In the 1920s and 1930s the Commonwealth Bank’s “Industrial Purpose Accounts Officer” in Newcastle was a Mr John Henry. Mr Henry made it his business to visit some of Newcastle’s bigger industrial plants and he wrote some accounts of his visits in the bank’s staff journal, Bank Notes.

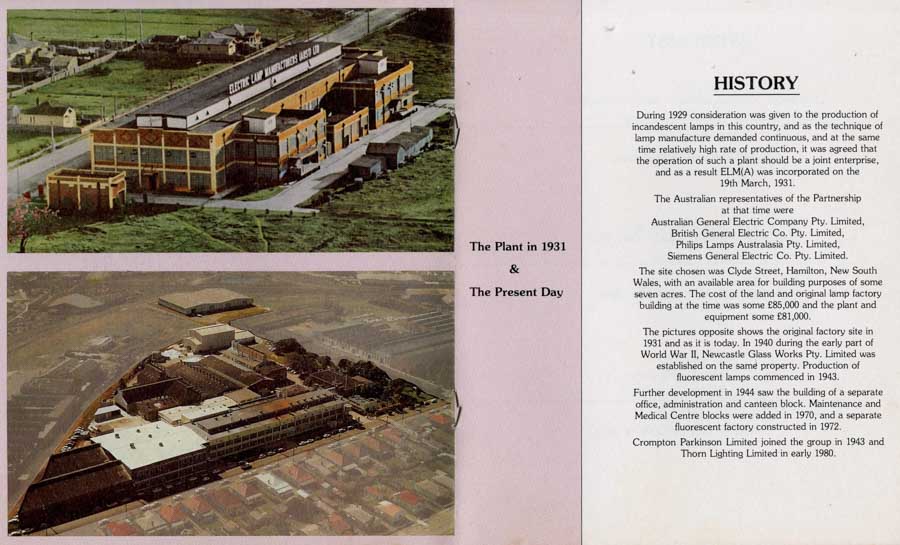

Mr Henry visited Electric Lamp Manufactures Australia (ELMA) in 1933, when the factory – in Clyde Street, Hamilton – was just two years old and regarded as the peak of modernity. Notably, the major light bulb manufacturers decided to set up the factory as a joint venture, simply branding the identical globes with their own logos as they were produced. Most light bulbs that were made in Australia were made at this Newcastle factory.

This co-operative approach wasn’t quite as it was portrayed, however. Much of the co-operation was designed to ensure that all light bulbs were likely to fail after the same amount of use. While it was possible, even then, to make light bulbs that could last for decades without failing, this was obviously damaging to profitability. It seems the plan was to make light bulbs that would fail, as the documentary, The Light Bulb Conspiracy appears to show.

You can watch the The Light Bulb Conspiracy documentary by clicking here.

Mr Henry’s 1933 article follows:

Having had the opportunity of seeing over one of the most interesting industries of the present time I hope to convey to fellow officers what was, to me, an educational treat – the inside story of Electric Lamp Manufactures (Aust) Ltd, of Newcastle.

