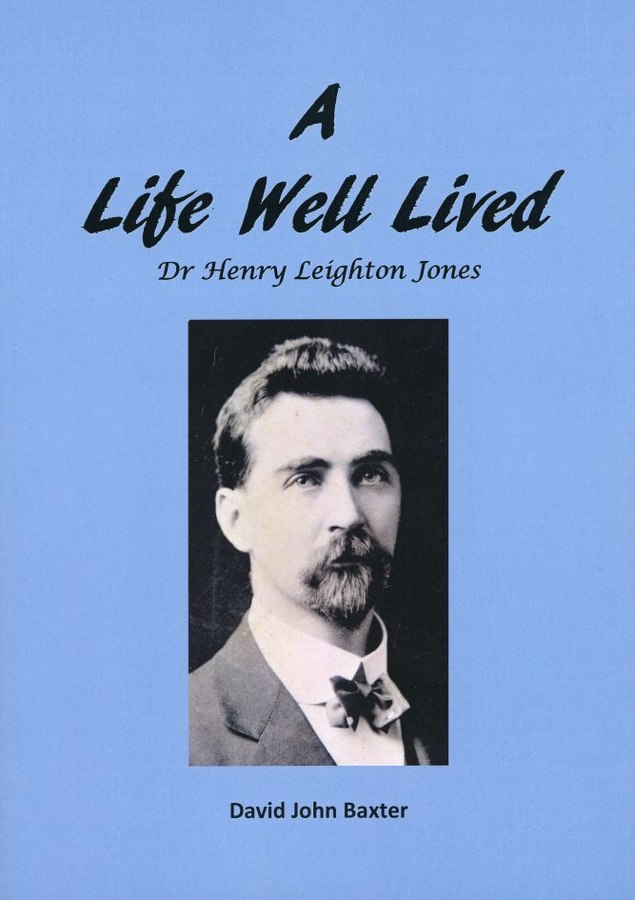

Dedicated to my dear friend, the late historian Dulcie Hartley, whose long-time fascination with Dr Henry Leighton Jones led to many interesting discussions and many lines of research.

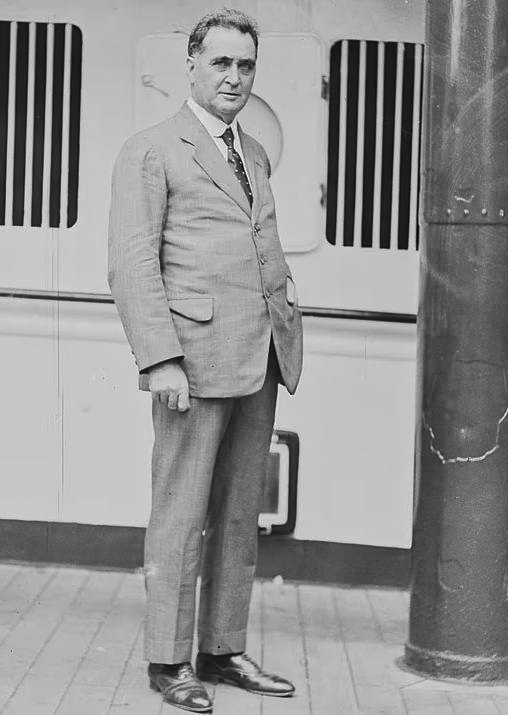

By the 1920s when Australian doctor and dentist Henry Leighton Jones heard the news that, in far-off Europe, a highly respected surgeon was apparently revitalizing the energy of ageing men by grafting onto their testicles pieces sliced from those of baboons, chimpanzees or monkeys, he was himself already 60 years old, single, and missing a kidney. Not that he was, by all accounts, frail or sickly. Far from it. An extravagantly qualified, wealthy and well-travelled man with a remarkable career already behind him, he was apparently vigorous for his age.

