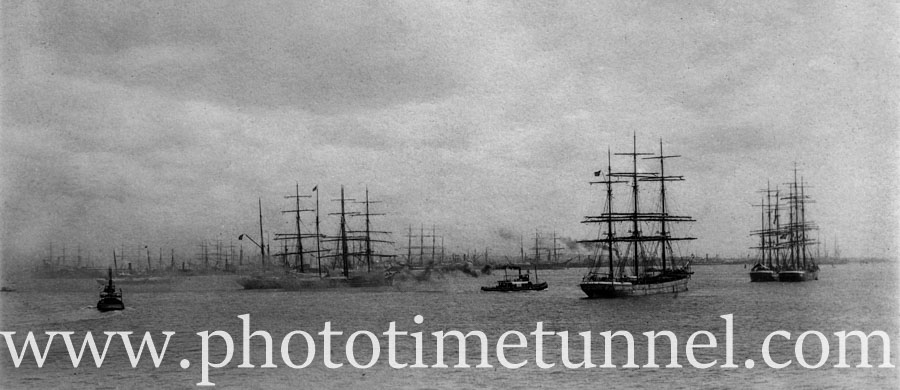

WHEN steamships were perfected, they inevitably put an end to the long era of sail as a means of trading commodities across the globe. But sailing ships lingered for decades, and circumstances made Newcastle, NSW, one of the last of the great sailing ship ports. In the early years of the 20th century, the city often hosted as many as 80 sailing ships at once, almost all of them taking Australian coal to the west coast ports of the Americas.

Prevailing winds across the Pacific Ocean meant the sailing ships could catch the trades to Australia in the tropical latitudes, then fly back east on the wings of the strong winds in the lower latitudes. This free energy, coupled with the fact that the west coast American ports were hungry for coal to run their railroads and mines, gave sailing ships one last profitable niche. Unfortunately, waiting times for cargoes at Newcastle were very long, and that fact helped put more of a squeeze on the trade.

During those golden sunset years of sail, Newcastle’s Nobbys headland was a landmark known to many thousands of deepwater sailors to whom rounding that clumpy little headland was synonymous with reaching safety.

Many sailors wrote about their travels, and numerous books contain interesting references to Newcastle during the years of the “west-coast coal trade”.

The well-known book Mate in Sail, by James Gaby, has some interesting passages relating to Newcastle. Gaby visited Newcastle in the Poltalloch and describes going:

. . . straight to our dolphin berth at Stockton and were tucked in between the Andre Theodore, a French full rigger, and the Jordon Hill, a big Britisher astern. The Jordon Hill was the southernmost vessel at Stockton and from her away to the north was literally a forest of masts. Most ships double-banked and in some places moored three abreast giving depth to the forest-like appearance of the multitudinous masts and spars. There were ships of all nations and rigs, from a barrel-hulled American four or five mast schooner to a graceful skys’l yarder, some discharging ballast, others awaiting charters or their turn for a loading crane at the Dyke Wharf. At six o’clock every morning, except Sundays – although Poltalloch turned to at seven – the forest came to life with the noise of chipping hammers pounding out a steady beat on the empty steel and iron hulls. The sound never stopped except during meal breaks but rose and fell all day until about five thirty in the evening when the chippers put away their hammers.

Newcastle days and Newcastle nights! Nostalgic times for the deepwaterman who remembers the sight of a big barque or full-rigger being nosed up to a farewell buoy’ so low in the water that her sheer is beautifully displayed and the fine days after rain when the mast-forest broke out into flower as white sails were loosed and hung drying in the sunshine. He speaks in silence the good wishes for the ship following her tug out past Nobbys when he watched until she spread her wings and sailed away into the voyage ahead. He remembers the thrill of watching a big full-rigger set sail of the lower farewell buoy and glide gracefully out to sea without the assistance of a tug as the British ship Cumberland did one fine Sunday morning. Then there was the competition to be first to identify a stranger newly arrived.

