A few weeks ago my sister-in-law gave me a pile of old magazines that had once belonged to her father, Frank Norris, of Kotara in Newcastle, NSW. These magazines, titled Shipbuilding, Ship Repair and Services, didn’t seem promising reading material, but knowing as I do that interesting information might be found almost anywhere, I took them home and started leafing through them.

Almost immediately I was rewarded by the discovery of a fascinating article, by John Broadhouse, about his voyage from Scotland to Australia in 1924 aboard the Koondooloo, a British-built vehicular ferry that was destined to spend years running from Newcastle and to Stockton, and to end its days on an ill-fated attempted tow up the NSW coast.

Read more about the Koondooloo and other Newcastle vehicular ferries here:

I like Mr Broadhouse’s article so much I am reproducing it in full below.

BY HARBOUR FERRY ACROSS THE OCEAN, by John Broadhouse

At the beginning of 1924, I was a young colonial seaman, little more than a boy, “on the beach” in London, and, owing to the post-war depression, unable to ship home.

During a cruise of the docks one morning, I met a fellow colonial, who, while shouting me a frugal lunch in the “Missions to Seamen” in the East India Dock Road, said that a ship-broking firm not far from Aldgate, was sending out to Sydney “some kind of a small ship – a steam-punt of sorts.” He himself was staying on the English side for a while, however. Personally, after two years, I found few attractions away from my own country, so set off in haste to interview the firm. As a result I found.myself and my seabag, which was slack-bellied, at Hawthorn’s shipbuilding yards in Leith.

The ”steam-punt of sorts” resembled an oversized, decked-in pie-dish. It squatted far below the wharf. From its middle a glorified stove-pipe pinned a small street-car to the deck. This sea-anomaly was a ferry, built to carry motor-cars across the Sydney Harbour. I “repaired on board” and reported.

Both ends appeared to be sterns. Which end, then, would go first? I settled the question when I found her name, painted in bold lettering, “Koondooloo, Sydney, NSW”, on one end. Obviously the stern. Hence, I now knew port from starboard. Did we, her first crew, feel inspired with confidence in her sea-going appearance? Well I ask you!

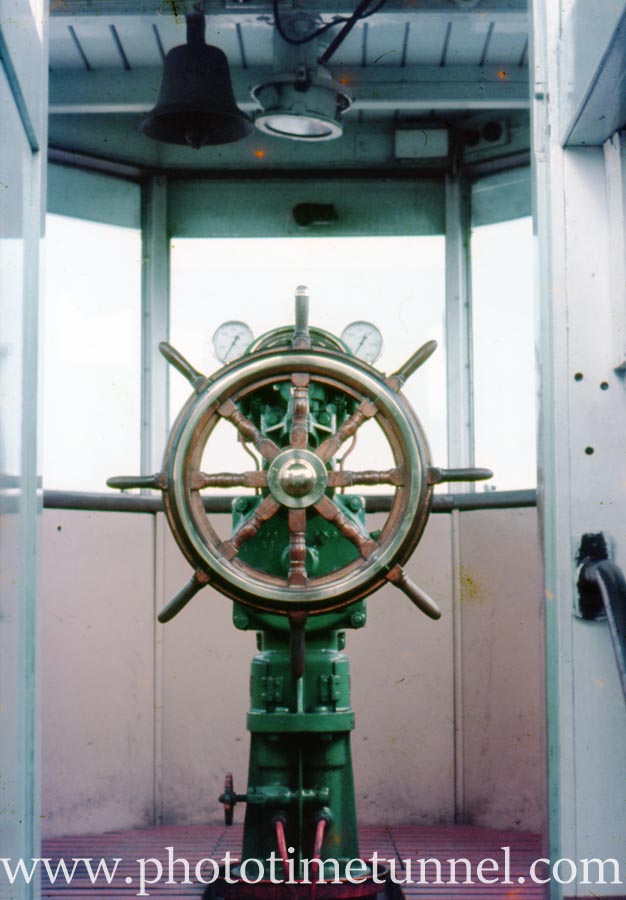

As her below-deck bunkers held only 50 tons of coal, two breakwaters had been erected on deck, for’rd and aft, and filled with, roughly, an additional 100 tons. The navigation was to be carried out from one wheelhouse, of which there was one at either end of the glass deck-house. The other was fitted up as a chartroom. This was another indication as to which end was to go first. Of some 500 tons, and about 200 feet in length overall, she drew approximately ten feet of water. The door inscribed “Captain” was in the glass deck-house, which was rapidly being boarded up. This was the only cabin deluxe, and ultimately, when running in Sydney, was to be used as a ladies’ rest room. The remainder of the crew were housed below under the coal on the foredeck.

