It was June 10, 1926, and the Brisbane Limited train was on its way from Sydney to Wallangarra with 143 passengers aboard. Among the passengers was a member of Australia’s federal parliament and a number of members of the cast of a J.C. Williamson touring production of Katja the Dancer.

At about 9.50pm the train, with eight carriages hauled by two engines – a heavy NN type and an AD class in front – had just passed Aberdeen station without stopping and was crossing the wooden viaduct approaching the steel bridge over the Hunter River to the station’s north.

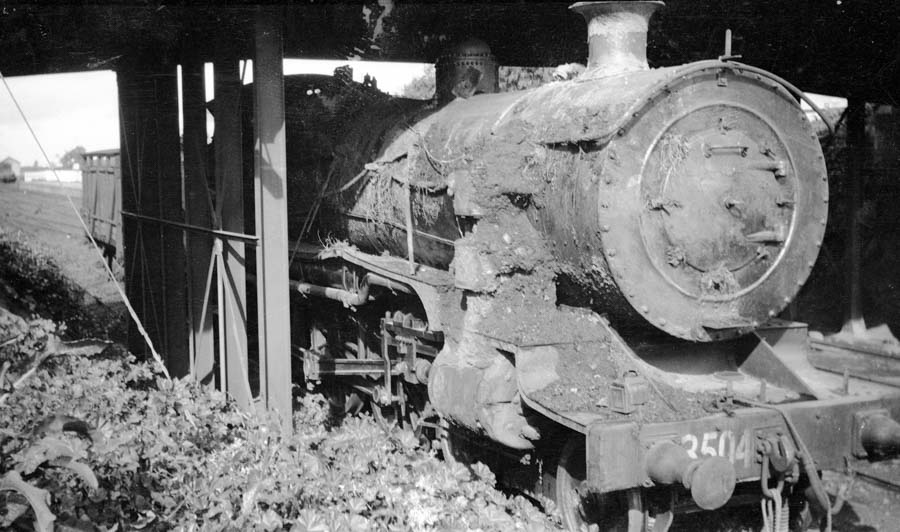

Passengers, most of whom were preparing for bed, felt a bump. Accounts of the accident say the first engine stayed on the tracks but the second somehow turned on its side, left the rails and partly buried itself in the embankment. The guard’s van turned over and the next carriage in line, a second class passenger car, was broken in half. Three more carriages turned on their sides and hung suspended from those following, which remained on the track.

Four people were killed in the smash and many more were injured.

It was observed by some that, had the derailment occurred a few seconds later on the big steel bridge across the Hunter River – which was at the time swollen by recent heavy rain – things would have been much worse.

As word of the accident spread, rescuers raced to the scene. A newspaper reporter, who got there in the early hours of the morning, described what he saw: “Large flare lamps served to illuminate the jet-black darkness of the night. In the valley alongside the Hunter River one caught sight of a terrible jumble of engine and carriages, surrounded by great litters of steelwork, wire and splintered wood. In the deathly silence moved rescuers, together with some passengers who had escaped, looking for signs of bodies or trapped passengers. Bedding, mattresses and clothing were strewn about among the knee-deep clover of the river bank”.

“Help came quickly from various parts of the countryside. In the early stages axemen were mostly in demand and throughout the night their ringing blows were heard as they cut their way through the woodwork of capsized carriages to rescue passengers imprisoned within. The night was bitterly cold, and roaring fires were lit along the railway line around which lay injured passengers awaiting transit to Scone and Muswellbrook hospitals.”

One of the injured was Miss Marie Burke, a member of J.C. Williamson’s Musical Comedy Company who, although herself suffering some serious lacerations from broken glass, insisted on helping search for and rescue her fellow passengers. Among those she helped rescue was her fellow theatrical player George Warde Morgan, who was reported to have a fractured spine and pelvis, serious internal injuries and broken bones in both legs. He said that when lifted out on a stretcher the pain was so acute he couldn’t even bear the weight of a blanket.

Told he would never walk again, Morgan defied the predictions and returned to his stage career – albeit with a noticeable limp. The following May he and Miss Burke both returned to the stage in a production of Frasquita, earning loud applause when he told the audience that he owed his life to his co-performer. “But for Miss Burke I should not have been here today. Though injured herself she, by sheer strength and willpower, pulled away the carriage seats and doors which kept me down,” he said. For years afterwards, the tenor held a special annual dinner in Miss Burke’s honour.

Marie Burke was a British character comedian who was also trained in opera singing. She was born Marie Rosa Altfuldisch, later Holt. She went on to have a highly successful career in films and television.

In the days following the crash, thousands of sight-seers came to view the crash scene, arriving by the car-load from all over the state. Remarkably, the track was re-opened within days, a feat made possible by the presence of concrete piers erected near the site when the duplication of the line was contemplated – but not proceeded with – a decade before.

A coronial inquiry into the deaths found that the deaths were accidental, but added the rider that: “The condition of the permanent way at, and immediately preceding, the scene of the derailment was not in a condition such as should have been maintained safely to carry an engine of the NN class travelling at any speed exceeding 35 miles an hour”. Some people blamed the NN-class engine, claiming the class had a tendency to roll, and the cause of the accident continued to be debated for years.

The photos in this post were taken by Henry James Nicholson, who was part of the crew of the “Craven” railway rescue crane. The negatives were loaned to us for scanning by his daughter, the late Joan Duffell.