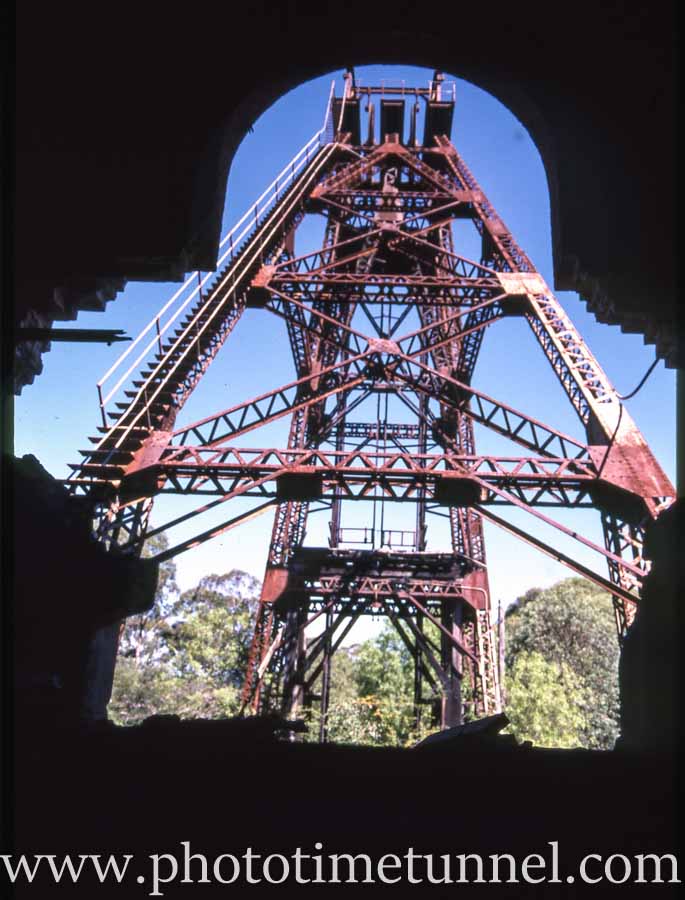

Fred Caban started work at Stanford Main No. 2 mine at Paxton in 1947 when the mine employed 400 men and produced 1000 tonnes of coal a day. One thing he remembers is the great speed at which the steam-powered winding engine could haul a cage up the 400 foot shaft. A cage could carry two tonnes of coal or 12 men to the top of the unloading gantry in 10 seconds. “When the cage dropped away you would swear the bottom had fallen out and you were falling,” Fred recalled. “When going up you had to get a firm grip of the hand-rail. If you failed to do this you could not stand and would end up in a heap on the floor. When the driver cut the steam about three-quarters of the way up it would feel as though you were floating upwards and the coal dust would float up from the floor of the cage and get in your eyes.”

Contract miners worked in pairs and the “darg” was 20 tons of coal a day per pair. They had to bore holes in the coal with a hand drill and shoot the coal out with blasting powder. The powder cost them five shillings for a pound packet, which was as much as they got for filling a ton of coal, so when the coal was easily worked they would dig it out with a pick.

Coal was hauled out to the pit bottom in skips, small wagons that held a ton of coal. These were coupled together in sets of 24 and hauled by 100-horsepower electric winches on thick steel ropes for distances of well over a kilometre. These also had a tail rope to haul the empty skips back in. The main rope dragged along the ground and the tail rope was on rollers suspended from the roof by square steel bars.

One of Fred’s early jobs was to clip wire ropes on and off the sets of “skips”. He would ride the sets to look after them, squatting on the buffers between the second and third skip. The wire ropes, he said, would stretch like rubber as the powerful winding engine took hold.

“If a coupling broke close behind me, the skips I was on would suddenly shoot forward like a shot from a shanghai. If it broke in front of me I would see a ball of fire at the break and the skips would bang together.”

The winding engine caused serious problems at times. Sometimes it failed to stop and continued at full power, with the brakes unable to stop it. “On the first occasion a load of men was ascending and the driver could not stop the cage. The cage continued past the gantry right up to the top of the poppet head.” A safety device prevented tragedy, but the men were left suspended 150 feet above the shaft, with no rope attached to the cage. Another time it was found that the main two-inch rope holding the cage had 13 of its 16 strands broken, forcing the men to leave the mine via the much smaller emergency return air shaft, which could only accommodate six at a time. “It was very slow. In fact you could feel every beat of the engine as we made our way up the shaft in a series of jerks.” The worried miners realised that at this rate it would take hours for them all to escape. The first scare came when the braceman at the shaft-head stepped on a rotten timber and nearly fell down the shaft. The second was when the braceman dropped a steel bar, causing a loud metallic bang, sending the men rushing away from the foot of the shaft in fear. Next there was a “tremendous rumbling and roaring of something falling down the shaft.” A guide rope near the top had broken and fallen, scattering the frightened miners yet again. “When we all settled down I heard one fellow say: ‘I think somebody shat in my trousers!’. We all eventually got out safe and sound.”

Fred said he developed a “sixth sense” while working underground. “When the skips banged together which would surely have smashed my hips, I would be off an instant before it happened,” he said. “The same thing used to happen with roof falls and the many other dangers that happened in the pit. When I was 17 I revelled in these near misses and if I didn’t narrowly miss out getting killed or injured about twice a week it was getting too tame for me. But by the time I got to 20 I thought I could do without them. On one occasion I walked into a winch room in the north section. The winch driver was leaning over the winch with an oil-can while it was running at full power. Ned’s trousers got caught in the gears. I got there just in time to throw the winch into reverse and jump on the brake. Had I not been competent with the winch Ned would surely have been dragged through the gears with very tragic consequences. I might add I would have been younger than 17 at this time.”

According to Fred the miners were tough men, but loyal mates. “It was said that the miners filled all their coal in the pub, drank their beer in their home and had all their sex in the pit because that was 90 per cent of their conversation.”

From our book, The Way We Worked.