Kooragang Island is a name with little romance for most people in Newcastle, NSW. The name connotes a polluted wasteland near the mouth of the Hunter River, permeated by the toxic legacy of generations of heavy industry. But things weren’t always like that.

Before white settlement there were several islands in the Hunter River estuary, forming a jigsaw of shapes cut and criss-crossed by creeks and tidal channels. The wetlands and mudflats were a prolific breeding ground for marine life and a feeding ground for local and migratory birds. The Aboriginal people hunted there and found plenty to satisfy their needs.

When white people came they gave the islands new names. Dempsey Island. The Spectacle Islands. Goat Island. Upper and Lower Moscheto Islands. Spit Island. Table Island. Snapper Island. Mangrove Island. And glorious Ash Island, a densely forested wonderland that left early Europeans in breathless awe of its sylvan beauty. Walsh Island, home to Newcastle’s first state dockyard, was reclaimed from mud flats and the low-lying Spectacle Islands.

The main islands, largely stripped of their trees, became home to productive farms before these too gave way before the onrush of heavy industry. Well into the 1930s and 1940s farming families flourished on the rich soil of the islands, punting their produce across the river to Newcastle. Ash Island had its own school.

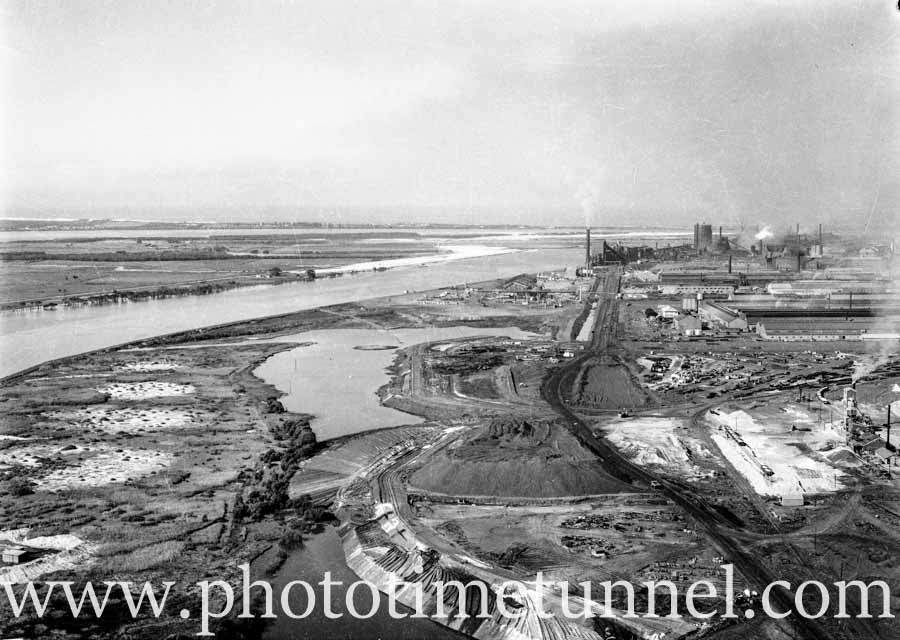

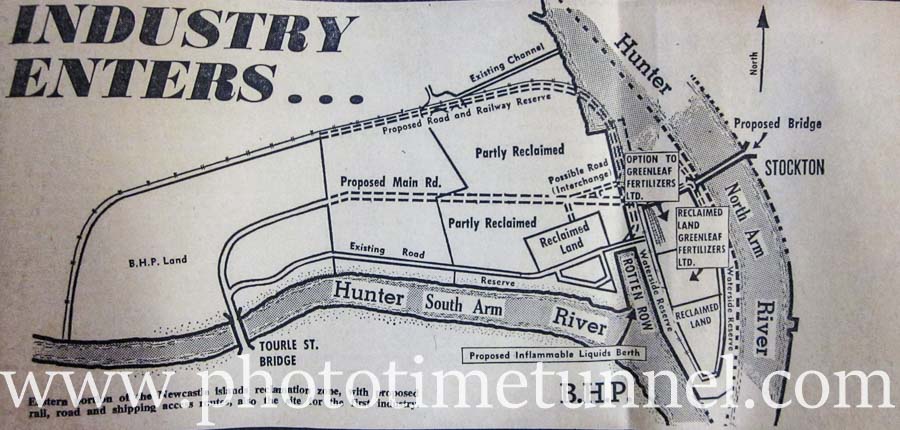

Spit Island was lost when Platts Channel was filled, giving the steel-related industries more land. And the government, with visions of an ever-expanding industrial colossus on the Hunter, used dredging spoils and industrial waste to fill in the creeks and wetlands to make the giant Kooragang Island, whose name is supposed to be an Aboriginal word meaning ‘‘place where birds gather’’.