Two scuttles, which had originally graced a German destroyer, gave access and sole light and ventilation to these quarters, one scuttle to those of the sailors, firemen, and cook, the other to the domicile of the rest of us, namely, officers and engineers, who were berthed two in a room with a small messroom adjoining. The galley was on deck. It resembled a large tank, and was securely lashed between the scuttles.

We carried no radio

The next day, April 29, 1924, with the rest of the crew, I signed articles, and on that day began the most memorable three months of my sea career – wallowing across the world in a lumbering harbour ferry. Everything was soon squared up for sea. Our crew mustered fifteen: master, two mates, three engineers, five sailors, and three firemen. With the casting-off of mooring lines, and a clanging of the engineroom telegraph, the “K” slipped unobtrusively from her berth and was soon heading into the Firth of Forth. Our troubles were to commence even sooner than we expected, for we ran into a stiff south·easter shortly after clearing St. Abbs Head, our bluff square “bows” thumping into a heavy head sea, and shipping tons of water, which threatened to dislodge the coal on the foredeck. By easing down the engines, and heading her a couple of points out of the wind’s eye, she began to behave better. However, she was going to demand nursing, for by midnight she was cutting capers, due to wild steering, a difficulty which we soon overcame by shipping the hand steering-gear. When about off Hull, we ranged up alongside a fishing boat, and sent a letter ashore to the London agents, informing them of our slow progress, for it must be remembered that we carried no radio. A bottle of whisky from the ship’s medical comforts served as payment.

One morning, plodding our way down Channel, slowly but surely, we picked up the Sovereign Lightship, through the mist, fine on the bow. Passing within hailing distance, we noticed an old fellow on the lightship with binoculars raised, gazing at us. As we passed he bellowed in a stentorian voice: ”Where yu’ bar’nd?” Upon being informed – Sydney, N.S.W. – he roared back through his cupped hands: “Bar gum, yu’ got a’ell o’ a long way t’ go.”

We continued to battle our way southward, and one night at about 6 p.m., rounded Ushant. Night was coming on fast, with a dirty looking sky to the nor west, and an ugly sea rising, but we set our course across the Bay of Biscay, and before midnight were wallowing and lurching in proper traditional weather of the Bay, running before a howling gale.

She became a gigantic surfboard

It was fortunate she was steering well, but the old “K” had one saving grace. When running before a heavy sea, if she began writing her helmsman’s name in her wake – even going back to dot the i’s – when put in hand gear, she usually steered like a yacht. Then word came from the engine room that she must be stopped for repairs. The old man stood by the wheelhouse directing the helmsman, as great seas were striking the square stern, transforming the vessel into a gigantic surfboard. Thus we covered two-and-half miles by patent log, during the half hour we were stopped, a speed of five knots. Rounding Cape St. Vincent it became only too apparent that the vessel was settling by the head. Bilges were sounded, but there was no sign of water, and though there were many compartments, there were no means of sounding these.

One fine morning the “K” steamed through the Straits and up to Gibraltar. The pilot came off and after the usual questions said “You are a proper mystery ship, I thought when I saw you in the distance, that you were coming in stern first.” “So we are!” replied the captain, quite seriously. To the pilot’s stare he explained that by the way our engines and boilers were placed, we were actually steaming stern first.

When we came to anchor a passing boat drew our attention to the fact that there were four holes in our bow. The small hatch of the compartment which served as the chain locker was at once removed, and it was found to be full of water, with four round points of daylight showing at the bow. The settling by the head at sea was now explained. Two locking plates which had been fixed, one each side of the for’rd rudder (which was of course not in use) had come adrift in the heavy weather, leaving four holes, about an inch in diameter, to allow a slow but steady inflow of water into what we shall graciously call the forepeak, as her bows dipped. An hour or so later when alongside, we bailed and pumped out the water, and shore engineers were soon at work refixing the locking plates.

