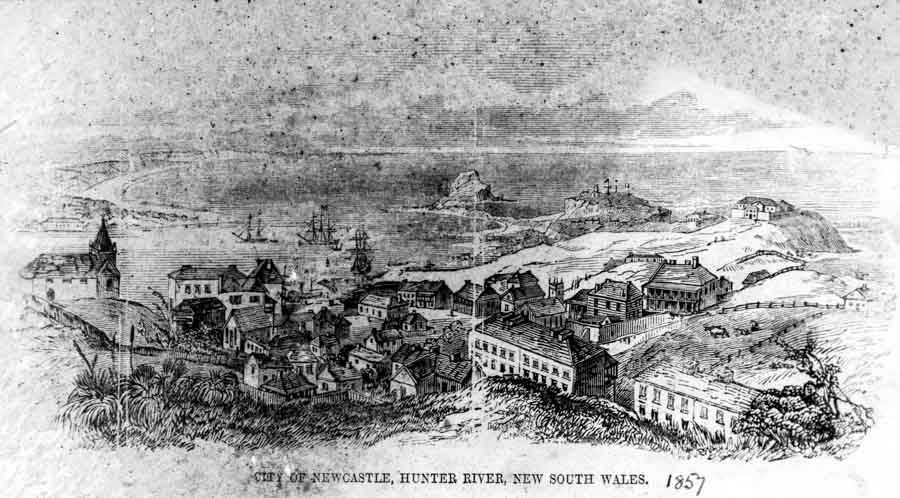

WHEN the newly formed NSW Railway Commission proposed in 1856 to extend the Newcastle railway line from Honeysuckle Point to the city’s east, many of the town’s inhabitants were horrified. An angry public meeting was held and nearly a third of the town’s population signed a petition begging the government to put a stop to what they saw as a destructive plan.

Newcastle was designed and laid out around its harbour and to have access to this tremendous feature wiped out by a fenced-in railway line was considered an outrageous imposition. Leading Newcastle citizens including James and Alexander Brown, MP Alexander Scott and Dr William Brookes gave strongly worded evidence to a select committee set up by the government to consider the issue.

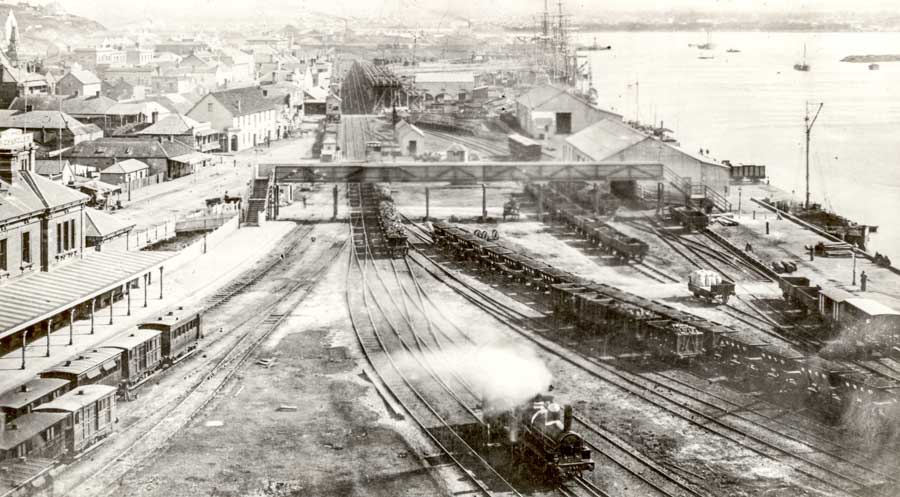

.

But strong as public feeling was against the plan, it was no match for commercial interests. Against the citizens’ petition of 403 signatures calling for the terminus to be left at Honeysuckle Point was a counter-petition of 12 signatures from Newcastle’s fledgling chamber of commerce demanding the extension to Watt Street. Some of the city’s most influential businesspeople, as well as some east end property owners, sensed in the rail extension plan an opportunity for profits and they threw their weight behind the determination of the railway commissioner to extend the line in the face of public protest.

