My family has been talking, recently, about mementos. Specifically, what mementos will my children have of their grandparents?

As I know from experience, the most significant and enduring mementos are those of attachment, emotion and sentiment, forged in the relationships between people. But it’s nice, too, to have at least one or two physical reminders of the people we have known and loved.

Of my four grandparents, the one to whom I was closest as a child was my maternal grandmother, Lily Jane Pritchell, nee Allsopp. Interestingly, she was not a blood relation. She and her husband Jack adopted my mother and my aunty because they could not have children of their own. I have learned that a person’s grandchildren see them very differently from the way their own children do. The relationship is very different. Hence I see my grandmother with a rosy glow that my own mother can’t know, since she knew her mother over a longer period and through different experiences. When my mother tells me things about my grandmother such as, for example, she was bad at budgeting and often had to borrow money, or that she could be a rather stern disciplinarian, these ideas are strange to me. To my childish eyes my grandmother was an angel who had no faults. She had been the youngest in a biggish family, had nursed her mother into very ripe old age and nursed her husband when he in turn suffered a series of severe strokes. She idolized my mother and she made me feel like the most special child in the world, wanting to spend time with me and happy to have me stay with her. The memento I love most from her is a piece of glassy quartz which she always had on display on her mantelpiece. It came, she said, from Glenn Innes, NSW, where her family had spent much time. There had once been another piece, with a green crystal inside it, but this had gone to somebody else in her extended family long before. Her piece of quartz was a treasure to her, and I loved it too. When she died – I was aged 12 – nobody objected to it being passed to me.

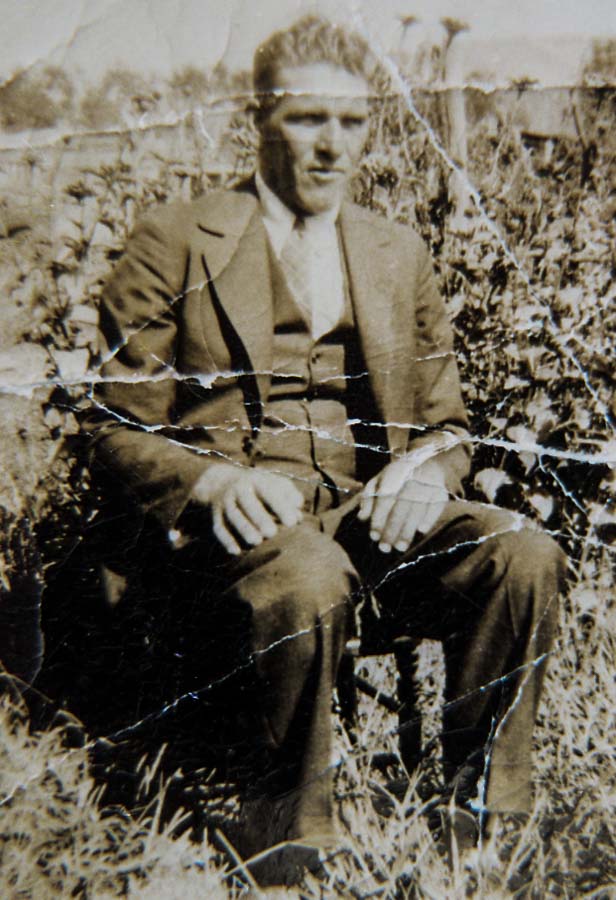

My maternal grandfather, Jack Kenneth Pritchell, had – as I wrote above – suffered some severe strokes before I met him. As a result he could not speak, other than a few expressions which he used to suit most occasions. “By Geez!”, “I’ll say!”, “Bloody rot!” were the commonest I recall. He could read the paper, mostly the death and funeral notices, and point out the people he had known. He gardened a little, and sometimes “repaired” things, always using his scant bushman’s toolbox of pliers, an old hammer, a big old screwdriver, rusty old three-inch nails and thick fencing wire. He chain-smoked roll-your-own cigarettes and his fingers – as fat as sausages, it seemed to me – were consequently yellowed. He was very affectionate and caring towards me and I well recall sitting on his knee on the old chair on the front patio of my grandparents’ Housing Commission fibro at Glendale, NSW. In recent times I have learned that he was part-Aboriginal and that his family was very well-known in the Dungog area in years gone by. My chief memento of “Pop Pritchell” is his battered old shaving mug.