And there were the nights! The arrival of Mr Hare in the mission launch to ferry us down to the Missions to Seamen Hall and to pick up the Invergarrys, the Vimeriras and others on the way. There were nights when a ship with an extra good chantyman was so proud to have him up on the stage leading the chanties for fifty or more square-riggers to “Roll the cotton down!” Not in drawing-room fashion, but in good old main deck style. Saturday nights we received ten shillings and went across to Newcastle by the ferry Heather Bell to spend it. There were three places to find us: at the Victoria Theatre with Dix and Baker’s vaudeville show, or on the rounds of the seamen’s outfitters shops or, for those otherwise inclined, down in the Black Diamond or other waterfront hotels where a sailor got enough beer and fight to last him until the following Saturday night when, if the “Old Man” felt in a good mood, he might get another small advance.

In the tin shanties along the empty ground opposite the ships at Stockton, the walls were covered with pictures of ships framed in miniature lifebuoys, ships on post cards and even in handsome paintings. Real little marine art galleries. They were staffed by good looking lasses who sold candies and soft drinks. There was always a good welcome and a chair for the sailor who dropped in.

Another good description is contained in the book Gipsy of the Horn, by Rex Clements, who arrived in Newcastle in 1903 in the ship Arethusa:

The harbour was a wonderful sight by reason of the great number of deep-sea sailing-ships then in port. There were no less than a hundred and sixteen of them when we arrived, not counting steamers or coasters, and a grand show they made. Right away from Queen’s Wharf, just inside the Bluff, up past the Dyke they lay in an unbroken line as far as Waratah, or “Siberia,” as it was called, from its remoteness to everywhere else. In the Dyke, where we were lying, the ships lay three deep and there was a double row of them over on the other side at Stockton. Masts and yards were packed as thick as bristles on a hedgehog. During the day there was as much activity afloat as ashore, in consequence of the tremendous number of steam-launches, ferry-steamers, chandlers’ boats and ships’ gigs dodging about among the shipping.

We only stayed at the Dyke a few days, then shifted down to Queen’s Wharf to discharge our cargo. Queen’s Wharf was the best berth in port and only a couple of minutes’ walk from Hunter Street, Newcastle’s principal thoroughfare.

We found Newcastle a very lively and pleasant little town, with so many ships in harbour the atmosphere of the place was of the sea salty. There was one hotel, the Carrington, which was common property. It was the best-known hostelry in town, chiefly in consequence of the popularity of a bar-maid there – Nell, by name – who was often known to present half a sovereign to a hard-up customer.

The Cape Horn Breed, by William Jones, who arrived at Newcastle in 1906 in the ship British Isles, contains some other descriptive passages:

More than 60 sailing ships were in the harbour when we arrived. The ships gave the impression of a forest of masts and spars and rigging, in a confused tangle against the skyline, as they were moored three abreast at all jetties on the Stockton side. Every crane berth at the Dyke was occupied, and loaded vessels were moored two abreast to each of the three Farewell Buoys at the harbour mouth near the Nobbys.

The scene was one of intense activity, as ships were constantly being moved across the basin by paddle-wheel tugs, from waiting berths to the crane berths, and thence to the Farewell Buoys to be cleared outwards. These operations were complicated by the fact that almost every sailing ship arrived at Newcastle in ballast. Some coal had to be taken in under the cranes as stiffening before the ballast could be safely discharged. The ship had then to be moved to a place appointed to discharge her ballast, at some point on the foreshore, and had then to return to a waiting-berth, to await her turn again to go under the cranes for a full loading.

While they waited – sometimes for months – for their ships to load at the cranes, the sailors spent their time and money in Newcastle:

On evenings when there was nothing else to do, dozens of apprentices in uniform, with their badge-caps askew at jaunty angles, would parade up and down Hunter Street in Newcastle, past the famous Black Diamond Hotel – the scene of many sailorman’s brawls – and back to the vicinity of Scotts, the busy drapers, whose windows attracted the attention of the miners’ daughters, out taking the evening air, strolling arm in arm in bevies of beauty and charm.

“Many friendships were made, some of them sentimental, but the young ladies of Newcastle were experienced in temporary affairs of the heart, and, when writing notes to their new-found friends in ships, sometimes ended with the sad but realistic words, “Yours to the Nobbys”, i.e., The lighthouse at the harbour’s exit.

