This is an edited text of my late friend Dulcie Hartley’s short history of “Pulbah Island” in Lake Macquarie. Dulcie’s daughter Venessa has provided the document, the full version is available for download in PDF form.

Pulbah Island, a potential jewel in the crown of Lake Macquarie, has had a most chequered history since European occupation of Australia, ranging from a monastery to a fur farm. Easily accessible by water, it is situated between the headlands of Wangi Wangi and Point Wolstonecroft and comprises 69ha of sandstone and conglomerate, supporting a thick and, in places, nearly impenetrable scrub, interspersed with eucalyptus species. Shallow beaches are found on the northern shore, and the remainder is steep and rocky with a few shoreline caves. In prehistoric times it was of great significance to the Indigenous people who inhabited the Lake Macquarie district. They knew the island as Boroyirong, home of a monster fish called Wau-wai.

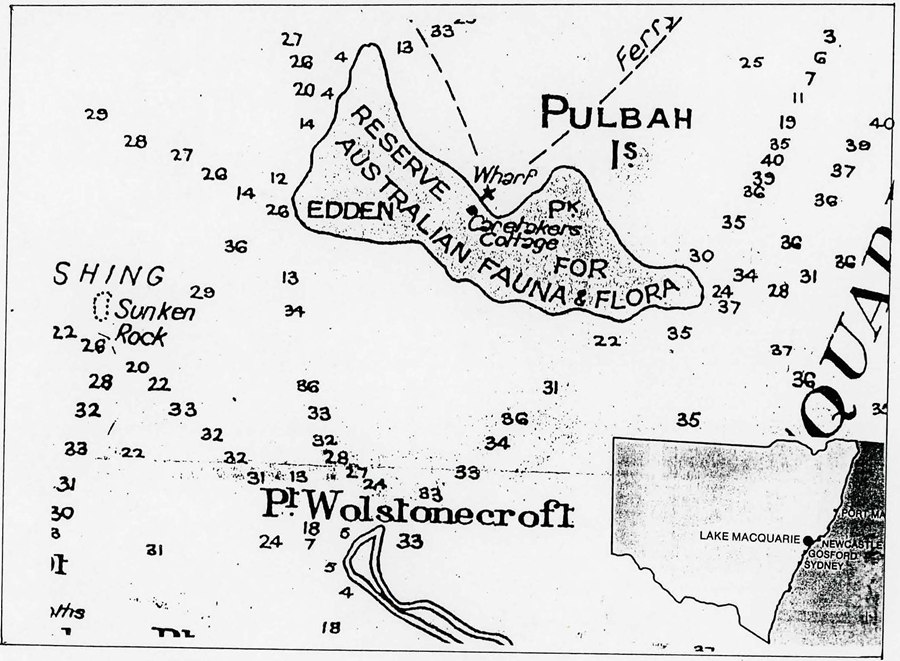

The name Pulba was first used by Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell on his map of New South Wales published in 1834, although an 1828 map shows the name Boroyirong. The names Bulba and Pulba(h) are thought to have been derived from the Aboriginal name for an island. An alternative and little used name was acquired during the early years of the twentieth century. Maps show that the island was then a reserve for fauna and flora named Edden Park, commemorating Alfred Edden, Labor Member for Kahibah in the Legislative· Assembly, and later to become Secretary for Mines.

Indigenous significance

After the first European settlers took up land around the shores of Lake Macquarie the island became a favourite site for shooting and fishing parties, as well as commercial fishermen who netted the shallow northern area. On one camping holiday during the early 1870s William Harris Jnr, son of the licensee of the Co-operative Inn at Wallsend, introduced a pair of rabbits to provide sport for hunting parties, and of course these pests soon ran wild. These feral animals were the forerunners of many other exotic and native species to be introduced during the succeeding one hundred years.

From the early 1870s timber-getters set up mills on the island, moving all their gear and bullock teams over by punt from nearby Wangi Wangi and Point Wolstonecroft. Timber was felled for pit props and railway sleepers and taken by lighter to Millers Wharf on Brush Creek at present day Edgeworth, where it was off-loaded on to wagons and drawn to the Wallsend coal mines. There were extensive stands of spotted gum and grey ironbark, both popular with local shipbuilders. By 1887 Lake Macquarie timber lighters were also off-loading at Cockle Creek Wharf near the railway station, for transport on the new railway line and later on at Dora Creek Station. As the land was cleared native grasses flourished, providing grazing for stock and landholders took advantage of this, either swimming cattle over or ferrying them across by punt. At that time there was a natural soak providing sufficient water for stock.

