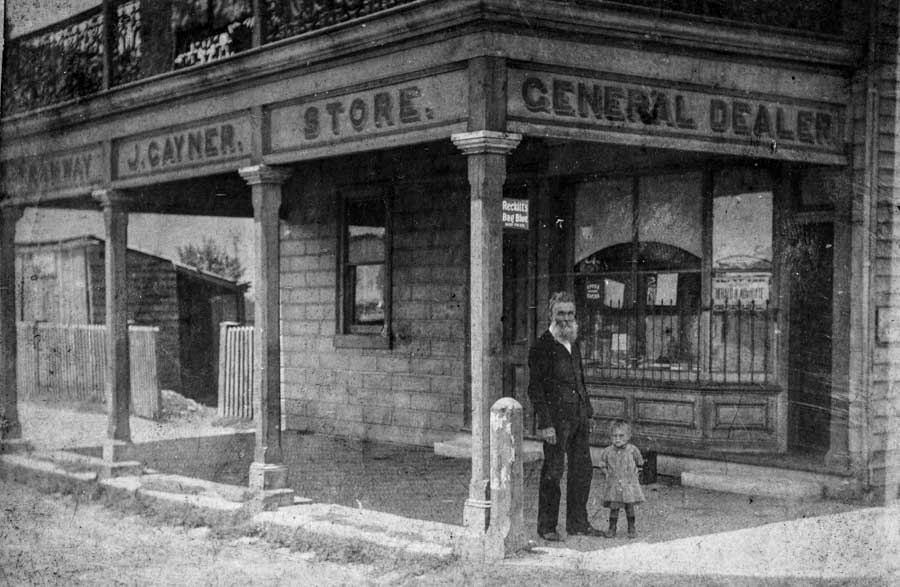

In the photo above, the bearded gent is James Gayner, with his son Mathew, (born in 1875 and then aged about three), outside the family’s general store and paper shop in Tudor Street, Hamilton. The family had the store for 83 years and members covered hundreds of thousands of kilometres on foot, delivering papers to their customers.

James Gayner and his wife came from England in 1857, chasing work in Newcastle’s coalmines. He started work at the Australian Agricultural Company’s Borehole pit in Hamilton, later transferring to the Lambton pit where he worked until injury forced him out. It was then that he opened a small grocery store in Tudor Street and got the agency to deliver the Newcastle Chronicle – a forerunner to The Newcastle Morning Herald.

The Gayners had seven sons and three daughters, all of whom worked for at least some time in the store and newsagency. Little Mathew from the photo above started hand-delivering papers at the age of 11, and he offered some interesting recollections in a newspaper interview at the time of his retirement in the 1960s at the age of 81. He said that at the time he began, Hamilton was divided into three distinct areas: Borehole (Camerons Hill area), Pit Town (Beaumont Street to Swan Street) and Happy Flat (from Steel Street to Turner Street).

“The papers were distributed from Newcastle by a man named Buchanan, who was assisted by his son. He used a two-horse van and after delivering our papers at 4am – he threw them on the verandah and woke everybody up – he would go on to Broadmeadow, through Lambton to Wallsend, arriving there about 5am. Some would then be taken on to Minmi,” Mr Gayner told reporter Les Madden.

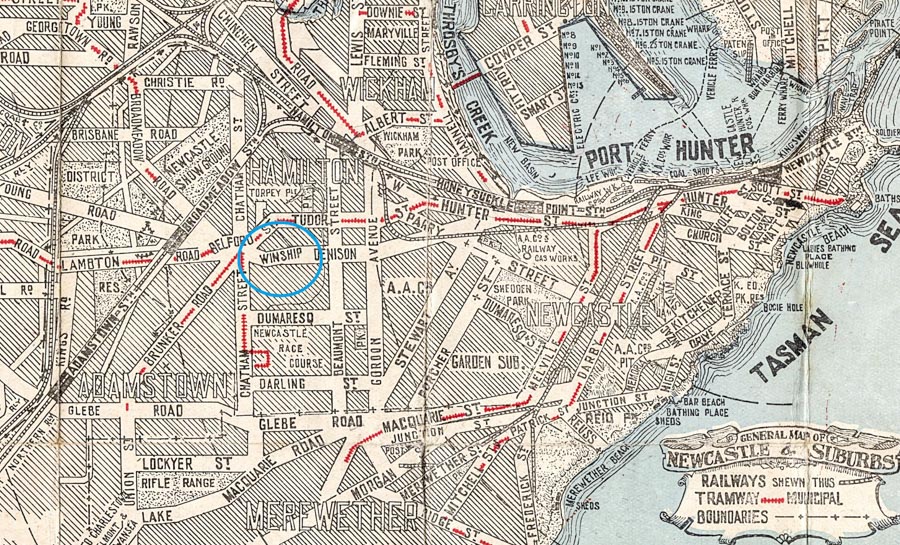

Mathew’s deliveries began at Webster Street then on to Turner Street, then to Reay’s Turkish Baths in Denison Street, then to the home of the under-manager of the Borehole No 2 pit, who lived beside the coal railway line in a house named Spinnamore Cottage. The pit, he said, was close to the latter-day location of Tom Maguire’s gymnasium, more or less Birdwood Park.

