THE Royal Australian Air Force was just cutting its teeth on jet fighters when the Korean War broke out.

Ron Guthrie was one of a handful of Australian pilots with experience flying Vampire jets out of Williamtown RAAF base – near Newcastle, NSW – so he was an obvious choice to join the United Nations campaign against North Korea. It was a fateful posting that led to the young warrant officer becoming the first Australian jet fighter pilot to be shot down in the Korean War.

Guthrie had joined the RAAF in 1943 at the age of 18 and qualified as a pilot when he was 19. His World War II service was as a staff pilot flying Fairey Battle aircraft. After the war he served as an air traffic controller but kept his hand in flying Kittyhawks and Mustangs, as well as Dakotas. By the time the Korean War broke out he was called back to fly fighters and was the low-level aerobatics demonstration pilot in the newly formed 75 Squadron. He was posted to 77 Squadron in Korea in March 1951.

He became one of only 30 Australian prisoners of war in Korea. He staged a daring escape attempt, was recaptured and finally released after two years of appalling treatment at the hands of the North Koreans and Chinese.

After his release he returned to the RAAF as a flying instructor and he retired as a Squadron Leader in 1980.

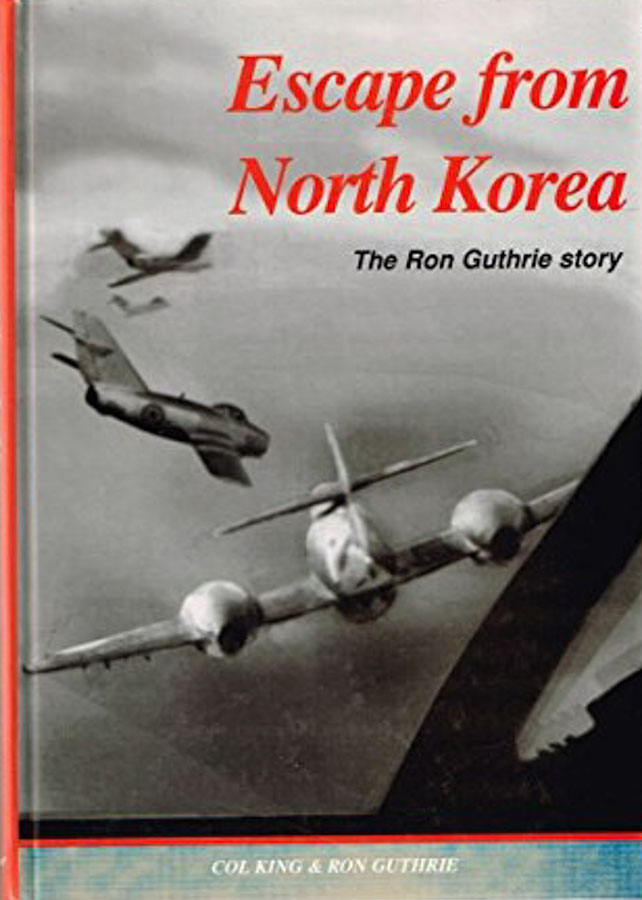

I interviewed Ron in April 2011, when he was aged 85. He had written a memoir, Escape from North Korea, which made it clear that his captors didn’t lag far behind the Japanese of World War II for brutality and lack of concern about international conventions on the treatment of prisoners.

Ron Guthrie’s Korean war story began in 1951.