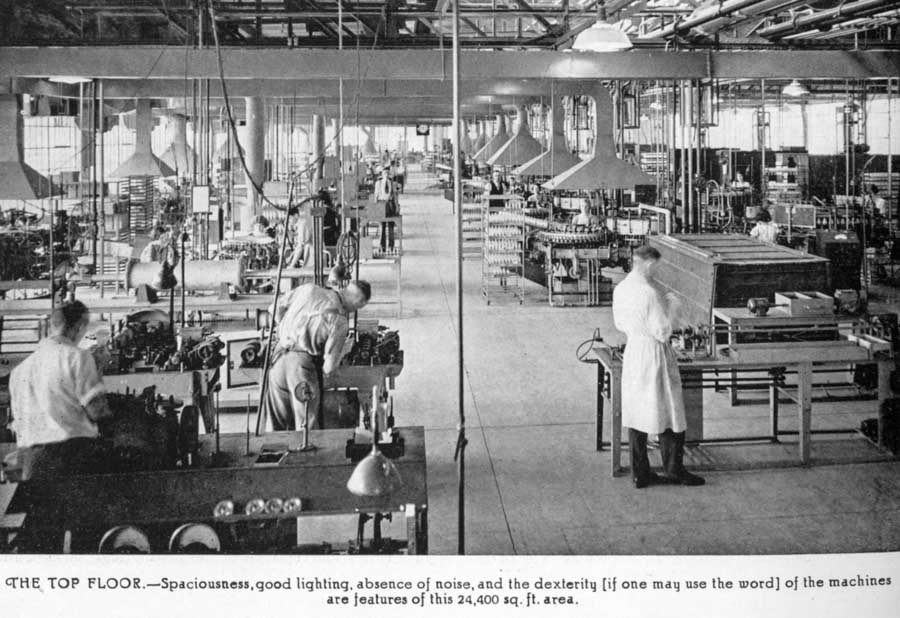

The building itself, which is two-storeyed and cost £180,000 to erect and equip, is fitted with the most intricate machinery and fascinating test apparatus known to modern industry. The top floor of the building covers 24,400 feet of space and some idea of the length of the building may be gauged from the fact that while a very large clock hangs in the centre of the room it is almost impossible to tell the time from either end of the floor. What impressed me most was the almost entire absence of noise whilst the various machines are working. The cleanliness and absence of excessive heat were also features which impressed me very much. I was informed whilst on my tour of inspection that the Australian men, women and girls who make, test and pack these millions of lamps are considered the most highly skilled operatives procurable, and it should be remembered this one factory has the advantage of all the research work and achievements of the great scientific laboratories of the world and is capable of supplying all the electric lamps Australia can possibly need for many years to come.

The employees, about 200 in number, whose activities are performed under ideal conditions, appear actively aware that they are engaged in a great and unusual industry. I noted that every comfort appears to have been provided for them. Beautiful luncheon room restrooms and locker rooms for all, and even a tennis court for day and night play has been put down for the recreation of the employees. The manager’s office is one of dignity and comfort. Mr Buisma, the manager, received me most courteously and ensured a pleasant and instructive tour of inspection by putting me in the hands of the assistant manager, Mr W.G. Culpitt, who described every possible part of the machinery and answered tirelessly my numerous questions. The offices set apart for the staff are modernly ventilated and beautifully fitted and the noise of numerous typewriters certainly established the feeling we were about to be shown through a very busy industry.

A great and unusual industry

The ventilating system of this factory is most important. Practically every machine contains a series of fumes and the system keeps the whole factory at an equable temperature. An overhead electric motor drives a large fan and sucks the heated air from the cowls over the machines and expels it through a large window, thus maintaining a continuous current of air throughout the factory. It is a credit to Australians that in the space of less than three years operatives can be found who are now able to compete with any in the world in this industry. I was taken through the large engine room on the ground floor. This wonderful and strikingly clean engine room supplies several types of gases and various forms of electricity required by the large factory and here again I was strikingly impressed with the absence of noise or noxious odours. The gas meter is the largest I’ve ever seen.

At almost every stage of production it is necessary, obviously, for glass to be heated to a semi-molten state and during this heating and the subsequent cooling-off process certain strains may develop in the fabric of the glass. These strains are eliminated buy annealing (heating the glass a second time), and never in the whole construction of the lamp is this precaution omitted. A “miracle in steel” is the bewildering flange-making machine, in which glass rods pass, and from which perfect lamp flanges emerge. Let one flange deviate in the slightest degree from the rigid standard of exact size and across comes the automatic arm to throw the delinquent into the reject been. This is truly a highly ingenious piece of mechanism which automatically converts glass tubing into work may be described as the beginning of the lamp the flange as the machine rotates the end of a piece of tubing is heated by a series of gas jets and when sufficiently high temperature is reached a spindle rises and makes the flange. This is allowed to cool and then is cut to the correct length by rotating knife then suspended for an instant over aflame to remove any strain which might have been introduced into the glue us by the preliminary beating and finally the flanges ejected into awaiting tray. The completed flanges maybe seen passing out of the machine at the rate of 1300 per hour. This is truly a marvelous piece of machinery and left me wondering whether anything in modern manufacturing practice could be more expert.