Great quantities of shells were harvested from the island in the early days as there was a good demand for lime produced by burning the shells and this was. used in the manufacture of cement. The lime was a profitable sideline for commercial fishermen and the lake shores were once fringed with deep shell middens left by the Aborigines.

Perhaps the most interesting phase in the history of the island commenced. in 1917, with the formation of the Dalley Branch of the Australasian Society of Patriots, a group of local visionaries – men of substance such as Harold Morris Cohen, President of the Society, John J. Moloney, Secretary and John Sharp, Field Naturalist. Within a short time the Dalley Branch had over 200 members who supported a vision for the island which had become known as Bulba. The Society aspired to transform the island into a ‘Miniature Australia’, and several Aboriginal families were to be encouraged to settle there. The Trust wanted to re-site three Aboriginal families from Queensland and stock the island with animals and birds indigenous to Australia.

On 5 December 1920 Reserve No. 53667 was gazetted as a special sanctuary for birds and animals indigenous to Australia. A permit from the Bulba Trust was required for visiting parties and fairly stringent conditions applied to the Reserve. It was an offence to damage any animal, bird, plant, shrub, tree, fence, boat, building, wharf or other property of the Trustees. It was an offence to obstruct an officer of the Trust in the performance of his duty and dangerous materials such as bottles, broken glass and litter were not to be left on the island. Trustees could demand that moored vessels around the island be removed.

Wildlife slaughtered

Many Newcastle and Lake Macquarie citizens did not approve of the grand plan envisaged by the Society and were displeased with the dedication of Bulba as a Reserve. Resenting the news that their former easy access to the island would now be difficult and wanting to retain the status quo, the hunting, fishing and camping groups created strong opposition. And indeed, as events unfolded, it may well be that their early opposition foreshadowed the failure of the venture.

In 1921 the Bulba Trust, a group empowered by the Society of Patriots to administer the affairs of the island, arranged a visit by Mr T. C. Mutch, Minister for Education. The Trust was seeking his support in promoting the educational assets of the Reserve through the school curriculum. Secretary Moloney, while conducting the minister on a tour of inspection, explained some of the problems being encountered by the Trust. Twelve months previously the island had been stocked with native animals, but within one week they had all been destroyed. Funding was desperately required for a resident caretaker and the Trust hoped that the Minister would make efforts on their behalf.

On a subsequent visit Le Souef assured the Trust that the rats which seemingly over -ran the island were the Australian marsupial rat, at that time very rare on the east coast. He suggested trapping and selling specimens to zoos as a source of revenue. Goanna were also plentiful and Le Souef, every mindful of operating costs, suggested selling these as well. There was adequate water on the island in those days and Le Souef commented that in earlier times Bulba had carried an extensive stock of kangaroos, wallabies, bandicoots, echidna and other species, all sustained by natural herbage. As well, the mature eucalypts had once supported an extensive population of possums, koalas, gliders and climbing kangaroos. Fig, kurrajong and cedar trees had been planted by the Trust to encourage bird life, and all were doing well, as was the Rhodes grass planted for pasturage. A site had been chosen for a jetty and plans drawn up for a resident ranger’s cottage and administration building.

Society members had now planted some 600 berry fruiting trees as food for the fauna, with many hours of voluntary work expended on improvements. Yet once again sabotage occurred in 1924 when hunting parties with guns and dogs destroyed nearly all the animals and birds. Letters from district residents published in the local newspaper emphasised that the island had been open to the public for too many years to expect people to change their ways, and this was the reality of the situation.

The unsung hero of Bulba was John Sharp, field naturalist for the Australasian Society of Patriots and one of the Trustees. When the Society first discussed the grand plan for Bulba John Sharp, as an experienced field naturalist, was asked to investigate the possibility of success. His report was most enthusiastic and no doubt influenced the Trust to proceed. The Bulba Reserve was continually hampered by shortage of funds but Sharp, botanist, horticulturist, field naturalist and taxidermist extraordinaire, was so committed to the Society’s aims that in 1925 he left a well-paid position to manage the reserve on lower pay. While at Bulba his salary was not always forthcoming, and many times he had to write and remind Mr Moloney to pay him. His endurance was to be admired for initially he camped in a humpy, and it was not until early in 1928 that the caretaker’s residence, an asbestos iron roofed building on concrete foundations with a concrete chimney, was erected. At the time there was no money for furniture and resident naturalist Sharp plaintively requested the supply of beds and mattresses from the Trust, as he and his assistant Mr Palmer were fed up with sleeping on sugar bags.