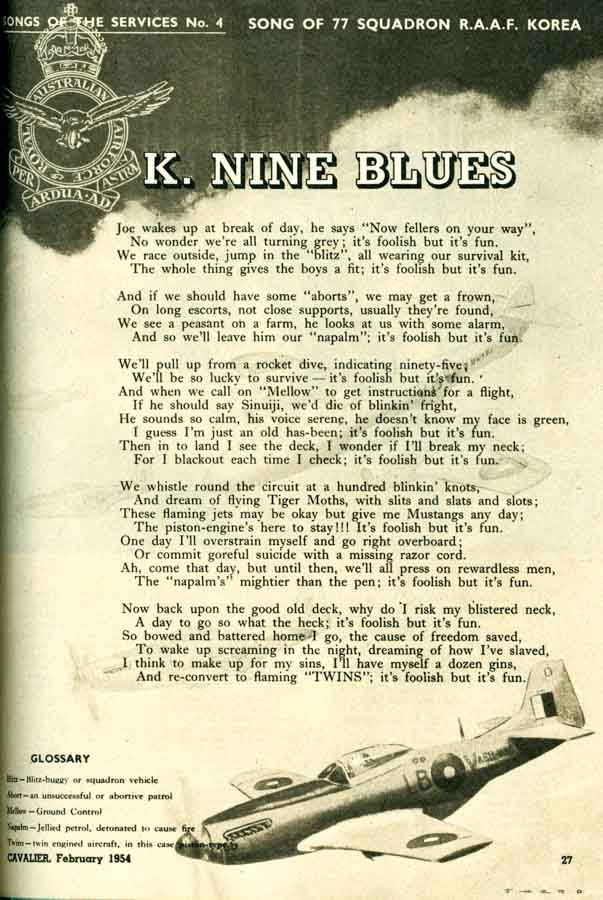

For an air force still struggling to leave the propeller age, Korea was a deadly destination. Australia’s 77 Squadron flew its first Korean missions with World War II-era Mustangs. A fine fighter in the mid-1940s, the Mustang was totally outclassed by the early 1950s and it was obvious a jet replacement was needed.

The pilots wanted American Sabres, but the US didn’t have any to spare for its junior ally. The second-best option was a British two-engined jet, the Meteor. The Meteor was a big improvement on the Mustang, but even it was becoming obsolete and the Australians were soon to find it was hardly a match for the Russian MiGs being flown by the enemy.

Guthrie, who was genuinely fond of the Meteor, is brutally frank about its shortcomings. “It was well-armed but too slow,” he said. “It was a subsonic plane with straight wings. At 40,000 feet it handled like a bag of manure.”

By the end of the war, 54 of the squadron’s 90 Meteors had been lost – mostly through anti-aircraft fire – 38 personnel had lost their lives and seven pilots had been taken prisoner.

