SOMETHING about the photograph kept drawing Bill Lieb’s eyes back.

The picture was in our book, Recovered Memories, published in 2011 as a companion volume to our earlier book, Newcastle, the Missing Years.

At first glance it was just a pleasant picture of two young boys sitting on the wharf at Newcastle Harbour, sometime in the 1930s. But after looking for some time at the photo Bill, then 87 and now deceased, felt his skin prickle with sudden recognition.

Across the harbour, opposite the boys, berthed against the Lee Wharves, was a ship. An unmistakeable ship with no funnels, four masts (one of them blackened by soot) and a distinctive bow and stern. The ship could only be the one on which Bill went to war as a merchant seaman in 1941 and the one that was torpedoed out from underneath him off the coast of Africa in 1942.

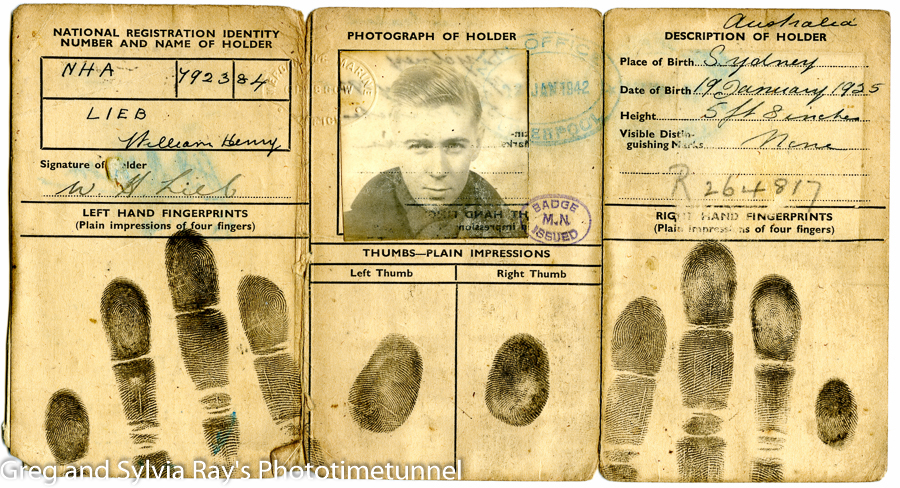

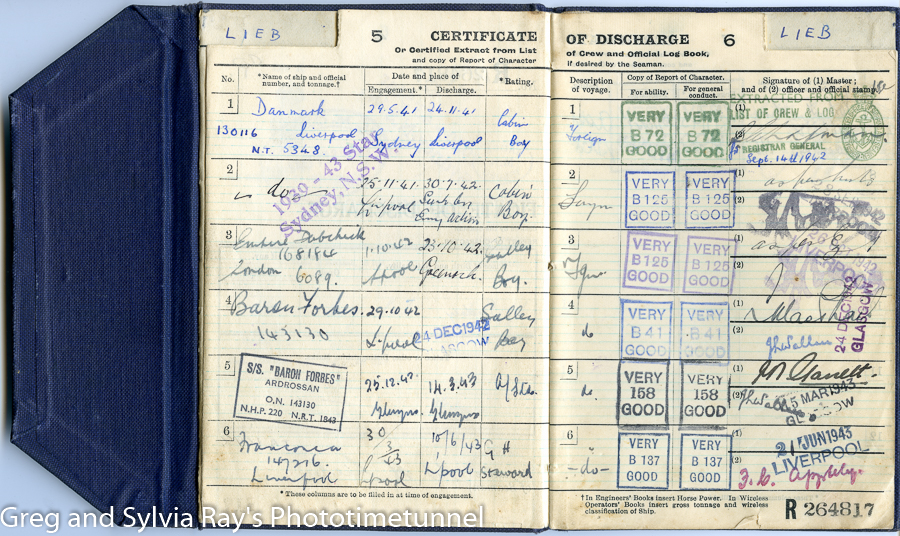

Sure enough, it was the Danmark, which visited Newcastle in March 1937. Its reappearance after so many years took Bill on a voyage of memories that began when the Newcastle youngster signed up to his first ship, the William McArthur, in 1939. Bill was just 14 and signed on as a deck boy on the ship, carrying R. W. Miller’s coal from Newcastle to Melbourne.

“I didn’t last long on the Willy. I was too young and I quit,” Bill said.

But in 1941, with World War II under way, he decided to go to sea again, this time as a 16-year-old cabin boy on the Scandinavian-built trading ship, the Danmark. The Danmark was Bill’s passport to a world of experiences, some good, some bad.

He recalls the ship with affection, and remembers especially the finicky diesels that would cough up a huge cloud of black soot every time they were started, painting one of the ship’s masts an oily black.

Bill arrived with the Danmark in Liverpool in November 1941, in the middle of the long and brutal U-boat battle of the Atlantic, with Germany striving to sink as much merchant tonnage as it could to put England out of the war.

