If getting killed by the thousands is glorious, it was glorious in the Ypres battle. My battalion came out 200 strong out of a thousand. It breaks my heart when I think of it.

Private Bob Gibson, Knorrit Flat

By 1917, as fighting wore on in Europe, the British high command was practically in disrepute among sizeable portions of the Allied armies. Commander in Chief Douglas Haig didn’t go anywhere near the Ypres battlefields in late 1917 and criticised the troops for not being able to make and hold territorial gains. Men saw that they were repeatedly sent wading through deep mud against strong enemy defences, and that their casualties were horrendous. In particular, many of those unfortunate enough to be under the command of Haig’s favourite general, the reputedly hopeless Hubert Gough, felt that they were viewed as mere expendable pawns.

It was getting harder for the men at the front line to tell families at home in Australia about the war. The censors, fearing grim detail might hinder recruiting, did their best to keep letters from being too disturbing.

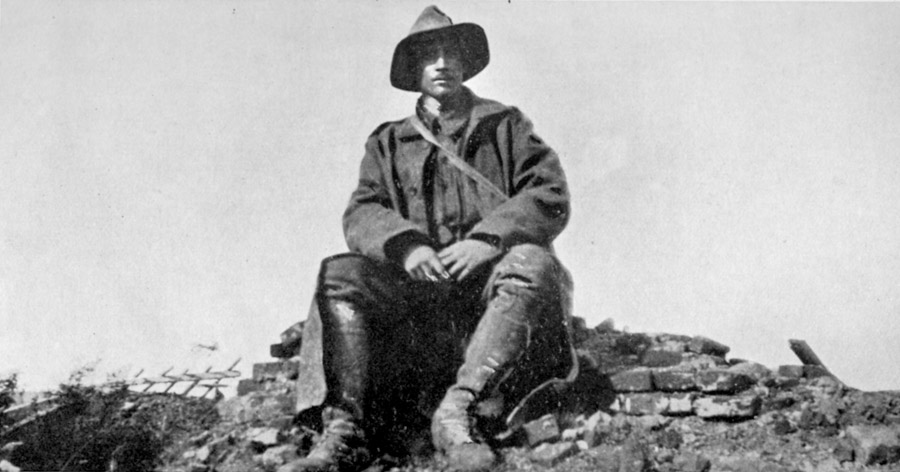

Newcastle soldier Basil Helmore (photo and excerpt from The Western Front Diaries, by Jonathan King), later to become a prominent lawyer in the city, wrote to his parents during a spell in England in August 1917, explaining some tricks to beat the prying eyes:

If there is a blank space at the end of the letter, wet it, because it may reveal something. There is a way of writing so the writing is invisible until the paper is wetted. If you want to know where I am, you should read the letters beginning each sentence in my letter as that will spell out the name of the place where I am. Thus if I am near Ypres I will begin the first sentence with a Y then the second sentence with a P and so on.

In his book Hell’s Bells and Mademoiselles, Newcastle VC winner Joe Maxwell describes an attack at the Menin Road in this sector on September 20, 1917:

We were to attack at six o’clock in the morning and our objective was a pill-box known as Anzac House, probably a mile in front of the existing line of trenches. By midnight we were in the front line on the jumping off tape. A curtain of fine rain muffled everything and the silence of this part of the line held portents of the big things that loomed ahead.

A sudden pop from the German lines breaks the silence. High overhead bursts a rocket, showering down in a splutter of red and green fire.

The scream of shells fractures the quiet. The earth rocks in a dizzy way. Shells scream and whine and burst. Avalanches of earth and sand rush into our trenches. Night has been turned to day by myriads of flaring German SOS signals. Crash follows crash and the acrid fumes of high-explosive clutch at the throat. Then at long last! From behind opens the crackling thunder of our own artillery. A deadly flight of shells sing their way over our heads.

