Stand by your glasses steady, for each man who takes off and flies. Here’s to the dead already; three cheers for the next man who dies.

Toast proposed by British World War 2 aircrew following the death of a comrade.

In the foothills of the Barrington Tops, in NSW, pieces of a wrecked Lockheed Hudson aircraft are a lonely monument to the three men who died in the 1954 crash, including World War 2 bomber pilot Doug Swain DFC.

The wreckage is also a monument to a bold, unusual and somewhat ill-starred venture by The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper to boost its postwar circulation by operating its own air deliveries of newspapers to the northern parts of NSW. Sydney Morning Herald Flying Services started in 1947 with ex-air-force planes and cost 10 lives in its six years of operation, making a barely perceptible impact on the masthead’s circulation figures.

Surplus bombers at rock-bottom prices

According to Gavin Souter’s history of the Fairfax publishing business, A Company of Heralds, the service began in February 1947 and was headed by experienced commercial and wartime pilot Harry Purvis. Purvis was sent to Scotland to buy aircraft and found two near-new ex-Royal Air Force DC3s. A few months later the service bought three surplus Hudson bombers from the RAAF at rock-bottom prices. The service was based at Macquarie Grove, a wartime aerodrome near Camden, and the planes took off before dawn, either landing at airstrips to drop off the bundles of newspapers or dropping them on specially prepared drop zones. Souter wrote that the dropped bundles usually bounced four times, and once a bundle knocked a policeman off his bicycle near Grafton.

A former employee of the service, John Laming, described the dropping procedure: “The bundles were wrapped in hessian and then either dropped through a chute cut into the bottom of the aft fuselage of the Hudson or slid off a hinged platform through the rear open cargo door of the DC3.” “In both cases the co-pilot would be down the rear of the aircraft to operate the chute in the Hudson; or to physically lift the platform in the DC3 so the bundles would slide down the inclined platform into the slipstream. For the DC3 the co-pilot would tie himself to the airframe to minimise the chances of him falling overboard in turbulence,” John wrote.

John wrote that many of the pilots and crew members were former air force men, as were most of the ground crews. John Laming was 17 when he started working for Sydney Morning Herald Flying Services, and he later went on to have an illustrious flying career of his own. An article by John that covers his time at the service can be found here.

The service’s first fatal accident happened in its eighth month when Hudson VH-SMJ crashed near Muswellbrook while on a trial dropping flight, killing pilot John Hoskins and second pilot Edwin Conner. According to John Laming: “It was discovered that when the co-pilot was at the rear of the aircraft during the turn toward the drop-zone, the centre of gravity of the Hudson went beyond the aft limit, causing the Hudson to stall. At that low altitude, there was insufficient room to recover”.

Ten fatalities in six years

On New Year’s Day, 1950, another Hudson (VH-SMK) crashed shortly after taking off from Camden, killing pilot Dick Cruickshanks and co-pilot Bruce Purvis (nephew of the service’s manager, Harry Purvis).

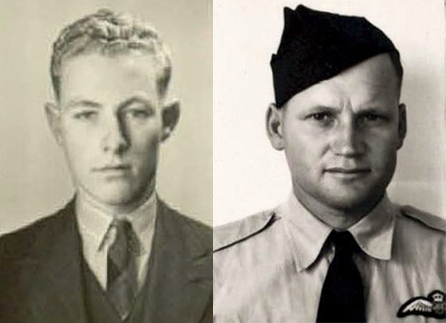

On October 12, 1950, the service’s flagship DC3, VH-SMH, crashed at Bungulla, south of Tenterfield, killing pilot Richard F. Hartnell and co-pilot B. Keith Cridge. Keith Cridge had served in the RAAF during World War 2, training in Australia and Canada before serving in the UK, reaching the rank of flight lieutenant. He married in Sydney in January 1948. His daughter, Dianna Crebbin, contacted me after reading this post and described how she and her mother and other relatives had visited the crash site on the 50th anniversary of the accident and met people who had been present at the scene. Although she was an infant at the time of the crash, Dianna said it was an event in her life that she had never quite come to terms with. She said her understanding of the accident was that the plane had been flying low in dense fog, following the the railway line that runs at the foot of the escarpment near Tenterfield. The pilot turned too soon, realised his error and tried to climb too late to avoid clipping an obstacle and crashing on the plateau near Bungulla.

Another fatality occurred when a cleaner, Tony Pinner, was hit by the propeller of a DC3 in a hangar at Camden and killed instantly.

By 1952, Fairfax shut the air delivery service down, mostly for economic reasons. Harry Purvis had resigned and Doug Swain was moved to a desk job – which he hated. At 35, he appeared to feel his career was over, and he pushed Fairfax to restart the service. The company agreed, and Hudson VH-SML was put into service to deliver copies of the afternoon Sun newspaper to northern NSW.

Tragically, the plane crashed on the first delivery flight on September 14, 1954. Apart from the pilot, the Hudson was carrying first officer Alistair Sydney Cole-Milne and a passenger, Captain David C. Burns. According to Souter: “Swain took off from Mascot at 2pm bound for Taree, Kempsey, Armidale, Glen Innes and Tamworth. There was a positioning signal from him near West Maitland, then silence.” Newspaper reports at the time said the signal came from Belford, between Greta and Singleton, at 2.37pm. According to John Laming, the Hudson was not approved for flying in bad weather, and the crash probably occurred due to Captain Swain trying to keep below cloud in mountainous country.

