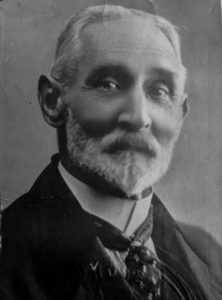

Captain Donald MacRae, former harbour master of the Port of Newcastle, Australia, was credited in some quarters with being the last Allied serviceman to be evacuated after the failed British invasion attempt at Gallipoli, Turkey, in World War 1.

His long career was punctuated by acts of great bravery. He died and was cremated in 1963 and his ashes remained among the possessions of his son-in-law until 2015, when some of his grandchildren scattered them off Big Ben Reef, Newcastle, the scene of one of his famous rescues. In 2023 those grandchildren fixed a plaque at the end of Newcastle’s Nobbys Breakwater, commemorating his eventful life.

Donald MacRae was born in Scotland in 1892 and went to sea in his teens. According to documents still in the hands of his family, he began his seafaring career in the twilight years of sail. In 1910 he was an ordinary seaman on the sailing ship Loch Katrine, making two voyages to Australia aboard her, including one in which the ship was dismasted in a storm in late April about 500 km off Green Cape – southern NSW. The ship’s lifeboat was picked up by the Swedish steamer Tasmanic.

He switched to steamships after that, and was rated as an able seaman later the same year, continuing to serve on ships on the colonial service between the British Isles and distant Australia and New Zealand.

He left the merchant service and joined the Royal Naval Reserve in the early stages of World War 1, finding his way to Alexandria, Egypt, where he was seconded to work as naval liaison with the customs service, preventing enemy cargoes from evading British trade sanctions. According to a report on his duties, one of his main roles was to neutralise enemy spies who used small sailing craft to carry information to other ports and to German submarines. Temporarily promoted to the rank of Lieutenant, MacRae was praised for the “tact and ability and perseverance” that enabled him to obtain “four convictions against enemy agents”. He was recommended for a decoration on the strength of his efforts, but this does not appear to have been acted on.

MacRae was for some time in command of the auxiliary transport vessel, HMT Blossom (a hired fishing drifter), as well as having charge of the harbour examination vessel Alexandria.

It seems he was employed in these roles when the British decided to evacuate Gallipoli at the end of 1915 and according to some postwar soldier accounts published in The Bulletin, he was “the last man off the beach”.

One soldier wrote contesting the claim by General J.O. Paton to have been last man off, insisting that “the honour belongs to a long thin naval officer known as ‘Smiling Mac’ . . . The last soldiers to leave were the Indian RA from Chocolate Hills and the officers and men who blew up Russell’s Top. These men were guided from the trench to the beach by the officer in question and embarked on the last lighter which left Milo’s Pier. Smiling Mac then boarded a waiting naval launch with a machine gun on his shoulder, insisting on taking his curio with him. General Johnson, RA, NZ Division, was on the destroyer which took the launch’s occupants to Mudros, He heard about the gun and took charge of it. I was one of the several who saw the General note the officer’s name and nobody on board had any doubt about his being the last man to leave Anzac”.

Other witnesses agreed, confirmed the story of the machine gun, noted that “Smiling Mac” was named MacRae and was by that time living and working in Newcastle, NSW.

MacRae’s efforts to get “his” machine gun back from General Johnston were unsuccessful, as a letter he preserved, signed by a member of the general’s staff, attests. The letter, dated April 4, 1916, wishes him luck but doubts his chances of success.

While he was working for the Naval Reserve in Alexandria during the war, Donald MacRae met his future wife, nurse Mary Fletcher, a member of the Queen Alexandra Nurses. Mary, born in 1891, had trained at the Leeds Township Infirmary from 1912 to 1915 and in 1915 she was posted to Mudros – near Gallipoli – and she also served in Egypt and Palestine. Donald and Mary’s old wartime photo albums contain pictures of the pair enjoying picnics and other outings during their time off-duty. They married in Sheffield, England, on June 2, 1919.

