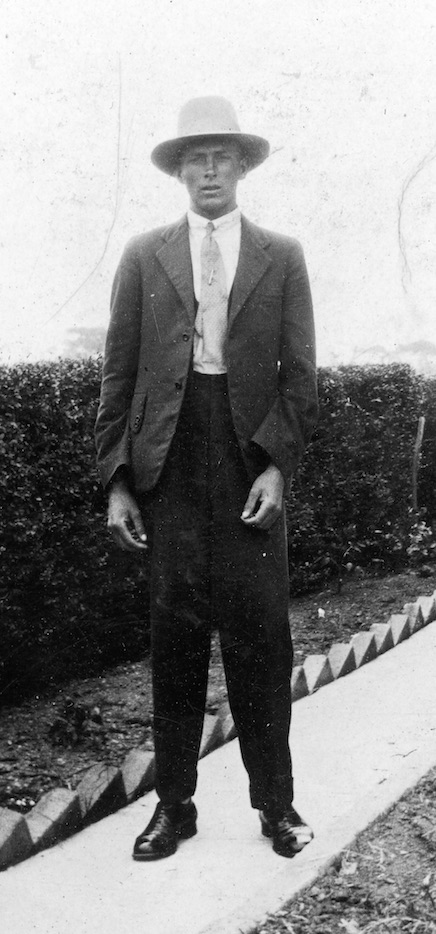

Ernie Eade started work at Rhondda Colliery, Teralba, on January 27, 1927 at the age of 14. He was paid six shillings and sixpence a day, a rate that increased each year by one shilling and ten pence until he reached the adult rate of 17 shillings and sixpence. He worked from 7am to 3pm with a half hour break from 11am.

At that time Rhondda was owned by William Laidley and Co, along with the Co-operative mine at Wallsend. The company’s chief clerk came to Rhondda every second Friday by tram from Wallsend to pay the men their wages. The ostler from Rhondda pit used to pick him up from Boolaroo in a sulky.

