The wartime dealings of Australian Prime Minister John Curtin with his British counterpart Winston Churchill have become the stuff of Australian folklore. Some historians have portrayed Curtin as Australia’s bold saviour, while others have accused him of being a nitpicking panic-merchant. Thanks to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which some years ago made many formerly secret telegrams and cables between the two leaders and other leading figures of the period publicly available on its website, interested readers can make up their own minds.

WHEN wartime Prime Minister John Curtin used to remind Australians that: “part of our heart is locked up in Singapore” there was some bitterness in his statement. For Curtin, it seems, the capture and imprisonment of 15,000 precious Australian fighting men when Singapore fell to the Japanese on February 15, 1942, was the last straw in his strained relationship with Britain and with its Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

When Curtin came to the leadership of Australia late in 1941, he faced a frightening situation in Asia and the Pacific. Britain had since 1939 been fighting for its own life and what remained of its global commerce and prestige. The battle for control of the skies over Britain, the battle to protect vital shipping lanes in the Atlantic, the campaign in North Africa to deny Germany access to Middle East oil and the strategy of giving money and weapons to Russia in order to keep that country’s resources out of German hands: all these demands were costing Britain dearly.

For its part, Australia under the previous Menzies government had sent men, equipment and crucial war supplies to help what it considered “the mother country”. Since the early 1930s Australia had been led to believe that its defence was assured by a global strategy on the part of the British Empire. In this strategy, British interests in South East Asia and the Pacific were to be safeguarded by the modern naval base at Singapore.

When John Curtin came to power Japan was obviously arming itself for a war of conquest. Japan had already been fighting in China since 1932 in a battle to win resources and markets for its goods. When France fell to the Nazis the Japanese occupied its former possessions in Indochina. It seemed certain they would soon make a grab for the oil, rubber and other supplies that Britain and Holland’s South East Asian colonies offered.

While most people seemed prepared to accept the British propaganda that Singapore was impregnable, Prime Minister Curtin had grounds for doubt. There had been many studies of the military position of Singapore through the 1930s and virtually all of them concluded that, to preserve the island against an attack, 400 or more modern fighter planes would be needed, as well as enough men and equipment to hold a substantial part of the Malay Peninsula as a buffer. But in 1941 the British only had a handful of obsolete planes in Malaya to defend a supposed “impregnable fortress” that was really just a big city with a naval base but no fighting ships.