MacRae was invalided out of the naval reserve in November 1919 (the documents don’t record why) and at some point he came to be employed in the pilot service at the port of Newcastle, NSW. He served as captain of the Ajax, the last steam-powered pilot vessel at Newcastle and served on its replacement, the Birubi. He became harbour master in Newcastle from 1944 to 1952 before taking the corresponding role in the Port of Sydney.

Among the highlights of his distinguished career at Newcastle was the remarkable rescue of the crew of the yacht San Pan in April 1936. The San Pan, with two brothers named Jones aboard, was a Sydney yacht visiting for Lake Macquarie’s annual Easter sailing event. Along with two other yachts, Kestrel and Rondon, the San Pan struggled across the bar at Swansea but was hit by a strong gale and forced north. San Pan hugged the coast and tried to enter Newcastle Harbour late at night but struck on Big Ben Reef – just outside the harbour entrance. The Jones brothers got out of the wreck onto the rocks of the reef, where their situation was desperate.

The Birubi, under Captain Scott Olsen, left the harbour and used its searchlight to spot the wreck, but all aboard agreed at first that the chance of a rescue was too remote to risk in the heavy seas and gale. MacRae, on board as pilot on duty that night, later wrote an account of what happened next. He wrote that he reconsidered the situation, feeling unhappy about leaving the two stranded yachtsmen to drown. He changed into old clothes and asked for volunteers to join him in one of Birubi’s boats for a dangerous rescue attempt. Four men volunteered. They were coxswain Ratcliffe and seamen Bowen, Masson and Rutherford. In volunteering, they were all well aware that they were taking a huge risk with their own lives.

It must be said that, in his written accounts of his various exploits, Donald MacRae was not one to minimise his own role, nor did he hesitate to criticise others. In his account of the San Pan rescue he wrote that he believed a channel existed through the rocks where the rescue boat might be guided. According to his account: “When we got to where I thought the channel was we could see nothing but broken water. I then addressed Seaman Bowen, who was stroke oarsman. ‘Here you bloody little water rat, you were born here, you ought to know where this channel is.’ He said ‘Yes’. ‘Well give me your oar and guide us in’. He replied ‘Oh, no! You keep charge and guide us in’. I immediately realised that they might lose confidence in me and said, ‘Stick to her boys. I have been in tighter corners than this before and will get you out of this safely’. I took the chance and said, ‘Lay to it boys’.”

They got through the channel, but couldn’t see the yacht or men until the Birubi flashed its searchlight. Working the boat to about 10m from the stranded men, they called them to swim for it and, dragging them into the boat, had them lie down in the bow and the stern. Afraid to try to take the boat ashore, they battled back to the Birubi and got on board at about 11.20pm.

Meanwhile the yacht Kestrel was also in trouble. It had tried to enter Newcastle but a strong ebb tide swept to out to sea, their jib blew out and their engine started giving trouble. The Birubi had to go out again to tow the yacht to safety.

Next morning police officers, investigating a strange object in the harbour near the Stockton shore, discovered that the battered San Pan had drifted in during the night. It was taken to Wickham for possible repair.

This extraordinary rescue was certainly one of Donald MacRae’s career highlights, but there were others.

On August 12, 1943, during the height of World War 2 and with Japanese submarines causing fear to ships’ crews, MacRae was commended for his role in saving the armed cargo ship Kotor and its contents after the ship careered into Newcastle’s northern breakwater. In a report to authorities MacRae noted that the collision seemed suspicious. The Kotor had grounded when leaving Adelaide not long before. The incident was blamed on faulty steering gear, but no reason for the fault had been found. In Newcastle the grounding was again blamed on a jammed steering engine, but MacRae found this suspicious, based on his own observations. There was also an apparent delay in dropping anchors at the request of the pilot who was helping take the ship to sea. Since the Kotor was fouling the fairway it had to be moved, but moving it risked setting off some of the mines that had been laid in the area. MacRae had it moved, under tow, and was commended for his skill.

