There was a time when it seemed as though no contentious conservation or heritage issue could arise in Newcastle, NSW, without the opinions of Doug Lithgow being sought and quoted. Never self-interested or egotistical, Doug was (and still is) the epitome of a generation of modest, hard-working community-minded idealists.

Born in Gladesville, Sydney, in 1933, Doug loved the area around Gladesville; sailing on the Parramatta and Lane Cove Rivers with the Warrego Naval Training Group. He spent some of his early years with family at Gilgandra, under the shadow of the Warrumbungle Mountains.

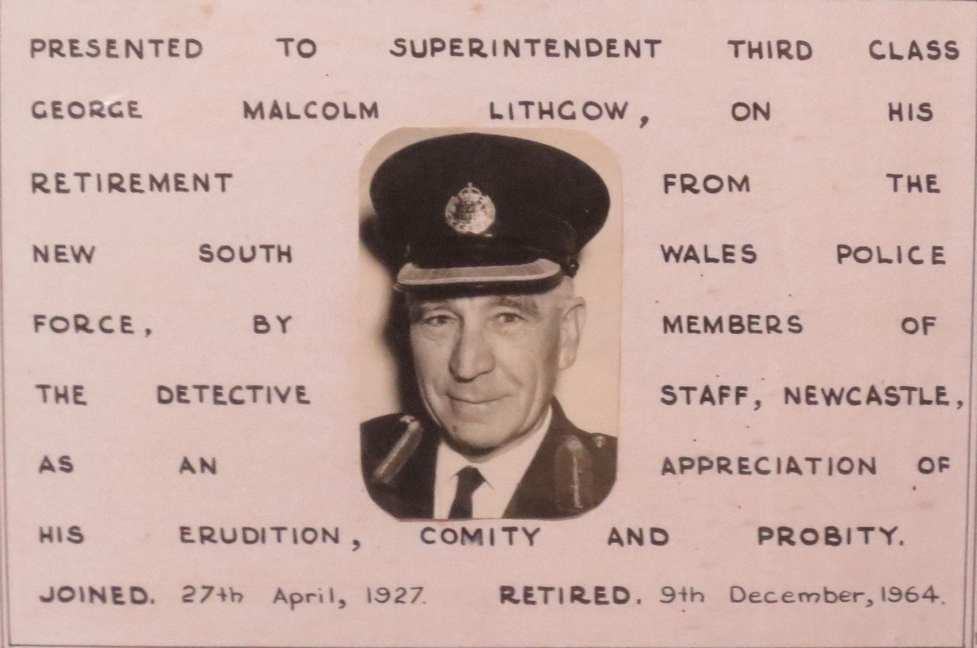

His police officer father was transferred to Wagga Wagga in 1947 and although Doug liked the town he didn’t take to school there and he left at 15 for an apprenticeship with E.W. West and Sons “reboring motors, re-metalling connecting rods, putting in bushes and gudgeon pins and regrinding crankshafts”.

Doug’s father’s next transfer was to Newcastle in 1951, and Doug moved up too, continuing his apprenticeship and learning toolmaking with the big engineering firm Goninan. At that time all 18-year-old males were required to do military training, but Doug’s was deferred until his apprenticeship was completed in 1954. When the time came he went into camp at Holdsworthy with the 19th Battalion, as a sapper. “It was my introduction to the big wide world,” Doug said. He went into the 14th Field Squadron at Newcastle, doing bivouacs at Singleton and Nelson Bay.

Around that time the Crown Lands Department was breaking up big land holdings and creating subdivisions near Bagnalls Beach and Dutchmans Beach, Port Stephens, and his father was successful in a draw for access to one of the blocks. Initially he paid rent, and when the opportunity arose to buy the block he did so.

Industries didn’t modernise

After his stint at Goninan Doug worked for a couple of years at Newcastle State Dockyard. “They used to build amazing stuff there. Polar engines, triple-expansion steam engines . . . ,” he said. ” But Newcastle always suffered from the fact that the industries here didn’t modernise progressively. Everything was always left until the whole thing fell in a heap. We used to build so much stuff in Australia. We had all the gear and the right trained people, but our equipment wasn’t modern. At Goninan and Comsteel they had big machines that came from Germany as reparations after World War I.”

Doug was doing lots of courses with the WEA (Workers Education Association). “It was a fantastic thing in those days,” he said. “They had really interesting people giving lectures on every imaginable topic, from ancient history to geology and economics.” Having done his Leaving Certificate at night at Hamilton Technical College, Doug became aware that the Department of Education was looking for people with trades experience to become industrial arts teachers and he decided to make the career shift. For two years he lived on his savings, studying at Newcastle Teachers College.

Doug’s first country teaching placement was Nelson Bay, which was a stroke of good luck. His family had moved back to Wagga Wagga, but the property his father had bought at the Bay was still available for Doug to use. By now he was becoming deeply interested in conservation and he became involved with a push to create a national park – even though the concept of national parks as they were later to be developed didn’t really exist in Australia at the time. Many weekends were spent walking in the bush around the Bay and exploring the Myall Lakes. It was on one of these Myall Lakes excursions that Doug met his first wife, Marilyn, with whom he was to have two children. [In 1970 Doug’s wife Marilyn died. About a year later he married again and he and his second wife, Mary, had another two children.]

