them yourself in the family copper. You peeled the skin off and covered them in breadcrumbs,” he said.

Freight up-river to Morpeth

“A lot of freight came up by boat to Morpeth and was then brought over via David Cohen’s warehouse near the Town Hall. Sugar came to Morpeth in 72-pound bags and we had to bag it in paper if we weren’t serving the counter. We scooped it into the paper bags and tied them down for the shelves. Across from the sugar area at Chant’s was an old fellow who had corn, bran, wheat, oats and potatoes and his job was to weigh it up in paper bags and tie it with string.”

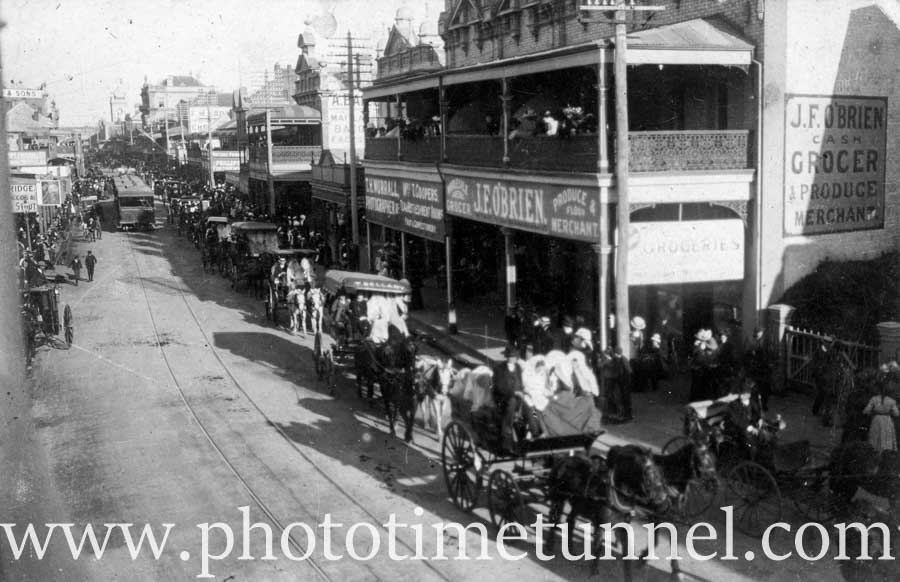

“Chant’s was the biggest of the general merchants, but there were others, including J.F. O’Brien, McIlraith’s near Church Street, Wolfe and Co and M.T. O’Brien.”

“There were four produce merchants: O.K. Young, Pryde’s, Kirkwood’s and W. C. Cain’s, all within half-a-mile of each other between the station and Church Street. It was a good business because everybody had horses and buggies and needed chaff, bran and oats in bulk sacks.”

Neville said there were at least six barbers in High Street and all did a good trade. “You always had to wait. I remember they had old-fashioned spittoons.”

“In the area opposite the Belmore Hotel could be found Frank Smith the auctioneer and second-hand dealer. Above and behind him was Frank Boyes the chiropodist and next to him was Keech’s bicycle shop. There were lots of bike shops, including Fitness, Bennett and Wood – who sold Speedwells and motorbikes – and Firths who made the Royal brand bike.”

“Next to Keech’s was Ellis’s cafe, with marble tables and cast iron chairs,” Neville recalled. “Apart from butchers that cafe had the only cool-room in Maitland. When the butter came in from Dungog the grocers had to buy it in 52-pound boxes from Ellis’s. Neville would carry a box on his bike and then store it in an icebox. Next along was Carroll’s music shop, then A. and O. Carruthers auctioneers and then Advanx Tyres.”