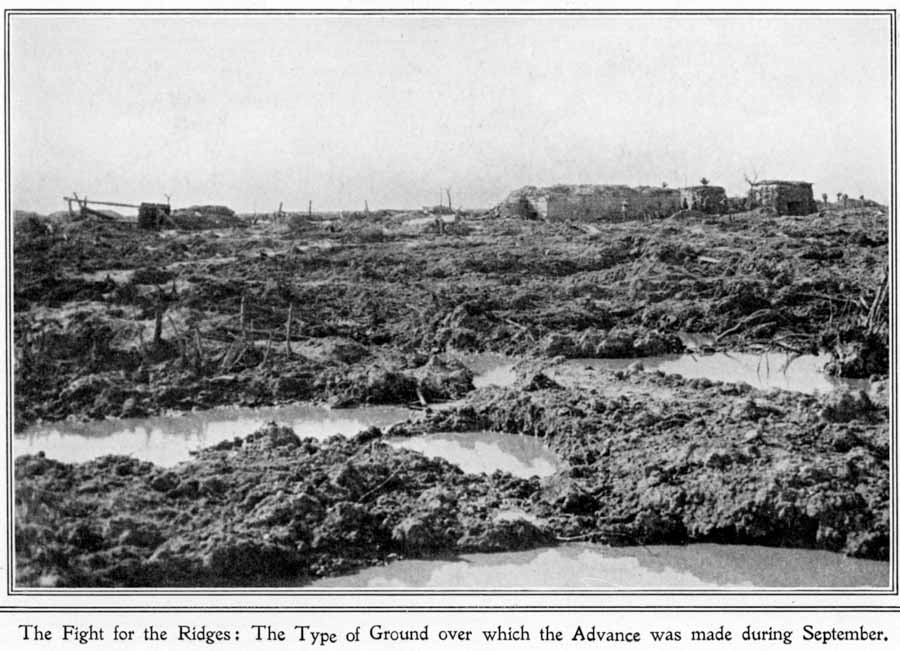

It is zero! Up rises the whole line as one man. Bayonets glimmer in the glare and flashes of shells. Over we go. On we stumbled over ground as rough as a landscape of the moon. When we reached the German front line it had been pounded into a chaos of broken timber, smashed dugouts and riven concrete. Men lay twisted amid the wreckage in all kinds of fantastic and unnatural attitudes. Broken and battered corpses were merged inextricably amid the billowing ocean of mud and the awful wreckage of war.

And among that wilderness of broken timber and shattered concrete squirmed live Germans the colour of the mud in which they wallowed – live men who had lost the power to think.

Their eyes were glassy and had lost all expression. They were sunk in faces that were ashen-grey, drawn and paralysed by the terror of the storm that had burst over them. They stumbled about in the shambles that had once been their front line blindly, helplessly, like men in a state of coma.

The Menin Road action gained about a kilometre and cost 20,000 casualties, including 5000 Australians wounded or killed. The Battle of Polygon Wood, on September 26, 1917, was a similar costly “success” in that it also took ground from the Germans and kept it. The battle plan was knocked askew when the Germans attacked some British troops near the Australian positions and the Australians were called in to defend. The Germans were kept back, and the planned attack began, after a thunderous artillery barrage.

Private Albert Dun, of Bulahdelah, wrote to this father that:

We made an attack on the 26th Sept with 40,000 guns supporting us. We took Polygon Wood and the racecourse and went halfway up Passchendaele Ridge. I saw by yesterday’s paper the Canadians have taken it. They can have it all on their own. We had a great victory. We met the Prussian Guard – the best troops he has – we captured a good few of them. They looked funny coming over with their hands up. Big fellows nearly all over six feet. I saw some great bayonet fights, one in the moonlight it lasted about three minutes but one of our boys hopped in and struck at him with the butt of his rifle. Arthur Piper and Jack Ravell were killed there. I lost a good few of my old mates there. I am a stretcher bearer. We got plenty to do. Our division had six thousand casualties out of 12 thousand. Another chap and I carried out nearly forty cases from 3 o’clock in the morning of the 26th until 8 o’clock on the following morning. We have been recommended for good work but as this is the second time I don’t expect to get anything out of it. The mud is something terrible. It is nothing to go 12 days without having an hour’s sleep at a time.

Polygon Wood gained another sliver of ground and cost another 5770 Australian casualties.

