In my younger days I couldn’t find a reason to be interested in family history. I mean, I listened to the stories my parents and grandparents told about their early lives and usually found them interesting and often surprising, but the general idea of “family history” left me cold. That was, I think, mostly because a lot of people who talked to me about family history were eager for me to know that they were descended from some illustrious famous personage or a convict First-Fleeter and it was clear that I was supposed to be impressed.

The idea of ploughing through old documents and parish records in the hope of being able to bask in some gleam of glory from a long-dead ancestor seemed pointless and tedious to me. So, with that early prejudice on board, it was many years before I came to reconsider the topic. Now, although I will never be the person who keeps working back through generation after generation in search of my bloodlines, I admit I am a convert, willing to concede the real-world benefits of learning more about the forces that have shaped our families. In my family, for example, I’ve been obliged by some discoveries to re-evaluate my thoughts and feelings about some of my immediate ancestors and I feel I’ve gained a better understanding of the ways inter-generational trauma can affect the living.

It started with my mother. As a precocious youngster I was permitted by my grandmother to find and read my mother’s adoption certificate, and that of my mother’s sister. So I knew my mother was adopted and I knew her birth name was different from the name she grew up with. But it took a long time to understand some of the emotional detail that involved from my mother’s perspective. My mother found out she was adopted when she moved to a small country school and some of the kids there knew – either through the school or the church – and told her in a rather mean way that her mother was not her “real mother”. This forced my grandmother’s hand and my mother’s bitterness about not being told the truth earlier has been a harsh irritant in her life ever since. First she was angry with her mother for not telling her, then she felt guilty about being so angry for so long. And of course she always wondered about her birth mother and formed imagined pictures of what had happened and how she came to be put up for adoption.

Skeleton from the closet

Not until a decade after my grandmother died did my mother make a concerted effort – with my help – to find her birth mother. I recall the first meeting, which I attended, and I recall conflicting feelings on both sides. Although the meeting was cordial my mother was evidently disappointed. This was not a fantasy reunion where the birth mother weeps with joy and shares a story of how her baby was torn from her unwilling arms and how she had waited years for that lost child to find her way back. Instead it was a slightly shamefaced and embarrassed meeting at which my mother felt like a skeleton that had forced its way out of a cupboard to which it had long ago been consigned. She was met, it seemed, with a kind of rueful sense of resignation which was not entirely lacking in friendliness but which didn’t measure up to years of anticipation on my mother’s side. Importantly too, my mother’s questions about her “real” father were met with a stolid refusal to answer. It was made clear that the father’s identity would never be told – if indeed it was remembered.

There were more meetings but my mother soon lost interest. Years passed before I decided to delve more deeply into my mother’s family history, partly to get to the bottom of persistent stories of some Aboriginal blood in her lineage and partly to try to identify the mystery father. I discovered that my mother’s birth mother had been the youngest of nine daughters in a very working-class family whose breadwinner was a coal-trimmer in the Newcastle industrial suburb of Carrington. The mother’s heritage was Welsh, the father’s English. I found out that the mother had left her husband after daughter number nine was born, heading to a new life in Sydney with one or two of the older daughters. Some of the younger girls were left with the father – a situation that surprised me. The youngest girl – my mother’s mother, Jessie – appears to have had a relatively wild period in her life. I found a court record of her being charged for vagrancy and I noted that somebody had managed to stump up 10 pounds bail – a very large sum for the time. I found that she was 24 years old when she gave birth to my mother in 1940 – much older than my mother had long imagined.

Some time later Jessie married and had a family, but it seems plain enough that she wasn’t ready for a baby when my mother was born. It was actually very useful for my mother to learn all this and I feel it helped her re-evaluate some things in her own life. I think she began to understand that she had been extremely fortunate to have been handed to a couple who loved and cherished her and who – although poor – were able to care for her properly.