Battle for freight trade

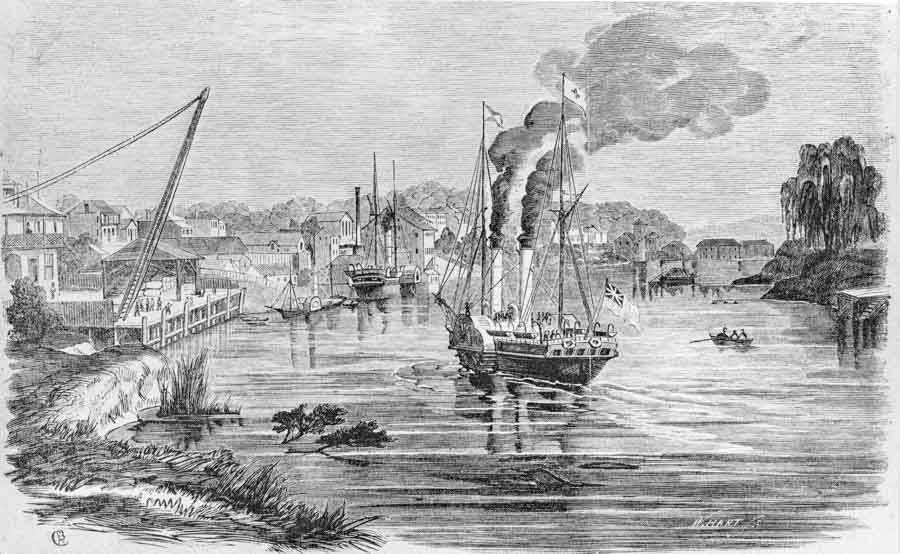

The argument boiled down to a battle for the freight trade between the immensely productive Hunter Valley and the state capital of Sydney. Up until this time, the trade was carried out more or less directly between the river port of Morpeth and Sydney, with Newcastle of no real importance for anything other than coal. A railway line from Maitland to Newcastle offered the prospect of cutting out the Morpeth river steamers and winning the freight trade for ships operating out of Newcastle. For the plan to work, the businessmen and railway commissioner believed, the rail had to terminate near a deepwater wharf at Newcastle. At Honeysuckle the harbour was considered too shallow.

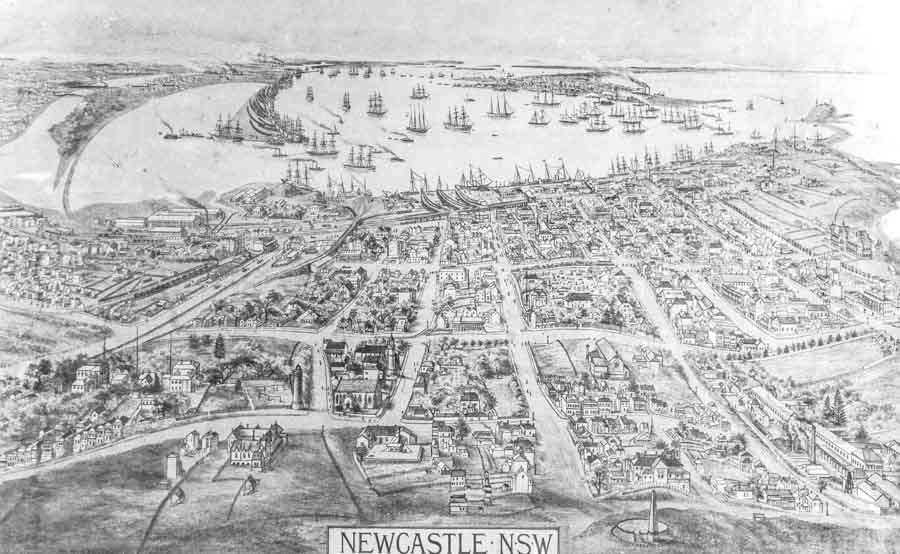

Most people agreed that Bullock Island (Carrington) was the ideal site for a freight and coal terminal, but it needed a lot of reclamation work and that would take years. The quick, cheap and arguably nasty option was to sacrifice Newcastle’s harbour frontage by cutting it off with a rail line to deep water opposite Watt Street.