On October 4, 1943, an American wooden cargo ship, the Davenport, was tied up for repairs alongside one of the berths at The Dyke when a fire started in the engine boiler room and quickly spread. The ship, loaded with fuel oil and ammunition, was regarded as a time bomb and firefighters worked furiously to stem the flames. At least some of the ammunition aboard was rapidly unloaded and put on the wharf, but as it became apparent the ship was doomed and it might explode and damage wharf facilities, a decision was made to tow it out of harm’s way. Two firefighters were hurt by an explosion on the ship, and volunteers were needed for the dangerous tow.

Donald MacRae, at that time the assistant harbour master, joined the Davenport’s skipper Carl Hubner and two of his crew, Keith Oliver and Victor Carlsen, to undertake the risky job. The tug Champion took the tow, and the tug Apollo was lashed alongside before deciding to move away. According to Captain Hubner’s report, “several explosions took place proceeding down the channel”.

“By the time the vessel was anchored at about 7.30pm she was alight fore and aft and it was necessary for myself and the two men to jump into the sea in order to make the launch for transfer to the pilot vessel Birubi. Vessel burned all night at the anchorage and finally sank about 11.30 am leaving several oil tanks on the surface,” Captain Hubner wrote.

“I would like to record my appreciation of the services of all concerned in the disaster, especially those of Captain MacRae and the two men, Keith Oliver and Victor Carlsen, who accompanied me to sea in the vessel which involved great risk. Their action no doubt saved damage to the port facilities.”

Donald MacRae’s report criticised the Apollo for letting go and refusing to come back, but noted that “while on the way out several explosions occurred throwing burning timber overboard into the harbour and when rounding the northern breakwater the munitions exploded, blowing the derricks and portion of the after-structure over the side. When well inside the northern breakwater in Stockton Bight we let go the tug and also let go both anchors. With the choppy sea, heat and flying debris from the explosions, launchman W. Scott had great difficulty in getting close to the ship. The master informed me that he could not swim. The other two men could swim so we arranged to assist him should we have to jump overboard when the oil tanks blew up. I ordered the two sailors to get down the ladder which was hanging over the starboard bow. They both fell into the water but managed to hang onto a line which was thrown over from the bow, The master then tried to get down to the launch and he also fell into the water. I followed and managed to make the launch and caught hold of the master. One of the men managed to get on board and assisted to lift the master inboard. We then got the third man aboard and got away as quickly as possible from the ship before the two main oil tanks which were carried on deck and had for some time been enveloped in flame exploded. We then boarded the PS Birubi from the launch Hunter”.

MacRae was understandably grateful to launchman Scott, who brought his little vessel into Stockton Bight in the dark “and managed to come alongside the Davenport though covered with sparks from the various explosions, flying debris and through great heat and brought us back to the PS Birubi”.

Donald and Mary had three children: Duncan, who was killed in a flying accident while serving with the RAF in World War 2, Donald Jnr, who served with the Australian Army in New Guinea, and Margaret.

Mary MacRae worked as a nurse in Newcastle and died in 1951, a year before Donald, after 19 years as Newcastle Harbour Master, moved to Sydney. While in that role he achieved a piece of fleeting fame when he ‘‘booked’’ the royal tour ship, Gothic, for speeding on Sydney Harbour. He had ordered the ship’s pilot to travel at eight knots but it sped up to 10, prompting his reprimand.

Their grandson, David McKinlay, along with two other grandchildren, Mary Anne MacRae and Mary Downey, were taken as guests aboard a Newcastle pilot vessel in 2015 to scatter Donald’s ashes off Big Ben Reef. It had been a shock, they said, to find his ashes and they made a heartfelt decision to pay tribute in a way they believed he would have appreciated.

This year they followed up that gesture with a memorial plaque at the end of Nobbys Breakwater, not far from scene of the San Pan rescue.

Thanks to David McKinlay for the source material used in compiling this post.