In December 1973 Newcastle Harbour received a strange visitor in the shape of a balsa wood raft, not unlike the famous Kon-Tiki which Thor Heyerdahl used to cross the Pacific Ocean in the late 1940s.

The raft, named Guayaquil after its point of departure in Ecuador, South America, had struggled across the ocean before its crew was lifted to safety from the apparently sinking raft off Ballina, NSW, HMAS Labuan. Guayaquil did not sink, however. Currents carried it down the east coast where it was found by a fisherman, K. Bollinger, who towed it into Newcastle. For some time Guayaquil was a favoured subject for amateur photographers until it was lifted out of the water and moved to a site behind Throsby No 1 wharf.

The plan had been for Newcastle Maritime Museum to take over ownership of the raft, but then president Capt. K. Hopper said restoration wasn’t practical. There was talk of a model being made from some of the timbers, and some artefacts being retained.

According to press reports, Mr Bollinger had been seeking compensation for his salvage of the raft and this had become a “legal wrangle”. All this came to an end when the raft was destroyed by fire, apparently lit by vandals, on March 12, 1975.

The story of the expedition of which Guayaquil formed a part is told below in this excellent article by David Jones of the Queensland Maritime Museum. I found and saved the article a few years ago in the online boating magazine Bow 2 Stern, but can’t locate it now.

By David Jones, Queensland Maritime Museum, in Bow 2 Stern.

As a young man, Spaniard Vital Alsar was captivated by Thor Heyerdahl’s epic voyage half way across the Pacific in the balsa raft Kon-Tiki. Heyerdahl believed that South American Indians used these rafts to colonise remote Pacific islands. Many thought a single, experimental voyage did not prove this theory, but not Alsar. He believed, and wanted to sail a balsa raft of his own – not just to the Polynesian islands, but right across the Pacific.

Like the Kon-Tiki, Alsar’s raft followed the design of rafts seen cruising the South American coast by the first Spanish explorers in the Pacific. The raft was 14m long and 5.5m wide, comprising seven large balsa logs lashed together by sisal rope and wooden pegs. The logs were specially harvested when sap content was high to maximise their resistance to seepage and maintain buoyancy. No modern materials, such as nails or screws, were used in construction.The raft would reach its destination by riding ocean currents, currents which Alsar believed the ancient Indians knew well. Departing from Guayaquil in Ecuador, Alsar planned first to catch the Humboldt Current off South America, then join the South Equatorial Current which would carry them across the Pacific. The raft would be aided by favourable south-east trade winds caught in a large, square sail. A number of centreboards, called ‘guaras’, lowered between the balsa logs at different positions for’ard or aft, allowed the raft to vary its course across the wind.

A lucky escape

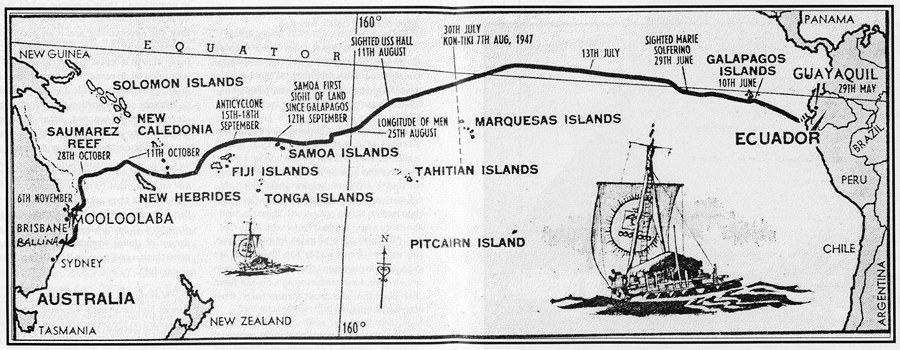

Alsar’s first attempt in 1966 was disappointing. His raft La Pacifica became trapped in doldrums and counter-currents near the Galapagos Islands. It circled aimlessly for months while shipworms ate away at the ropes and timber. After 143 tedious days at sea the raft sank and its crew was lucky to escape alive. Undaunted, Alsar tried again in 1970. His raft, La Balsa, was towed out to sea from Guayaquil on May 29 and was soon moving north with the current. The raft’s four crewmen came from four different countries and three continents, demonstrating international co-operation that was an important theme of Alsar’s voyages. For over five lonely months the raft drifted across the tropical Pacific with its crew eating a monotonous diet of fish.