At the time of Newcastle’s first furious rail debate, the government had only recently taken over the still incomplete rail line. The project had been begun a few years earlier by a group of mainly Sydney investors who had seen the potential to profit by taking over the trade in produce from the booming Hunter Valley by rail via Newcastle.

.

Maitland was the administrative and commercial centre of the Hunter Valley and it had its own port on the river at Morpeth. The river was a great natural highway, but intensive farming was leading to the channel being silted, wash from the steamers themselves compounded the erosion of the river banks and soon the colonial administrators were forking out money to keep the channel clear for trade. The railway investors reasoned that, once they got their rail line built, produce could be carted to waiting ships at Newcastle and the public purse wouldn’t have to subsidise the steamship companies any more.

While the idea might have been a good one, the enterprise ran into trouble. The engineering challenges were tougher than they seemed. Labour was expensive and hard to keep. The economy took a nosedive. Land at Honeysuckle Point,where the first Newcastle rail terminus was built, got caught up in a bitter and messy compensation argument with the Anglican Church and its tenants.

Question mark over Honeysuckle

After tens of thousands of pounds had been spent trying to complete the line, the colonial government stepped in. A Railways Commission was established to take over the Hunter line and a similar private venture between Sydney and Parramatta. Again, the government was mostly motivated by the prospect not only of freeing itself from the expense of keeping the river channel clear for the private steamboat interests, but also of earning regular revenue by carrying freight on its own trains.

There had always been a question mark over the site of the Newcastle terminus at Honeysuckle Point. Tortuous negotiations over the church land (which had years before been set aside for a school) made it an expensive option. .At the time of the government takeover Of the railway, the priority was to finish the project as quickly and cheaply as possible, while producing the best result for freight shippers. The government wanted a return on its money.

.

Many residents of Newcastle were horrified at the thought of a railway cutting their north-south-running streets at the harbour edge. The settlement’s relationship to its harbour was possibly the single most important and appealing aspect of its design. Fearing that the railway commissioners and the business interests would ride roughshod over their concerns, a public meeting of residents rushed a petition to the Legislative Assembly in Sydney. The petition, signed by 403 Novocastrians – at a time when the total population of Newcastle was only about 1500 – begged the government to make the railway commissioners reconsider.

The “petitioners, aware of the contemplated extension of the Hunter River Railway from its present Terminus at Honeysuckle Point, to a site at the eastern extremity of the city” were concerned that “the said line of Railway, according to the reported plan of the commissioners, will, besides intersecting all the streets at right angles with the wharfs, traverse the margin of the harbour from west to east, and consequently through a reserved portion of the wharf known as Market Wharf, and to which is annexed a reserved road to the Market Place, and all of which . . . have for a space of 22 years been set apart, proclaimed and dedicated to public use as a market and a market wharf. Your petitioners, deeply convinced of the inutility of the proposed scheme as a necessary or desirable project, submit … that before so much public money be permitted to be sunk in this extension and a terminus at the Sand Hills, that railway facilities be afforded to the up-country districts.”

The petitioners begged the government to “afford its protection against this encroachment on the city and its privileges”. They were wasting their breath.

Citizens versus coal and business

The Chamber of Commerce had sent its own petition, signed by 12 people. The chamber had heard “with surprise, that some persons entertain the erroneous opinion that the extension of the railway along the line of wharfs at Newcastle, which is the measure that the convenience of trade most requires, would injuriously interfere with the traffic of the city”. The chamber begged the government to “cause the extension of the Hunter River line of railway to a terminus communicating with deep water at the east end of Newcastle”. A government-appointed select committee took evidence from a number of people, including leading Novocastrians, and asked many sharp questions about the impact of the railway on the city. Some of the evidence makes fascinating reading more than 150 years later.

Having taken over the Maitland-to-Newcastle rail project, the NSW Government wanted to ensure it wouldn’t become a costly white elephant. It trusted its chief commissioner of railways, Gother Kerr Mann, to make its new rail asset profitable as quickly as possible. In 1856, after about a year in the job, Mann was convinced that the quickest and best way to make the project pay was to extend the line from its existing terminus at Honeysuckle Point to Watt Street. At that time the area east of Watt Street was known as The Sand Hills, for obvious reasons. Most Novocastrians lived in the area between Watt and Brown streets, and many found the idea of a railway to The Sand Hills offensive.

