BETWEEN the two of them, Ron and Elizabeth Morrison took more photographs of Newcastle and surrounds than they could possibly have counted.

Working at times as photographers on the staff of Hunter newspapers including The Newcastle Herald and the Maitland Mercury, and then running their own press agency in the city, the duo shot portraits by the score, covered news and sports events and worked for commercial clients. Later, they both worked in academia and dabbled in artistic pursuits, as well as publishing a string of successful books.

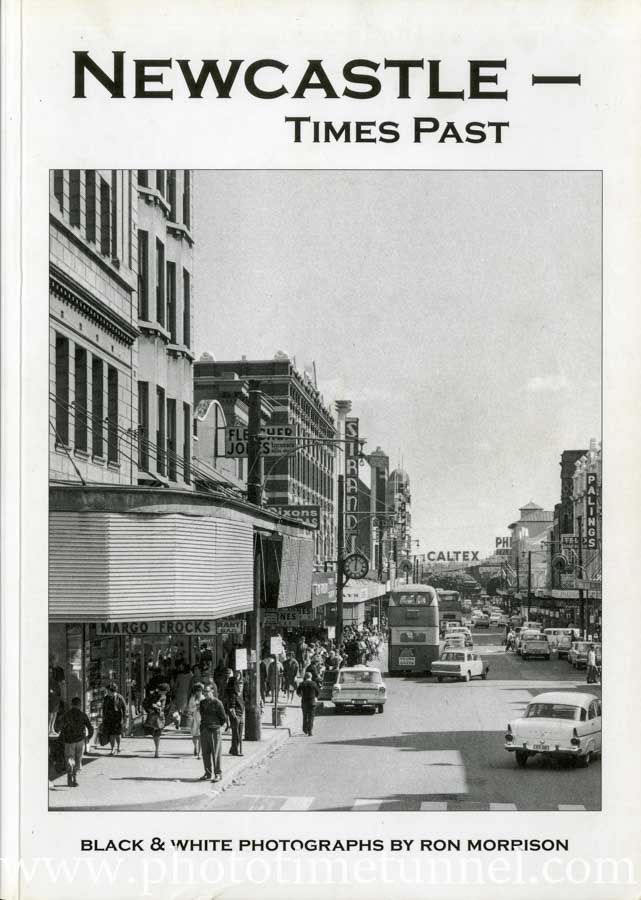

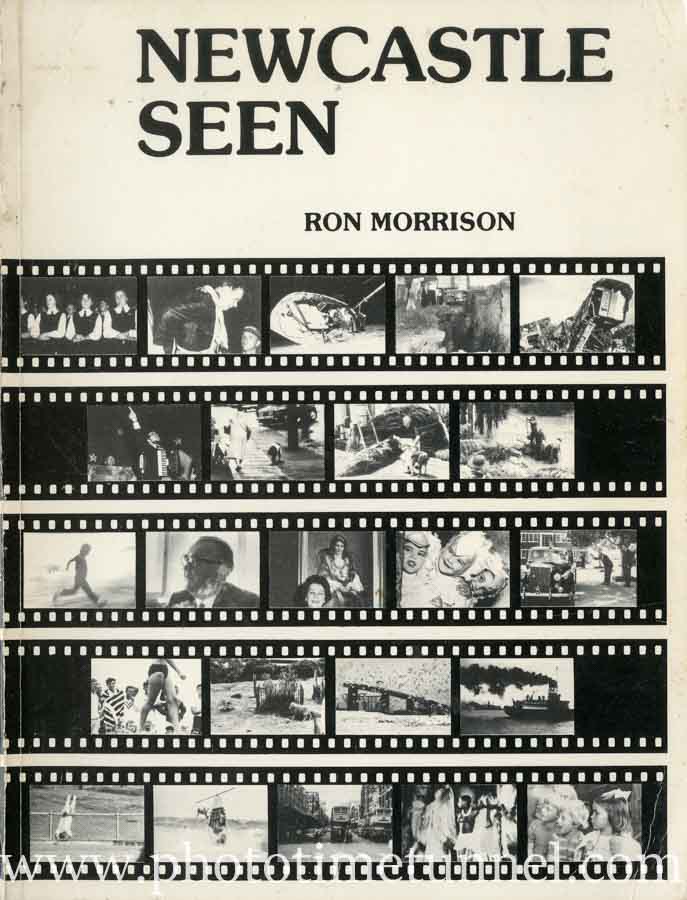

Among their highly regarded volumes of photographs are Newcastle Seen (1989) and Newcastle, Times Past (2005). It was when the second of those books was published that I first met Ron and Liz, establishing a warm friendship.

Since then Ron and Liz have also published Newcastle, Heart of the Hunter (2007) and Those Were the Days, Australia in the Sixties (2013).

When Sylvia and I chanced on a big collection of historical negatives in 2010 we immediately consulted the Morrisons about the technical aspects of publishing a book. The result, Newcastle, the Missing Years, set us on our own course of book publishing, yielding 13 volumes to date.

