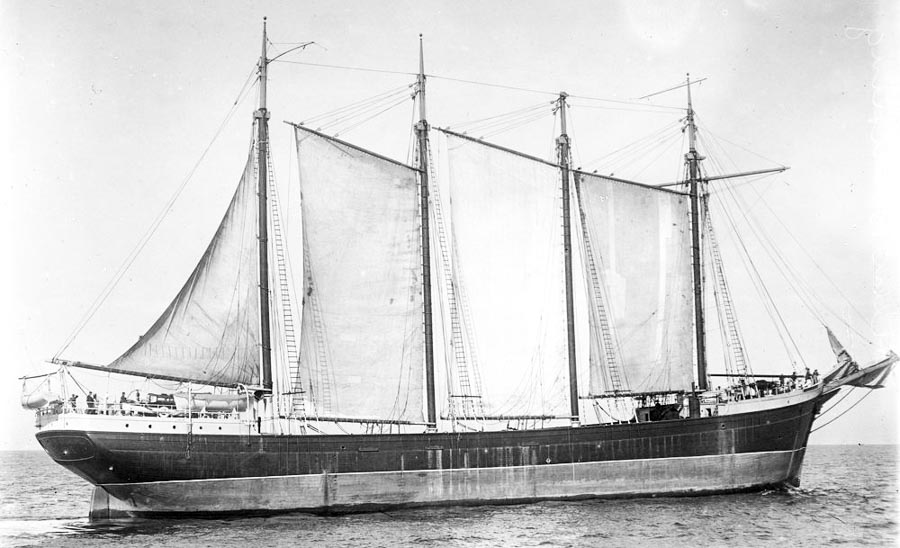

Stockton schoolboy Leslie Harris was 10 years old on January 5, 1922, when he went aboard the four-masted schooner Helen B Sterling, along with his mother Edith and his father George – the captain of the ship. The first mate, whose surname was also Harris and who may have been a relative, also had his wife aboard. The ship was carrying coal from Newcastle, NSW, to the Society Islands (part of French Polynesia) and San Francisco in the USA.

Aside from the members of the Harris family there were 15 crew members aboard. The schooner was owned by American ship-owner Edward Robert Sterling, whose Sterling Line of sailing vessels carried timber from the United States to Australia and New Zealand. The Sterling Line was initially successful, but suffered a string of misfortunes which led to its ruin. The first disaster began to unfold when the Helen B Sterling left Newcastle with young Leslie aboard.

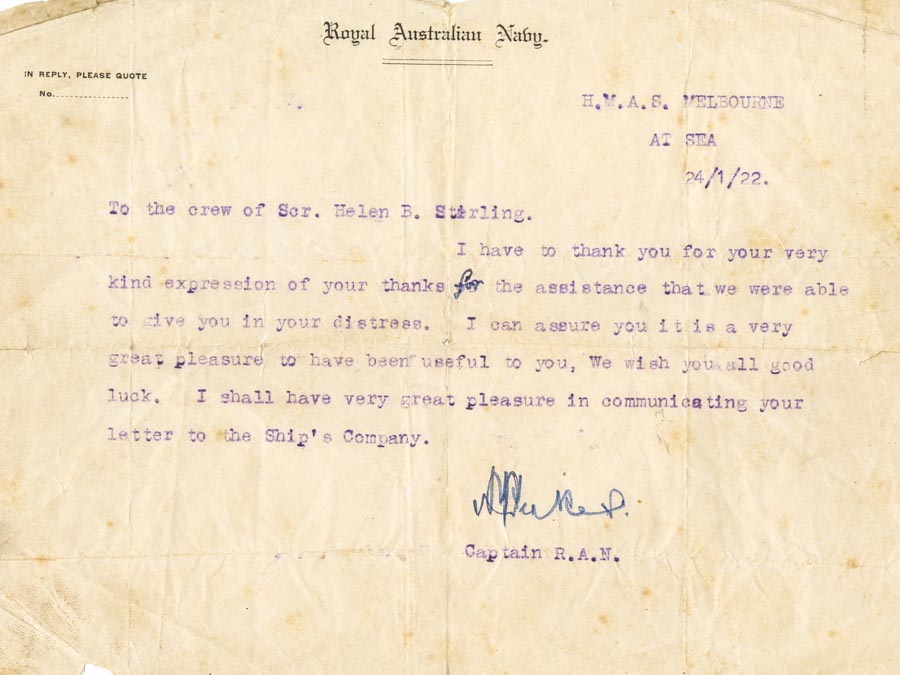

The schooner was destined to be lost, and it was by the most extreme good luck that the crew and the Harris family were rescued at sea by the Royal Australian Navy’s HMAS Melbourne. Apparently the schooner and its cargo were uninsured, so its loss was a heavy financial blow to its owner.

Shortly after this near-tragedy, young Leslie Harris wrote an account of the episode as a composition for his teacher at Stockton Primary School, Miss Monaghan. Some years ago I was privileged to photograph this remarkable document, which I transcribe here:

5th Feb., 1922

Dear Miss Monaghan,

This is the story of my voyage and wreck. Safe home once again and it all seems mysterious.