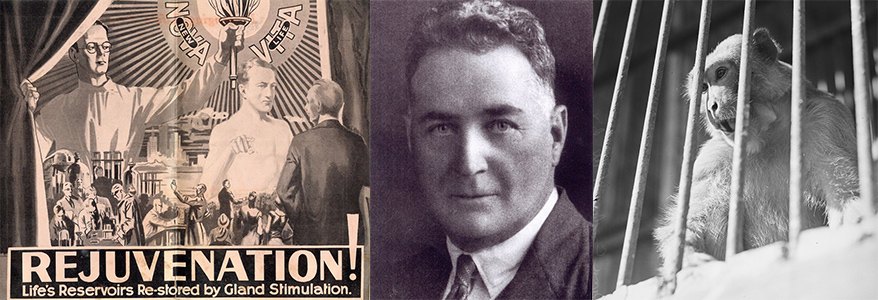

He was, however, extremely interested in the emerging medical discipline of endocrinology – the study of glands, their secretions and effects – and it seems he was personally attracted to the promise offered by the work of Dr Serge Voronoff, the world famous “monkey gland doctor” of Paris. Voronoff was an extraordinary character. Of Russian-Jewish parentage, Voronoff had studied medicine in France, become a French citizen and developed a fascination with surgical transplantation. By 1910 – aged 44 – he had outlived his first wife and 10 years later he married again, this time into a fortune. His second wife was Evelyn Bostwick, daughter of one of the founders of the Standard Oil Company. She had worked with Voronoff from about 1917, but only lived a year after their marriage in 1920 (having translated Voronoff’s book – Life: a means of restoring vital energy and prolonging life – into English). When she died, she left Voronoff a large fortune that bankrolled his famous and lucrative business, operating on rich elderly men who wanted to recapture the vigour of their youth.

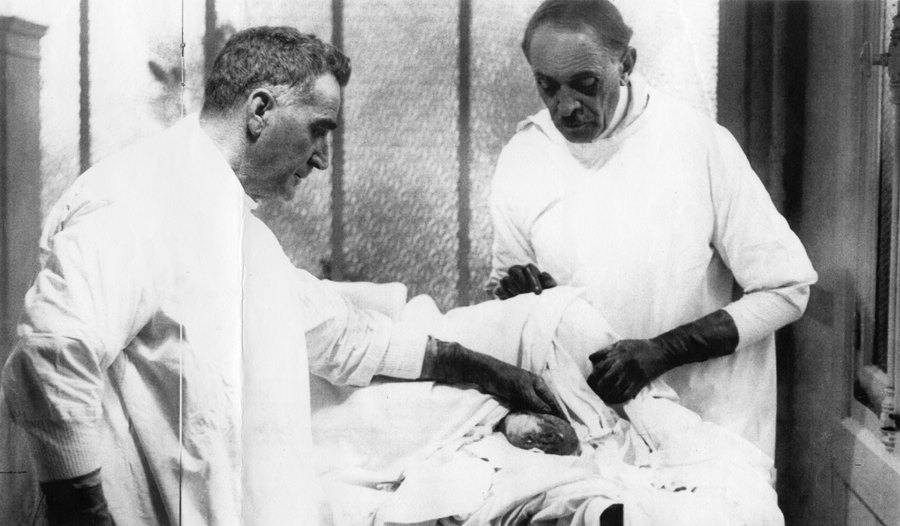

Monkey gland transplantation was a trend in the 1920s. Then considered scientifically valid by many in the medical profession, it attracted large numbers of well-heeled patients who paid handsomely to go under Voronoff’s knife.

When Henry Jones arrived in 1929 it was as a patient and a would-be mature-age student, eager to learn the procedure and take it home to Newcastle, Australia where, no doubt, the wealthy old men of the colony would flock when word got out that the famous Voronoff rejuvenation operation was available to them, at a price.