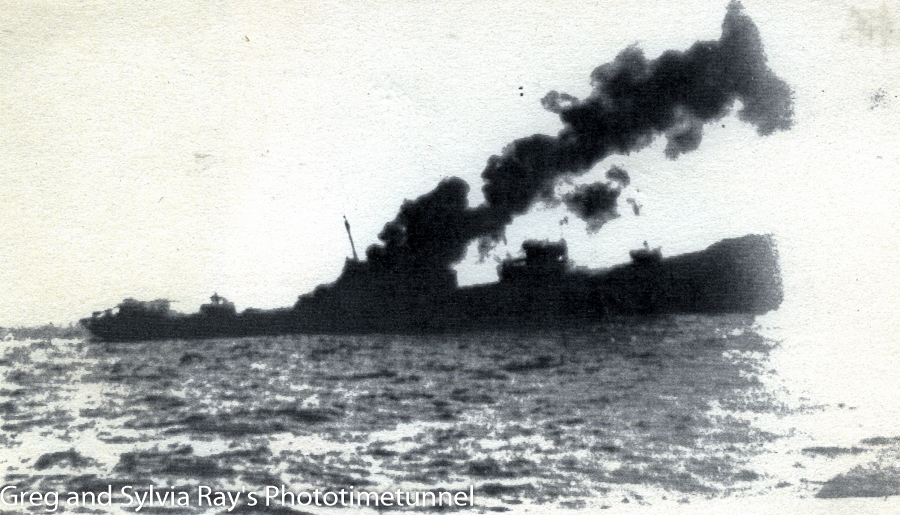

“We were in ballast out of Capetown, on our way to Trinidad, when we were attacked by a submarine, 900 miles west of Freetown, Sierra Leone,” Bill said. That was July 30, 1942.

The submarine was the U-130, and it gave the defenceless Danmark all it had. A torpedo strike provided the mortal wound, but the U-boat pumped dozens of five-inch shells into the stricken ship as it settled and the men raced to abandon ship. Nobody in the crew got more than a few scratches, but Bill remembers the terror of trying to get off in the surviving boats as shells tore through the burning structure of the sinking ship.

The U-boat skipper didn’t target the men in the boats and, miraculously, they only spent four or five hours in the water before being picked up by the Norwegian motor tanker, Mosli. It was exceptionally brave of the Mosli‘s skipper to stop and rescue men in an area just vacated by a U-boat, a fact that isn’t lost on Bill.

“She was fully laden with furnace oil for escort ships and would have made a big fire if she’d been hit. But they took the chance and saved us. I still get choked up about it to this day,” he said, with a catch in his voice.

Back in England in October, Bill signed up to a decrepit old tub called the Empire Dabchick. Twice the old Dabchick tried to sail the Atlantic as part of a convoy, but both times its engines failed and it was forced to return to port.

“We told the skipper we’d had enough and we wouldn’t try to go to sea in her again,” Bill said.

Next time the Dabchick sailed, it was with a different crew, all 48 of whom were lost without trace when the ship was sunk, not far from its destination in Canada, on December 3, 1942. Bill joined the Baron Forbes instead, as a galley boy.

He was lucky to survive another attack on February 28, 1943, when his old nemesis, the U-130, attacked the convoy in which he was travelling.

The commodore of the convoy was aboard the Baron Forbes and Bill said he was nodding good morning to this chief officer when they heard two thuds and realised that two ships in the convoy had been hit by torpedoes.

“They were loaded with ore or some heavy freight because they just ploughed straight under water within seconds as we watched.

“Two firemen who had been sleeping aft came running along the ship shouting that they’d heard a screaming sound from the water below the ship. I told them to calm down. That was the sound the torpedoes made. They were driven by compressed air and if you were down deep in the ship you could hear them pass,” Bill said.

Another two explosions and another two ships of the convoy were sunk, giving the U-boat captain four kills from a single spread of torpedoes.

As it happened, one of the torpedoes passed directly underneath the Baron Forbes.

“We were riding unusually high in the water because we were carrying a big cargo of cork. It was so light and buoyant we were more than a metre above our usual marks and the torpedo passed under us and hit the next ship instead,” Bill said.

He finished his merchant seaman service as a general hand and steward aboard the liner Franconia, then returned to Australia in 1943 to join the air force.

He was trained as a flight mechanic and served at the Rathmines seaplane base on Lake Macquarie, near Newcastle, NSW, until mid-1945 when he was transferred to Queensland.

“I was being trained in jungle warfare when the war ended,” Bill said.

In his latter years Bill became interested in learning about the U-boats and the men who used them to such devastating effect against merchant shipping. His research uncovered a photograph, taken by the crew of the U-130, of the Danmark, belching smoke as it began its death-dive. And another, of the skipper toasting his success on the submarine’s conning tower with a glass of champagne.

“About a week after the U-130 attacked our convoy it was sunk by an American destroyer,” Bill said.

Bill’s postwar career was driving trucks, a pursuit that lacked the excitement and danger of the wartime merchant marine.