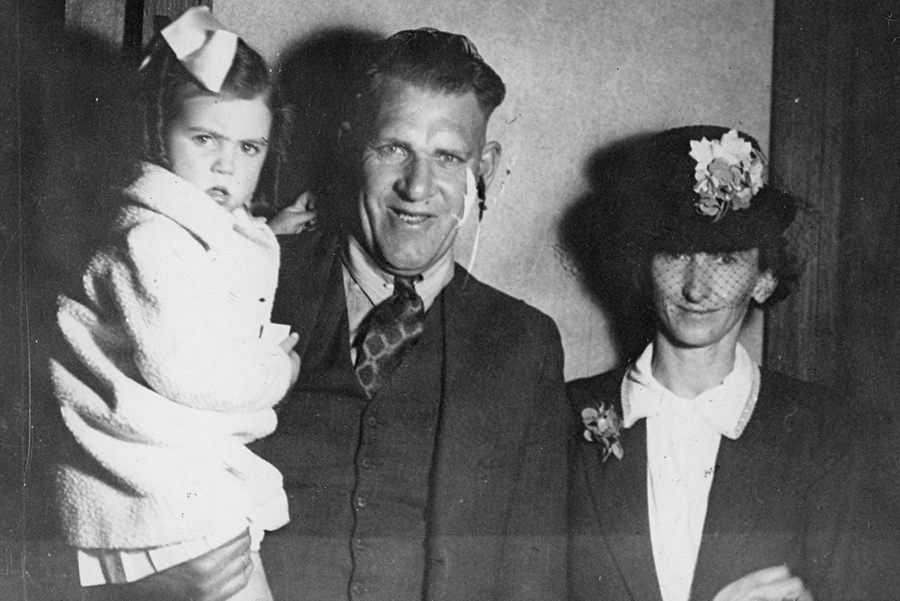

Mum’s adoptive mother – Lily – was also the youngest daughter of a big family. She was highly religious and strongly influenced by her Salvationist mother who survived two husbands and ended up living with Lily until her death. Lily’s life was also deeply affected by the loss of her favourite brother in World War 1. There is a story (unverified by me) that Lily had been jilted by a fiancee. She ended up marrying a wild country boy, Jack, who was part-Aboriginal and whose family had deep ties to the Dungog-Stroud area of NSW. It seems Lily couldn’t have children, for medical reasons, hence the adoption of two daughters. The family lived in Mayfield, Newcastle, until Jack lost his job at the abattoir (he stole an ox tail) and went back to Stroud to find work as a railway ganger, later bringing up the rest of the family once he found a job and place to live.

Jack had a series of strokes and ended up unable to work. Lily’s mother’s war pension – paid on account of her lost son – was a big factor in keeping the family afloat. But when her mother eventually died and the pension stopped, economic reality meant Lily, Jack and their daughters had to move back to Newcastle to stay with relatives until public housing became available. Tough times. Lily had a pension, and supplemented it by cleaning houses for “rich” people.

Knowing all this stuff helps me. It helps me better understand my mother and it also helps me appreciate my grandmother’s strength and compassion. Indeed, although I only had my grandmother until I was 12, I adored her. The same for Jack, although the aftermath of his strokes meant he couldn’t speak. He was a very warm and loving grandfather all the same.

Now that I think about my parents’ families I feel an immense respect for both my grandmothers. I can see that they were pillars of strength, buttressing their families in the face of many difficulties.

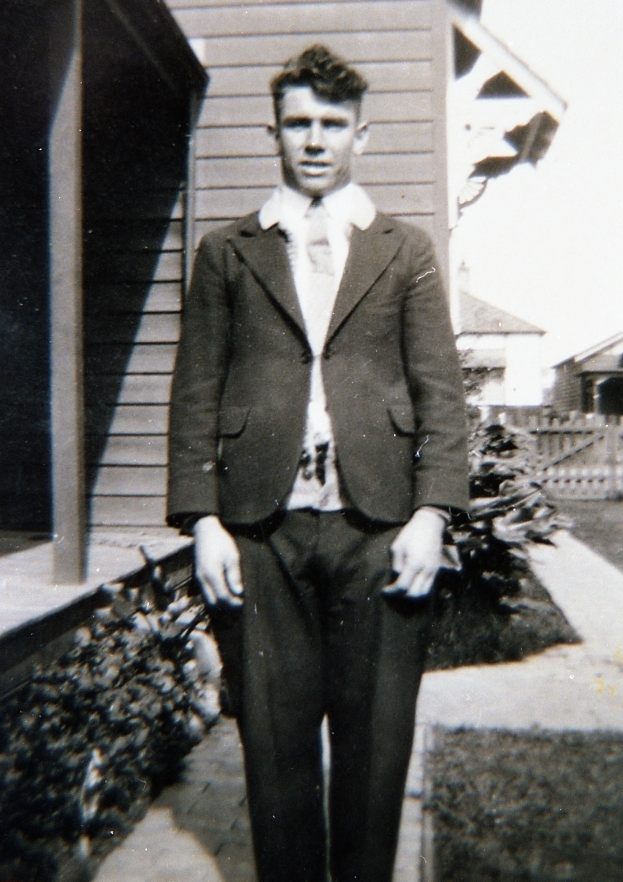

My father’s family was also poor, though not as poor as my mother’s. His father, Ernie, had been put into a boys’ home at Mittagong in his early teens when his own father, returning from World War 1, found his marriage at an end. Both my father’s father and his grandfather were “wild” men, perhaps typical of many of their time. Hard drinkers, pub brawlers and unskilled from a work point of view. Ernie’s dad worked as a coalminer and, later, a gardener. Ernie had many jobs including as a miner in a number of pits in the Newcastle area. He had a name as a formidable fist-fighter and was a passionate punter. Having never really been close to my grandfather, I now have empathy for his ordeal. The boys’ home can’t have been ideal. Ernie married Hazel, who had come from a relatively well-off family whose situation was catastrophically affected when her father was killed in a railway shunting accident. He had been a cabinet-maker at Narrandera, but was forced to move to Newcastle for other work during the Depression. Hazel was working in a shop at Mayfield when she met and married Ernie.