Top cover for American bombers

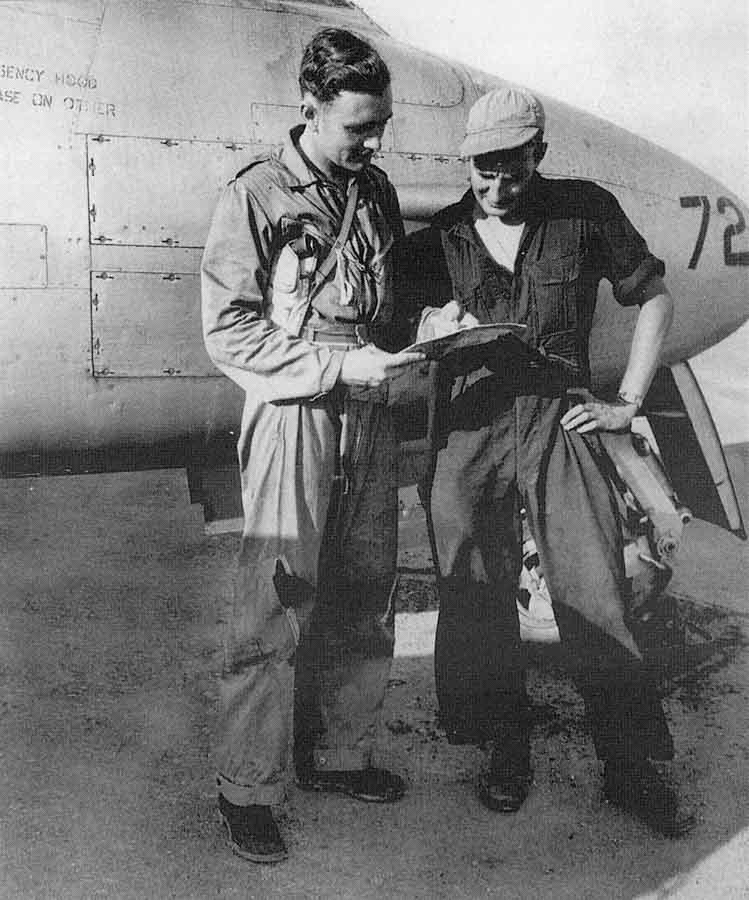

Guthrie’s moment of truth came on August 29, 1951, while flying “top cover” for a formation of American bombers. It was his 15th mission. As an experienced pilot, Guthrie was assigned the hazardous formation position of “tail-end Charlie”, behind his seven colleagues.

Flying at about 39,000 feet as a shield against high-flying MiGs, Guthrie’s Meteors soon found themselves under attack. Startled by tracers “like glowing ping pong balls” shooting past his wing, Guthrie threw his plane into a turn. He’d been hit, but still managed to get a MiG in his sights and fire, watching pieces fly off the faster Russian plane as it dived out of sight.

But while Guthrie was firing, another MiG was attacking him from behind and he felt his Meteor shake convulsively “like a load of bricks had fallen onto my rear end”. His plane began to fall and roll simultaneously and Guthrie realised he’d have to eject. Three times he tried to pull the ejector handle, each time waiting for the plane to turn upright in its spin. On the third time he succeeded, but forgot to tuck his legs into the proper eject position, suffering a painful blow to his knees.

Half-hour parachute descent

At the time his ejection set a height record, and it took more than half an hour to descend almost 12 kilometres to earth. As Guthrie got close to the ground North Koreans took pot shots at him, tearing holes in his parachute. He landed in a rice paddy between two women who mistook him for a Russian MiG pilot and took his hands, only scattering when more bullets started to fly around them. Guthrie used his service pistol to wound a soldier who was running at him and firing, but he was quickly overpowered and taken prisoner.

Over the next months Guthrie was to experience a variety of prisons, ranging from a tiny wet hole in the ground to a Chinese interrogation camp.

None of Guthrie’s fellow Meteor pilots had seen him shot down and it was months before his squadron and his family learned of his captivity. Shortly after his capture he was taken to a Chinese “re-education” camp where he declined an invitation to take an interest in communism and to share information about his aircraft and his squadron. His lack of co-operation led to him being handed by the Chinese back to the North Koreans.

Eventually his mother was sent a propaganda booklet on behalf of the Chinese, extolling the splendid treatment that United Nations prisoners were allegedly receiving. Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett – who had earned his reputation in 1945 by defying US authorities and telling the true story of the atom bomb blasts in Japan – demolished his good name in many eyes by helping the Chinese sell their false story about the good treatment of prisoners in Korea.

“Burchett was taken by the Chinese to a few places and apparently persuaded by them,” Guthrie said. “When we prisoners found out what he was saying we were furious. We’d have strung him up if we’d had the chance.”

Prisoner of the North Koreans

The true position of most prisoners was bleak. In one prison Guthrie shared with scores of hapless Koreans, inmates were forced to sit motionless and silent for 17 hours a day under the unforgiving eyes of vicious guards while his body was assaulted by hungry lice.

Episodes of forced labour, savage interrogations, starvation and brutal forced marches followed, with winter temperatures well below zero and the sad spectacle of fellow prisoners wasting away around him. Fear of slow death helped Guthrie and some fellow prisoners decide on an escape attempt from the notorious Pyongyang Interrogation Centre. They bravely cut a hole in the timber wall of their prison, propping a one-legged comrade against the hole by day in a risky bid to hide the evidence.

Travelling by night, but slowly fading from hunger and fatigue, Guthrie and his two companions made a beeline for the coast. Disaster struck when the escape leader, Englishman Tony Farrar-Hockley (later to become General Sir Anthony Farrar-Hockley) was recaptured, leaving Guthrie and American pilot Jack Henderson to continue. They made it to the coast, but stage two of their escape plan – stealing a boat and sailing to UN-held Cho Do Island – eluded them.