The grand industrial vision was never completely fulfilled, but the islands have nevertheless changed forever. Today, patient and persistent volunteers are doing their best to restore Ash Island, at least, to some semblance of its former natural glory.

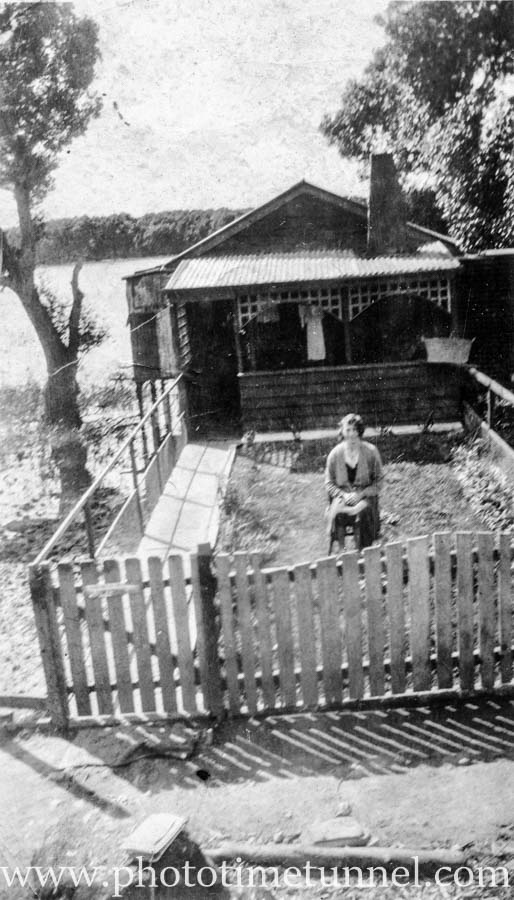

Some years ago I met Ted Bartlett, who was living at Sandgate. He told me how, when he was about four years old, his family moved to live near the river. The Great Depression forced hundreds of other Hunter families, who could no longer afford to pay rent or rates, into makeshift homes wherever they could find undisputed space. Camps of huts built of whitewashed hessian, and tin sheets flattened from kerosene cans, sprang up on the outskirts of the towns. For the Bartletts and several other families, home in the tough years became a straggling line of about 28 “boat sheds” built over the mud flats alongside the Hunter River below Mayfield. The huts were built in the limbo land between the tidemarks, and the family paid a peppercorn rental of 10 shillings a year to the Australian Agricultural Company.

United by economic hardship, this little community fared better than many others, thanks in part to the prolific produce of the river. The Hunter’s intricate estuary of channels, wetlands and islands wove its way into the young Ted Bartlett’s heart, triggering a love affair that lasted the rest of his long life.

Since his family made its enforced river change in the hungry 1930s, Ted Bartlett never lived more than a kilometre from the Hunter’s banks. When I met them, he and his wife Margaret (whom he introduced to me as “the leader of the opposition”), were still living close to the river in a house he built himself – partly from material salvaged from shipwrecks in the estuary.

Margaret had also spent some of her early years in one of the boatsheds, where her family shifted from Georgetown when work dried up for her transport contractor father. “My father’s horse and dray pulled some of the stones that built St Andrew’s church,” Margaret told me. Margaret was a schoolgirl when her family moved to the boatshed, and she didn’t really appreciate the change; unlike her mother, who loved the river and would sit on the jetty catching fish. She would catch bream and also crabs in a wire trap using bits of broken pottery as “bait”, and sometimes she would net lost clothes pegs from the water with a scoop. Margaret’s family, the McKinnons, had one of the best boat sheds. It was big, with double doors that could open to the river, and it had a good wooden floor that made it ideal for community dance evenings, when a gramophone borrowed from Newcastle dance teacher Bert Caldwell used to grind out tunes while the mullet jumped outside.

The McKinnon residence was also renowned for its running water. A savvy tradesman had plumbed the building from a water main that crossed the river nearby, freeing the family from the long walks for water that other river families endured when their tanks ran dry.