Many a time, bevies of Newcastle girls have strolled out along the breakwater to the Nobbys, to wave farewell to ships bearing temporary boyfriends away, never to return.

When it was time to load:

Long rakes of coal wagons, each containing ten tons, stood on the railway sidings with a shunting engine to move them into position. The crane lifted a ten-ton box wagon off its bogie, and swung it over the rail of the ship until it plumbed the open hatchway. There, the pin boss knocked out the staple and allowed the hinged bottom of the wagon to fall open with a crash as the coal cascaded into the bowels of the ship.

Seamen had to stand by to warp the ship ahead or astern as the loading went on. The maze of rigging, and the lengthy yards projecting high over the wharf, made it necessary for the crane to be very carefully plumbed if its swinging jib, with its heavy load hanging from it, was not to foul the gear. So around and around we trudged, first on one capstan then on another, to take up a little slack here, and another there, under the second mate’s bellowed orders.

It took British Isles three days to load, and then the ship was moved to the Farewell Buoys to prepare for its voyage to South America:

The boarding house masters in Watt Street got busy and provided us with a full crew at the Farewell Buoys several days before our departure. In the hustle and bustle of getting ready for sea our only consolation was when the captain returned from business trips ashore bringing letters from our girl-friends, ending “with love and kisses, yours to the Nobbys”.

Many boarding house masters were in cahoots with “crimps” who – along with unscrupulous ships’ masters – preyed on sailors. Crimps lured sailors away from one ship, and were paid by the head to put them on another.

Some captains made money on the arrangement by avoiding the need to pay off the sailors when they eventually returned to their home ports. Even after paying crimps for new crews they could pocket a tidy profit. The money they paid the crimps for their new crews was deducted from the pay of the sailors.

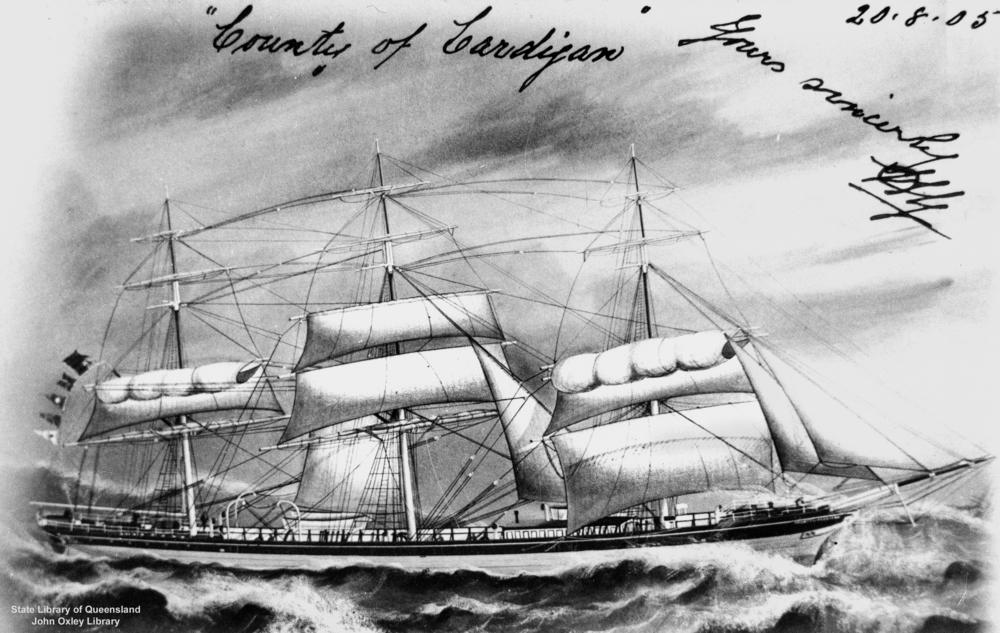

Sir James Bisset, in Sail Ho, a memoir of his early days at sea, described a visit to Newcastle in 1903 in the ship County of Cardigan:

During our long stay in port, the crew and apprentices had leave to go ashore on Saturday afternoons and evenings, with frugal cash allowances in pocket. We went by ferry to Newcastle and promenaded the streets in company with hundreds of other apprentices, eyeing the girls, though usually with little success as demand greatly exceeded supply. On week nights and Sundays we often spent hours in the Seamen’s Mission, which was at Stockton, across the harbour from our berth, and attended concerts and dances and socials organised by the kindly ladies of the Mission.

