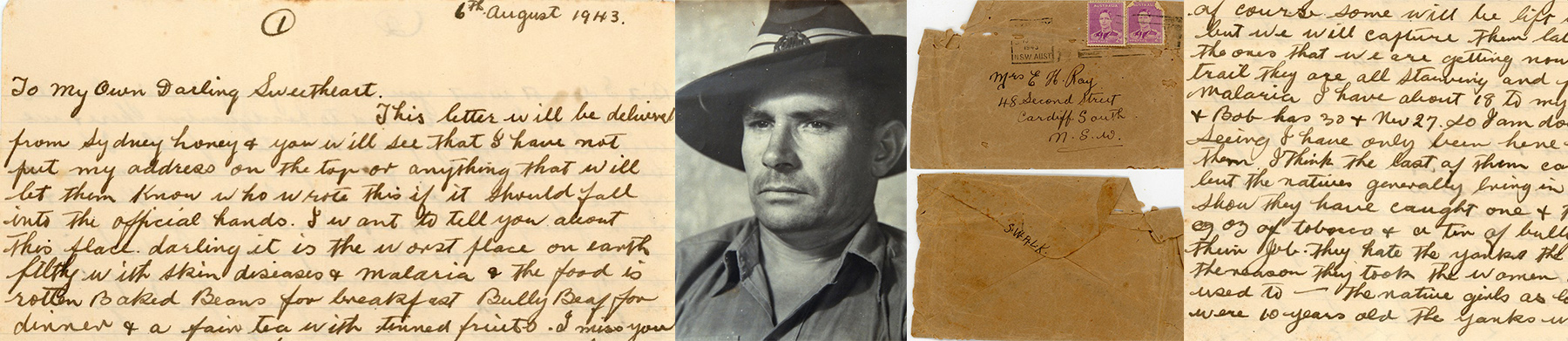

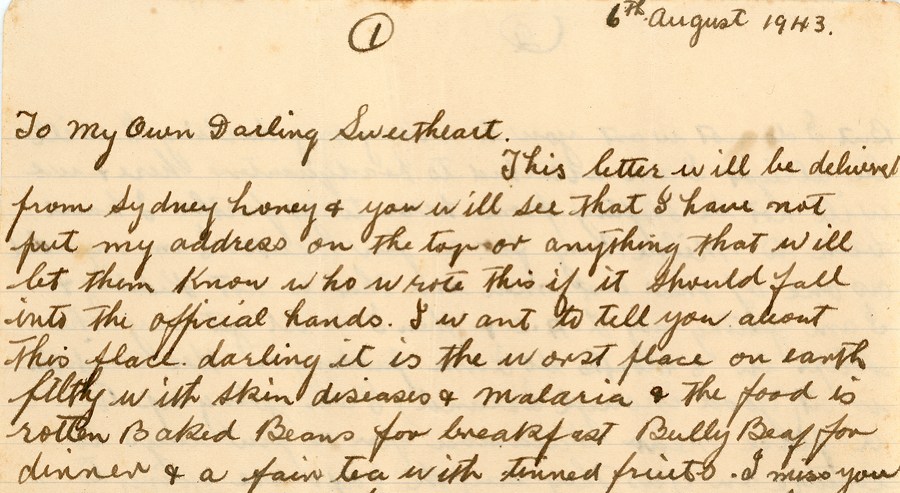

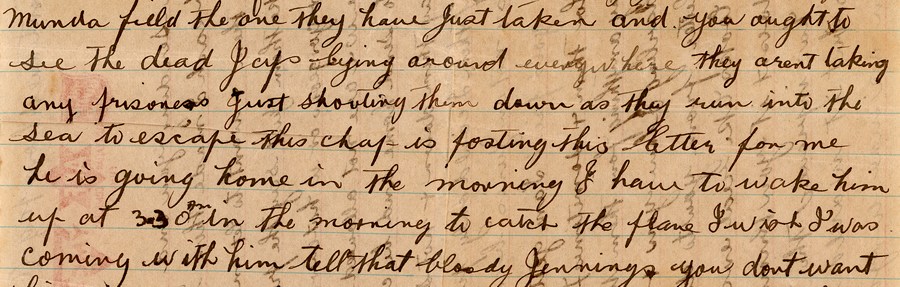

To beat the official censors who read mail sent by Australians serving in New Guinea in World War 2, those servicemen sometimes got their mates going home on leave to carry letters and post them in Australia. It was a simple and effective way to evade the prying eyes of officialdom, whose job it was to make sure that important military details didn’t accidentally fall into enemy hands and that the people at home didn’t hear too much about the grim reality of the war. Accounts I have read by servicemen suggest that mail from home was cherished and anticipated, and the attention of the official censors to private correspondence was not exactly appreciated.