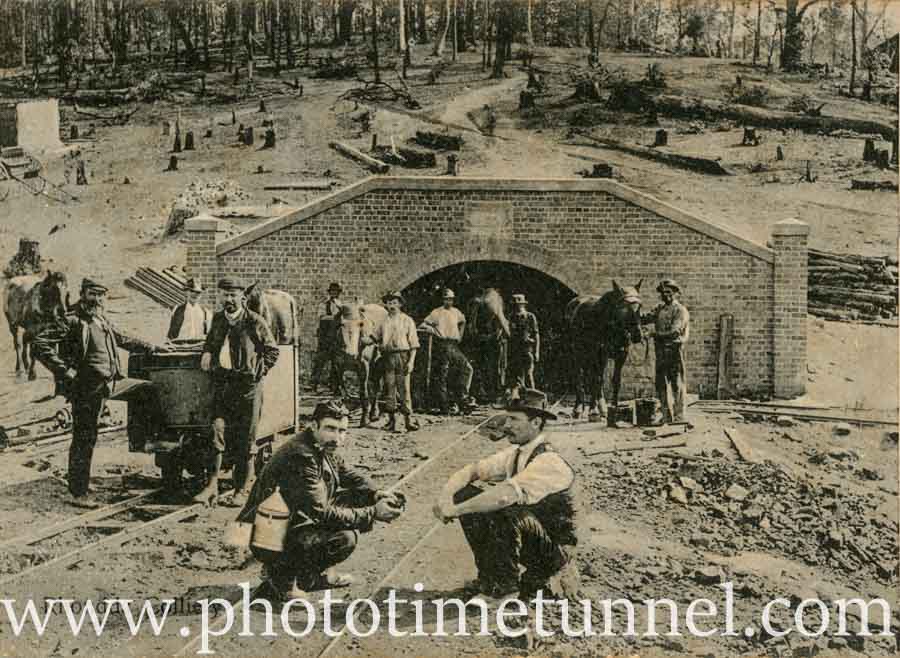

The mine had two steam boilers. One ran surface machinery and the other ran a dynamo that transmitted DC power to “Daylight Tunnel” near Wakefield to operate two coal-cutting machines and various pumps. Ernie recalled that the cutters cut at the floor level, “like a chainsaw that cut out about six inches height to depth of about six feet”. Then miners drilled holes for explosives, firing shots to blow out the coal. The coal was loaded into one-ton skips which were taken to a “flat” by a wheeler who used a horse to draw the skip, then taken by a sidler out to the “rope flat”, where it was connected by a clip to go to the surface. Rhondda used an endless rope, with full skips going out on one road, and empties coming back on the other.

After the 1929 coal industry Lockout . . .

On the surface the coal was tipped onto a belt about 2m wide and 20m long with men on either side with picks to remove stones. “Fine coal” was unsaleable in those days and had to be stored in a “slack box” of about 10,000 tonne capacity. Stockpiled fine coal would routinely catch fire, especially when it got wet.

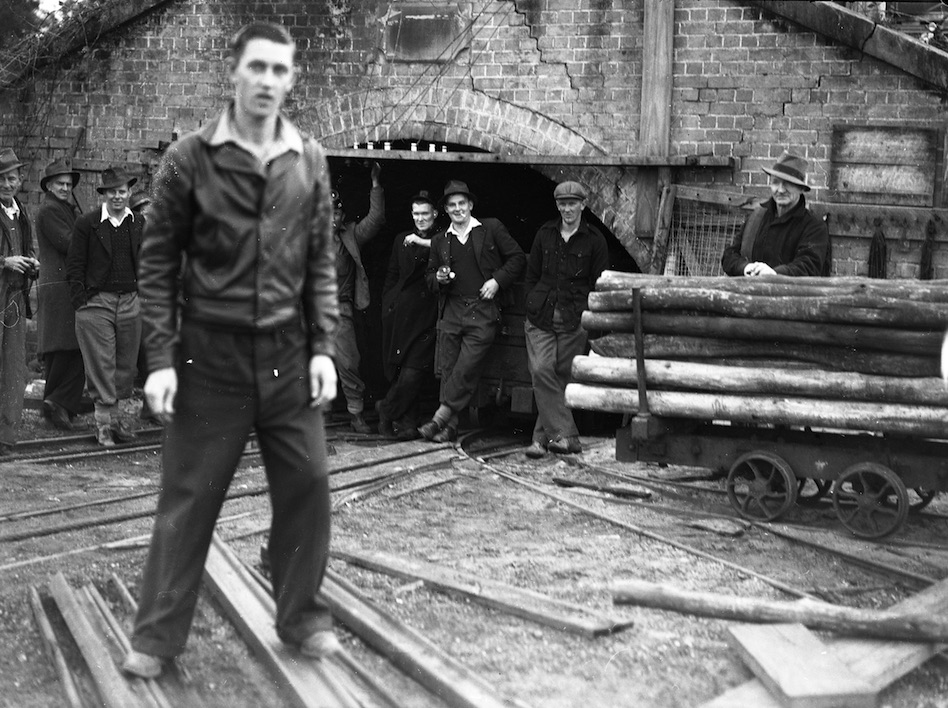

After the 1929 Lockout the coal trade was so depressed that Laidley’s went broke. Four men leased the colliery for a few years and the work slowly increased over about two years when RW Miller took over, changing the skips to one-ton-and-a-quarter. Miller added AC power through to Rhondda, enabling the use of more machines and doing away with horses. Battery powered locos were introduced and the tunnel was widened to accommodate 10-ton skips that gravitated to the pit bottom and were then hauled to the surface with a very large motor. A continuous miner was introduced much later.