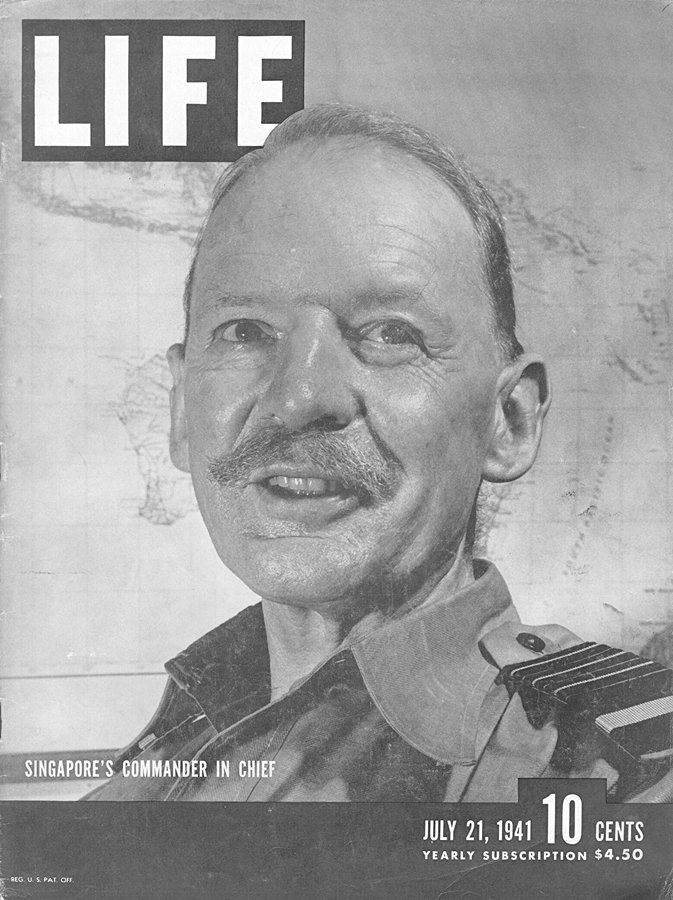

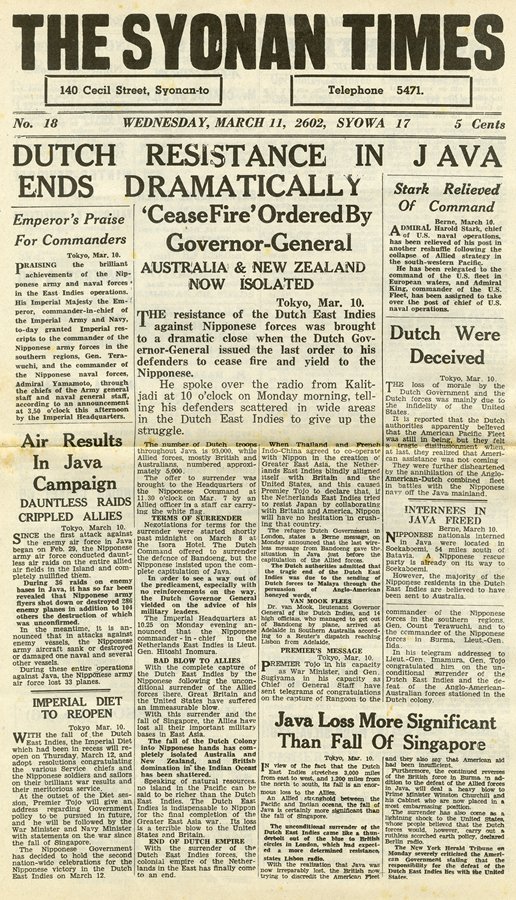

This article from the American Life magazine of July 21, 1941, makes interesting reading. On the face of it, the article talks about the rapid fortification and armament of Singapore, but between the lines the picture of under-preparedness and the sleepy character of the city’s high command seems apparent.