Unfortunately unwelcome visitors continued to be drawn to the island and vandalism was a never ending source of concern for John Sharp. He had a large area to control and fires were often maliciously started, with others carelessly left by illegal overnight campers. He faced an almost impossible task. In 1930 the Great Depression was underway and times were increasingly tough in Newcastle and Lake Macquarie. It was an era when unemployed men provided for their families with whatever they could catch, shoot or even steal. The dumping of domestic cats on the island had been a great worry for Sharp and two of these, stuffed and mounted, formed part of the display, no doubt as a deterrent. Some professional fishermen were particularly troublesome as they had netted the northern shore of Bulba for many years. Now that it was a Reserve they were supposed to obtain permission to stay overnight, but of course this did not occur. Adding insult to injury, they commenced stealing water from the cottage tank. In 1930 the situation deteriorated into open warfare when Sharp’s rainwater tanks at the cottage were holed near the bottom, a wanton act of vandalism, and fires were deliberately started all over the island.

Wanton acts of vandalism

Sharp, with only one assistant, faced an almost impossible task attempting to fulfill the instructions of the Trust so any additional help was greatly appreciated. Fortunately his dedication continued and in 1930 this remarkable man, an accomplished artist, forwarded two sketches of Bulba to Moloney for use as postcards. He advised Moloney at the time that the possum population had not increased sufficiently to commence slaughtering for skins. As well, he commented on the extent of lantana infestation which was spreading rapidly. A concrete wharf had recently been built extending into the lake and this was a great convenience for the many visitors who were now greeted by Marie the inquisitive emu and Topsy, the baby kangaroo.

As the eventful year of 1930 drew to a close the long-suffering John Sharp decided to leave Bulba and resume his career in government employ. The next caretaker was Thompson Noble who remained on Bulba until 1934. He had trained in England as a pattern-maker but ran away to sea at 16 years of age. On his return he finished his trade and worked for a large engineering firm. An amateur field naturalist, the confines of a factory presented a bleak picture so he migrated to Australia. Like many others, he was unemployed at the height of the depression so the prospect of board and lodging on Bulba for services as caretaker was an attractive alternative to life on the dole. A succession of caretakers were to follow Thompson Noble, mostly of short duration, including Bert Roset, Joseph Venner and, in 1937, E Ralston.

Great concern was felt for the animals during the summer drought of 1940 which left the dams nearly empty and the island devoid of grazing grasses. A windmill was donated to the Trust so underground water could be used to fill the dams. As well, donations were received from the RSPCA for the purchase of food for the animals. It was always feast or famine and the improved conditions resulted in increases in the population. There were now an estimated 180 possums, 7 kangaroos, 50 wallabies, 2 koalas, 2 emus and 3 echidnas. It was decided to reduce the number of wallabies by introducing them into National Parks but shooting parties were sighted on the island, doing their bit to reduce the population. As a result the Trust decided to have Ralston sworn in as a special constable and to provide him with a more modem launch.

By 1941 Mr and Mrs Ralston had left the island and Norman Hunt was employed as caretaker. The financial position of the Trust had improved with a grant from the government of $500 and funds from the Trustees, together with landing fees and donations. The late Misses Parnell of Cawara , Ashfield – committed conservationists – had made generous donations to the Trust over the years and had left a legacy of $600. At this time money was desperately required for improvements to the homestead and for work on the 1.2ha park on the north side. As well the 5ha animal enclosure where picnic facilities were located required new wire netting. At this time the Chairman of the Trust, Lake Macquarie Shire Council Alderman F. J. Dorrington, estimated that there was a surplus of 100 wallabies and thought it imperative that they be removed. National Park authorities had promised some 12 months previously to trap and removed them, but this had not occurred.

Succession of caretakers

The Second World War was now in progress with the action moving closer to our shores and the caretaker, Mr Hunt, decided to enlist in the armed forces, leaving a vacancy that was probably difficult to fill with manpower directed towards the war effort. However, the Trust was fortunate enough to gain the services of Mr and Mrs Carl Anderson who spent the years of 1941-43 on the island. Mr Anderson, a Swedish ship’s carpenter, made many improvements to the cottage and grounds and visitors continued to pay homage to the native animals.

In February of 1942 Japanese bombs fell on Northern Australia, with the result that F. J. Dorrington was informed by the Under-Secretary for Lands that no additional expenditure on the island was to be incurred. All government finance was now re-directed towards the war effort. An inspection of the island was made by the Surveyor-General with Mr Dorrington to determine its future. Sadly, the outcome was that the Reservation covering Bulba was to be revoked by the minister for lands, and was to be re-notified for Public Recreation and Camping under the control of Point Wolstonecroft Reserve Trustees. Thus ended the experiment – a Reserve for Study and Promotion and Preservation of Flora and Fauna.