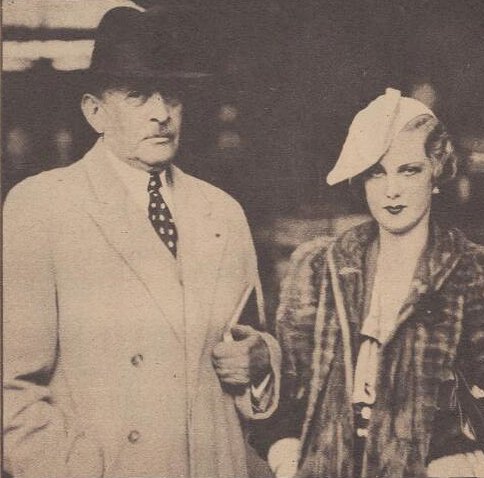

Dr Jones got his wish and much more. He had the operation, learned the procedure, became a great favourite of Voronoff and also of Voronoff’s private secretary, Nora Barrett, who came back to Australia as Henry’s wife and professional assistant.

Back to Henry Jones

Henry Jones came from a family of battling Welsh immigrants to Australia. His parents, John and Mary Jones, had left Wales for the coal-mining Hunter district of New South Wales in the early 1860s, settling at Winding Creek, near Cardiff, where they were able to get some grants of farming land. He was the fourth child in a family of eight, later to increase by four children from the second marriage of widowed John Jones.

Henry went to Hillsborough Public School, leaving at 14 for a clerical job with the Great Northern Railway Extension at its Cockle Creek camp. He went to night school to matriculate and found an apprenticeship with a pharmacist. By the time he was 20 he had finished his apprenticeship and he then did locum work around the state until 1893. There is a story that his family received some money from coal found on their land, but I have seen no authority for this. Somehow – perhaps by sheer frugality – pharmacist Henry Jones was able to afford a trip to the United States where he studied dentistry at Northwestern University in Chicago. Back in Australia he set up dental practice in Moss Vale, NSW, and managed to become friends with the state’s governor – a helpful business contact. In 1899 he had to have a kidney removed, a procedure that slowed his career and encouraged more travel. He qualified as a dentist in Kentucky, USA, in 1901. It was here at this time also that he decided to change his name from Jones to Leighton Jones – adopting the name of the residential college where he was staying. According to a short biography by Henry’s son John, the extra name was a way to make sure his mail found him, since there were, apparently, numerous Joneses in the area at the time.

Next, wanting medical qualifications that would be recognised in New South Wales, Leighton Jones went to Scotland, first studying more dentistry at Glasgow then medicine and surgery at Edinburgh. By 1902 he boasted a long list of letters after his name and was qualified to practice medicine, surgery and dentistry in New South Wales.

Back in Moss Vale he was elected Mayor of the municipal council in 1904, a role he held for seven years.