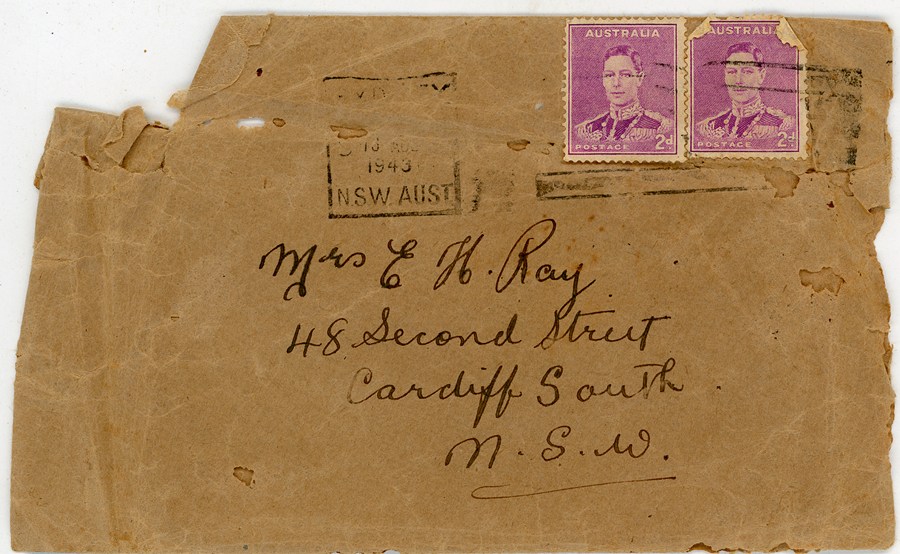

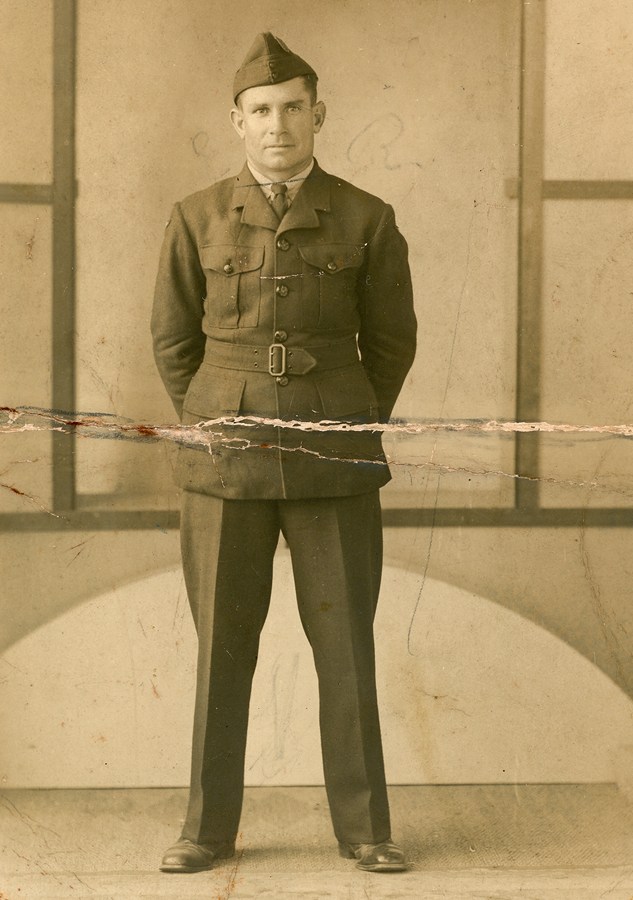

When he went to New Guinea with the RAAF in 1943 my grandfather, Ernie Ray, was already 35. He’d been married to his wife, Hazel, for 13 years. The couple lived at Cardiff South – then a semi-rural suburb of Newcastle, NSW, and Ernie worked in one of the city’s heavy industries.

Hazel and Ern, pre-war

Hazel at her sister’s wedding in 1943

Ern and Hazel’s wedding day, 1931

Ern’s family at home: Brian (left), June and Geoffrey. Hazel at right.