It was generally conceded that after the deaths of the promotional parties, John J. Moloney and H. Morris Cohen, a lack of motivation and enthusiasm had occurred, resulting in ineffectual management of the Trust. As well, the paucity of funding had played its part in the failure of the scheme. The outbreak of the Second World War had exacerbated the problem, with resultant labour shortages and tightening of government purse strings.

All was not lost however. Point Wolstonecroft, under the control of the National Fitness Council, was to be offered the use of the island for a Nature Study Centre. Although the Lands Department was now responsible for the island, Mr S. Delves, Regional Officer for the National Fitness Council, said they would welcome the rights to Pulbah. [Evidently a new image was proposed with the re-notification of the island. The old Bulba name had now been replaced by Pulbah Island.] Authorities promised money for a hostel and other facilities. By this time, 194 7, the island was a sorry sight, with the caretaker’s cottage vandalised and the launch, earlier purchased with government funding, now missing. Apparently this National Fitness takeover did not occur for in 1949 Lake Macquarie Shire Council was requested to assume control of the island. Councilor Gain though it would be a great asset for Lake Macquarie Shire Council, but realised maintenance costs would be high and a new caretaker’s cottage would have to be provided. After the dismantling of the Bulba Trust the Lands Department had administered the Reserve with funding by way of an annual grant which had paid the wages of a caretaker, but this had ceased some time back.

Unbelievable as it may seem, in 1964 Lake Macquarie Council had no idea which government department controlled Pulbah Island. [Evidently the Council was not receiving any rate payments]. Council was now interested in the tourist potential of Pulbah, but ‘so far as the authorities are concerned, it seems to be a forgotten island’ said Councilor Dunne. Before long Council adopted the same attitude. Official interest was rekindled in 1969 when Mr James MHR proposed restoring Pulbah as a Sanctuary for Flora and Fauna, with a new caretaker’s residence and jetty. A water pipeline from the mainland was also mentioned at this time.

A forgotten island

The saga continued and by 1972 Pulbah Island was under the administration of the National Parks and Wildlife Service and with the introduction of 36 Parma wallabies, including 6 breeding pairs, the island again became an animal sanctuary. In earlier days these wallabies had been indigenous to the NSW coast, with particularly large colonies in the Wyong-Gosford district, but over the years the species had become extinct. During the early days of the twentieth century Sir George Grey, Governor-General of New Zealand, had imported Parma wallabies for hunting. By 1972 the species had run wild in New Zealand and methods of culling the population were being discussed. When Australian zoologists heard of this they eagerly imported the wallabies for re-stocking.

Taronga Park Zoo was a recipient and many Parma wallaby were forwarded to Pulbah Island, under care of the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Mr M Hunter MLA warned the public that once again Pulbah had become a closed native animal reserve and people who were caught shooting or harming the animals would be severely penalised. Within three months hunters were wreaking the usual havoc on the wallabies. Despite the depredations by shooters, the wallaby population increased to such an extent that pasturage became scarce during the hot, dry summers, and there were reports of animals starving. As well, incredible as it may seem, horses had become a problem on the island. They were mostly strays that reportedly swam to the island for grazing during droughts and were competing with the native animals for feed.

Over the succeeding years there have been many ‘clean-up days’ of the neglected and degraded island. These are often arranged by concerned conservation groups whose enthusiasm usually declines, mainly due to the isolation and difficulty of access. In an attempt to avoid casual littering on the island at one time the National Parks and Wildlife Service provided rubbish containers which were emptied monthly. These, however, were stolen so the island today presents a sorry picture of neglect.

Legends abound regarding the past history of the island, some adding a touch of mystique. The Aboriginal name Boroyirong changed to ‘Bury-your-own’ at one time. A European couple was supposed to have lived on the island last century and when the man died the woman buried him there. Another explanation of the name concerns a crime passionate during which the woman was fatally injured and the victor was said to have told the other man to ‘bury your own’. The concept of a monastery on the island died a natural death, as did the once flourishing two-up school held in one of the caves on the western shore.

It seems that every scheme proposed for the island has been a failure. Perhaps officialdom is now running out of ideas as it is over 20 years since any radical usage has been discussed. In the meantime the island slumbers on, still providing interest and shelter for visitors.

Dulcie’s full document can be read and/or downloaded by clicking here.