Our ninth book, fittingly enough, was a survey of the Morrisons’ photographic work during an intensely productive period in the 1960s.

In 2017 the Morrisons, then in their 80s, had decided they would produce no more books. But when they showed us a shipping container on the rural property where they were then living – packed with crates of negatives and prints – it’s easy to understand what happened next. I spent the following months scanning carload after carload of negatives, with the tally finally topping more than 5000.

Ron had predicted that many of the images would be found to be too mundane for publication, and also worried that some of the film was deteriorating rapidly and might be too far gone to scan. These fears proved mostly unfounded. True, much film was irreparably lost. But most was either in good condition or recoverable. And a large amount of the material that Ron had feared would be “too dull” for publication was anything but. Most of the jobs shot by Ron and Liz resulted in series’ of negatives, only one or two of which were ever printed. When all the negatives were scanned, many interesting images re-emerged from obscurity to surprise and delight.

Photos that had been tightly cropped to suit the needs of clients were seen again in their entirety, and in many cases the wider contexts made them more fascinating, especially after the passage of time. Streetscapes that seemed “mundane” to Ron Morrison when he photographed them in the 1960s were strange-seeming when viewed against today’s rapidly changing Newcastle.

Ron proudly boasted of teaching Liz how to take photos, and some of Liz’s work shines in the book. One example is the striking series of shots – taken over several days – to illustrate the horrific “double headless murders” that rocked Maitland in 1960. Ron was out of town when the story broke, and it was up to Liz to shoot the pictures so keenly sought by press clients. The result, published in the book, is a remarkable noir essay.

The Morrisons gave me a free hand to select the images for the book, restricting their input to suggestions and the provision of extra information about the pictures. The result is a broad survey of Novocastrian life during the period from 1959 to the early 1970s, featuring a smorgasbord of news photos, interspersed with commercial jobs, portraits and artistic images.

It is worth remembering that, as the 1960s dawned, World War II had only ended 15 years before, and the marks of the war and the Depression that preceded it were still present. In 1960 Newcastle was an industrial city with plenty of relatively well-paid work, even for the unskilled. Technology, much of it triggered by a rapid global surge in production, research and development prompted by the war, was giving birth to the consumer society now so familiar to Australians. The statewide electricity grid made it possible for new markets in electrical consumer goods to expand. New fashions in music and entertainment likewise fed into the growth of consumerism. People began to demand better homes, better cars, better clothes and better education for their children.

Television became ubiquitous and began to carve into the markets previously occupied by radio and newspapers. The controversial Vietnam War took place against this backdrop of “new media”, which almost certainly made it even more unpopular than conscription and political dissent had already done.

And yet society was still conservative by the standards of the 21st Century. Censorship was the norm, in films, books and other publications. Most institutions were heavily dominated by males. White Australia was still taken for granted as a social standard. Aboriginal Australians were only granted the right to vote in 1962, and were only included in the Census in 1967.

On the whole this book is a compilation of minutiae: small and ephemeral details of the kind for which news publications had an insatiable appetite. Put together they form a kaleidoscopic survey of a city and a time now gone, with faces, places, events and activities that are certain to jog the memories of many readers.

Ron and Liz donated a large collection of negatives to Newcastle Region Library, and in 2017 transferred another large batch of material to Greg and Sylvia Ray, following collaboration on the book, Newcastle in the 1960s.

Ron Morrison passed away on July 29, 2022. His last year of life was punctuated by his second major flood experience. The house he was occupying with his son and family at Woodburn, near Lismore, was inundated and many of his personal records and photos were destroyed.

Hi Greg – it’s not really accurate to say “Aboriginal Australians were only granted the right to vote in 1962”. From 1829, everyone born in NSW / Australia was a British citizen by birth, including Indigenous Australians. When the colonies became self-governing in the 1850s all adult (21 years+) male British subjects, including Aboriginal Australians, were entitled to vote in South Australia from 1856, in Victoria from 1857, New South Wales from 1858 (and Tasmania from 1896). When Queensland gained self-government in 1859 and Western Australia in 1890, those colonies denied Indigenous people the vote. In 1902 the Commonwealth Parliament passed its first law on federal voting (the Commonwealth Franchise Act), granting men and women in all states the right to vote in federal elections but denied federal voting rights to ‘aboriginal natives’ of Australia, Asia, Africa, or the Islands of the Pacific (except New Zealand) who, at the time of the Act, did not already have the right to vote in state elections i.e. in QLD and WA. To recognise the war service of indigenous Australians, in 1949 the right to vote in federal elections was extended to indigenous people who had served in the armed forces, or were enrolled to vote in state elections. The 1962 Act really added the final piece of the jigsaw, ensuring that the right to enrol and vote in Federal elections was extended to all Indigenous Australians, regardless of State law or military service.

Hi Mark,

Many thanks for that excellent clarification.

Greg