A complex marvel of ingenuity

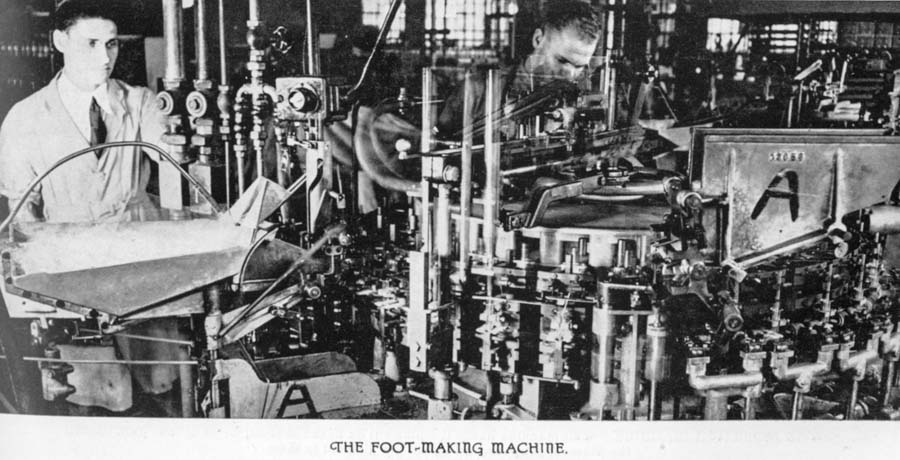

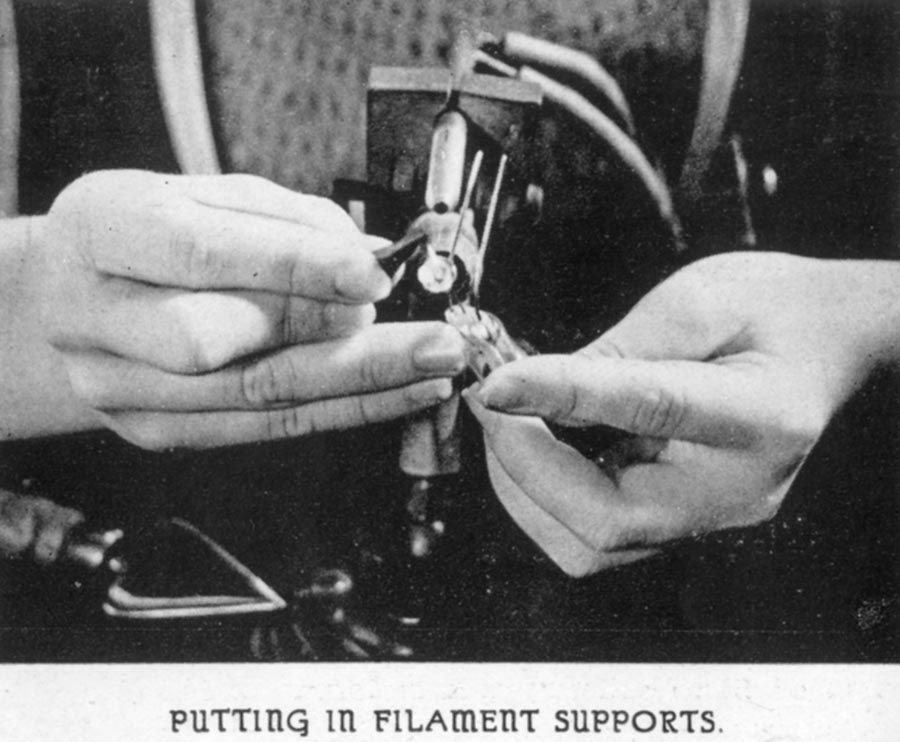

I was next shown a complex marvel of ingenuity – the foot making machine. This machine feeds itself with flanges, rods, stem tubes and leading-in wires, and after automatically performing 13 operations delivers the finished foot to a conveyor which passes slowly through an annealing oven, removing any strain which may have been introduced into the glass. If you have ever examined an electric lamp closely you will have noticed that the actual filament has wire supports. This wire, which is made of molybdenum and which is passed through a special machine to ensure perfect cleanliness, has to be inserted into a molten glass rod with perfect precision. The machine which does this is known as the mounting machine and it provided for me a further incidence of astounding skill. It flattens the nickel ends of the two leading-in wires and forms them into a hook on which the vacuum fingers – almost too uncanny to watch – place the filament. The machine then closes the hooks, cuts the molybdenum supports to the correct length, bends back the leading-in wires, blows the filament against the supports with air, twists the ends of the supports into eyelets and produces the finished and perfect mounting and filament of the electric lamp. Here again strict precaution is necessary. There must be a complete absence of oxygen in the lamp. Hence that absolutely modern innovation – the spraying of the filament with a special compound known as “get”. A spraying mill sprays the finished feet of the lamp after they are received from the mounting machine, thus ensuring a complete absence of air when the lamp is evacuated.

Another very interesting machine that I had explained to me during my inspection was the sealing and exhausting machine. To watch this machine moulding the mounting and the plain bulb into composite whole and burning the brand into the bulb at the same time, also to see the vacuum hand picking up the growing lamp to send it on a journey through a circular oven is undoubtedly fascinating. The machine further fuses feet and blank bulbs into one, at the same time burning-in the brand indelibly. It then exhausts the bulb and fills it with nitrogen five times to ensure perfect cleanliness and finally, in the case of gas-filled lamps, fills it with argon. At the next stage we saw a remarkable demonstration of high speed and dexterity. Two young ladies worked side-by-side at the capping mill, placing caps previously filled with a special cement over the top of the bulb. They did this with almost unbelievable accuracy and the two leading-in wires never failed to pass through the cap with faultless precision. The operative alongside the rack of lamps from the capping mill examines them for appearance and cap-placing and this person is amongst the most highly trained in the entire organisation. No lamp passes her if it is not perfect in appearance and accurate as to the cap and the soldering of leading-in wires. The lamps are then branded on the bottom later they are burnt in indelibly by the sealing-in machine. After all the different machines had demonstrated their high efficiency, and the lamps that we had watched through various stages were finished, we came to perhaps the most important stage – the testing. The tests are very exacting and thorough.