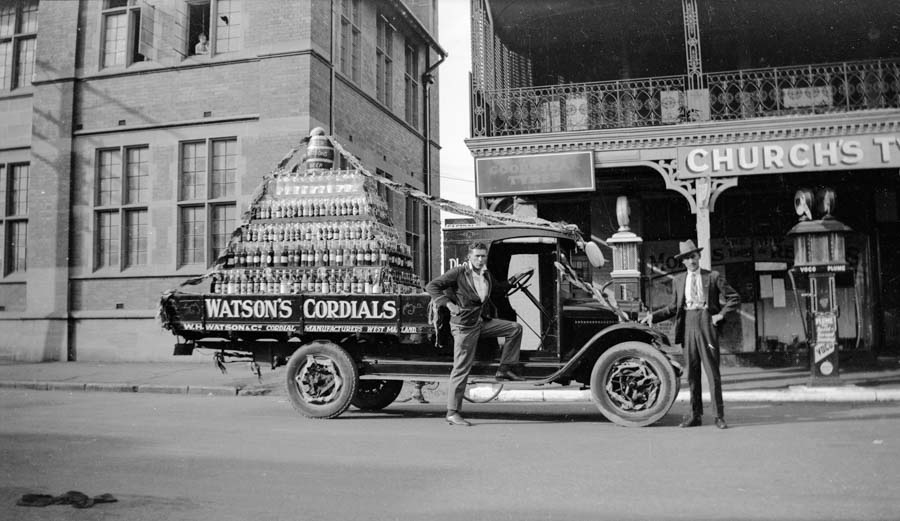

Neville said it was too expensive to bring cordials from Newcastle by train, so there were factories in Maitland: W. G. Watson and R.F. Heads. Watsons was in Church Street, flanked by Cracknell the baker and O.K. Young’s warehouse. Heads was next to Maitland iceworks.

The vendors did their daily rounds with horses and carts. You had the baker and butcher every day and the postie and milko twice a day. Nobody had refrigerators and all the milk was delivered in bulk.

“We had bread that used to turn up at the sides and you had to cut your own slices. They were tin loaves, rounded at the top and square at the back. You had two slices with cold roast beef or corned meat or if things weren’t too good it might be marmalade or a handful of dates. You enjoyed it because you knew some kids didn’t have any.”

Friday night shopping in busy High Street

Friday night shopping in Maitland was amazing, Neville said. “You couldn’t move, the streets were so full. There were eight police on the beat, four on each side of the road making sure there was no mucking up. All the shops were open, even the butchers. Shop employees worked from 8.30am to 5.30pm plus Friday night and Saturday morning until lunchtime. They got paid four pounds a week, if they were lucky.”

“Sale day at the market was always huge. Monday was saleyard day and the area from the Family Hotel opposite the hospital to where the roundabout is today was nothing but saleyards extended to the railway line. The council health inspector, Audley Reay, lived next to the pigyards. People today couldn’t imagine the numbers that turned up on sale days. Auctioneers in full-blast really got into the business and it got fiery at times when there were mistaken bids. The public did a roaring trade in food and drink, and behind the pub all the sulikes and buggies were parked.The stock was brought in by drovers on Sunday along Belmore Road and on Saturday across the bridge along High Street to the pens. North Coast stock and pigs and sheep from the west were unloaded at Telarah and a drover and dog would bring them to the pens.”

“The other big sale day was the produce market. It was known as “the Union” and it was down near the station. Frank Kennedy ran it. It faced Steam Street and ran right back to the railway. Farmers brought their melons, veges, cabbages, caulies, lettuce and whatnot and laid it out to be auctioned. Families would go and buy and then share it out. The food was all local and the growers got paid straightaway. It was always quality and fresh, not like today.”

How the country people lived and worked

“Country people bought boxed stuff, but they made their own butter and cream, and you often got cream back from the farmers when you did deliveries to their properties. One old farmer lived at Largs and every Saturday we got a jar of cream that wouldn’t pour it was so thick, and a basin of homemade butter. He and his wife had six kids and an old Overland tourer with 20-inch wheels and he came to town on Saturdays in a navy blue suit and a white shirt without a collar. The car had high seats and all the kids were on the back except the baby who was in with its mother. The farmers worked from daylight to dark, with a bit of a spell at lunch time. They were well-fed and well-behaved kids.”

“The country people mostly had buggies to get to town. One bloke from Lambs Valley came in every fortnight on a sulky, arrived at 8am and didn’t leave until 4. There was a bridge at Hillsborough, but it got washed away so often they gave up. it was a long way for a horse to travel.”