The next step was to Broodseinde Ridge on October 4, 1917. Of this action Sapper Thomas Prince of Newcastle remarked:

That was the morning when the Germans and British had fixed the same zero hour to attack each other. Both forces of shock-troops endured a torrid experience on the tapes in No Man’s Land during the preliminary bombardments. Some sharp bayonet fighting occurred on the Australian front, but the German effort being more in the nature of a local counter-attack, the clash tended to involve the enemy in confusion, which led probably to greater rout as the battle progressed.

Nelson Bay soldier Pte Albert Diemar was with the 36th Battalion, detailed to hold the line while other units went over the top. He wrote to his parents on October 8 (photo and excerpts from the book Anzacs of the Tomaree Peninsula):

It looked a real day of battle. It was raining lightly, dull and very cloudy and the mist was very low over the battlefield. Well, all the men were in position ready for the hop over or waiting for zero time as we term it here and blow me if Fritzy wasn’t on for the same thing. He opened up his barrage about 20 or 30 minutes before us at zero time. I thought he would get his punch in first but he didn’t but he would of got a lovely time if he had as our boys don’t run from the brawl like he does.

Anyhow he must have been going to have a long barrage before he came over, consequently our zero time came. The artillery opened up and down came the shells like a very heavy hail storm on Fritzy’s line. A little later over our boys went. Under Fritzy’s show we were in first going like hell. A little later the prisoners were coming in hundreds. The German prisoners were of a very young class. I saw one near a dressing station, well he only looked a boy of about 15 years old. He looked shocked; well it was enough to shock the best men in the world as our barrage was so heavy one would think that nothing could live under such shellfire. It seems as though some did by the prisoners that came in. A terrible lot of them were wounded. You may not believe this but it’s dinkum: wounded Germans, wounded Australians came in together with their arms around one another helping one another in good and friendly and Germans carried in our wounded in their stretchers and they were very careful with them too.

I never had a talk to a German or heard any of them talking to anyone. You know a lot of them speak broken English. Well the prisoners didn’t want a guide to bring them in, a lot of them came in on their own and followed behind men who were walking down. Well after our chaps dug in Fritz delivered a counterattack but it was useless against us they were repulsed and he delivered several counterattacks in a few hours but they failed. Our chaps could see them forming up and coming up ready for an attack but we got the artillery and machine guns onto them and soon broke the attack so we held on for all the ground we gained and were conquerors of a great battle. Well so much for the battle.

Private Diemar described the scene:

Well the battlefield in Flanders is something awful to look at. One mass of big shell holes, broken-in cement German pillboxes as we call them, also dugouts and all sorts of war material is lying everywhere on the field. Dead men, horses, mules etc everywhere and the smell is something awful bad. But we walk past the dead and take no notice of it at all. At places we may have to hold our nose for the smell is so strong. There are dead Germans in shell holes and the rain has half-filled the holes and they float about. Well this battlefield is miles in depth. Who knows what the ground around this battlefield will be good for after the war. Well, one doesn’t know as it is full of shell holes, barbed wire, pieces of shell casing and it is the most real battlefield I have saw since my service in France.

The Broodseinde Ridge battle gained another 1000 metres or so and cost another 6432 Australian casualties. Those capable of thinking arithmetically could see the numbers didn’t add up to final victory. There was no way the Allies could replenish those losses. Australia certainly couldn’t keep up that rate of sacrifice while relying entirely on volunteers. But the British high command had no better ideas than to keep sending men through the deep mud towards the waiting Germans.

No wonder this area is 100 years later home to the biggest British Commonwealth war cemetery in the world. Tyne Cot cemetery holds 12,000 graves and most of them have no names. On the Menin Gate memorial are the names of 54,000 men who melted into the mud, never to have their remains identified.

Gunner James Dalton wrote his last letter to his sister Ida at Salt Ash on October 4, 1917:

My stars you should see the guns. They are firing over the top of each other in all directions. The men in my crew who have been long at the gun – I mean for the whole summer – go stone deaf after about half-a-dozen shots are fired. The angles, range etc, have to be altered about every 10 minutes and I have the time of my life trying to get my crowd of fellows to hear me. I shouted myself sore-throated this last time. (Dalton was killed just one week after writing this letter).