Through the Suez Canal

After coaling, taking in stores, and squaring up, we sailed in the evening for Port Said, and what a treat it was to get some fresh stores. The “bully beef,” salt horse and ship’s biscuits we had been having were reminiscent to some of us of our early days in sail, and it was no hardship to change such a diet for one of fresh meat, vegetables and fruit.

We duly arrived at Port Said, and having taken coal on board, and shipped the searchlight for negotiating the canal at night, we set forth, with hopes of a yachting trip through this sheltered stretch of water. However, we had not been many hours in the canal, when the pilot was ordered to anchor. Once the signal was given, the mate let go, and the pilot, completely forgetting that we had a propeller working at the bow as well as the stern, gave her a touch astern. The result was that we immediately had a neat half turn of cable round the for’rd propeller, and all hands were out at mooring stations for four hours, heaving and slacking, whilst the cable was cleared with the assistance of native divers.

The pilot instructed us to signal the next signal station we passed that we could not anchor in the Canal owing to the offending propeller at the bow. We were granted the right of way, like any mailboat. The old “K” seemed to know it, for she scampered through the smooth water.

Clearing Suez, she behaved nonetheless skittishly coming down the Red Sea, until the heat became so intense, that she nearly killed one of the firemen. The watches had to be kept, so a sailor was loaned to the engine-room staff. This made us hopelessly shorthanded, working coal on deck, so a brief stop at Aden was made to pick up a native fireman. Once we got to sea again, this poor fellow looked hopelessly out of place. He could speak very little English, but he did his work well, and left us in Singapore, with more money, probably than he had ever dreamed of, and his passage back to Aden.

Ploughing towards Singapore

Leaving Aden, the old ship wallowed, ducked and dived, and endeavoured to throw us off our feet, in the strong, south-westerly monsoon which we encountered. Day followed day, working coal in a sticky, humid heat, rolling and tossing across that 2,500 miles of ocean, till we raised Colombo late one afternoon. As we approached the moles, there was a heavy sea running, and the pilot could not board, but he directed our skipper from his boat, and he, by obeying and using his own judgment, soon had us fast to the buoys. By nightfall the day following we were once again ploughing our way through the Indian Ocean; this time towards Singapore.

Life went on with a certain damp regularity until we entered the Straits of Malacca and then to Singapore, with what we hoped was the worst part of our voyage behind us. There all hands had a night ashore, with cash advanced. The next day the old man went ashore, leaving instructions to paint the funnel. Now we had the paint, it was true, but no means of hanging men on the funnel to paint it. After concentrated thought on the mate’s part, two short ladders were lashed together to reach the top, then a man was sent aloft to hang two boat gripes with small iron blocks attached, over the funnel rim. By reeving the ropes off the boat’s sea anchors through these blocks and manufacturing a couple of bosun’s chairs, we had painting-gear equal to that of a first class mail-steamer. Thus when the head of our little community returned, our funnel shone like a housewife’s newly-polished saucepan.

Dipping our ensign to the British men-o’-war in port, we steamed out of Singapore, on what was roughly the second half of our journey. The weather was kinder to us until we reached the Arafura Sea, where we ran into strong south-easterlies. These may have been no more than strong trades, but to us, a howling gale. Water pouring over the rail threatened our coal, by taking the breakwaters and their contents overboard. The loss – at this stage – would have been little short of a disaster, and consequently the vessel’s speed was yet again eased right down. In spite of this, as we of the watch below were turning in at midnight, we seemed suddenly to lose our buoyancy for’rd, and the bow seemed to be settling down under our feet. We dashed for the scuttle, and suddenly right overhead there was a terrific crash. The door was jammed, with gallons of coal black water pouring through the cracks, and before long the messroom floor was a foot deep. We were trapped; but when our banging on the scuttle door ceased for a moment, we heard the scrape of shovels, and a minute or so later, the door was thrown open. There stood the port watch in dripping oilskins, shovels in their hands, and surrounded by a heap of coal. There we stood in – well, we won’t go into that.

Pile-driving to Thursday Island

Our fears had been realised. Our craft had put her head under, shifted a goodly portion of coal on the foredeck, and filled up her decks with water, which was what had given us that “sinking feeling”. Luckily, we had not lost much coal, the sea shifting the bulk of it over our scuttle. There was work till daylight, the watch on deck repairing and moving coal back once more between the breakwaters, the watch below bailing out the quarters, and ducking to the engine room with bundles of bedding and clothes to be dried out. By noon that day all was fairly shipshape.

