The loss of the SS Catterthun off Seal Rocks, NSW, in August 1895 is a story that has captured many imaginations. Thousands of gold sovereigns, en route to China, went to the bottom, ensuring the wreck has remained a magnet for treasure-hunters. When I read contemporaneous press accounts of the disaster I’m struck by the terrible fate of so many of the passengers – especially the women and children – and can’t help wondering whether some of the ship’s officers and crew might have done more to help save more lives.

“Don’t panic”: fatal advice

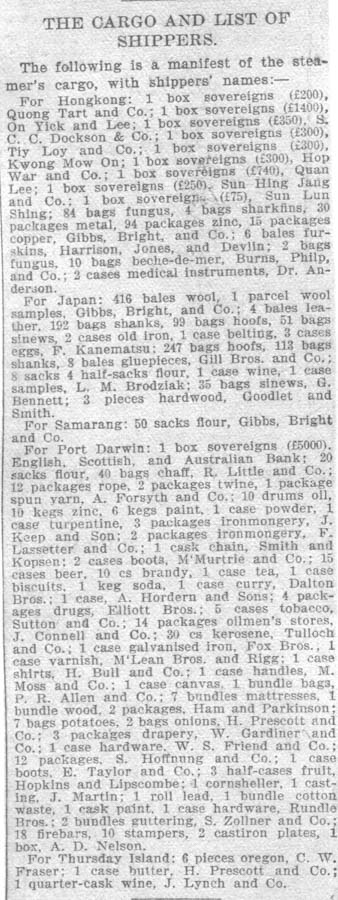

The passengers were asleep below decks when a double-crash reverberated through the ship’s metal plates. It was after midnight, August 6, 1895, and the SS Catterthun, on a routine run from Australia north to China and Japan, was heading past Seal Rocks, NSW with about 80 passengers and crew aboard. Only a handful of passengers were travelling in style in the ship’s costly cabins. Most – the Chinese passengers – were travelling in the less expensive steerage berths. A lot of export cargo was aboard too, along with several boxes of gold sovereigns worth about £10,000.

The crash felt and heard by those aboard didn’t seem to make sense. The Seal Rocks were a well-known hazard, lit by a strong lighthouse, and the ship’s captain and officers were very familiar with the route they were travelling. Witnesses reported that the second mate, A. W. Lanfear, had altered course four points to the east when he took over the wheel just after midnight. The course should already have been well-clear of danger, and the course alteration should have put matters beyond doubt. But it was a squally night, with heavy seas, and it is clear now that the ship was off its safe course.

One of the passengers, Dr A. H. Copeman, told how, earlier in the evening on its way up the coast, the ship had been swept by huge waves, one of which had washed out his cabin. The seas were rough enough to keep the female passengers in their cabins at dinner time, but Dr Copeman said one of the ship’s officers had told him that things would improve once they passed the Seal Rocks in the early hours of the morning.

When the crash came, Dr Copeman left his cabin and rushed up to the lower bridge where he said an officer told him the ship had struck a rock. But he got the impression that the ship might not have been badly holed: it was still moving ahead much as it had before the impact, and it seems in retrospect that some believed the ship might be run in on some shallows where the people aboard might manage to escape.

Passengers slow to learn the truth

Members of the crew were quickly ordered to get to work, preparing the lifeboats for launching, but few passengers seem to have had the benefit of learning as much as Dr Copeman discovered from his short visit to the bridge. Awoken by the crashing sounds, cabin passengers made their way to the saloon, wondering if they should be trading their nightgowns for lifejackets. A handful of women were among the cabin passengers, and they were looking for reassurance or advice. In the saloon, which communicated with the deck through a doorway, they were met by a fellow-passenger, Captain J. Fawkes, who was on his way to Thursday Island to bring a steamer down to Sydney. Captain Fawkes told the women not to panic. At first, when he had heard and felt the crash against the Catterthun’s hull he had been concerned. But since the ship seemed to be continuing steadily on its way he concluded that it had simply been hit by some big waves and that everything would be all right. He told the women to go back to their cabins, and he did the same. When awoken again shortly after this and ordered on deck, he reported being told by the chief steward that the female passengers were dressing.

