DOG wallopers and woolly tigers were commonplace in Doug Bowman’s Newcastle. Doug was 95 when I interviewed him in 2013, and it took him a while to get warmed up. But once he got started, the stories came thick and fast. Doug was one of those men who could talk his listeners back to the Newcastle of his youth, where they could see and hear with him strange sights and sounds of another city and another time.

Doug’s grandfather, Thomas Mather Bowman, was ‘‘factotum’’ for the mighty Australian Agricultural (AA) Company that controlled some of the finest money-making assets in the colony of New South Wales. He was, in other words, a security man and a supervisor of cleaners who lived in one of several company cottages down on Wharf Road, near the company headquarters of Argyle House, later to be Fannys nightclub. Raised with the stories of the great old company, Doug had an affection for a house of commerce that was, in his eyes, as fair as it was tough.

Stopped the dogs from peeing on the walls

He talked about the company’s Sea Pit, with its entrance near modern-day Nesca Park. The side of the hill was a paddock where the pit ponies had their stables and their recreation. ‘‘The men worked the seam three or four miles out to sea until the floor got too damp and they wanted danger money,’’ Doug said. ‘‘They reckoned they could hear the vibrations of the steamers passing over their heads while they worked under the ocean floor.’’

Doug’s father’s first job was a trainee salesman at Winns department store, but at first his duties were dog walloping. ‘‘He had a cane with a whip-end and a piece of lead on it, and his job was to walk around the footpaths chasing away the dogs before they could urinate on the windows. It was 10 hours a day for five shillings a week,’’ Doug said.

Doug earned his first income from the AA company: 10 pounds a year for taking messages every night, from 5pm to 8.30am, from the company’s far-flung rural stations. ‘‘They had to report all the stock movements by telegram at night,’’ he said. One of Doug’s early jobs, when he was aged between 15 and 18, was managing the AA Company’s Tingha property. It toughened him up so much that, when he came home, his mother refused to let him go back. He worked as a carpenter and joiner, served in the armed forces in army intelligence during World War II (including liaison work with US forces in Papua New Guinea) and then spent decades as a commercial traveller.

As a youngster Doug always felt a special link to Newcastle’s busy harbour. His mother’s father was an engineer on the water police launch: an accomplished “mortar man” whose job with the rocket brigade was to fire the rescue line over ships in trouble. The water police also had to inspect dairies and private slaughterhouses as far up-river as Raymond Terrace, not to mention breaking up scores of waterfront fights in the rough and ready days.

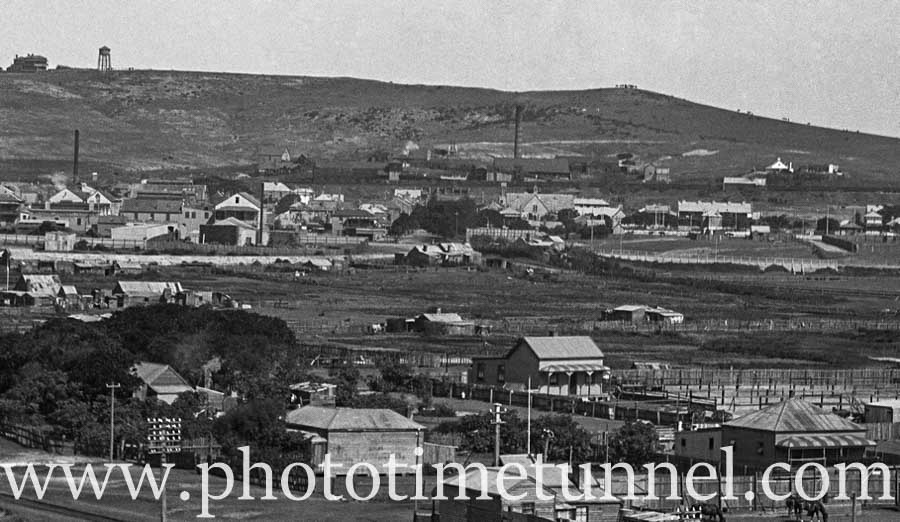

Not far from the foot of Merewether Street, he recalled, was a great mound of dried spoil, dredged from the bottom of the harbour. Behind that hill rival gangs of wharfies – union and non-union – would have savage stone fights. Doug recalls the odd little boat harbour that once adjoined the city’s markets and was home to the boatmen who competed with one another to supply visiting ships. “With six oars and one to steer, they could fly through the water. It was nothing for them to row as far as Terrigal to be first to get a ship’s order, and they’d often beat it back to harbour. They didn’t have to tack like a sailing ship.”

Perched on the edge of the boat harbour was Hartley Spurr’s strange little bait store. “He was already an old man when I met him,” Doug said. “He used to give me fish hooks and we’d all fish on the harbour’s edge when we got the chance. I’ll never forget his dirty old apron and gumboots, and the smell of prawns in his shop, that never seemed to close.”

Fun at the steamer wharf

Doug’s family lived opposite the intercity steamer wharf, a place of endless fascination. “There was always interesting gear lying about: rolls of cabin bedding and the food preparation gear being brought off for cleaning before going back again,” he said. At night the proximity to the wharf was less congenial, with the noisy 2am booming of empty fuel drums crashing onto the wharf from the decks of the Malinga and the Nimbin.

With no Stockton Bridge, the punt across the harbour did a roaring trade. In holiday times the queue of vehicles stretched a long way back along Wharf Road.

On weekends a couple of old ex-Sydney ferries worked the picnic trade, taking groups of employees from various shops and factories – and their families – on excursions up-river. “They could only do about seven or eight knots, and on board they had music, ice cream, ginger beer, lemonade and boiled lollies,” he said. “As they started across the harbour it seemed they were headed out to sea, and the swell used to hit them and make everybody seasick before they turned back upstream. At the end of a picnic all the children who’d started out in the morning in their Sunday best would be a mess. Dirty, grimy, full of lollies and ice cream, but happy and tired.”

One of Doug’s most memorable journeys was to Sydney on the steamer Hunter for the celebrations surrounding the opening of Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. “It was two-and-six special price and a group of us brats went down. The oldest was 13 and the youngest was nine,” he said. “We were on the foredeck, over where we should have been sleeping, but we stayed awake counting the electric lights on shore. The trip took from about midnight to 6am and at first light we fell in with a pilot boat and we stayed with her as we entered harbour, as if we had our own escort.” The carnival was spectacular, even considering the depression conditions. “They put us ashore and we walked to the celebrations. They filled us up with toffee apples, ice cream and ginger beer and by the time they took us back on a truck at the end of the day we were wrecked. I fell asleep at 6.30pm and didn’t remember another thing until we tied up at Newcastle again next morning.”

Doug’s mother worked as a legal clerk in Bolton Street, and when she finished work she’d walk home, sticking to the middle of the road when she reached Darby Street, on account of the concentration of drunks in an area rich with pubs and rum-shops. In one of the pubs was a violinist named Fred, a great character who befriended the wives and matrons of tough Cooks Hill. “The women brought garden vegies to the pub and got fourpenny darks – brown muscat. Fred gave them two free ones on their birthdays,” he said.

“And if anybody had a hangover, Fred would give them a woolly tiger. What’s a woolly tiger? Oh, that’s a raw egg in a glass of beer. It settled your tummy like nothing else.”