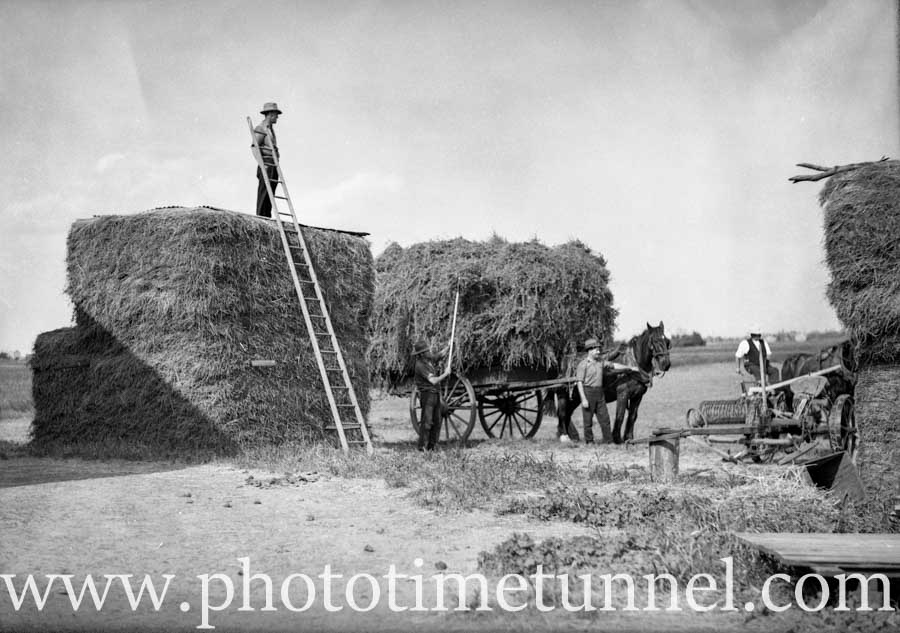

“Of a Saturday my morning job was to go out to one of the farms to help with the hay. Not for pay: just for the interest of it. You’d go to the hayshed, climb the ladder and fork down the hay for the bales they’d sell at the Union. The fowls used to fly up and lay their eggs on the hay, so I’d bring some eggs home. The hay press was operated by a horse who went round in a circle. It was geared to lift the press, then you’d reverse the horse to compress it. They put the battens down, put in hay, press, lift, put more hay in and keep going until full. Then you’d put battens on, wire it up, and cut it in half with a great knife. If you rubbed your hands on the ends of the hay you’d skin yourself. To lift the bales on the truck you had to use a hand winch, they were so heavy. You might put eight bales on a dray to take to the Union to sell. Or next-door was Swan Murray and Hain who would buy a lot of that stuff.”

Neville’s father quit Chant’s in 1933 and became a sales rep, travelling to Grafton, Tamworth, Merriwa, Nelson Bay and Wyong selling flour and – as a sideline – metal paddles for bakers’ ovens.

Win Pender’s Chev-driven air-boat

Among the many well-known people Neville recalls is Win Pender, who lived at Lorn and built himself an air-boat with a Chev engine and an aeroplane propeller in which he’d travel up and down the river. Win was a photographer too, back in the glass plate days. The Penders had timber yards, sawmills and shares in the Turtons tile business. They had nearly the whole block in Elgin Street and bullocks would drag the big logs in, sometimes six feet in diameter, with 20 bullocks to haul.

And Athel D’Ombrain. “I knew Dom pretty well. He was a javelin and discus thrower and he’d practice on Lorn Park. Later he got into fishing. He was always in good shape. Dom was an optician and made glasses. He was very popular and was a good cricketer and writer – a good medium-pace bowler and handy with the bat. He was a very photographer too.

Then there was Rosina Raisbeck – real name Phyllis – whose father was a signwriter with a business in Elgin Street. He painted the writing on bakers’ carts and so forth. Her brother Charlie played a saw like a violin. “Rosina became a diva at Covent Garden,” Neville said. (To learn more about Rosina Raisbeck, click here.)

“I remember Captain Hammond, who flew joyflights in a two-seater plane from Rutherford to Newcastle for five pounds,” Neville said. “He took off from the old racecourse and the plane would shake as it took off over the rough ground. All there was out there was the racecourse and a pavilion. They played polo there, and on race day there was a train with its own siding.”

A lovely piece Greg. He evoked that mysterious period when before we are born, when Plum Jam came in two pound tins from Tasmania and butter was kept at the cafe cool room when it came from Dungog, you can smell the wet hemp of rope and the stink of dead cattle jammed against th bridge in flood. Love oral history, it breathes .

Thanks very much David. 🙂

Re the photograph of cattle in High Street – I didn’t realise there were steam trams in Maitland. Did they operate on the main rail line or on tracks in High Street?

High Gavin, Maitland’s tramway system was very limited, basically linking Maitland, East Maitland and Morpeth. It only used steam and it ran from 1909 to 1926. The Government ignored advice to enhance the system’s viability by extending it to Kurri Kurri etc, and it seems it was never really an economic proposition.