The crimping industry was well organised in Newcastle. Vessels lying at the Farewell Buoys, near Nobbys Light, were usually short-handed until crimps brought out drink-drugged sailors from pubs on shore, who were easily persuaded by the crimps, on the inducement of a few days’ spree, to desert their own ships and leave it to the crimps to find them another ship.

Newcastle’s most famous crimp was Jack Sullivan, whose cunning at finding ways to extract the lucrative “head money” from desperate skippers was legendary. Slipping “knockout drops” into the drinks of victims was standard practice, and although experienced sailors were preferred, anybody would do. This form of kidnapping was called “shanghaiing” and many men fell victim to it, waking up from a drugged night’s sleep to find themselves far from land and forced to learn the hard way how to sail a ship.

Legend has it that Sullivan – described by those who knew him as a tough lump of a man who had fought his way up from the gutter – once shanghaiied his own brother, and even delivered a corpse aboard a ship when time was running short and no living victim could be found in a port stripped bare of sailors by the demands of departing ships.

Another Novocastrian character whose name has often been linked to crimping was Clarence “Black” Harris (pictured at right), a Barbados-born West Indian who came to Newcastle on a sailing ship in 1895 and lived most of the rest of his life in Bolton Street. Harris always stoutly denied being a crimp but many people chose to disbelieve him, and his name was often used to frighten children with the admonition: “If you keep playing up Black Harris will take you!”

In 1906 the NSW Parliament was told that Newcastle was “alive with pimps”, that seamen were “pounced upon by sharks”, that half of Newcastle’s hotels were dens where seamen were made drunk, where licensees worked in collusion with ship’s masters and most of the boarding houses had taken part at some time in crimping and shanghaiing. The city’s defenders insisted this was “wild talk” and “exaggeration”. Many instances of crimping and shanghaiing at Newcastle were documented over the years. Bisset wrote in his book how, when his ship was ready to sail, “the Captain went ashore and engaged ten fo’c’sle hands, who came off in a crimp’s boat, looking decidedly bleary after their Christmas festivities”.

In August 1889 boilermaker James Rae was approached in the street and offered 15 shillings to help shift a ship from one part of the harbour to another. Rashly, he agreed, and was appalled to find that the ship’s captain had no intention of letting him leave before the ship arrived at Hong Kong. He was forcibly restrained when he tried to escape and even when his employer – who was crossing the harbour in a ferry and saw Rae aboard the ship – raised the alarm there was nothing to be done. Rae’s case was raised in Parliament, but crimping continued unabated for years. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that many city officials turned a blind eye to the practice, and may have been rewarded for their lax attitudes.

Hi Greg, My dad went to sea in sailing ships, he was born in 1901, in around 1917. His great love was the three masted barque the “Shandon”, on which he sailed to both Valparaiso and San Francisco, or on a couple of trips Valparaiso thence to San Francisco and home. Coal out of Newcastle and general cargo on the return leg. He said that 100 King Street, was a sailors boarding house where he stayed on occasions. He also visited Newcastle on the NZ schooner “White Pine”. The “Shandon” was a very fast ship and on a good day could outpace a steamer, the ultimate insult when passing a steamer was to trail a length of rope over the stern (we’ll give you a tow). He continued on the steam until the sale of the Commonwealth Line and upon return after delivering one of the ships to the UK he retired in 1934 and bought a Sydney taxi. He went to sea again in 1942 with the US Small Ships. I have a pencil drawing of the “Shandon” and a photo of the “White Pine” for copying, if they are of any use to you in the future. Cheers, Sue Simmonds

I’d be very glad to see and copy those images Sue. Many thanks for the interesting comment. Greg