“Under the grading system ‘best coal’ was pieces ranging from two-feet to six inches square, handpicked off the belt into trucks. Four inch lumps were called ‘cobbles’, two inch size were ‘nuts’, inch-and-a-half were ‘peas’ and then came ‘fine’ coals,” Ernie said. Changing technology in power generation brought greater demand for fine coal and soon this became most of Rhondda’s trade.

When Ernie started his working life Rhondda was a “naked mine”, without power underground. Lighting was provided by tallow lamps, like small coffee pots, that shed a dim glow.

“At Rhondda the sun in the morning shone directly down the tunnel on the two sets of rails, one side for full skips and the other for empties. I worked about three-quarters of a mile underground, at a turn, and my job was to oil three wheels where the rope went around a corner. If a skip pulled, it could drag the rope off the sheaves and it would be a full day’s job to put it back on. My duties were to meet a set of three skips on one clip as it was coming down and make sure all the wheels were turning and, as it came to the turn, put a shoulder to it and push it around to make sure the rope didn’t come off,” Ernie recalled.

“One day as the full skips started to come out I looked up and saw darkness. I thought the place was falling in but it was only the skips going up and down the tunnel, blocking out the sun and making it dark.”

Ernie went in with the men at 7am but then worked alone and didn’t see anybody until about 11.30am when the under-manager came out for lunch at his nearby house. He would come back less than an hour later and Ernie would see nobody else until about 2.45pm when the men would start to come out of the pit.

After a year Ernie became a “greaseboy”, greasing rollers that held the rope off the ground, then a few months later went “clipping”. “I was putting the coal skips by means of a clip onto a rope in sets of eight then running as fast as I could because I had to put four of these on, leaving sufficient distance apart to be able to take them off at the other end and shove them around the turn and catch the next clip.”

“There was a means of signalling to the engine driver on the pit top by two wires overhead – just ordinary fencing wire – which ran the length of the rope right through to the surface. You used your clip pin, which was an iron bar about 18 inches long with a ring in the top to fit the hand, and when you shorted the two wires together it was supposed to ring a bell on the surface to notify the engine drivers to stop.

“I tried one day to stop but it didn’t work so I rushed down to the head clipper on the next flat and said I couldn’t stop the rope. I ran as fast as I could to the surface. This engine driver was reading his book and not taking much notice of the rope. A good driver could tell if a clip was slipping anywhere because the rope acted similarly to if you had a fish on the end of a line. You could feel the vibration of it. I was exhausted when I got to the pit top and told them there was a clip with four skips behind it and the rope could break. Fortunately the rope did not break.

“I was clipping for a number of years until the rules were changed regarding adults doing what were termed ‘boys’ jobs’. Anybody over 21 years was taken off the clipping job and they put boys on. At that time my mate on the other rope and I were transferred to the surface on the picking belt. But the boys did not have the strength to tighten the clips enough to bring them up the final lift on the rope. The sets would get almost to the top and then they would crash back and bash into the next one causing a derailment and hours of stoppage. After a few days we were put back on our jobs.

“After clipping I went on the coal-cutting machine. I spent about seven years on that and had several accidents. At one time the pipe fell out and struck me on the head and I had seven months off work. Later on we were side-cutting the pillars. That’s when machines first went into pillars. My mate ran a book and he walked around taking bets, leaving me alone to operate the machine. I heard an unusual noise and I glanced towards the pipe to which the chain on the machine was attached. I thought the pipe was pulling out and all I could see was the coal falling in front of me. I turned to run but the wind-blast was so great it picked me up and blew me out of the end. “The men around and about had the working and they knew for days a fall was imminent but we did not expect it to come as far as it did. Fortunately nobody was injured but it was a terrible shock to us all.”

Next Ernie worked in the lamp hut, maintaining the new battery-powered lamps and also the batteries for the electric locomotives. He was still doing this work when Rhondda Colliery caught fire in 1970 and had to cease operations. “It burned for years and the water from the Edgeworth sewerage works was pumped into Rhondda Colliery as a means of trying to extinguish this fire and to get rid of that polluted water,” he said.