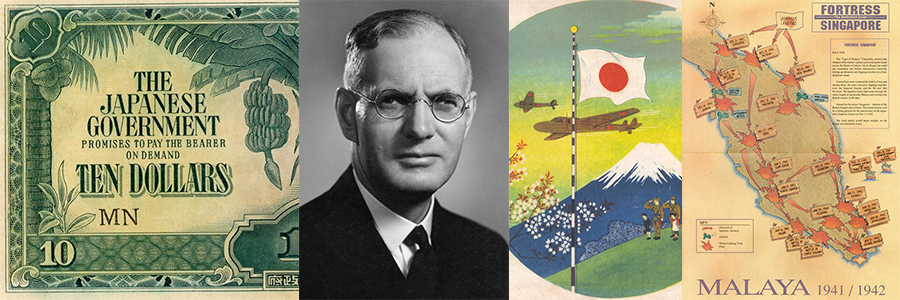

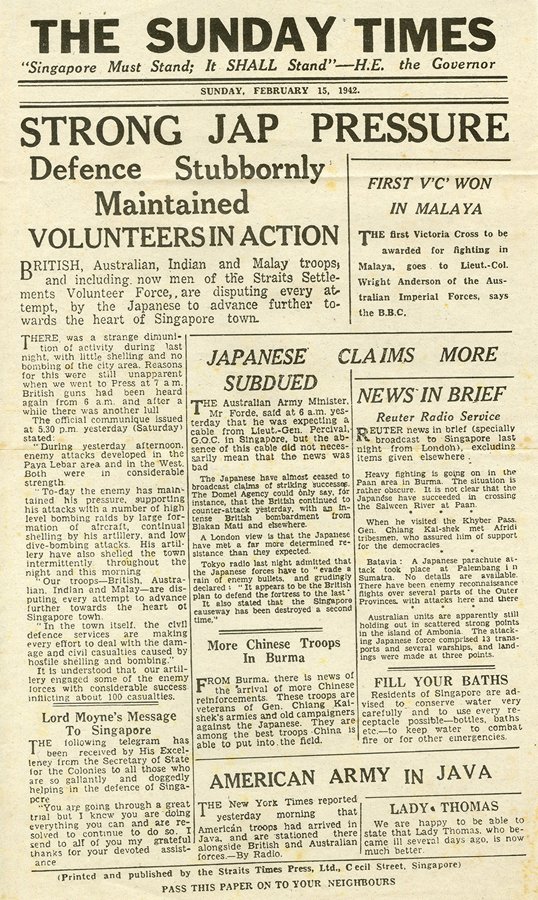

Life magazine, July 21, 1941 (left), the last British news-sheet before the fall (centre) and a copy of the Japanese English-language Syonan Times (right). Syonan was the Japanese name for Singapore. You can click on the items to view larger copies.

If Singapore was the cornerstone of Australia’s defence, Curtin reasoned, then Australia was at serious risk from Japan. A much smaller country to begin with, with a relatively underdeveloped industrial base and poorly equipped military, its limited defensive capacity was further compromised by the fact that it had sent the cream of its armed forces to fight for Britain on the other side of the world.

In those days, though, Dominion governments did not dare question the Mother Country, even if their own fates appeared to hang in the balance.

On December 8 Japan attacked the US Pacific Fleet at Hawaii, sinking a number of ships and killing 2000 Americans. At about the same time Japanese troops landed on Malaya and soon Singapore itself was being bombed. A couple of days later the British battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse, which Churchill had sent to Malaya without any air cover, were sunk by Japanese planes and the writing was on the wall. The dominance of the Japanese by sea and air and their superior tactics on land made it plain that Singapore would soon fall, despite the fantastic claims by the British that it could be held.

By December 23, 1941, Australia’s official representative in Singapore, V.G. Bowden, was privately warning that “the deterioration in the Malayan defence is assuming landslide proportions . . . As things stand at present fall of Singapore is to my mind only a matter of weeks . . . The plain fact is that without immediate air reinforcements Singapore must fall.”

“The plain fact is . . . Singapore must fall”

Reacting to this grim news, a furious Curtin threw tradition and practice to the winds and sent a telegram the same day to both Churchill and – most daringly, and in British eyes most impudently – US President Roosevelt: “It is very evident that in North Malaya Japanese have assumed control of air and sea. The small British Army there includes one Australian division, and we have sent three air squadrons. The army must be provided with air support, otherwise there will be repetition of Greece and Crete and Singapore will be grievously threatened . . . The reinforcements earmarked by United Kingdom for despatch seem to us to be utterly inadequate.”

Curtin demanded adequate support for the Australians in Malaya, telling the supreme Allied leaders that “We have three divisions in the Middle East. Our airmen are fighting in Britain, Middle East and training in Canada. We have sent great quantities supplies to Britain, Middle East and India. Our resources here are very limited indeed.” Days passed with no reply to this urgent plea.

Curtin, frustrated at Australia’s lack of direct access to the Allied high command when the country itself looked set to be in the Japanese firing line, seems to have been worried that the British might dictate a policy under which Australia would have been left to its own pitiful resources while the great powers focused all their attention on beating Germany. The dismal showing of the British in Singapore was an ominous portent. Australia’s best hope was to persuade the USA that it needed Australia as a base from which to prevent the Japanese from exploiting their newly won territories and to throw them back when American naval strength recovered from the blow of Pearl Harbour.

