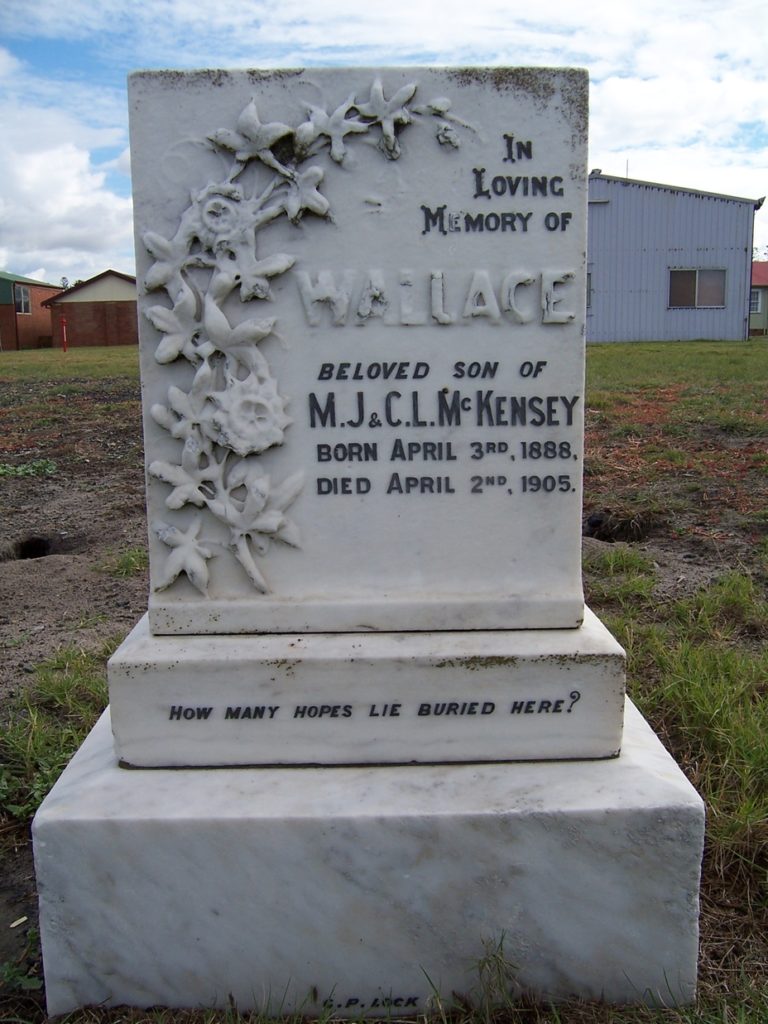

There is (or was?) an unofficial car park at the eastern boundary of the Stockton Centre where fishermen would leave their cars before walking to the beach. Beside the wooden barriers that marked the car park’s edge stood a lonely tombstone. The inscription told of a teenager’s untimely death on April 2, 1905, just one day before his 17th birthday. At the foot of the white marble monument is a century-old question that asks passers-by to reflect on the long-forgotten heartbreak of a Newcastle family: “How many hopes lie buried here?” The name on the tombstone is Wallace McKensey, son of M.J. and C.L. McKensey, but the monument gives no more clues to the boy’s identity or why he lies alone in the sandy soil on the edge of seaside dunes.

A former staff member of the Stockton Centre had telephoned me at The Newcastle Herald to tell me about the grave, leaving an anonymous message on my answering machine. She described how she had often walked by the solitary grave, wondered about the youth and pondered the sorrowful inscription.

I had accidentally supplied a partial answer to her questions in a column I’d written about news events of a century ago. The first of a series of items I quoted from the pages of The Town and Country Journal described the death of Wallace McKensey, 17, a victim of an outbreak of bubonic plague in Newcastle.

When she read the column I wrote, the staff member phoned to let me know about the lonely headstone. Interestingly, another former staff member, Ena Furness, wrote to me that the headstone photographed above was not the same stone she recalled during her time at the hospital, from 1969 through the early to mid-1970s. “As I recall, it was quite small and either flat or wedge-shaped, facing the sea, and simply inscribed with his name (not his parents’ names), the dates of his birth and death, maybe his age – 17 years- and the inscription which is forever in my memory, and very apt in view of his youth, ‘What Treasured Hopes Lie Buried Here?”.