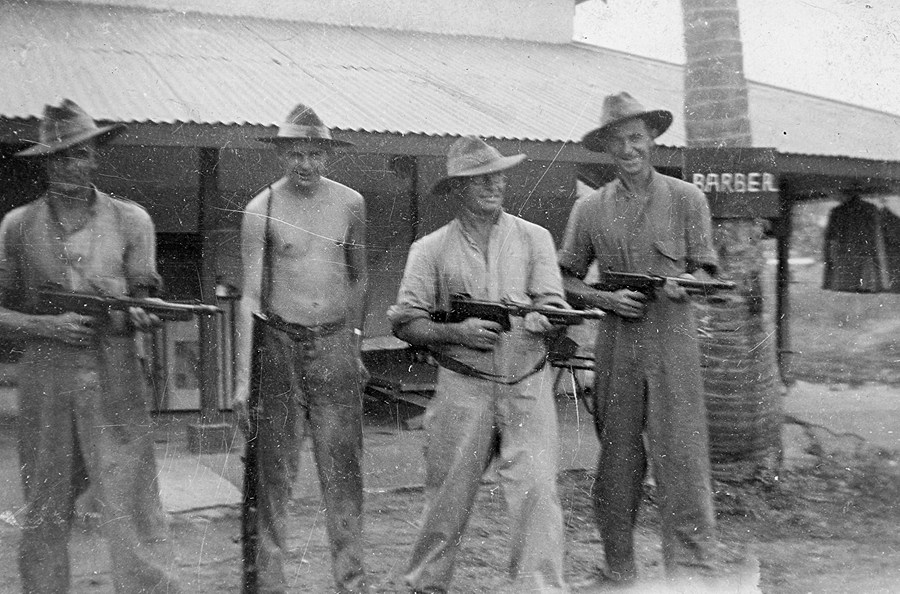

He had joined up in February 1943 and by June that year he was a guard at 45 Operational Base Unit at Port Moresby. It seems his role involved him in guarding Japanese prisoners of war, a fact I have only learned very recently from a letter my aunt dug out from among her possessions in answer to one of my questions. The letter to Hazel was sent via the unofficial channel described above.

It appears to be the only survivor of wartime correspondence between the couple and is a particularly interesting one for a few reasons. First, it shows how servicemen could get around the wartime censors by sending letters home with mates going on leave. Second, it gives me the first glimmer of insight I’ve ever had into my grandfather’s war service. The letter is a very loving one, full of homesickness and affirmations of deep affection that remind me just how much these isolated servicemen lived in fear of receiving a dreaded “Dear John” letter from home. This fear may have been especially pronounced for my grandfather, who had been sent into a boys’ home when his mother and father had separated. Ernie’s father had served overseas during World War 1 in one of the tunneling companies and the marital separation occurred either during or after his service.

In his letter to Hazel, who was stoically raising the couple’s three children alone during her husband’s absence, Ernie is prolific in his expressions of love and affection. He is also anxious to tell his wife something of the poor conditions faced by servicemen in New Guinea. Even though his lot was clearly much easier than that of a typical infantryman in that awful campaign, he had plenty to complain about and much of interest to describe. New Guinea was, he wrote, “the worst place on Earth; filthy with skin diseases and malaria and the food is rotten”. The officers got all the good food, he told her.

The headquarters to which he was attached was being bombed about four nights a week and this was having a big effect on many of the men. “When there is a raid on fellows get down and pray,” he wrote. “Others cry and laugh every time they come over”. He had spent some time in hospital recently when a near miss from a bomb damaged his ears. On the ground, he wrote, the Australians were pushing the Japanese back. “We are capturing Japs every day here and have got to look after the lousy coves . . . The ones were are getting now off the Kokoda Trail they are all starving and filled with malaria. I have about 18 to my credit so far . . . The natives generally bring in a head to show they have caught one and they get one ounce of tobacco and a tin of bully beef for their job.”

“I have been all over New Guinea by plane. I have travelled over 60 hours in the air now. It only took four hours to come over from Townsville and that is a thousand miles so you can imagine how those things travel. We came over in a Fortress and I have been travelling about in big Douglas planes ever since. They are just like a car when they get up, it is beautiful in them. We always have a lot of escort when we go over. Those Thunderbolts and Lightnings they are good kites too. We were attacked by the Zeros last time and our mob shot every one of the Zeros down. It was a wonderful sight. “

“I have a good job at times. We brought 10 Japs back from Goodenough the other day and we landed at Milne Bay on our way back and the cook rushed and said ‘I promised my wife I would shoot a Jap’ and before we knew what was happening he shot one of those Japs on the spot. I don’t know what will happen to him. He was bomb-happy.”

“I have only just returned from Munda Field – the one they have just taken – and you ought to see the dead Japs lying around everywhere. They aren’t taking any prisoners; just shooting them down as they run into the sea to escape. When our mob was making the strip at Milne Bay they ploughed the Japs under the strip. You could smell it a mile off. That was before I got here but you can still smell it of a warm windy night.”

“I am going up to a place near Salamua for a few days to give a lecture on gas. They say the Japs are going to use it in September, but this is a vital secret so it is only for you to know.”

Ernie described in graphic terms the alleged treatment meted out to native women by Japanese soldiers, but he scarcely rated the Americans much better on the basis of their alleged abuse of young native girls. In his letter Ernie described the Americans as: “the filthiest race of people you could ever hear of”.

The letter was deliberately unsigned to help avoid trouble. Hazel was instructed to keep it strictly secret, and to write in her reply that she had read “letter 100”.