I set out on the 5th January on the Helen B Sterling with my parents from Newcastle, having 2700 tons of coal for the Society Islands and San Francisco. The second day out at sea there was a fire on board and slight damage was done to our ship, burning a hole in a beam.

The trip was pleasant until the 9th January when there was a gale about 10 O’clock at night. It moderated but at 12pm it blew furiously and at 2pm again subsided. One sail was blown away much to our amazement.

The 18th brought about another strong cyclone which lasted many days. On the 20th the mainmast was broken to the eyes of the rigging and then to the eyes of the deck and finally we were left with only three masts.

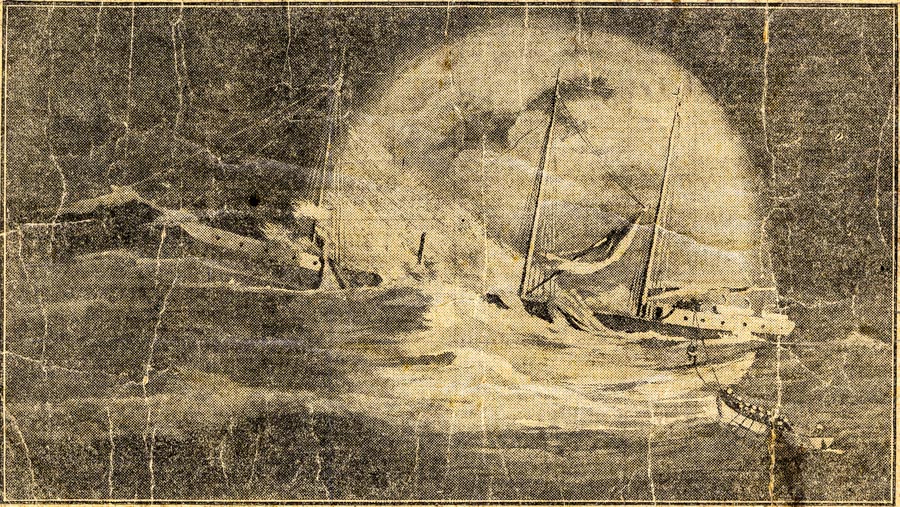

The experience was wonderful. The waves were mountains high and splashed overboard on each side until they met in the middle. The Sterling was filling with water and must sink as only eight inches of her sides were above water.

Fortunately the wireless was not interfered with. Dad sent the SOS call and in half an hour the HMAS Melbourne picked our message up. At this time the Melbourne [was] travelling at 14 knots per hour and in thirty five minutes she worked speed up to twenty five knots and the four boilers which were out of commission were set in action causing this great speed to our assistance.

The return wireless from the Melbourne said: “Keep up heart. We will find you.” This was sent at 12pm and at 2am the Melbourne wireless said “I will come to the windward of you and pump oil on the waves. I’ll keep my searchlights on you and I will come down to the leeward and lower my starboard boat and then go to the windward again and stop there”.

We were all overjoyed and wonderfully excited at the Melbourne’s approach. She came almost to us before we could notice the mast light, then Dad gave them the bearings by wireless from the compass which were NNW. Soon she was to our assistance. The Commander of the lifeboat called out through the megaphone to Dad: “Captain Harris, lower your spanker and see if there’s any wreckage to the leeward”. All was clear so he came to the stern again and then ropes were thrown by the second mate to connect the Sterling with the boat. Next the lifebuoy was thrown which was strapped over our shoulders on leaving our ship. Then we were hauled one hundred yards through the water. After two hours we were all safe aboard the Melbourne. My poor little cats were thrown about eighty yards tied up in a pillowcase as the second mate tried to save them for me. The smaller one had to be drowned and we were so sorry to lose our little pal. My black cat is aboard the Melbourne now at Dunedin. Then we went to Auckland and stayed there for ten days and returned home on the Mahena, having a fine placid passage home.

I remain your loving pupil,

Leslie Harris

It’s clear that young Leslie was a very lucky boy. Lucky that the Helen B Sterling had a wireless set and was able to transmit an SOS. And lucky that HMAS Melbourne was within striking range and capable of an enormous burst of speed to effect the rescue. Lucky too, that Melbourne’s officers – Captain Henry Feakes (later Rear-Admiral) and Commander Wilfrid Ward Hunt – were the types of men who would strive to save the lives of the crew aboard a stricken sailing ship, even if the chances of success seemed slim.

When the Melbourne picked up the SOS it was on its way to New Zealand for naval exercises. Captain Feakes realised he was 340km away, and would have to head through stormy seas to make the attempt. But no ships were closer, and with its superior speed the Melbourne could arrive in the area 12 hours sooner than any other vessel. He knew also that pinpointing the location of the sinking ship would be extremely difficult.