Burning cowpats to ward off mosquitoes

Living on the river may have been an ordeal for some, with the mosquitoes in summer and the cold chill in winter, but a boy bred in the Depression could shrug these things off. Ted recalled his father used to keep the mosquitoes at bay by burning lumps of dried cow manure in the boatshed. Ted used to share the back room – an enclosed verandah – with his brother, Cliff, while his parents used the main room inside. On cold nights, Ted said, his parents got the combustion stove fired up. “Dad used to sit on a chair with his socked feet on the grate and Mum stood with her back to the stove and her skirt hitched up. We boys made do the best we could,” he told me.

Ted’s father got work wherever he could, supplementing the family income in a variety of ways. He tanned skins and sold them, the whole family helping to clean the hides on the table at night. If somebody in the family caught an especially good fish, he might raffle it at Amos’s hotel in Mayfield. And he’d do soldering repairs on the watering cans used by the Chinese market gardeners who grew lush produce on a bend in the river, just upstream.

“I used to go up the gardens with a sixpence from Mum to buy a soup-bunch. You never saw vegetables like the ones they grew there. The cook, who spoke the best English, used to see me coming and get a bunch for me,” Ted said. “He’d take my coin, then say he was going to get my change. He’d go to the hut in the middle and come back a minute later and just give my coin back.”

Oysters as big as saucers on decaying old shipwrecks

Fishing was a constant pastime for many people, and in the days before the river was too polluted it yielded huge quantities of delicious food. Ted knew where to row his boat for the best bites, netting mullet in the mouths of the narrow creeks, catching big green crabs, filling tins with prawns and hooking fat bream at the turn of the tide. Ted knew “Rotten Row”, where hulks of old ships lay, decaying, and a place called “the Dead End” where he climbed around old wrecks and prised off oysters “as big as saucers”.

Ted’s memory was full of anecdotes of his riverine neighbourhood. Like the time one neighbour grew tired of owning a dog that had turned vicious and started biting children. “My father agreed to shoot the dog and all the people from the boat sheds came out to watch. The dog’s owner threw a stick into the river and when the dog went to fetch it, my father shot it. He’d only just fired when a huge fin appeared and the dog disappeared completely. All that was left was a red stain on the water that just drifted downstream and dispersed.

The Hunter estuary has changed beyond recognition since Ted Bartlett punted his boat around its shallows, hunting fish and salvage in the salty swamps. The boatsheds in which the Bartletts and other river families lived, stood on stilts above the mud flats on Platts Channel, opposite Spit Island.

Both these major features of the old river have disappeared. Creeping industrialisation and massive land reclamation projects – culminating in the creation of Kooragang Island – led to the filling in of Platts Channel. What used to be Spit Island became just another piece of dreary industrial foreshore and the exiting point for the Tourle Street bridge. Vast tonnages of industrial waste and dredging spoils were used to fill in the web-like creeks and channels that once separated the islands.

One of Ted Bartlett’s final fond memories of Platts was when the channel was closed at both ends, with just enough tidal exchange to feed the fish and other creatures trapped inside. “The prawns grew huge, and I filled tin after tin with them and sold them at work, and the mullet were massive too,” he said. But the secret got out and a trawlerman cleaned up the trapped harvest. Not long after, the island and the channel vanished forever. All across the estuary, the same thing was happening as old islands with old names disappeared from maps and memory.

Fishing and farming displaced by industry

As heavy industry steadily took over the estuary, nature, fishing and farming had to make way. Industrialisation of the Hunter River islands started relatively early after white settlement. Walsh Island was built up out of the mud with stone quarried from beside the river upstream of Port Waratah, and with mud and silt dredged from the harbour bed. It supported the lost and often forgotten industrial giant that was the Walsh Island dockyard.

This extraordinary behemoth of government enterprise built and repaired ships, made bridges and railway carriages, and manufactured munitions used in World War I. Like most government enterprises, Walsh Island was subject to fierce ideological argument between capitalists and socialists and it was, eventually, shut and dismantled just before the outbreak of World War II.

But the BHP steelworks, established in 1915, grew massively, bringing jobs and prosperity to Newcastle, but leaving a legacy of pollution and a dramatically altered river. BHP and its satellites spread along the river’s edge, using the Hunter as a drain and using their waste products as fill to reclaim more land for their growth.

The government project to join the Hunter River islands and turn them into one big industrial estate was a natural extension of the view that Newcastle’s only future lay in heavy manufacturing.

Ted wound up working for BHP, testing the water, and he knew many secrets. “The industries used to release their pollution on the incoming tide,” he said, and he noted that the advent of the Courtaulds rayon factory at Tomago had a drastic effect on fish in the river.

Ted and Margaret passed away not long after I spoke to them. I’m sorry to say they took many more stories with them than the few I was lucky enough to hear.

For another post about a different Depression settlement, click here.