After passing Fiji they survived a series of storms with waves sweeping over the craft. Coral reefs were a serious concern as they navigated between the New Hebrides and New Caledonia into the Coral Sea. The raft avoided danger until, on October 28, it was driven into Saumarez Reef, 190 miles from the Australian mainland. Anxiously manoeuvring La Balsa as best they could, the crew broke free after jolting on a coral outcrop which broke three guaras and scored the raft’s bottom.

La Balsa’s radio was defective, but next day ham operators heard its signals as the raft approached the coast. At the time Queensland’s air-sea rescue co-ordinator, Captain Whish, dismissed the report as a hoax, saying a balsa raft would have become waterlogged and sunk long ago. Intense speculation continued for several days until a private aircraft sighted La Balsa off Double Island Point just after dawn on November 5. The pleasure launch Capri soon met the raft and towed it into Mooloolaba just before midnight. Despite the hour, a large crowd had gathered to give La Balsa a rousing welcome. Alsar and his crew became heroes overnight. They had completed the longest raft voyage on record, covering 8,565 miles in 161 days. La Balsa was put on display in various Australian capitals before being shipped to Santander, Alsar’s home town in Spain. The raft’s unexpected arrival in Mooloolaba is commemorated by La Balsa Park at Buddina.

Triumph at Mooloolaba

But even a triumph such as this was not enough to satisfy Vital Alsar. He wanted to prove that La Balsa’s success was no fluke. And he wanted to go further – to demonstrate that groups of balsa rafts were capable of long voyages together across vast areas of the Pacific. Accordingly he started planning another expedition using three rafts instead of one. In other respects he would repeat the formula which proved so successful for La Balsa.

The rafts were named Guayaquil and Mooloolaba, for the voyage’s departure and destination ports, and Aztlan for the Mexican city where their 12 crewmen planned the journey. Collectively these three rafts were known simply as Las Balsas. They departed Guayaquil on May 27, 1973 and drifted north-west, joining the South Equatorial Current south of the Galapagos Islands. Soon afterwards the group encountered a severe storm which kept the crews from eating or sleeping for five days. One of the rafts broke part of its mast and lost touch with its companions for almost a week. Fortunately, this was the only occasion during the voyage when any of the rafts were separated.

Las Balsas crawled west along the equator in hot, steamy conditions, with storms, shipworm and a tedious diet of fish trying their endurance. As they approached Australia excitement grew for a festive welcome in Mooloolaba on November 18 or 19. But it was not to be. When only 50 miles from their destination, the currents which had been Las Balsas’ friend for thousands of miles, turned contrary. The rafts were in the grip of the East Australian Current, driving them south. After almost six months at sea the rafts were eroded by shipworm, waterlogged, and too fragile to oppose currents accelerating above 2.5kts. Las Balsas were swept past Mooloolaba without any hope of crossing the stream to reach the shore. Though Australia was tantalisingly close, it seemed they may never land here.

Meanwhile HMAS Labuan sailed from Brisbane and met Las Balsas off Point Danger, taking them in tow. As they approached Ballina the wind and seas increased. Alsar’s raft Guayaquil, barely afloat, threatened to sink in the swell. Her crew was taken aboard Labuan and the raft abandoned. On Wednesday morning, November 21, 1973, the tow was passed to trawlers which brought the two surviving rafts over the Richmond River bar into Ballina Harbour. Once again Alsar and his crew were welcomed by cheering crowds and feted as heroes. They surpassed their 1970 record for the longest voyage in a raft, this time covering 9,000 miles of ocean in 178 days. But more than that, Alsar had demonstrated that ancient Indians could use fleets of these primitive rafts for long ocean voyages.

Two weeks later Guayaquil surprisingly reappeared off Newcastle. She was towed into port, but was subsequently destroyed by vandals. The other two rafts were laid up on the Richmond River, gradually deteriorating in idleness. After several months Ballina Council came to the rescue, salvaging what remained to restore a single raft for preservation. A museum was built to house her and this was opened on the tenth anniversary of Las Balsas’ arrival in Ballina.

Now proudly displayed in original condition, the balsa raft remains the jewel of Ballina Naval and Maritime Museum, located by the river through the town centre. Artefacts from Las Balsas are also on show, along with a wide variety of displays from Ballina’s rich nautical heritage. The museum is a fitting tribute to a historic achievement and a great maritime adventure.

Sources: La Balsa Expedition, published by Ballina Naval & Maritime Museum, 1983.

Alsar, Vital & Lopez, Enrique Hank, La Balsa to Australia, published by Book Club Associates, Sydney, 1974.

The Courier Mail and The Sunday Mail, October & November 1970; November 1973.