Like his father before him, Ernie went to war. His experience of the war against the Japanese in New Guinea evidently scarred him. Hazel, at home with the three children, struggled to make ends meet. Fortunately she was extremely resourceful and hard-working. She had to put up with a lot, especially after Ernie came home from the war. My father recalls episodes of drunken violence that forced Hazel to hide under her son’s bed in the closed-in back verandah. I’m not aware of Hazel ever complaining – not that I would know. I’m sure the relationship had its good points too. Hazel was a stoic. She also blossomed in later life after Ernie died, learning to drive, playing bowls and taking coach trips around Australia with other older women. Not overtly warm and loving like my other grandmother, I nevertheless came to admire Hazel for her strength and endurance.

In family history there are always loose ends. I would like to know more about why my father’s ancestor James Ray left Ireland and came to Australia, for example. I’d like to know a little of his background in Ireland. That’s research for another day.

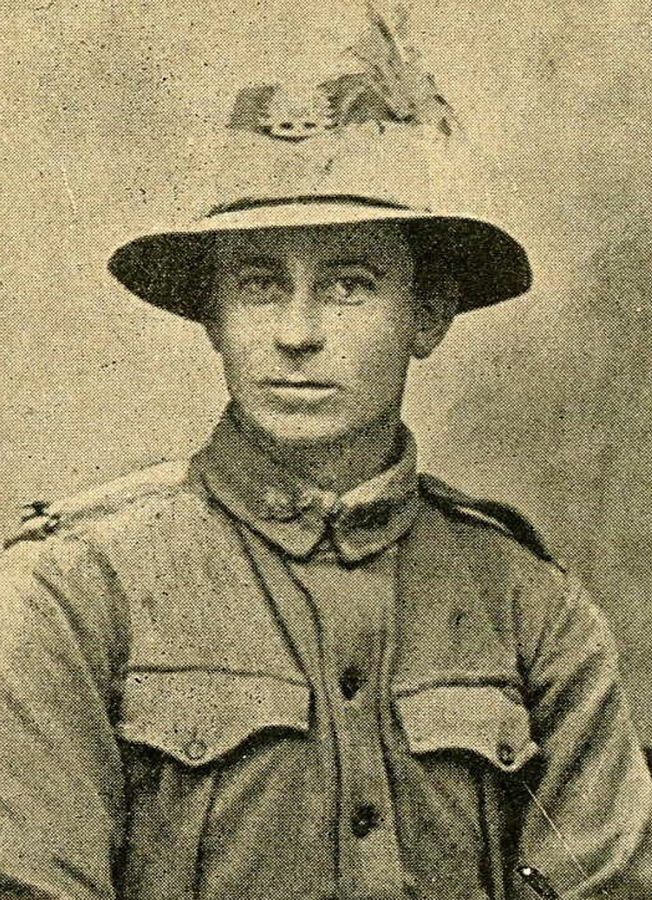

The other serious loose end, now somewhat teased out, was the question of my mother’s biological father. Given that her birth-mother had gone to the grave without revealing his identity, it was clear that the only possible path to knowledge was a DNA test. After some consideration my mother agreed to this, and the result was impressive. Matching with the DNA of other people already available for viewing online led to the conclusion that only two men – brothers, of course – were possible candidates. One of those men, Bertram, had been living in Carrington in 1940, the place and year of my mother’s conception. He was a World War 1 veteran, much older than my mother’s mother, and also apparently a rather busy chap when it came to the ladies. I suspect I won’t ever learn much more about him, but I don’t really need to. It hasn’t meant much to my mother, but at least this discovery has laid to rest darker fears I had harboured about my mother’s conception.

This background knowledge of my grandparents’ lives has been very valuable to me. It has helped me better understand my parents and has added perspectives to my understanding of my self. I haven’t found aristocrats in my tree and I’m not looking for any. I’ve found convicts, working poor and Indigenous people (through adoption). Literal foot-soldiers in the system, picked up and dropped at the whim of the wheels of state, living their lives as best they could through whirlwinds of war, depression and personal calamity. I own them and they own me. My people, my roots and my self.