Evidently the correspondence between the couple was considerable, and it’s a shame only this one letter appears to have survived. Even though it’s a fragment it’s helpful for re-framing my view of my grandfather, whose life was far from trouble-free, being impacted heavily by two world wars and the Great Depression. He returned to Australia but it seems he was profoundly affected by his war experiences. My father told me that his father never discussed the war: it was an off-limits topic. Ernie’s sole surviving letter gives just a hint of how things were for him during his stint of war service in New Guinea.

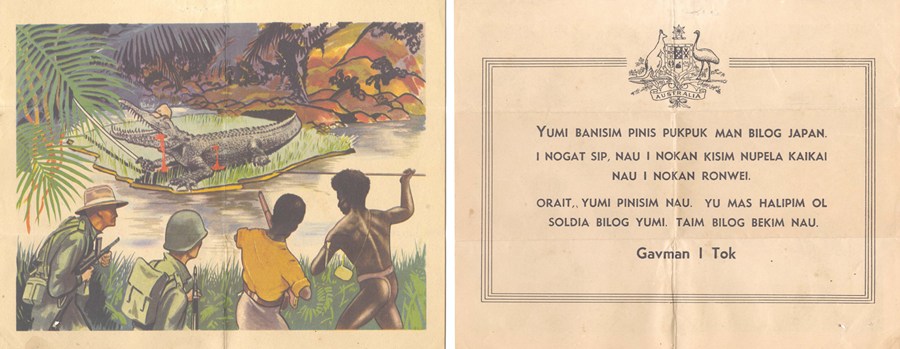

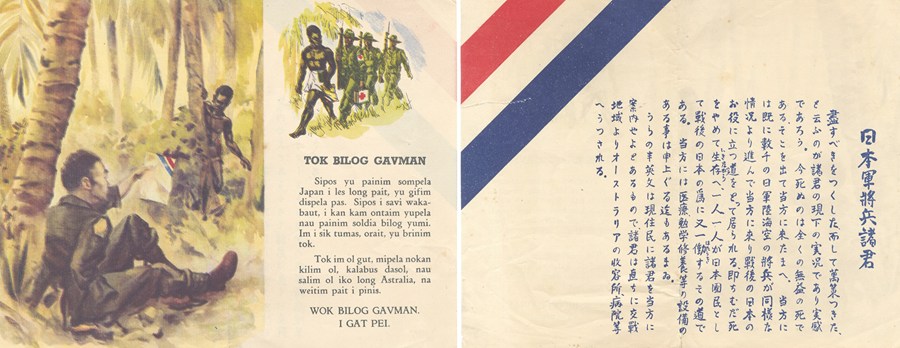

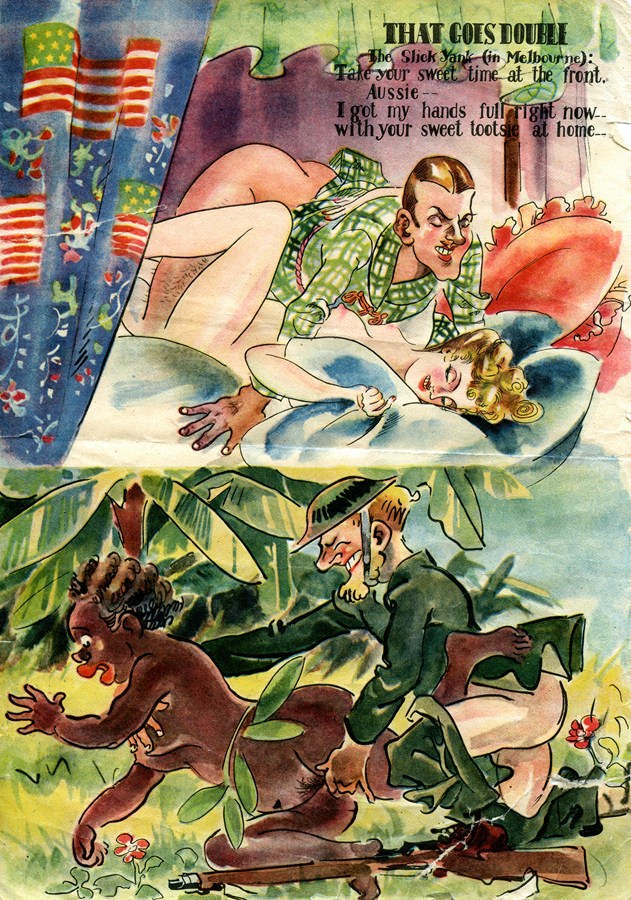

These propaganda sheets are unrelated to Ern’s letter, but give some idea of the ways the opposing sides sought to undermine morale. The Japanese, in particular, knew how much their Aussie enemies feared “Dear John” letters from home, and tried to exploit cracks in the sometimes uneasy alliance between the US and Australian troops.