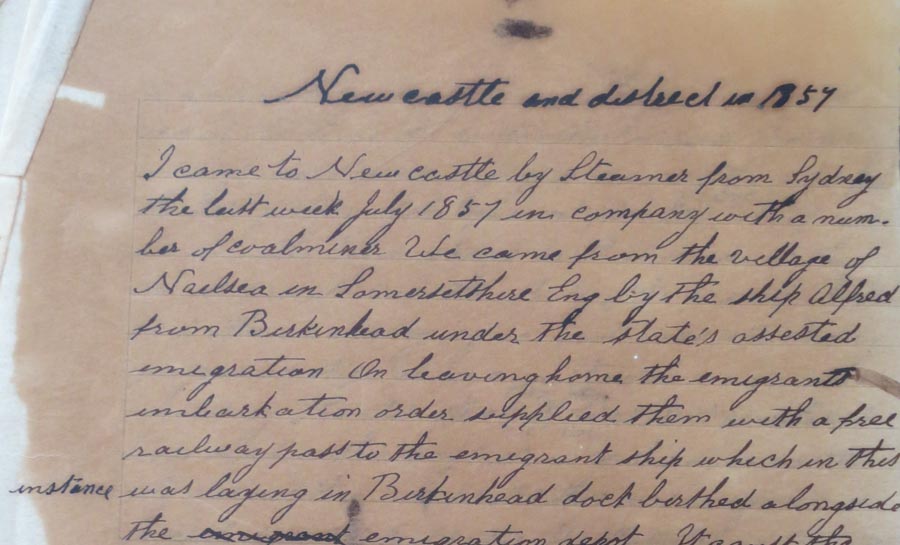

Mathew’s grandson Al shared with me a document handwritten by his great-grandfather, James, in about 1910. The document relates some of James’ recollections of Newcastle when he arrived in the city many years before. Below is a transcript of the document.

Newcastle in 1857

I came to Newcastle by steamer from Sydney the last week July 1857 in company with a number of coalminers. We came from the village of Nailsea in Somersetshire England by the ship Alfred from Birkenhead under the state’s assisted emigration. On leaving home the emigrants’ embarkation order supplied them with a free railway pass to the emigrant ship which in this instance was lying in Birkenhead Dock berthed alongside the emigration depot. It cost the adult emigrant one pound, children were charged according to age: those at 17 years were classed with the adults. We left Birkenhead April 20th 1857 and arrived in Sydney the last week of July and came to Newcastle the next day. Although 60 years have elapsed since I came I have a lively recollection of the connecting circumstances of Newcastle and district at the time of my arrival.

I recollect the steamer berthed as close to the wharf as circumstances admitted of but as the wharf consisted only of ship ballast the steamer could not berth close to the landing place, consequently it required a pretty long gangboard to land the passengers and cargo ashore. I observed at the time the contractors Messrs Brooks and Gooders were engaged driving the piles for the first portion of the present planked wharf and six months later ships berthed alongside as they do at present and the whole of the present wharf and other necessary requirements were effected by progressive steps as circumstances rendered necessary. Hunter Street , then off Watt Street, consisted of loose sand with a dray track on each side and as the city was not then incorporated there was an absence of properly defined footpaths. The hospital and post office were two wood cottages. The hospital had no resident M. doctor or professional nurse. The late Dr Bowker and the late Dr Stacey were the only two M doctors for Newcastle and district. There were a male and female attendant at the hospital who acted according to the instructions of the doctor who sent the patients to the hospital. Those in the present who recollect the old institution referred to will be much in touch with the proverb “Angels visit few and far between”. Newcastle in 1857 was little more than a coal shipping depot. Rodgers foundry in the present is of much more importance than it was then.

The Australian Agricultural Company then had three pits officially named D, E and F. D and E were usually termed the old and new borehole pits. The D and E pits were situated on what is now named Winship Street but at the time referred to was termed the Borehole Hill and the F Pit was situated on the hillside in Newcastle and was last used as the upcast shaft for ventilating the Sea Pit workings.

What is now Winship Street was then Borehole Hill which consisted of bark-roofed slab huts. The only brick building on the hill was known as Jimmy Lindsay’s house on the opposite side to Cameron’s Hotel. The Hotel was built in 1858. Apart from the AA Company’s three pits the next of importance was the Coal and Copper Company’s Victoria Tunnel situated in the Glebe hills in the present Municipality of Merewether. Apart from these two principal sources of supply there were three other smaller collieries known as Jimmy Brown’s, Donison’s and Nott’s, situated in the Glebe hillside. The whole of the coal companies at the time referred to used two-ton wagons and with the exception of the AA Company wood rails . . . were used with horse traction.

The AA Company’s first loco engine was put on the rails five weeks after my arrival. The whole of the collieries referred to in what was then known as The Glebe Junction on the Victoria Tunnel line in the vicinity of the pottery works which was usually referred to as the Junction and which is the most important ward in the present Municipality of Merewether. When the Coal and Copper Co laid the rails for their first locomotive, “The Black Demon” the small collieries referred to closed down.