Sir Francis Drake in 1580 (At least some people say so)

Assured his name eternal fame by finding the potato.

Old song I learnt at school

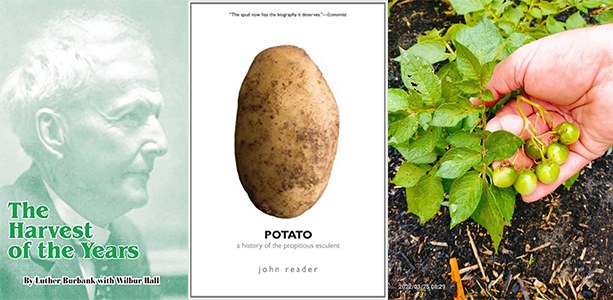

Actually Drake didn’t find the potato at all. Peruvians had been cultivating potatoes in the Andes for thousands of years before Europeans turned up and took some home. And the Spanish certainly beat Drake to it, sometime in the late 1500s. Be that as it may, the humble spud certainly changed the world, as you can read in this book.

And, while the potato changed the human world, humans also changed the potato just as they have changed a bewildering array of plants (and animals) whose characteristics they have moulded to their needs and wants. One way the potato has changed over the millennia is that it has become a little lazy about sex. Humans do such a great job of perpetuating the potato by planting its tubers that potato plants don’t really need sexual reproduction. Which means they don’t need fruit. Nevertheless, they can and do make fruit, which contain seeds. They just don’t do it very often.

Even avid gardeners don’t see many potato fruit, and when they do they are often quite surprised. A few weeks ago I noticed somebody on a Facebook gardening group sharing photos of potato fruit and wondering what they were. This instantly reminded me of a famous story about American plant-breeder Luther Burbank – truly one of the greatest exponents of moulding plant characteristics in human history.

Burbank summarises the story in his fascinating autobiography, The Harvest of the Years.

In New England we grew large quantities of potatoes but they were generally small of a reddish colour and few of them could keep us. It required no genius to know that if a large, white, fine-grained potato could be produced it would displace the other varieties and give its discoverer a great advantage over his competitors. I tried crossing with poor results, for the hybridised blossoms produced no seed. And selecting led me nowhere. Then I found a potato seed ball! I use an exclamation exclamation point. That is because – well – it was what an astronomer would use if he discovered a new solar system. A potato seed ball was not unheard of, but it was a great rarity and I couldn’t learn of anyone who had done anything about the event even when it occurred. I did something. I planted the seeds in that ball. I had 23 seeds and I got 23 seedlings. From that whole number – although there were many that were an improvement on any potato then grown – I selected two that were amazing, valuable and a distinct type. They were as different from the old early rose as the beef cattle of today are different from the old Texas Longhorn. It was from the potatoes of those two plants: carefully raised, carefully dug, jealously guarded and painstakingly planted the next year, that I built the Burbank potato. And it was from the Burbank potato that I made my beginning as a plant developer. Not only did the new potato prove to me that nature was ready to cooperate and collaborate with man but it made me a small name and paid me some small amount of cash.

Burbank knew that the seeds of plants contained vast possibilities. In their genetic library they carried potential attributes accumulated over countless generations of lived experience. That was Burbank’s great insight, along with his realisation that this library of possibilities – coupled with the selecting agent of environment – was capable of transforming organisms in radical ways. He would grow acres of trees then select just one or two and burn the rest, closing in on the characteristics he wanted that tree to express. He was patient. He even bred spines out of cactus, thinking to make a drought-proof cattle fodder.

He lost me, in places in his book, when he started making value judgments about certain human types, drawing a long bow from his plant experiments, I thought. But all the same, he was a remarkable person and his book contains a lot of valuable insights and thoughts that deserve deep consideration. Despite being rather anti-religious – preserving his wonder and awe for nature rather than any man-made deities – Burbank got close to Buddhism at times, especially when he declared that he believed in “the immortality of influence”.

Anyway, back to potato fruit. The potato plant is one of the nightshade family, related to tomatoes, and the fruit are somewhat tomato-ish. The berries vary in appearance and characteristics, with some apparently rather toxic and others quite nice and safe to eat. This site discusses the subject at length.

It’s interesting to reflect that this “humble” vegetable, so firmly pressed into the service of humanity, still retains links to its wild past and will, given a chance, produce variants that might be world-changing. Unexpected flowers bear unlooked-for fruit with unforeseeable results.

Might be some lessons there . . .