Intrigued, I visited the grave and then searched for copies of The Newcastle Morning Herald from March and April 1905. Sure enough, I found reports of the plague outbreak and an account of the admission of Wallace McKensey and a handful of other people to Newcastle Hospital.

Some extra research suggested that young Wallace’s father may have been a baker, working and possibly living at a shop at 181 Hunter Street, Newcastle. The baking business appeared to have been owned by a Mrs A Wylie.

In recent times (February 2019) this information was confirmed by a living relative of the late Wallace, Mrs Alison Bencke. Mrs Bencke said Wallace was the son of Morse James McKensey and Catherine Lawson McKensey (nee Louden). The baking business bore the name Wylie’s, as Morse’s mother Aleathea had remarried a baker named James Harvey Wylie after her previous husband James McKensey was killed in a horse accident at Hexham in 1856.

Wallace McKensey was, by all accounts, a youth with much in store for him. He’d gone to West Maitland High School for three years, before studying at the Collegiate School. Shortly before his death he’d been offered a job in Sydney at the Barrack Street Savings Bank and on March 20 he’d gone to the city to make arrangements. He was due to start his new job on Monday, March 27. But according to his obituary he’d come home to visit his parents on Wednesday the 22nd. The pages of The Herald revealed that cases of plague had been reported elsewhere on the NSW coast that year, with a woman dying of the disease in Ballina during March.

Wallace McKensey appears to have been the first diagnosed case in Newcastle, and one of very few fatalities in an outbreak that was quickly contained. But while the plague panic lasted, the population of Newcastle was galvanised into action, declaring war on rats, disinfecting sewers, burning tons of rubbish and goods from homes where plague cases were found, quarantining whole blocks of shops and houses, tearing up floorboards and ripping out ceilings in dramatic clean-up operations.

City block quarantined

Plague occurs in rats and is spread by fleas. The disease periodically kills off large numbers of rats and the fleas are forced to search for other animals to bite. When they bite, they pass on the plague. When doctors diagnosed McKensey with bubonic plague, health authorities searched his house but found it clean. When they took out the ceiling they found four dead rats. The entire block bounded by Hunter, Crown, King and Brown streets was quarantined, shutting down the McKenseys’ business premises. All that was found in the whole block were 27 rats and three mice – all well and truly dead. Wallace McKensey was soon joined in the isolation ward of Newcastle Hospital by other victims of the plague.

Across Newcastle the various councils issued anti-plague decrees. Householders were ordered to clean their properties and the garbage carts were continuously circulating. People were warned that if they hadn’t finished cleaning up within a week, they’d be prosecuted. Newcastle Mayor Alderman Moroney declared a rat crusade on the nights of April 4 and 5, urging residents to properly dispose of rubbish and also to lay poisonous baits which were handed out by council employees. Dozens of council men were put to work catching rats and cleaning houses and neighbourhoods. Ratcatchers were brought up from Sydney to help.

The city was primed for action before this outbreak since, a few years before, there had been a major plague scare in Australian port cities. After a plague death in Sydney in 1900 Newcastle authorities had a massive clean-up, pouring thousands of gallons of disinfectant into drains and sewers, washing streets, inspecting suspect premises and setting hundreds of poison baits for rats along the waterfront.

A rat incinerator was set up at the foot of Merewether Street and a site for a plague hospital was selected at Stockton. This site became known as the quarantine ground, and is now part of the Stockton Centre grounds. A bounty of sixpence a head was initially offered for rats, and the incinerator destroyed 12,000 rat corpses within days of opening. So many rats were being cashed in that the bounty was quickly lowered to threepence a head. Railway stations and carriages were fumigated. Health workers were inoculated. Buildings deemed too dirty to clean were summarily demolished.

Hotel porter died of plague

The plague didn’t strike hard that time, but it kept returning in fits and starts over the next few years, each time raising some level of panic. In 1902 Thomas O’Neill, a porter at the Criterion Hotel in Hunter Street, took ill with plague and died within 24 hours at Newcastle Hospital. He was buried on the quarantine grounds at Stockton and the Criterion Hotel was given a thorough clean and fumigation.