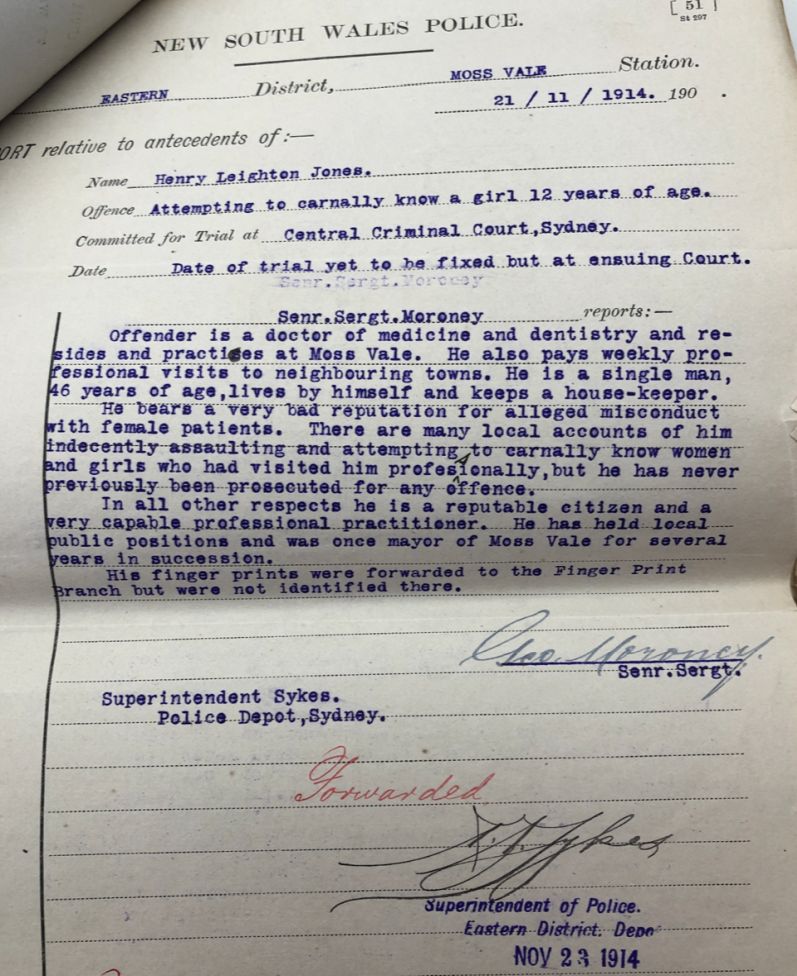

Researcher David Vernon has unearthed a rather unpleasant aspect of Leighton Jones’s career, which may explain his sudden shift interstate in 1915. In 1914 Jones was charged with attempting to carnally know a 12-year-old girl and even though he was acquitted by the all-male jury it may be – based on this document Mr Vernon provided – that continued residence in Moss Vale was no longer tenable.

In 1915, with Australia experiencing the patriotic fever of The Great War, Jones sold his business and volunteered but was rejected on medical grounds. Aged 47 and lacking a kidney he was hardly prime military material. The following year he took a job as Government Medical Officer, Chief Health Officer and Quarantine Officer for Australia’s sparsely populated Northern Territory. This eventful period in his life was reported in a 1943 article in Walkabout magazine.

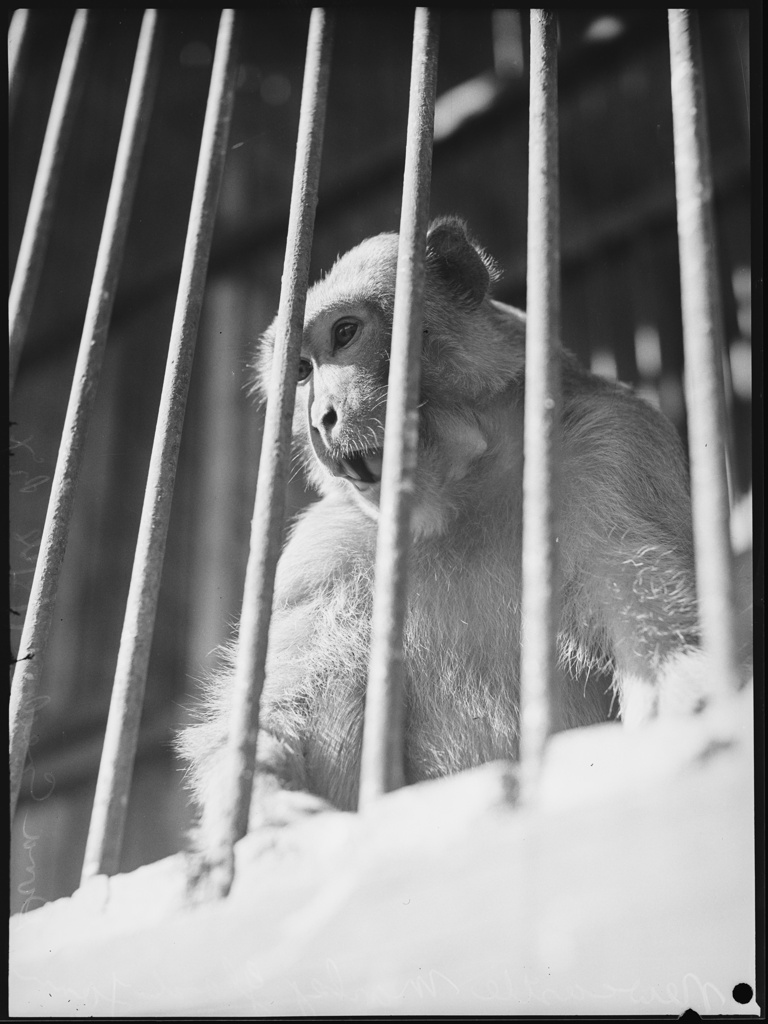

Still in Darwin (Northern Territory) in 1923, Leighton Jones fitted up a schooner and sailed off to attend that year’s congress of the Far Eastern Association of Tropical Medicine in Singapore. He befriended the Sultan of Johore, another excellent business contact whose value would become apparent in later years when a supply of monkeys was required.