In the lead-up to the Allied assaults on Passchendaele, the British characteristically flung newly arrived conscripts into the battle with scarcely time to get used to the shocking conditions. Around Passchendaele unknown numbers of men drowned in stinking mud.

Hunter VC winner Joe Maxwell described fighting near Ypres on October 13:

Over Westhoek ridge, down the gully beyond and on to the ridge overlooking Passchendaele we shuffled through the . . . blasted region peopled by the dead.

A multitude of thunders mingled in one paralysing roar, belting on the ear and brain like relentless hammers . . . Wet, heavy clods of earth flew in the air, slapped one in the face, filling the eyes with mud, and thudded heavily against bodies. Fragments of shell whirled past with a vicious whistle. Panting moans rose to the right and left as those shell fragments bit into human bodies.

It seemed an eternity before we reached the front line, and when we reached it, it was some minutes before we knew it . . . Living men and battered bodies were engulfed together in the waves of earth and mud flung up by this terrific fire. Blackened and blood-stained men crawled out of the chaos of mud and filth with the dead rolling into the cavities from which they emerged. It was a valley of agony.

In that valley of agony was the 13th Battalion, with not many of its Gallipoli originals now remaining. The author of the battalion’s official history wrote:

On the 15th we were bombarded with heavy gas shells, both of the mustard and phosgene varieties, necessitating the constant wearing of the uncomfortable respirators. It was the battalion’s first experience of a really tremendous gas bombardment.

The worst effects of the gas were delayed, but terrible, drastically reducing the fighting capacity of the battalion. Of the 416 who went into Zonnebeke on the 14th 309 remained to come out on the night of the 21st, and of these not one was able to speak above a whisper, that even being agonising in most cases. Throats, lungs, eyes and noses were soon raw, blistered and intensely itchy, and acute vomiting could be heard on all sides, made the more painful by the inflammation. That week left more post-war troubles than perhaps any other week in our history. It would have been better had several of these gas casualties paid the full price up there on the foggy, soaked and poisonous Passchendaele swamps.

British losses in the push on Passchendaele were 13,000, 4200 of them Australian and 3000 New Zealanders. Wounded and dying from both sides lay on the muddy ground for days. Many died from exposure since there weren’t enough medics or stretcher bearers left alive to help them.

Sapper Thomas Prince, originally from Newcastle, called Passchendaele “the nadir of frightfulness” and described part of the battlefield after fierce fighting for a German concrete pillbox:

Broken rifles, bayonets, stick bombs and machine guns; German shrapnel helmets, haversacks and other accoutrements; bodies with all their limbs, others without a head, a leg or an arm; lumps of indefinable shape with tattered shreds of cloth adhering; and all coated with slimy grey mud. Dead faces grinned horribly in derision at the sun peeping through a hole in the clouds on the sorry result of human folly.

Private Diemar was among those wounded, and he described his experience in a letter to his family:

I was wounded by a sniper in the left leg, about four inches above the knee. It broke the bone, so down I went useless; later I was pulled into a shell hole. A chap put a dressing on it. A few hours later the stretcher bearers came; they put a rifle on my leg for a splint, one of the bearers was slightly wounded. So then they could not carry me out so they put me in a deeper shell hole and left me. I was there all night on my own. Next morning the Huns were carrying their wounded from all around me. They saw me but went to their men. So I thought I had better get, so I put all the bags I could around my leg to keep the mud out of the wound. Then when I got a chance I made a bold splash for our own lines. I had to crawl on my back. Well I crawled half a day when I met a chap wounded in the hip. So he said he would come along with me. We set off, me crawling on my back and he on his side. We looked bright birds scratching along. Well we crawled till dark then we stopped in a trench that night. Next morning we set off again. By this time we could see our chaps digging a trench. At last we got close enough to make them hear us calling for stretcher bearers so a few of them came out and got us into our own lines.

Sergeant Thomas Dial, a coalminer from West Wallsend, was at Passchendaele with the 34th Battalion.

It rained all night, and we were up very early on the 11th of October which turned out to be a fine day. So we pitched our tents and dried our blankets, thinking that we would be camped there for a further few days. But we all had to fall in at 4.30pm with battle order and get our issue of bombs, sandbags, picks, shovels and our 24 hours ration.