Two Grafton airmen, Garth Monroe and William Wetherton, who were flying from Newcastle to Tamworth at the time, reported seeing a Hudson circling at 2500 feet, west of Scone, about 4pm. A Singleton schoolteacher said he saw a plane resembling a Hudson flying low over the town at 5.45pm, and Henry Martin, of Branxton, saw a plane flying low over Belford at 6pm. But according to official records, the crash must have come only about eight minutes after the flight’s last positioning call.

Search failed to find the missing plane

A search failed to find the plane and the searchers eventually gave up. Then, 15 months after it had disappeared, at 11.10am on December 22, 1956, two Butler Air Transport pilots in a DH 114 Heron, Captain Bill Jenkins and L. Beales, spotted the wrecked plane about 10km north of Chichester Dam. Captain Jenkins saw something glinting in the sunlight and circled the site before confirming that it was the wreckage of a Hudson. The plane had crashed about 6m from the top of a hill at the foot of the Barrington Ranges. Coincidentally, Bill Jenkins was a former colleague of Doug Swain at the Herald Flying Service.

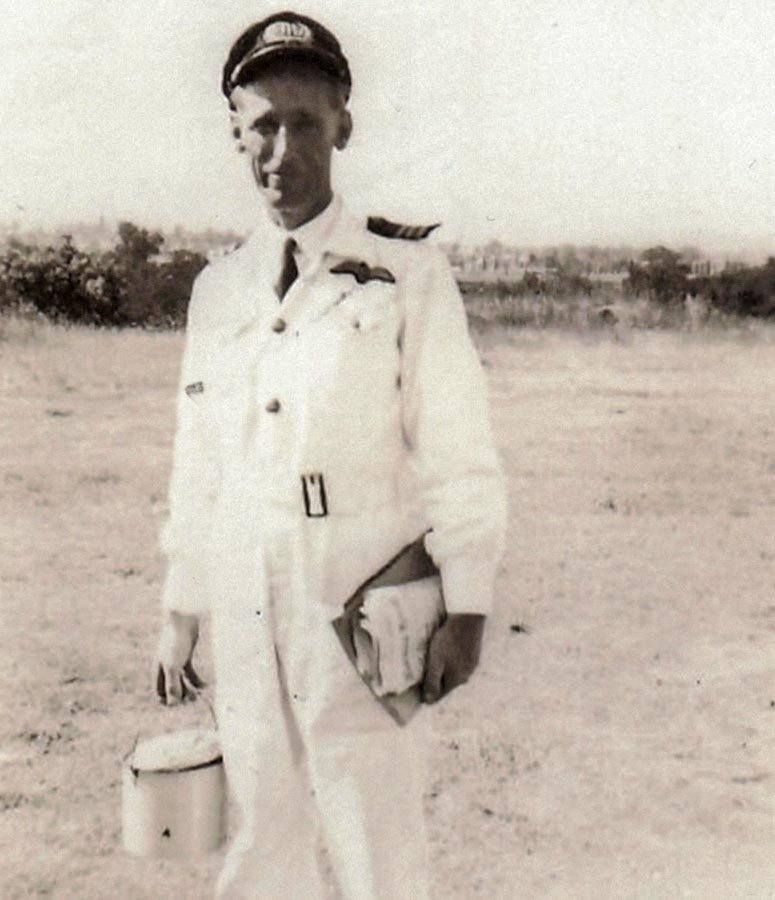

Doug Swain’s death ended an illustrious flying career. In the Royal Air Force during World War 2 he and his navigator, Mike Bayon, had flown more than 50 missions in Mosquito bombers as part of the elite pathfinder group. Both men earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for their efforts.

According to John Laming, Doug Swain retained some of his wartime daring and displayed it at times in his newspaper delivery job. “When he was flying the Dakota, Doug Swain would drop a single rolled-up Sydney Morning Herald to some friendly farmers who lived on country properties among the mountains near Tamworth. He would circle the house then drop half-flap, reduce the airspeed to 95 knots and come in low over the farmer’s house. The co-pilot would slide open the starboard window and on the order from Doug, throw the paper down inside the arc of the starboard propeller. In return, boxes of fruit would be waiting each week at Tamworth aerodrome as a gesture of thanks from the farmer. Back at Camden, Doug would give the apples and oranges to the ground staff. It was a happy arrangement,” Laming wrote.

An article by John Laming that covers Doug Swain’s accident can be found here.

A year before his fatal crash, Doug Swain had been co-pilot aboard a Mosquito aircraft on a flight from Australia to England to take part in the London to Christchurch Air Race. The pilot was Aubrey “Titus” Oates DFC. The plane struck monsoon weather in the Bay of Bengal and was forced to ditch. Both men were rescued unharmed.

When news of the discovery of Swain’s wrecked Hudson broke in 1956, Oates flew his own Tiger Moth to the area and landed on a ridge 10km from the crash site. Next day he helped police find the wreckage by circling in his plane. A police party led by Inspector W.L. Jefferson, of Maitland, reached the scene from Dungog about noon on December 23, 1956.

In 2007 Doug Swain’s son, Richard, visited the scene of his father’s crash and placed a commemorative plaque at the spot. He had been four when the accident happened. In an article in The Sydney Morning Herald, Richard Swain described finding large pieces of the plane still lying in the thickly timbered scrub.

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************

I am the daughter of B Keith Cridge who was Co Pilot of the plane that crashed in October 1950. So interested to read this article

Dianne Crebbin (Cridge)