In his history-making address, first published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 26, Curtin told his allies that Australia would “refuse to accept the dictum that the Pacific struggle must be treated as a subordinate segment of the general conflict”.

“Australia asks for a concerted plan evoking the greatest strength at the democracies’ disposal, determined upon hurling Japan back. Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom. “We know the problems that the United Kingdom faces. We know the constant threat of invasion. We know the dangers of dispersal of strength. But we know, too, that Australia can go and Britain can still hold on. We are therefore determined that Australia shall not go, and we shall exert all our energies toward the shaping of a plan, with the United States as its keystone, which will give to our country some confidence of being able to hold out until the tide of battle swings against the enemy.”

Curtin’s address outraged many, even in Australia, who felt that Australia had no right to attempt to bypass Britain in major affairs. But in Britain many agreed with him.

“Australia shall not go”

In the British Parliament Sir Percy Harris agreed that Japan posed a grave threat to Australians and New Zealanders “who came to our help in our darkest hour.” “Mr Curtin spoke the mind of the Australian people. I am not surprised that the people of the dominions felt that they had had a raw deal.”

The London Standard wrote that “Australia is menaced as never before and the sudden appearance of the threat has provoked Mr Curtin to demand a larger voice for Australia in determination of strategy. Is this request so scandalous? Australia fought gallantly in Greece, Libya and Crete and therefore no-one has the right to accuse her of pursuing a policy of unthinking isolationism now that her own shores are threatened. She certainly has won on other battlefields the right to speak in strong accents about her own territory.”

As Curtin’s assertive words struck home, Australia’s status instantly changed from a lowly subordinate to something much closer to an equal with its great allies. On January 2, President Roosevelt finally replied to the urgent telegram Curtin had sent 10 days earlier, when he learned for sure that Singapore was probably doomed: “Mr Churchill and I have considered your message with urgency which situation clearly demands. The necessary steps are already under way for flight to Australia of effective air assistance which I hope will arrive in very near future. We are deeply conscious of the magnificent contribution which Australia has made and is making to common effort and need to replace strength which she has despatched to other theatres.” A week later Churchill cabled Curtin too, expressing sympathy with Australia’s position and hinting that America might be willing to send up to 50,000 troops to reinforce Australia.

Scarcely placated, Curtin harangued Churchill, reminding him in a secret cablegram on January 17 of Britain’s promises to make Singapore impregnable and telling him that Australia would not have committed so many troops elsewhere if it had not believed these promises.

In another of a flurry of secret cablegrams between Curtin and Churchill, the Australian PM told his British counterpart that “the Australian people, having volunteered for service overseas in large numbers, find it difficult to understand why they must wait so long for an improvement in the situation when irreparable damage may have been done to their power to resist.”

Curtin was already looking beyond Singapore, which he knew was doomed. He demanded modern fighter planes to fend off attacks on Australian soil and on Port Moresby, and he warned that Australia’s future security depended on the ability of the US Pacific Fleet to overcome its injuries and keep open the vital supply lines to America. Accurately predicting the importance of such critical actions as the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, Curtin warned that Australia’s future could hinge on a single naval action between Japan and the USA.

On January 26 Bowden, Australia’s man in Singapore, reported that the island would probably be under siege within a week. The pitiful level of resistance and the limited reinforcements sent by Britain prompted him to tell the Australian Government in a secret cablegram that he seriously questioned “whether from the outset of this campaign it really was the firm intention to hold Singapore”. By February 12 Bowden reported that: “Except as a fortress and battle field Singapore has ceased to function”.

The bad news was that tens of thousands of allied troops were swept into captivity and the way was clear for Japan to take the former Dutch colonies on what is now Indonesia.

The good news was that Australia had finally and unambiguously shaken off its illusory dependence on Britain and was fighting tooth and nail on the world stage to force the Allied high command to develop a Pacific strategy that included the determined defence of Australia and New Zealand.

The archive of documents from Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade used to prepare this post can be found here.