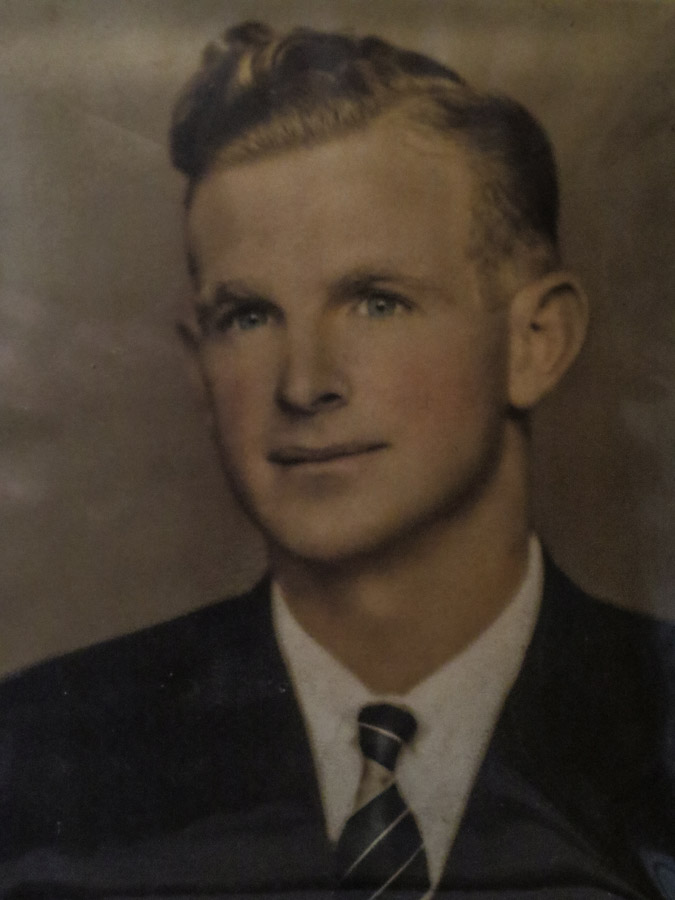

Harry Boyle was 36 when the big flood struck his dairy farm at Swan Reach, near Hinton, in the Hunter Valley of NSW. The former Australian Army commando had been back from the war in New Guinea for 10 years and had settled down to farming with his wife, Elsie, and his two young sons, Peter and Geoff, aged 10 and 11.

Harry had seen his share of floods on the Hunter River and its tributaries, and when he heard another was on the way in 1955 he wasn’t too worried. The family spent time lifting their furniture and belongings as high as they could (a back-breaking job), then the boys moved the horses and most of the cattle to higher ground. In the past the water, when it overflowed the river, steadily filled up about 2000 acres of flat land between the watercourse and Harry’s place, giving him time to get to high ground. “I spent a few hours trying to get my cows to high ground but they mucked about on me so much I ended up giving up and deciding to get the wife and kids to safety,” he recalled.

Explosion as the levee collapsed

They’d barely started to prepare when Harry heard a muffled explosion from the direction of the Paterson River and within minutes a roaring torrent was raging between the house and the high ground, trapping Harry and his family. The noise was the collapse of the Hinton-Wallalong levee, heralding the rapid rush of floodwaters towards Harry and his family.

“I had a little boat so I got the family into the hayshed – no flood had ever been that high – and was making trips taking food across to them – guided by ropes – when the current belted me against something and stove a hole in the boat. I jammed a shirt in the hole to plug it and went to the hayshed,” Harry said. The boat was pushed into a corner of the shed, with a baling tin handy.

He put his family on a big hay dray that stood about 2m off the ground and as darkness fell he climbed up beside them. His favourite cow – a prizewinner at numerous shows and as tame as a dog – was tied to the dray wheel beside them. “About midnight I put my hand over the edge of the dray and felt water on my fingertips,” he said. “The noise was deafening. There was logs and all sorts of rubbish banging into the shed walls. I turned my cow loose, found the boat, bailed it out and put the family into it.” All this was done in pitch darkness. “No starlight or moonlight could reach the earth. It was the darkest night of my experience,” Harry said. By the time he found the boat, by sense of touch, in the shed corner, water had already risen to the top of the dray.

The cow tried to get in too, and Harry, with great reluctance, planted a foot on its forehead and pushed it away. Harry’s son Geoff recalled being afraid that the desperate beast would overturn the boat, and the effort needed to push it away. The family heard its frantic lowing and bellowing as it floated downstream.

