The main fighting Maud Butler did in World War I was with the authorities who wouldn’t let her go to the front to “do her bit”. A feisty Kurri Kurri teenager, Maud stowed away twice on troopships – having first disguised herself as a boy – and later got in trouble for collecting donations in uniform on a wartime Anzac Day.

Stowaways were not rare. Digger diaries refer to stowaways being caught after troopships had sailed and being taken on strength and posted to battalions. But only if they were male. Maud Butler claimed at the time of her first stowaway attempt that she was 18, but she was almost certainly younger and was probably no older than 16. It appears she had left her home in Kurri Kurri some time before (she claimed to have left at age 14) and she said she had worked as a waitress in a variety of places before her last known position at Pyrmont in Sydney.

It isn’t clear why Maud wanted so badly to go overseas. She mostly told those who asked that she wanted to contribute to Australia’s war effort. It was reported that she’d tried to join the Red Cross as a nurse but had been turned down because of her age and inexperience. Her first attempt to stow away was around Christmas 1915, when patriotic fervour over the Gallipoli campaign was still strong – although by then the troops had been withdrawn and the campaign declared a failure. Maud was quickly discovered and shipped back to Melbourne. According to her personal statement on file in the National Archive, dated December 25, 1915:

My name is Maud Butler and I am 18 years of age. My father’s name is Thomas Butler and he resides at Kurri Kurri NSW. I left my home when about 14 years of age and have been employed as a waitress in different places in Sydney. My last place was with Mr R Stewart Union St Pyrmont. I left there on Wednesday last and purchased a suit of uniform from a soldier and had my hair cut in male style. On the night of the 22nd inst I boarded the Suevic by a gangway which was not watched by the sentries and secreted myself in a boat on the boat deck. On the morning of the 24th Inst a parade of soldiers was held on the boat deck when I was discovered and I admitted to the doctor that I was a girl. My object in stowing away was to get to Egypt to join my brother Maitland Butler of the 19th Battalion. I did not think of the seriousness of the offence until I was transferred on to the SS Achilles. I would like to be allowed to go back to Sydney.

“I admitted to the doctor that I was a girl”

The official file states that “the captain of the ship ventured the opinion that she was of good moral character but was venturesome and had a very strong will”. Maud strongly opposed the suggestion that she be sent to a convent and she returned to Sydney on a train on December 28. Maud’s story about wanting to join her brother Maitland was almost certainly false. After all, Maitland was not much older than Maud and official records show he didn’t enlist until 1917. But Maitland’s record suggests he might not have always been a reliable witness, and he might perhaps have told Maud that he’d joined up earlier than he did. In an interview with the Melbourne Weekly Times, Maud insisted that her brother had been at the front for six months before she stowed away, but that seeing him wasn’t her main reason for wanting to get to the war.

She said she had: a desire to help in the war in any way I could. I read a good deal about it, of course, and I thought that if I got to Egypt the Red Cross people there would be only too glad to get me and to let me do my bit. I read how much overworked they all were. As time went on I got more and more unwilling to wait, so I went down to see a transport that was lying in Woolloomooloo Bay.

Maud had already acquired her uniform (all except the regulation tan boots) and now got her hair cut short, soldier-style, before coming back to the ship at night to try to get aboard. She claimed she climbed a rope from the wharf to the ship’s bow while a sentry wasn’t watching, and then climbed into a lifeboat to spend her first night aboard. According to the newspaper report, “the next day she mingled with the soldiers on the ship, watched them playing cards and at their games on the deck”.

“Only one thing was amiss. There was no seat for her at mess, and a very hungry girl indeed it was who crept that night into her hiding place.”

The next day she was asked to show her identity disc and, being unable to do so, was taken for questioning. Exposed as a stowaway, she at first managed to conceal her gender and claimed she was told it might still be possible for her to continue to the front, pending a medical examination. Maud knew then the game was up and confessed she was a girl. The captain “was very nice and kind”.

He pretended to scold, but said he would have taken me on if the secret could have been kept. But it was all over the ship in a minute. The first thing he did was order me some breakfast. They put me in a guardroom with a soldier on guard. When the captain sighted a ship and told me I was to be transhipped to Melbourne I broke down and cried.

The incident was reported in the troopship’s onboard newspaper:

A muster parade had been called, and the adjutant was gently floating round the ship looking for shirkers. Presently his eagle eye glared on a young private, and he asked, ‘Well, my lad, why aren’t you parading with your unit?’ The lad stammered and replied, ‘Sir, I cannot find my unit.’ ‘Probably not,’ said the adjutant, whose searching glare had disclosed the fact that the offender’s trilbies were not encased in service boots, while the jacket was minus battalion numbers. After a back view he said in his dry and official manner, ‘You are a stowaway, and it will be necessary for you to be examined by the medical officer.’ Exit soldier and adjutant. It was afterwards announced that the soldier was a dear little girl. The wireless got to work, and Maud was sent back to Melbourne. She was still dressed in khaki, but carried in addition a cash belt containing £23, generously subscribed by all on board, so that on her arrival in Melbourne she could secure the necessary raiment to enable her to resume her proper station in life.