In 1905, when Wallace McKensey took ill, the rat bounty was set at fourpence a head. Boys crawled into sewers to earn their fourpence, and teams of men brought hundreds of rodents from the slaughterhouse, the docks and from city businesses.

Over at isolated North Stockton, the quarantine station was made ready to accept infected patients, if required. Poor Wallace McKensey’s condition fluctuated wildly, as these paragraphs from The Herald suggest. “When first admitted it was feared that McKensey’s case would prove very serious, but yesterday he took a decided change for the better and last evening his condition was much improved.” “McKensey took a bad turn yesterday and throughout the day his condition was anything but satisfactory but at an early hour this morning showed signs of improvement”. Next he had what the newspaper described as “a series of bad turns” and he died shortly after 1am on Sunday, a day short of his 17th birthday. Monday’s Herald reported that: ”the burial is to take place at seven o’clock this morning at the quarantine grounds, North Stockton.” “Much sympathy is felt for Mr and Mrs McKensey. It is a regulation of the Board of Health that the bodies of all plague patients must be buried in a separate enclosure, and not in the General Cemetery. Ministers are permitted to attend the funeral and there is no objection to the friends of the deceased erecting a headstone over the grave.”

Funeral procession

Wallace McKensey’s funeral procession left Newcastle Hospital early Monday morning. His body was taken by boat from Newcastle to Stockton shortly before 7am. The procession reformed at Stockton, taking75 minutes to make its way to North Stockton where the boy was buried, in final isolation as required by the government regulations, “in the ground attached to the quarantine station”. The Mayor of Newcastle attended the funeral, along with a number of the boy’s former schoolmates. The quarantine was lifted from the Crown Street block a day or two after the funeral, when Mrs A Wylie announced ”the re-opening of her business premises at 181 Hunter St”.

Mrs Bencke said the death of Wallace hastened the demise of both his parents. Wallace’s brother Stanley McKensey trained as a mining engineer and lived until 1970. Mrs Bencke is Stanley’s grand-daughter. Wallace’s sister Myee married into the Pullen family and lived until 1975.

As for Wallace McKensey, his obituary said “he was of a cheerful disposition and the manly qualities he possessed endeared him to all who knew him”. His grave, with its strangely impressive headstone, still lies more than a century later in isolation on its nondescript patch of sandy ground, posing its troubling question to every passer-by.

Robyn Jeffriess, of Newcastle Family History Society, has written that another plague victim, David Davies of Lambton, was also buried at the Stockton quarantine ground, but his grave was never marked. Instead, he was memorialised with other family members at Sandgate cemetery. “The doctor attending him, Dr. J. R. Leslie, also came down with plague but survived,” Robyn wrote.

Robyn wrote of her research that a Thomas O’Neill had been buried in an unmarked grave in the Quarantine Ground in 1902. “The outbreak in 1905 claimed Wallace McKensey (buried there, lone headstone), David Davies, (buried there and memorialized with family at Sandgate) and Charles Edward Jennings (buried in an unmarked grave in the Quarantine Ground). There were 14 people infected in the 1905 outbreak, mainly around the Queen Street area and Newcastle East. A couple were infected in Newcastle West. Those infected were: George Parlota, Wallace McKensey, Robert King, George J. W. Muzzard, David Davies, Dr. J. R. Leslie, Charles Edward Jennings, William McMichael, Daniel Sleishman, Daniel Stewart McLardy, Henry St. Clair Wilkinson, Samuel Thomas, Harry Jones and James McDermott.

Wallace McKensey was my grandfather’s older brother. He also had a younger sister. This tragic death caused the early demise of his parents. However Wallace’s siblings and their children lived honest and very successful lives aware of, but not thwarted by the family hopes buried with 17 year old Wallace.

I found NSW records has a scan of the “bubonic plague register”. Which lists Edward Jennings, of Corlette St , Newcastle dying May, 1905. See https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/bubonic-plague-index

It does also list Wallace.

Also, the trove article about Edward Jennings. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/138384309?searchTerm=edward%20jennings%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits=l-state=New+South+Wales|||l-decade=190