Doug Lithgow, Freeman of the City of Newcastle, NSW, and noted campaigner for the environment and heritage, can cite many high points in his long life of activism and community involvement. But one of which he is especially proud is his “discovery” of the original hand-drawn map of the mouth of the Hunter River, drawn in 1797 by Lt John Shortland, RN. Actually, the chart wasn’t lost. Like much of Newcastle’s documentary heritage it was simply kept somewhere other than Newcastle. In this case, the somewhere else was the Hydrographic Office of the British Royal Navy at Taunton, Somerset.

Doug visited Taunton in 2008, spending a day-and-a-half doing his best to locate maps and charts of interest to Newcastle and the Hunter Region.

Doug said he had been urged by his brother-in-law, a commodore in the Royal Navy, to write some letters seeking access, noting that the navy had kept extraordinarily comprehensive records of the world’s ports and harbours over a very long period.

Like the CIA, but with slower communications

“All captains were required to bring maps, charts and information about foreign ports to the Admiralty,” Doug said. “It was a boon to British commerce. The Admiralty was like the CIA in some respects, but with much slower communications.”

Doug said he was often saddened to discover how much of Newcastle’s history was stored in other parts of the world. “I would never have been able to get access on my own, so luckily Gionni Di Gravio from the University of Newcastle Archives smoothed the way for me. Even then, for the time I was there I had to be accompanied at all times by a naval officer.”

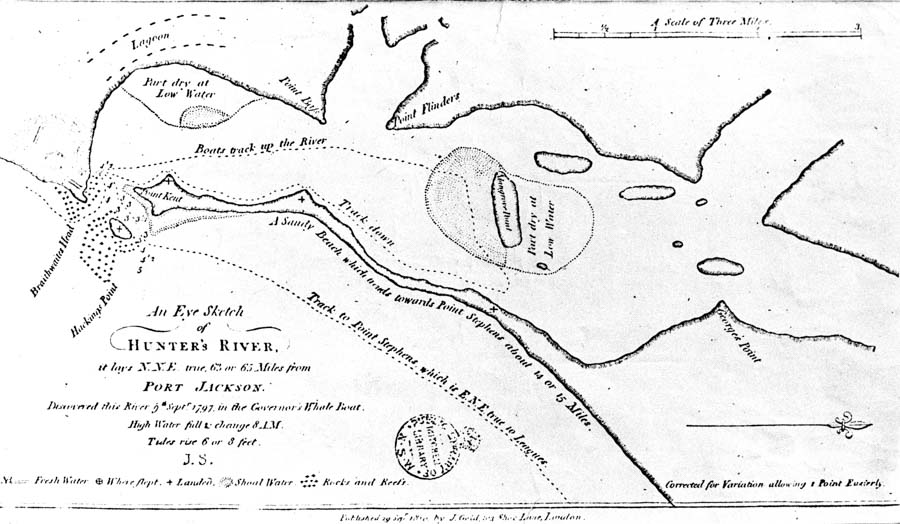

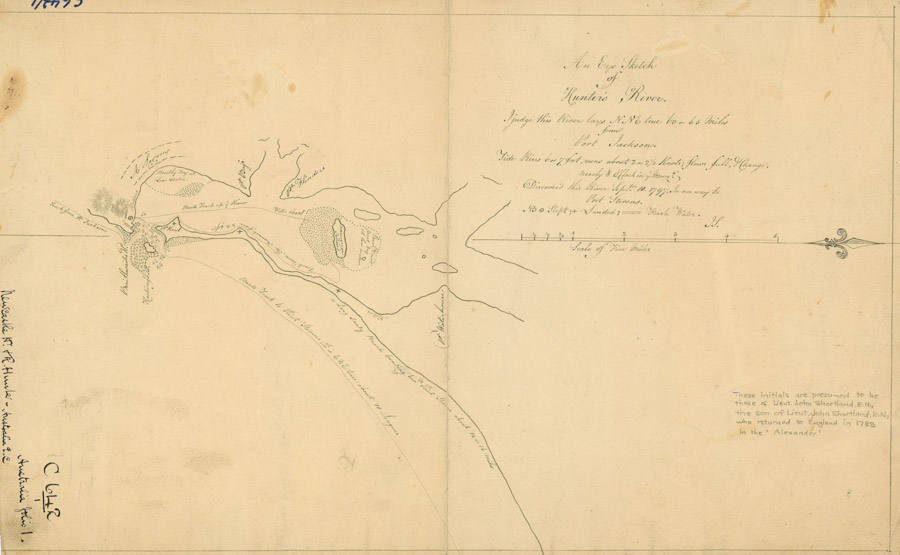

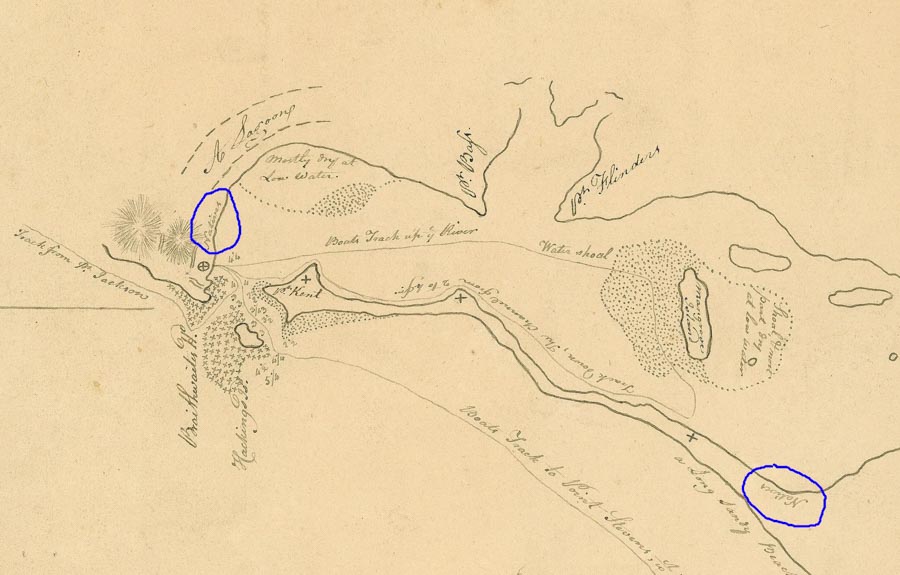

During his visit he saw many charts, but the greatest success was being able to view the original sketch-map of Newcastle Harbour drawn by Lieutenant John Shortland in 1797. It was Shortland’s observation of the presence of coal that later led to the foundation of the European prison settlement known by turns as Coal River, King Town and Newcastle.

.

.

“This really excited me because it showed a native presence on both sides of the harbour. In the later, printed version of the map, made in about 1810, the reference to the natives was erased, and that was the map that everybody was used to seeing. I’ve been fighting against that image ever since,” he said. You can read Doug’s report on his visit to Taunton here, at Newcastle University’s superb Living Histories website.

.

.

It isn’t known whether the removal of the references to the presence of indigenous people was part of an agenda to reinforce the concept of “terra nullius” – an uninhabited country – or whether it was simply that the later editors regarded the references as irrelevant for their purpose. Either way, the reinstatement of the presence of prior inhabitants at the time of the first official visit to the mouth of the river by a white European is a significant matter.

.