In the Helen B Sterling’s radio room was wireless operator Raymond Shaw, who later wrote a vivid account of the episode in the Australian newspaper Smith’s Weekly. He described how, on January 21, he had been working hard with the rest of the ship’s crew, operating the pumps by hand because the pumping engine had broken down at the storm’s first onset. Before he went to bed, in his wet clothes, he tried to make sure his radio set was workable, thinking it might be needed later, since a worse gale was expected in a few hours. As Shaw tried to sleep he became aware of an unfamiliar noise breaking through the roaring of the storm. Something had “fetched adrift and was pounding to and fro across the waist,” he wrote. That something was the mainmast. As soon as he saw the broken stump of the mast at dawn next morning he looked automatically at the wireless aerial. By lucky chance, the mast had already been shortened by a previous accident. If that had not been the case, it would surely have torn away the aerial.

Given orders to send an SOS, Shaw went below to his radio room. But before the radio set could work, he had to start the engine that powered it. With help he managed, then set to work on the wireless key. For hours he repeatedly sent the SOS signal. From time to time the current failed and he had to claw his way to the engine room to put the belt back on the generator pulley, and eventually this task became so frequent that an injured sailor was given the job of holding the belt on its pulley with a piece of wood. Next, the wireless set’s high-tension cells failed and he had to substitute lighting cells to keep the seemingly fruitless signals going while the storm kept raging and the ship steadily filled with water.

Finally, at 8.30am Shaw received a message from Awanui, New Zealand, advising that the Australian navy cruiser HMAS Melbourne was on its way. Soon he made direct contact with Melbourne, but by now the sinking ship’s engine room was flooded and the generator engine belts stretched and failed. A coat of varnish on the belts got things running again. By the afternoon the voice of the Melbourne’s wireless operator was fading as the receiving cells slowly died. By now, crew members were asking Shaw to send farewell messages for their families and by 2pm he was ordered to the deck to take his place in a lifeboat. The sea was too rough to launch the boats, however, and the first attempt cost a boat, smashed by the sea. The plan to abandon ship was dropped, and Shaw went back below to find a solution for his failing wireless set. By 6pm, with lighting cells from the engine room and the set dried off, it was again possible to receive.

About 7.30pm he told the Melbourne that his generator was almost out of oil and must soon fail permanently. He told the Melbourne that he would try to call again at midnight if the ship was still afloat. He called again at 11.45 and the Melbourne replied that it was close and would arrive about 2am.

“I kept the connection going till 1.45 and then something white poked up out of the sea,” he wrote. It was Melbourne’s searchlight, and Shaw quickly radioed that he could see the light and provided bearings. All the sinking ship’s hands were clustered on the poop, waiting.

Writing about the incident years later in the book White Ensign – Southern Cross, Feakes described arriving – after 13 hours hard steaming – in the area where he believed the schooner should be. By now he was low on coal and the prospects of success were poor.

“I gave the order for a final call with our most powerful signalling projector all round the horizon. To our relief and joy a message came through: ‘I can see your light’,” he wrote. Melbourne had arrived just in time. The schooner probably had less than an hour left to float and the people aboard were huddled on deck, soaked to the skin and frightened.

The rescue that followed was a masterpiece of seamanship on the part of all concerned, particularly the volunteer crew of the Melbourne’s cutter, which was under the personal control of Commander Hunt.

Interviewed immediately after arriving in Auckland with the rescued people from the schooner, Commander Hunt described the scene: “A high sea was running and waves were breaking right across the practically waterlogged ship, although her poop and forecastle were well above water. The crew and the ladies were perched on the poop. The wind had eased somewhat and it appeared that with careful handling the crew could be taken off by one of Melbourne’s boats”.

Getting the boat away from the Melbourne was problematic in the high sea, and it was far too dangerous to take the boat alongside the stricken schooner. Fortunately, the Melbourne’s powerful searchlight was able to illuminate the scene. A line was passed between the ship and boat, and the stranded people were brought across one by one using a device known as a “breeches buoy” – essentially a pair of canvas pants attached to a lifebuoy and a lifeline.

.

It took two hours of hard work to get everybody off, and by then the 12-oared cutter was heavily overloaded and getting it aboard the Melbourne was another challenge. All in all, it was a remarkable rescue, and the ship’s company were received as heroes in Auckland Harbour.

As for young Leslie Harris, as he was hauled aboard the Melbourne the Stockton schoolboy fell into the arms of 23-year-old Novocastrian torpedo-man Harry Dagwell.

He told a reporter in Auckland that although he had been frightened during the ordeal, “what had grieved him most was the thought that he might never see his two little sisters again”.

Leslie grew up and became a foreman boilermaker at Newcastle State Dockyard. He died in 1984. Three years later one of his grandsons, Michael, joined the Royal Australian Navy and spent his first months at sea aboard the modern incarnation of HMAS Melbourne.

An excellent article about the ill-fated Sterling shipping line can be found by clicking here.

Wonderful photos of the Sterlings, by photographer Sam Hood, can be seen here.