Our vessel, “pile-driving” badly, made the teeth of everyone on board chatter. Consequently, one dark overcast night, approaching Thursday Island, it was discovered that the glass of the standard compass was broken and the card off the pin. We were in fairly shallow water, so anchored until daylight, to effect repairs to, and to check the deviations of the compass.

Eventually reaching Thursday Island, the old man decided to navigate the waters of the Torres Straits without a pilot. One morning, when we were passing Turtle Island, the man at the wheel announced that she would not answer the helm, already being two points off course. No sooner had he said this, than she began to vibrate and bump, as if ashore. When the ship was stopped, soundings were taken, and showed plenty of water, but a glance over the bow soon solved the mystery: The for’rd rudder was right across the bow! The locking plates had come adrift again, but, in addition, the locking pin – which went through the deck, had jumped up a few inches, leaving the rudder free to swing across the bow. After anchoring, and spending four hours or more securing the unruly rudder, we proceeded to Cairns for yet more coal. After bunkering there, we continued to thump our way south.

Late one afternoon we were abeam of Lady Elliot Island, “heaving up and down in the same hole,” as the saying goes. Thinking to save fuel, the old man decided to anchor in the lee of the island, bringing her up into smooth shallow water, just at dusk. No sooner was the anchor down, than a message winked out from the lighthouse morse-lamp on the island “W-H-AT S-H-I-P?” It was some time before the lighthouse keeper could make out our name, but there was some excuse for him, as “KOONDOOLOO” is really a mouthful, or rather eyeful, when spelt out in morse code. Eventually it was received, and the flashed conversation continued:

Lighthouse: “What are you?”

Ship: “Sydney Harbour ferry.”

Lighthouse: “How the devil did you get out here?”

This last question we decided to ignore.

The next day was a splendid opportunity to replenish the bunkers from our stock of coal on deck. It was a treat to wheel a barrow along the deck without the feeling of being on a switchback railway. Our bunker being full once again, we resumed the long voyage. By the time we had reached Cape Moreton, such a sea was running that once again we could make no headway. As that precious commodity, coal, was again running short, there was nothing for it but to pay a coal and courtesy call to Brisbane. In smooth water we went charging up the river at a speed of a shade under 14 knots, passing everything in the channel.

Last leg to Sydney

By four o’clock in the afternoon we were securely tied up at the coaling berth, and by five o’clock beards were being removed, shoes polished, and musty shore-going suits aired. Money was exceedingly scarce, but by dint of borrowing, and making rash promises of double payment, a financial system evolved which would have made a financier turn green with envy. The next day all hands were busy coaling while shore engineers again made fast the for’rd rudder. We learnt then that we were to have a passenger to Sydney. This was received by most of us with the proverbial grain of salt, till late in the afternoon, when our passenger’s bags had arrived. He turned out to be a reporter from one of the Sydney papers, signing on as a purser.

On the last lap rounding Cape Moreton, we were again battling against the elements. Our passenger was marooned on the bridge, the officer off watch having to send his sea boots up for the reporter to come down to meals as decks were constantly awash. During the next 24 hours we thumped into a big sea, but in the first dogwatch the wind hauled aft, and knocked the sea down.

The old ship made good progress, and at 2 am the loom of the furnaces at Newcastle were abeam to starboard. On the morning of July 22 we were feeling our way up to Sydney Heads in misty rain, exactly 84 days since casting off in Leith: only 84 days, yet we seemed to have lived a lifetime, since that well-remembered day.

The furnaces of Newcastle

Picking up North Head, then sighting the “Captain Cook,” we soon had the pilot on board, and were steaming to our berth at Milson’s Point. As different ferries sighted us, they set up a screeching with their whistles, and to this fanfare the “Koondooloo” was played to her berth by the ship’s piper, taking up a position among her smaller sister ferries, which after all was her proper place in the scheme of things, for our vessel’s adventurous voyaging was over, forever.

An excellent account of the Koondooloo’s career can be read on Bill Bottomley’s website, here:

Wonderfu l story and told by an old salty.