Northern Parks and Playgrounds

At a certain point Doug became aware of the Northern Parks and Playgrounds Movement – the organisation that, in time, his own name would become synonymous with. “While I was trying to get a state park at Nelson Bay I met up with Joe Richley, who used to have his meetings in a little committee room at Newcastle City Hall. I got involved with the movement when they were trying to negotiate with the Housing Commission, which was wanting to build flats at Dixon Park on part of the old Merewether Estate. Eventually we got agreement from the trustees of the estate and from Northumberland County Council to have a little bit of extra land dedicated as a park,” he said.

The main figures in the parks and playgrounds movement were Joe Richley, Rod Earp and Tom Farrell, with barrister Basil Helmore helping a lot with the Dixon Park campaign.

Doug taught woodwork, metal work, tech drawing and art at high schools, notably Cardiff, and he cultivated a close relationship with Newcastle Art Gallery that led to artworks being loaned to schools.

Among the many campaigns that Doug recalls is the fight to keep a proposed expressway out of Blackbutt Reserve. “We weren’t happy with expressways,” he said. “We felt it should have been kept out of urban areas, which should be serviced by local roads and public transport. We wanted the expressway kept out west of the city, with links inward. Finally the government did develop that idea and it took a lot of traffic out of Newcastle. You can thank Transport Minister Peter Morris for that.”

Doug was involved in a heated campaign to save a line of fig trees at Wickham from the axes of Newcastle City Council. It was this campaign that brought Joy Cummings – later to become the first female Lord Mayor of Newcastle – into active council politics. “In those days the councils didn’t have all the tree-lopping equipment they have now. Workers had to climb up high to lop trees so the council didn’t like letting trees get tall,” he said. Despite the fight some of the trees were removed.

Cathedral Park trade-off

He recalls the circumstances surrounding the transfer of the old cemetery at Christ Church Cathedral to Newcastle City Council. “What culminated in the Christ Church Cathedral Cemetery Act of 1966 really started with the idea of the King Street parking station,” Doug said. “The most senior planners were against that idea because that area was supposed to be a park as part of the focus of the city marketplace. But the city council worked out a plan to take the cathedral cemetery as a park instead, to compensate, so the parking station could go ahead. Incidentally two beautiful big old candlewood trees were destroyed too. It was outrageous, really. And in amongst all of this the Newcastle Club got a new carpark that took out part of the old cemetery,” he said.

These days few people recall the existence of the Northumberland County Council, which was set up as the over-arching planning body for the Newcastle area. “After World War II there was great interest in planning, and the Cumberland County Council was set up in 1946 to look after planning in Sydney,” Doug said. “In 1948 they created the Northumberland County Council to do the same for Newcastle, with Frank Stone as the first planner. I knew Frank very well but disagreed with him on a lot of things. He was a ‘flat earth man’, who could see straight lines on a map but Newcastle is very hilly. He wanted major parkland areas cut through with roads bringing cars to the city centre. But they found out with Canberra that it doesn’t work with cars. If you bring them all to the centre they destroy the centre. Cars have destroyed city centres everywhere.”

Northumberland Plan

“I liked the machinery of the Northumberland plan, but it never got revised. The Northumberland Council had the planning power and the professional people and it could have produced remarkable results. But there were so many people with contradictory ideas and interests. The county council was trying to consult wideky but it was very hard to carve through. In 1952 the first plan went on exhibition but there were many objections and it was very slow. In 1957 the plan was on exhibition all year. The county council was getting ready for a new planning cycle but it never happened.

“Northumberland County Council was abolished because of all the arguments from local councils. In 1960 the Government wiped it all and said: ‘right, there’s the plan’. Councils got their planning powers back and the state was only to look at the state-significant things. This got legislated into the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, which has been fiddled with.”

Doug was a great supporter of Lord Mayor Joy Cummings and her vision for Newcastle’s Foreshore Park. “Joy was an important person for Newcastle. She was educated and she had a sense for the landscape. The Foreshore and the international competition for a design was a great civic idea that worked out because the Commonwealth put some money in,” he said. “The tragedy was that Joy had a stroke and then Labor tried to keep her going. It was a sad time. Don Geddes was running the opposition on the council and the Government sacked the council to stop him becoming Lord Mayor. It was a misuse of political power but we are used to that now because it’s normal.”

Asked for his views on planning in Newcastle in 2020 Doug said, not surprisingly, that he believes the system is heavily weighted in favour of the private development industry. “I feel as though ordinary people have been cut out. Most things are there to develop business. That’s the way it’s gone. I’d still like to see some of the major, nationally significant heritage sites in Newcastle gazetted and recognised in some way, like the Civil War sites in the United States are recognised. I still dream of an East End Historic Site, showcasing our convict, Aboriginal and industrial heritage.”