Now interested in endocrinology, Leighton Jones, having quit government service, decided to visit the famous monkey-gland doctor, Serge Voronoff, in Paris. He taught himself French from Linguaphone records and set off on another curious career adventure.

Leighton Jones and Voronoff appear to have struck up a very close friendship. Leighton Jones achieved his wish of learning the gland-grafting procedure and spent a year working with the eminent Parisian. He also struck up a rapport with Voronoff’s bilingual personal secretary, Nora Barrett, 30, who had gone to France from England to recuperate from an illness before finding employment with the surgeon. She and Leighton Jones were married by the British consul general in Paris in 1929.

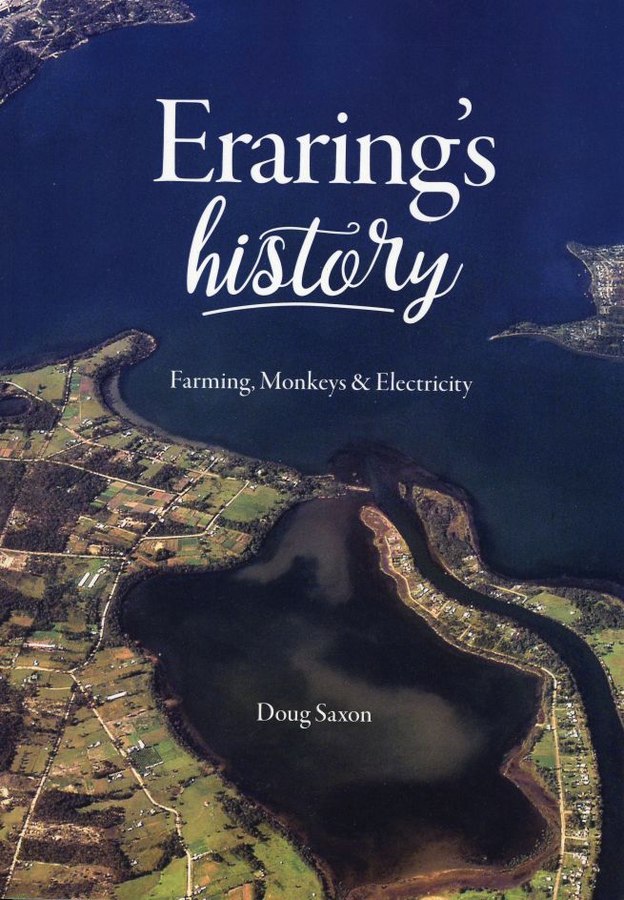

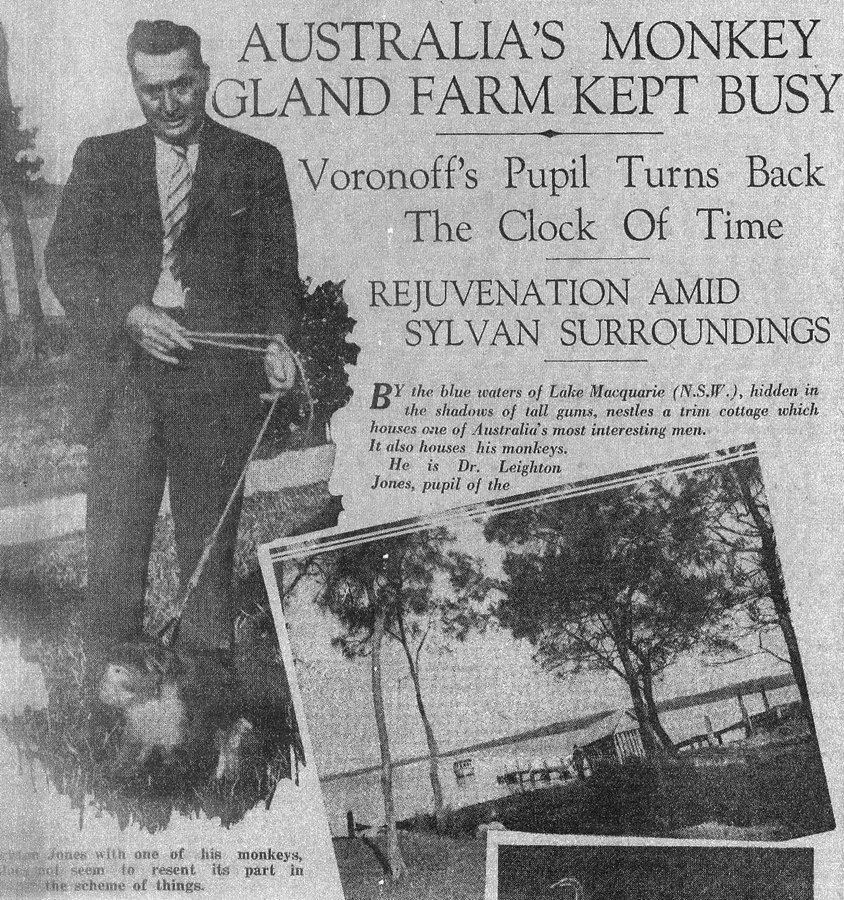

Back in Australia the newlyweds moved onto a property at Dora Creek, Lake Macquarie, near Newcastle – not far from Henry’s birthplace. It isn’t known whether his gland-graft operation improved Henry’s physical capacities, but in 1931 the couple’s first child, John Serge Leighton Jones was born. Their only other child, Elisabeth Sergine Leighton Jones, was born in 1939. The Dora Creek property was expanded and improved, the house extended and renovated and a well-equipped workshop built. Two tall cages, capped by water tanks, were also built to accommodate the various types of ape that were to be imported for the gland-grafting enterprise.

The beginning of Dr Jones’s monkey business coincided with the onset of the Great Depression. Also by the 1930s the fad was beginning to fade on the Continent as critics began to multiply and the procedure started falling into disrepute. Nevertheless, the Sun newspaper reported on September 9, 1931, that “in a little hospital at Morisset, 76 miles from Sydney, the first Voronoff rejuvenation operation on humans in Australia has been successfully performed by Dr Leighton Jones”. The two human patients were reported to be well, as were the monkey donors, thought it was reported the men would have to wait about “six months before the rejuvenation effects can be expected to show up”. Dr Jones was reported saying that “he had made long and careful preparations to ensure the success of his business and he had not the slightest doubt that it would fulfil all the expectations held of it”.