My paternal grandmother, Hazel Rose Ray, nee Whittaker, was a true stoic. As a child I was not close to my paternal grandparents. The relationship between them and my parents was strained, and although we often visited there was little affection shown. Nanna Ray would cook us a baked dinner in her kitchen that had no hot running water. In common with my other grandmother, she had a disused wood-fired oven, superseded by an electric range. I recall her cupboards were stocked with neatly folded used paper bags, bags of foil milk bottle tops, pieces of string and even toothpaste tube lids. Having lived through the Great Depression, she was frugal to a high degree and hated to throw anything away. I grew to know my grandmother better after my grandfather died. She finally learned to drive, started going on bus trips to see Australia and began to soften as a person. I would visit her quite often and I remember once giving her a hug near her back door. She hugged me back, tightly, and said: “It’s so good to have a hug”. I realised then how alone she was. In later years I discovered something of her past, learning how her father, a cabinet-maker, had moved with his family from Narrandera at the start of the Depression, got a job with the railways and then been killed in a shunting accident. His bereaved family was plunged into instant poverty. When I was a small child I would always be drawn to the glass-fronted china cabinet in Nanna’s lounge-room, and chief among the interesting things in it I admired the cheap little pewter horse. Nanna gave this to me before she died, knowing how much I had always liked it.

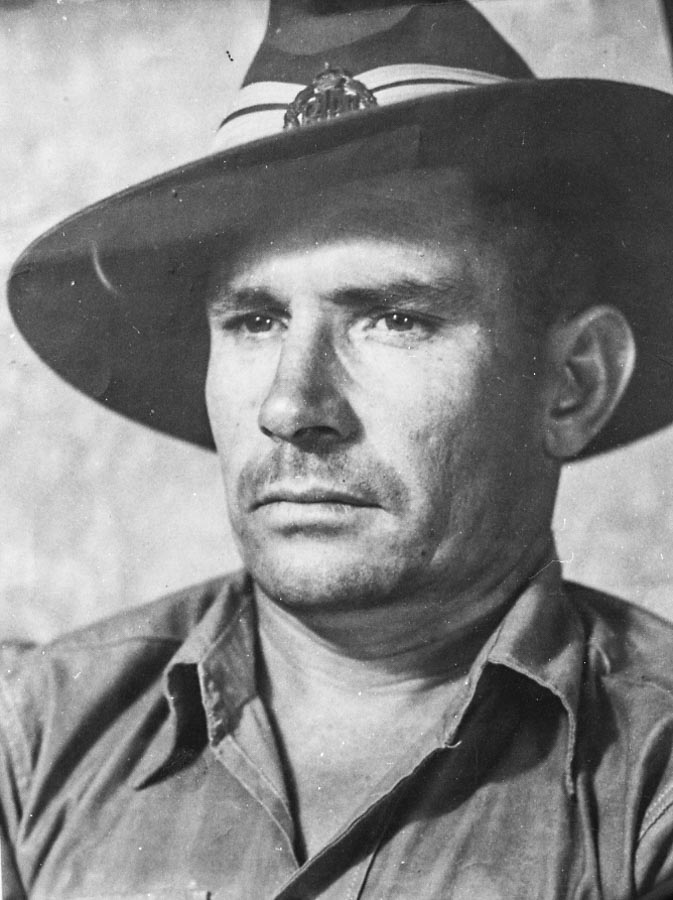

My paternal grandfather, Ernie Ray, was a complicated and difficult character. As a child I found him rather forbidding, although he was more jovial than stern. I was aware that he didn’t like my mother, regarding her as “snobbish” and that he and my father had not enjoyed a good relationship. My father told stories of his father’s physical brutality and he had memories of many slights against him that rankled forever. His father, for example, had given his treasured pet dog, Bruiser, to the publican of the Rhondda Hotel at Teralba. This was never forgiven. Pop, I knew, had been away in New Guinea during the war. It was said that this had made him even rougher than he already was. He was a keen fist-fighter, and I have been told that he fought in an unofficial ring behind the Cardiff pub and that people took bets on these fights. He was an effective brawler and good boxer and few would beat him. He liked a drink and was a habitual punter on horse and dog races. Never was he remotely unpleasant to me, and there were times when he was offhandedly affectionate. But I could not say that I felt I had a relationship with him. Recently I learned that his father (Ernest Henry senior) had been a pub brawler too, and a coalminer. He had gone to the First World War in one of the tunnelling companies and had come home somewhat damaged. His much younger wife had left him and my grandfather, then aged about 14, had been put into a boys’ home at Mittagong, returning when he was 18 to work at Lysaghts. My great grandfather brought disgrace to the family by molesting a young girl in the 1930s. By then his son – my grandfather – was married. In 1943 Ernie junior, then aged 35, enlisted in the RAAF and served for a time as a guard at Port Moresby, New Guinea, during World War 2. He does not seem to have found it easy to settle down after his (honourable) discharge in 1944, working at different times as an ironworker, truck driver, jockey, coalminer and finally as a water board supervisor. I recall my grandfather often smelled of rubbing liniment, since he operated a sideline as a sports masseur from his back room, fixing the damaged muscles of footballers who were often lined up for his services. Apparently he was very good at this work. My memento of Pop Ray is a carved wooden walking stick he brought back from his service in New Guinea. The New Guinea person who made it was said to have carved it using a sharp piece of broken glass.