Caught and horrendously beaten, the pair was returned to the infamous Korean torture camp named “Pak’s Palace” after its sadistic commandant. About 40 prisoners, most of them frail, sick and multiply injured, lay hardly moving in the building where the two escapees were placed. Guthrie thought one man was wearing a cream-coloured jumper, but in reality he was thickly coated in lice. That prisoner died the same night Guthrie first saw him. After several horrific days at Pak’s Palace Guthrie and his fellow prisoners were ordered to make a 320-kilometre forced march to the Yalu River. Many of the 40 men could scarcely walk. Their guards stole and sold the food that had been provided for the prisoners on the journey. Not surprisingly, many prisoners died.

Release at last

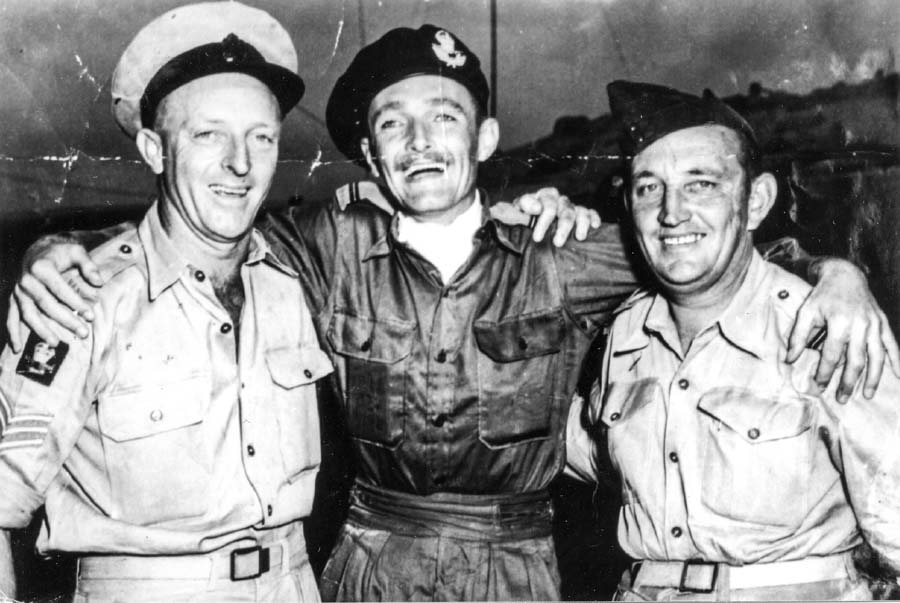

The new camp was under Chinese control. Conditions were bad, but not as shocking as they had been in establishments run by the North Koreans. Guthrie was in Chinese hands in July 1953 when a truce was called in the war and a prisoner exchange arranged. After some false starts and an apprehensive wait, Guthrie’s turn came to be released. It was September 3, 1953. He wrote:

As I placed my foot unsteadily on the steps I was immediately approached by two of the biggest American military policemen I had ever seen. These kind men took me gently under each arm – just as my legs buckled. They helped – almost carried – me down the steps and through a beautiful archway bearing the printed words: ‘WELCOME GATE TO FREEDOM.’ Tears rolled down my cheeks.

Guthrie was thin and emaciated, but alive. Irrational hopes that he might be reunited with old mates at 77 Squadron were dashed when he realised that “they were all long gone – either killed or time expired and replaced”.

Guthrie was among the last prisoners released from North Korea. The last group was freed on September 6, 1953: a so-called 105-strong “bonus repatriation group”.

Elation at release was tempered by the knowledge that 944 acknowledged prisoners remained behind in North Korea where it is presumed they slowly starved and died. Some inkling of the scale of North Korean abuse of prisoners can be gleaned from the fact that of the 7190 American servicemen who were captured, approximately 3000 died in captivity.

After the war he continued his flying career with the RAAF, rising to become squadron leader before retiring in 1980. Nightmares of captivity stayed with him for years, but with the help of his family he put those behind him.