It is understood that the first donors were Abyssinian baboons, but the Sun reported that Leighton Jones had government approval to import eight rhesus monkeys – obtained, apparently, with the help of his old friend the Sultan of Johore.

In 1933 the Jones family went back to visit Europe, taking a pair of kangaroos for Dr Voronoff’s private zoo.

It is estimated that between 1931 and 1941 Jones did more than 40 gland grafts. These included four thyroid grafts on children suffering from “cretinism”, pituitary and ovarian grafts and, of course, testicular grafts. In later years it was said that Leighton Jones didn’t like publicity, but the evidence doesn’t really support this. Articles appeared in numerous publications, drawing attention to the availability of his unusual service.

In an article in The Daily Telegraph on January 28, 1936, Leighton Jones told the reporter that people who had the operation felt no pain and had little reaction. They could “get up in a few days and leave the hospital after a week or two.” “The effect of the graft is not immediate”, the article continued. “It slowly increases to a maximum at six months afterwards, retains this level for three years, then slowly declines, til in five years’ time, the patient is as he was before. The march of time, according to Dr Jones, has been halted for this period, during which the active principles of the gland have been slowly absorbed by the system, imparting the mature vigor of the young healthy animal from which it was derived. Speaking of his patients, Dr Jones said that in every one of his 50 cases the effects, as far as could be traced, were satisfactory. Mental and physical vigor were increased, several had returned for a second graft at the end of five years with a history of sustained reinvigoration over that period.”