A forged ID and a pistol

Back in Melbourne via the SS Achilles, Maud baffled the authorities who admired her pluck. They let her go, assuming she’d learnt her lesson. But Maud was definitely “strong-willed” and within a few months she tried again. It was late on Tuesday, March 7, 1916, when Maud – back in uniform and this time under an assumed name and with a forged identification disc and a pistol – followed some drunken soldiers in a staggering procession onto the ship after their last shore leave. She had noted that the sentries had grown tired of checking every drunk that came aboard and simply pretended to be among the rowdy group.

This time I made no mistake. I got military boots and made an identification disc, which I stamped “No.4850. Pte. Harry Denton, 15th. Battalion, 3rd Infantry Brigade, Australia.” Then I waited my chance.

She hid away overnight but was discovered next day when an officer checked her identification against the ship’s documents. She was handed over to the Water Police and formally charged. Maud pleaded guilty to all charges and promised that, if she was given a chance, she would give up trying to go away to the war. She undertook to return home. The magistrate sentenced her “to the rising of the court” and ordered her to return the uniform to the military authorities, and the revolver to the police. Outside the court Maud remarked:

The military people have not given me permission to go and do what I can to help our boys, although I am tired of asking. There was nothing for it but to stow away and try to bluff through.

Maud had promised to stop trying to get to the war, but her fascination with the khaki uniform had not abated, nor had her determination to help the war effort. Weeks later she was in trouble again, this time for collecting donations in Sydney on Anzac Day whilst wearing a soldier’s uniform. Military police spotted her and, thinking she was a boy, asked what unit she belonged to. When the truth emerged she was marched off and hauled into court. It turned out that she had approached the Returned Soldiers and Sailors Imperial League in Newcastle with an offer to help in any way she could. She was put to work collecting funds for the 35th Battalion Fund at an Easter Monday surf club carnival. She wore a uniform whilst collecting and raised something less than £20. The presiding magistrate sided with Maud, saying he thought it “rather a pity she is here at all” and fining her a nominal shilling before letting her go free. Maud did, however, have to promise never to appear in the uniform again.

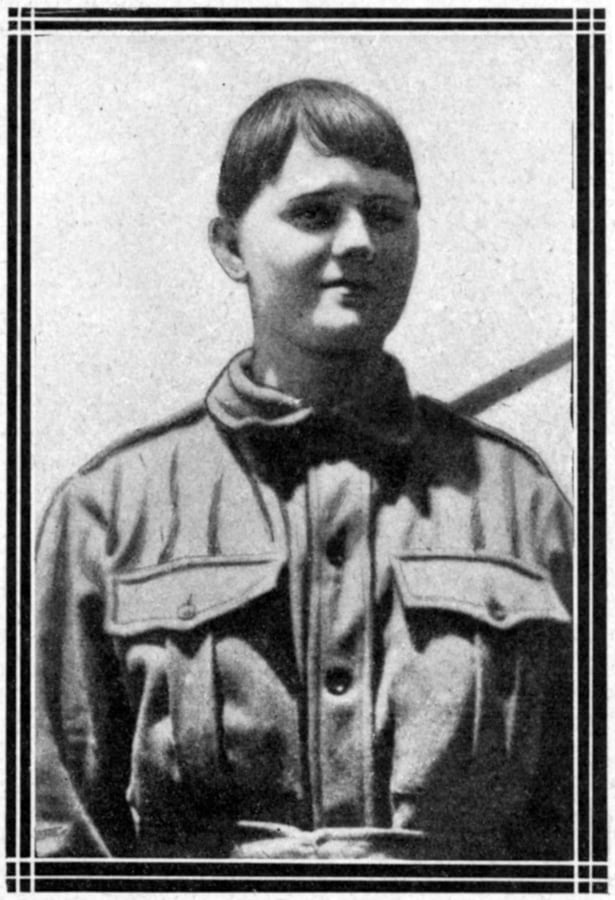

Maud dropped from sight for the rest of the war but appeared in the sensationalist journal the Truth in 1930 with a simple retelling of her stowaway story. By then, the paper reported, she was “a slim, little grey-eyed woman, with two boys and a little girl, the last 18 months old”. The Truth published this photo of Maud, as she reportedly appeared in 1930.

But what of Maud’s brother, Maitland Butler, whom Maud supposed to have been at the front since 1915? Official records held by the National Archives show that Maitland tried to enlist in April 1917, claiming he was 21 years old and a coalmining wheeler by trade. His mother protested and signed a statutory declaration that he was only 18 and insisting he not be permitted to enlist. He was discharged in line with his mother’s wishes. But in September 1917 Maitland Butler enlisted again, this time under the false name “Frank Emerson”, now claiming he was 20 years old. He was accepted and sent overseas.

Her brother Maitland was a bad soldier

Maitland had a chequered military career, being penalised more than once whilst in England for going absent without leave. He got to France in July 1918, just in time to be badly gassed. It appears his gas injuries may not have been as severe as his dose of gonorrhoea, which required considerable medical attention before the war ended and he was sent home via South Africa on the troopship Euripides.

Maitland went AWL again at Durban and missed the sailing of his ship. He was arrested and charged with gambling before escaping from custody. Caught again, he was sent under arrest to Capetown and arrived back in Australia in December 1919.