In 1939 a vice president of General Motors, Charles F. Kettering, was asked to name the most important research problem in the world. His answer? To find out why grass is green.

Kettering was a remarkable man, one of that likeable breed of far-thinking, imaginative capitalists we see too few of these days. His great enthusiasm was research. Pure research for its own sake. Not narrow, stifled, research of the kind some governments think is the only type worth funding. You can get a sense of the kind of man he was when you read some of the great quotes he left behind.

When Kettering developed electric self-starters for cars he modestly gave the credit to all the other electrical “experts” who were convinced it couldn’t be done. By stolidly refusing to consider the idea, they left the field open for him, he said.

He used to tell a story about the time when it took 17 days to paint a new car. That was because the paint they used dried so slowly. In a factory churning out 4000 cars a day that represented a serious logjam, but when he said he’d like to see the job take about an hour the paint experts called him a fool. Not long after, he saw “a curious lacquer on a cheap pin tray” and when he traced the manufacturer to order a few litres to test on a car door he was told it wouldn’t work because the lacquer dried too fast. Kettering set his researchers to work on the two paints: the one that dried too fast and the one that dried too slow. Within two years they had developed cellulose nitrate lacquers and revolutionised the painting of cars.

Harnessing the power of the sun

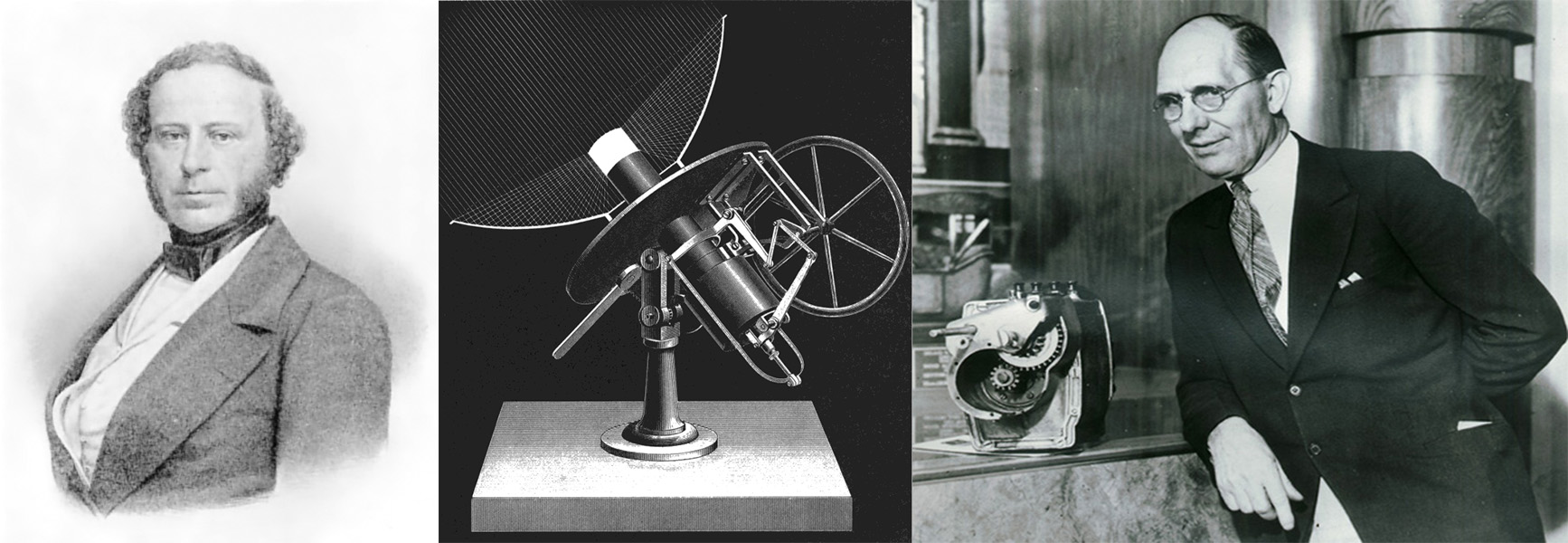

I wish I had a time machine and could introduce Mr Kettering to John Ericsson. Ericsson was born in Sweden in 1803 but spent his later years in the USA. You can read more about his productive life here. He was fascinated by the idea of harnessing the sun’s power and he actually developed some fully functional “sun machines” or “solar engines” which focused the sun’s rays to produce steam, or simply operated as “hot air engines”.

Describing one in a letter to a friend in 1873 he wrote that “less than two minutes after turning the reflector toward the sun the engine was in operation, no adjustment whatever being called for. In five minutes maximum speed was attained, the number of turns being by far too great to admit of being counted”.

Ericsson calculated that “the sun’s rays now wasting their strength on the house roofs of Philadelphia might be used to set 5000 steam engines of 20hp each in motion” or that “64,800 steam engines of 100hp each could be worked with the rays thrown on a Swedish square mile”. As it happens, Ericsson wasn’t the first to think of, or build, solar engines. This interesting article gives some background to earlier ideas and inventions along the same lines.

In the 1860s Ericsson had previously noted that the coalfields of Europe had scarcely begun to be worked but that people were already estimating when they’d be exhausted. “In a thousand years or so – a drop in the ocean of time – there will be no coal left in Europe unless the sun be put in requisition”, he wrote. Ericsson reckoned without oil, of course, but even a generation later a man like Kettering, who owed his career to oil, couldn’t help thinking along the same lines. When in the 1930s Kettering nominated finding out why grass is green as the world’s most important research question he wasn’t joking. Here’s what he said:

A little engine in the green of grass and leaf

“Some little engine in the green of grass and leaf has the mysterious gift of capturing energy from the sun’s rays and storing it. Thence came all the heat and power now stored in coal, wood, oil and natural gas. If we knew that secret we could build engines to transform enough radiation from the sun into heat or chemical energy or electricity to run our machinery. Then the conservation of our natural resources would not be so important as it is now.”

The research he wanted wasn’t funded at the time. We had a world war instead and billions of dollars were spent on research to produce new weapons, most notably the atom bomb whose manufacturers now claim to possess the best answer to humanity’s energy needs.

Ericsson and Kettering are both long gone, of course. Both men would no doubt be fascinated by advances in energy technology in the 21st century, and perhaps disheartened by the role of fossil fuel corporations and their captive governments (especially Australia’s) in trying to hold back renewable energy. But research into a variety of ways of using the sun’s incredible energy output to replace destructive methods of power generation is advancing dramatically despite the troglodytes. I, for one, believe those who follow in the path of Kettering and Ericsson will succeed in finding solutions that not only harness solar energy on a scale that makes it truly viable, but do it without the great harm caused by excessive mining for the raw materials required. I believe that, based on observation, but also in solidarity with this wonderful quote attributed to Kettering:

“I object to people running down the future. I am going to live all the rest of my life there, and I would like it to be a nice place, polished, bright, glistening, and glorious.”