Sgt Dial and his comrades made their way forward to the “assembly trench which in reality was large shell holes, and we had to stay there until about 5.30am on the morning of the 12th October when the barrage would open”.

So we all put our great coats on as it was commencing to rain heavily, and had a few winks of sleep . . . Eventually our artillery and machine guns opened up, and we all hopped out of the trenches. After we had gone about 100 yards we were all being bogged in mud and water as far up as the waist. Our rifles were only a hindrance, for when I had a chance to fire I found it was hardly possible to open my bolt to reload.

Some men gained ground, but their position was impossible and they were ordered to retreat.

At this moment all the men started to move back, but as it was a very bad way to go back we got the men to move back in small parties so that they would not be a very large target for the enemy artillery fire. When they had reached the original front line we again dug in. I may as well state that it was raining all the time.

A few days later I opened a paper and saw a very large heading of the Australians latest gains at Passchendaele, but all we gained was a big casualty list, for in my Company 18 came out of 118 that had been in it.

Bob Gibson recorded his opinion that:

If getting killed by the thousands is glorious, it was glorious in the Ypres battle. My battalion came out 200 strong out of a thousand. It breaks my heart when I think of it.

Canadian troops took over the push for the unimportant village and won it eventually on November 10, at the cost of another 12,400 casualties.

The casualties on both sides from the battles in the Ypres district in late 1917, and especially the fighting near Passchendaele, were horrendous.

The Australian War Memorial states that “Maitland’s Own” 34th Battalion suffered 50 per cent casualties. Ben Champion missed the worst of Passchendaele, having been wounded and sent for hospital treatment. Champion’s unit went to the shattered town of Ypres, then forward again into support trenches.

Here in these support dugouts we were badly gassed, through which we lost three men. It was a most unpleasant camp – we were constantly drenched with gas shells and our clothes reeked of it.

The line is held by scattered posts, which are camouflaged. Fritz is too sensible to occupy this swampy area so it is left for us.

After their stint in this part of the line, the medical officer of Champion’s unit ruled 67 per cent of the men unfit to march “owing to gas and sore feet through the line slush”.

So ended 1917 with the bloodbath of Passchendaele and the onset of another freezing winter. Of the great players in the war, the French troops were practically at the end of their tethers, worn down by horrific casualties. The Russians had quit, freeing numerous German divisions to move across to oppose the Allies on the Western Front and the British were struggling to plug the gaping holes in their ranks with conscripted boys hurled against their wills into the mud and gore. The much-vaunted Americans were arriving in numbers, but were yet to contribute in a significant way.

The Colonials – Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians – were now the rock-hard but ever-shrinking core of the Allied forces on the Western Front.

In the words of Salt Ash Gunner James Dalton:

I have reluctantly had to come to the conclusion that the colonial troops are without doubt the best fighters we have on the line. They have done what the Tommies have failed to do too often to allow any other conclusion. It is an artillery war here now though: simply a matter of massing batteries to smash away at each other. The side that can replace its casualties in men and guns quickest and keep it up longest will win.

Indeed, by the beginning of 1918 many Australians, both overseas and at home, had lost faith in the ability and goodwill of the British high command and were agitating for the five Australian divisions to be placed under Australian command. There was an understandable feeling that the British commanders were uselessly squandering Australian lives, and a desire to take control of the situation away from these increasingly unpopular generals. As a result of much agitation, the Australian Corps became a reality from January 1, 1918. This was not happily agreed to by the British, but the Australian losses had become political dynamite and the Australian government could no longer afford to let the English generals have their way. British Secretary of State for War, Lord Derby, wrote to General Douglas Haig as follows:

I am having a great deal of trouble about [the colonial forces] at the present moment, especially with regard to the Australian Corps, and I am afraid, for various reasons, we must look upon them in the light in which they wish to be looked upon, rather than in the light which we should wish to do so. They look upon themselves, not as part of the English Army, but as Allies beside us.

This new reality didn’t suit the British, but it almost certainly saved many Australian lives and perhaps even helped turn the tide of the war.

You do not mention Captain Jeffries VC a Newcastle resident who was killed at Passchendaele. He is commemorated at his alma mater Newcastle Boys High School