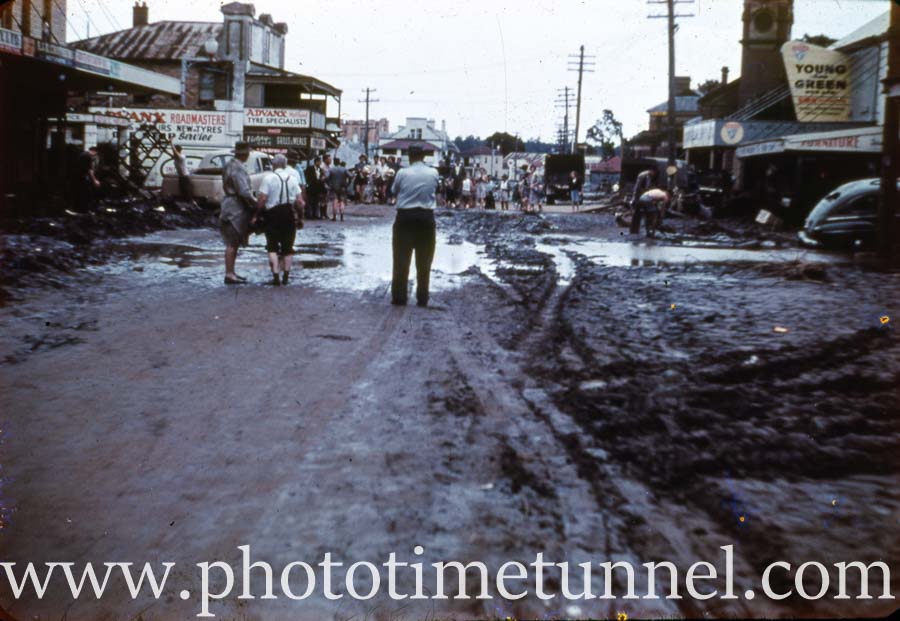

When dawn came, Harry bashed a sheet of iron from the hayshed with an axe he found and the family clambered onto the skillion roof where they sat nervously hoping the shed would stay intact. Only the roof of their house was visible beneath a sullen, leaden sky and in the midst of a wide angry expanse of filthy fast-flowing water. Harry’s wife, who couldn’t swim, was deeply worried. “Two very brave men in a floodboat with an outboard motor came and rescued us,” Harry said. The men were Bill Mann and Leo Burgess, who had been sent by neighbour Mrs Gibbs, who insisted the Boyle family was still at their drowned farm.

A neighbour – Mrs Grimmond – took the family in and gave them food and dry clothes before they moved, with about 50 other people, to the Hinton School of Arts Hall. Geoff remembered sleeping in the hall with his brother. “We were close to the doorway, and somebody had propped an old door sideways across the opening because a wandering pig kept trying to get in. They ended up killing her and we ate her,” he recalled.

Wartime mate swam and waded from Morpeth to Hinton

The next night, while the water was still high and scores were still stranded at Hinton, the Boyle family received an unexpected visitor. Harry’s old wartime comrade, Joe Compton, suddenly appeared in the middle of the night with his mate Mick Williams and a bag of oranges.

“Joe was manager of the Commonwealth Bank at Gosford, on the Central Coast, and he was worried, wondering if his old mate Harry was all right. It was hard getting any news at the time, and there were all sorts of rumours,” Geoff said. So Joe and his mate caught the train as close as they could get to Maitland, then made their way to Morpeth. “They asked directions in the middle of the night, then followed power poles, swimming and wading until they got to Hinton. Uncle Joe woke us up, shook our hands, said he was glad we were all OK, then he turned around and swam back again. He was back at work at the bank next morning,” Geoff said.

When Harry came back to his property after the water receded his stock was lost and his house was full of stinking mud. Most of the furniture had washed away. Strangely, a fish in a bowl on a table survived the ordeal, rising to the ceiling with the water, then returning in an upright position to the table when the water left. A big sow had blundered into the house and drowned, adding to the chaos and smell, and it took Harry half-a-day to extricate her remains.

And his favourite cow? In a bizarre twist, she floated all the way to the Cosmopolitan Hotel at Raymond Terrace where she landed on the top storey. A farmer recognised her, told Harry she was alive and he got her back. He sent his sons with a halter to collect her, and somehow they got her down the slippery stairs of the hotel and took her home.

In 1999 Harry declared his most enduring memory of the ordeal was of his two young sons comforting their frightened mother through the long dark terrifying night, assuring her that they would get her to dry land.

******************************************************************************************************************