According to John Leighton Jones, his father’s surgery was “rather unusual”. “The first thing one saw on entering was the gun rack, containing a Martini Henry buffalo gun, two sporting rifles and two shotguns. On the floor was a large iron safe. One was was taken up with books, another with cupboards of pharmacy requisites and a bench with mortar and pestle and spirit-burning sterilizers. There was a large glass-fronted cabinet containing instruments. The furnishings consisted of a desk, two consulting chairs and a dental chair with foot-operated drill,” John wrote.

Monkeys occasionally escaped from their enclosures and were either trapped or shot. When required for surgery, the apes were put in special cages and strapped to Jones’s car, ready to be taken to the hospital where the operation was scheduled. Two operating theatres were used: one for the monkey and one for the human. The monkey was knocked out with nitrous oxide while the human received only local anaesthetic. A slice was taken from the monkey’s testes and inserted onto the exposed and scarified surface of that of the recipient. Little is known about the results, but it is known that Dr Jones was well aware of the risk of tissue rejection and took pains to try to match donor with recipient in terms of blood type. It is thought that, in this way, he may have accidentally discovered the Rh factor, later to become so important in medicine.

World War 2 cut off the supply of monkeys and brought an end to the business. It didn’t make Dr Jones less busy, however. With many local medical people now in uniform, he was busier than ever in his triple roles of doctor, dentist and pharmacist. He is reputed to have never refused a home visit and is also understood to have had a charitable attitude towards his less well-off patients.

Much more would surely be known about his practice, and especially his gland-grafts, if it weren’t for his sudden death in 1943, just before he was due to present a paper on the subject to postgraduates at Newcastle Hospital. He had already sat through some other papers when he left the room. Witnesses said he looked ill. He collapsed and died of a heart attack. Many of his records were written in a private code, to protect the identity of his clientele, and nobody else could locate the key. Ultimately, most of the papers relating to his medical work were destroyed.

As years passed the legend of “the monkey doctor of Dora Creek” persisted and morphed into many forms. One writer suggested the doctor’s home was seen by some as a kind of “sexual Shangri-La”. The truth was different, but still very strange.

In 1973 Newcastle Herald journalist Percy Haslam interviewed some people who had once worked with Dr Leighton Jones and they shared their reminiscences. Oscar Smith and Arch McKinnon had been nurses at Morisset psychiatric hospital for years, and had long remained silent about their roles in the gland-graft operations at “Matron Lower’s private hospital” in Macquarie Street, Morisset. Haslam’s article reported that the original transplant team was Dr Jones, Dora Creek GP Dr H. Donellan, two theatre nurses and Mr Smith, who shaved the monkeys and acted as anaesthetist. Patients were admited under aliases and the identity of only one – a haulage contractor named Carson – became widely known. Carson allegedly regarded the operation as so worthwhile he came back for another one after the effects of the first wore off. Or so the story goes . . .

In 1996, prompted by historian Dulcie Hartley, I wrote an article in The Newcastle Herald about Leighton Jones. This article was seen by Moss Vale historian David Baxter, who contacted Dulcie hoping she could help him find family members of the late doctor. A bank in Moss Vale had found some metal canisters belonging to Henry Leighton Jones in one of its vaults and wanted to give them to descendants. The introduction was made, via Dulcie, and the material – which proved to be the doctors’ original certificates and qualifications – was handed over.

John Leighton Jones’s brief biography of his father – prompted by the return of the documents – is tinged with some sadness. His parents were not the doting kind, and were in fact very strict disciplinarians prone to corporal punishment. Both children were sent to boarding schools at the earliest opportunity and, according to John: “the other children thought we were orphans, as we never had a parent attend a school function.” It’s a credit to John that he was able to see past this deep grievance and assemble, late in his own life, a respectful biography of his interesting father.

Dulcie Hartley’s unpublished article about Leighton Jones can be read here.