Emit an almost blinding brilliance

The most spectacular of the tests and rials to which the lamps are subjected begins at the “burning frame”: the Tesla Oosterhys high-frequency test being here applied. A skilled operative passes a high-frequency rod over the bulbs. From the top of this rod, right through the glass to the filament itself, a continuous spark or arc passes. The varying colours of this spark reveal the purity of the gas in the lamp or the slightest presence of oxygen in the bulb. Any fault means immediate rejection of the lamp in question. Then the lamps are lighted for the first time – one sees the current being gradually turned on – the lamps glow, then as the full voltage comes into play, they emit an almost blinding brilliance. These batches of lamps are burned for a definite period at a voltage both higher and lower than that prescribed for their final use.

There is also a “life” testing room, where lamps (taken at random from each day’s production) are burned for 250, 500, 750 and 1,000 hours, and some burned to destruction.

The most modern development in the manufacture of lamps is the frosting of the bulbs on the inside. Before this process is carried out every bulb is most carefully washed and cleansed. The inside-frosting machine then sprays the inside of the clean bulbs with a frosting dressing; this mechanically treats the glass by etching, and washes them out with water. As the frosting process leaves the bulb slightly less mechanically strong than previously, they are again automatically washed out with a strong acid, which restores their strength. After this process the bulbs are dried and placed over a strong light where a skilled operative searches for faults which may have developed. All blanks – inside-frosted and clear – are placed over a strong light and examined for flaws before being despatched to the sealing-in machine. Lamps of larger sizes are mostly finished by hand. At the sealing-in machine the lamps automatically have their foot and blank bulb fused into one, the leading-in wires being soldered to the cap by hand, but in the case of smaller lamps this operation is done automatically by the capping mill.

The filament is spot-welded by hand to the leading in wires. This is one of the processes in the making of the foot of the large lamps, the filament supports being placed by hand into the glass stud of the foot of the lamp, and the writer was astounded at the accuracy with which these supports were placed there by the operative. The hand-threading of the filament was another act of speed and accuracy which impressed me very much.

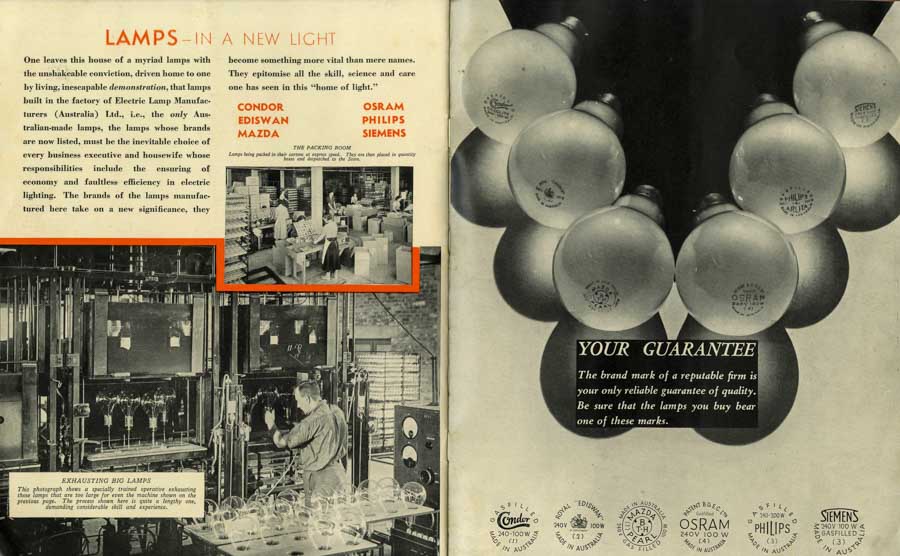

The bulk store room was itself worth a visit. There was a stock of over two millions of the various brands of lamps, viz Condor, Ediswan, Mazda, Osram, Philips and Siemens.

Sent to overseas testing laboratories

In addition to the numerous tests conducted, the manager informed me that the lamps are frequently and regularly sent to overseas testing laboratories for the purpose of maintaining careful check, and to ensure that the Australian standard of manufacture is fully equal to the highest in the world.

It is the expressed wish of the management of this great lamp manufacturing firm that should any of our readers from any part of Australia or the Continent visit Newcastle, they should take advantage of the opportunity to make a similar tour of inspection.

********************************************************************************************************************

ELMA produced its last light globe in 2002. More interesting information about ELMA can be found here, at the Legacy Lighting website.

Another of John Henry’s articles, about a visit to Vickers Comsteel in 1929, can be found here.