Meanwhile those of the officers and crew on deck were still trying to get the boats ready for launching, a difficult and dangerous exercise. The ship was starting to sink and was developing a list to starboard. By the time the passengers below were told to get on deck it was already too late for most. It was a struggle to find lifebelts, much less work out how to wear them. According to the account of one of the ship’s stewards, Wong Lun Sing, he had been shaken awake in his bunk above the engine room and and ordered on deck. He said he tried to get lifebelts on the female passengers and open the saloon door, which was by then jammed closed by the weight of water. After a struggle he got the door open and water flooded the saloon. He made his escape, but he said the passengers in the saloon refused to follow him. They would all have drowned there. Their fate would have been shared by the women and children in steerage, none of whom survived.

Another cabin passenger, Mr T. C. Crane, of Shanghai, also described the scene in the saloon. He had already been on deck after the impact awoke him, but despite seeing the crew working on the boats, had not been able to learn the truth and so had gone back to bed. Called shortly after to go on deck, he said he had been unable to find his lifebelt. A steward fetched one for him, but he gave it to one of the women, who were also unable to find their own in their cabins. Mr Crane saw Wong Lun Sing force the door open and he followed him onto the deck, leaving the women and some other men behind.

The end came quickly

The end came quickly. The surviving boats were washed away from the ship, which sank in a rush. Few managed to get aboard the boats. Few, indeed, had enough warning to be in a position to even make the attempt. Even though the captain and the officers on deck at the time of the impact knew what had happened, the passengers were left in ignorance so long that it became impossible for them to wake up, get dressed, find and put on a lifebelt and get on deck. It’s true that there wasn’t much time, but it seems to me that much of what they had was wasted. In the event just 26 people – most of them members of the crew – survived in a single lifeboat. Though it was holed and overloaded, the boat managed to get around the point of Cape Hawke where they found the boat of a Greek fisherman lying at anchor. The fishermen took the men aboard and towed the boat to safety.

When news of the disaster reached port authorities in Sydney and Newcastle, fast tugs were sent out to look for more survivors. The ship’s No.3 lifeboat was found, but it contained only the body of a dead man. A couple of days later the empty No.2 lifeboat was found, and later still the captain’s gig – again empty – was recovered.

Once the horror of the accident had been absorbed, attention turned to finding the wreck and recovering the valuable gold aboard.

The Catterthun had been built in Sunderland for the Eastern and Australian Steamship Co and it was launched in 1881, the same year the company lost the SS Brisbane – with no loss of life – near Darwin. On its fatal voyage the Catterthun was heavily laden with cargo, and insurers were anxious to recover some of their loss, if possible. But while searchers quickly identified the rock the ship struck – about 4km south south east of the Seal Rocks lighthouse – and located the wreck shortly after, it was found to be lying in water too deep for successful salvage with the diving technology then available. It was found in water about 30 fathoms deep (about 54m),

Diver Arthur Briggs got down about 25 fathoms, but could only dimly make out the ship’s shape beneath him, and he reported that the pressure was too great for his gear to withstand. He said he would make the attempt the following year, if better equipment could be imported. The insurers paid for two suits of better gear, and the salvage attempt began in May 1896. A detailed description of the effort can be read here.

Many of the coveted sovereigns were recovered, but not all. The divers agreed that they had reached the limits of their own endurance and the capabilities of their suits. That meant that some gold was left behind to lure treasure-seekers for years to come. A fascinating account of modern-era attempts, and of general dives on the site with scuba gear, can be read here, on Michael McFadyen’s scuba site.

This e-book about the disaster, by Chris Craig, looks like an interesting read.

This documentary, on the subject by Max Gleeson, also seems interesting.