Mann was questioned by the select committee: “If the proposed line along the edge of the harbour to Watt Street is finally fixed upon, will not that line very much interfere with the convenience of the inhabitants of Newcastle by intersecting the various streets, which I believe all run from north to south?” he was asked.

“I do not believe it will,” he replied.

And again: “Do you think after a town has been laid out by the government as this has, with water frontage … that it is any breach of faith with the parties who have bought land in the streets leading to the water to construct a railway which intercepts access to it?”

“Quite the contrary,” he answered.

The AA Company states its view

Firmly on Mann’s side was an influential former senior employee of the powerful Australian Agricultural Company, William Croasdill, who was shortly to leave the colony and return to England. Croasdill saw no problem with the streets of Newcastle being intersected by a railway line and fences.

“On the whole consideration of the subject I am disposed to believe that it is so much a shipping place and that it will be as well accessible, even though the railway is laid down there. A locomotive going down there would be less objectionable than the numerous horses with their wagons on the trains which they have now to bring down the coal on,” he said. “One or two points of access” would be enough for the residents.

“It is to be presumed that the value of land at Newcastle near the harbour is founded on the belief that it will be shut out from a sight of the water by the masts of ships and by railways too; that Newcastle is not to be a pleasure port at which to run down bathing machines but a dirty place of trade, in coals in particular. When that is a coal shooting and shipping place there will be no comfort in the question. It will be all for business, and as much a helter skelter place of trade as the Circular Wharf in Sydney,” Croasdill observed.

.

Not everybody sided with the railway commissioner, and some of the opposing opinion was strong.

Edward Orpen Moriarty, the government engineer in charge of Hunter River port improvements, was asked: “What is your opinion with respect to the question whether that line would not interfere with all the streets through which it has to pass to reach the edge of the harbour, from south to north?”

“It would cut off the water frontage from the town,” Moriarty answered. “If I were doing it I should have my main terminus at Honeysuckle Point or at some other place likely to be central to the town, with a branch to the water side.”

Bullock Island is the future

Moriarty found it “objectionable” to cut off the whole water frontage of a town and he knew of no instance where this had been done. “I do not think it is necessary for the main terminus of the railway to come down to Watt Street,” he said.

Hunter Region MP Alexander Walker Scott, (also a trustee for the troublesome church land), preferred Honeysuckle Point as a terminus because it was “closer to Bullock Island which one day must be the important freight terminus”. Scott was asked: “Do you know whether the extension of the line will interfere with private property?”

“I should say distinctly it would interfere with the rights and privileges of the people of Newcastle in an egregious manner. There must be a double fence and gates and people could only be allowed to approach the water when the carriages were not at work,” he replied.

.

Noted ship owner Alexander Brown stated that the line extension “will be the cause of great public inconvenience”, intersecting “seven or eight streets”.

Alexander’s brother James believed the proposed extension “would not only be no benefit, but it would be taking the terminus away to the end of the town”. “Honeysuckle Point will be the centre of the town. In fact it is almost the centre now,” he said.

Perhaps the most powerful advocate for extending the line was the railway commissioners’ new chief engineer, John Whitton, who had been in the colony just six weeks. Whitton had a low opinion of Newcastle which had struck him as “an exceedingly small place” and “a very poor place”. He didn’t believe the proposed line would intersect many streets. It would actually pass along their ends on undeveloped land. The frontage to the harbour was not really open for any practical use, with pools of water and embankments of ballast forming obstacles. As far as Whitton was concerned, leaving the terminus at Honeysuckle Point would have condemned the line to a profitless future.

Newcastle “a very poor place”

“The terminus being on the wharf is the only thing that will make the Newcastle traffic pay and if it be not there I do not think it would be worthwhile to work the trains to Newcastle at all. The only traffic of any consequence that you could expect from Newcastle would be that brought by the steamboats from Sydney; and if the railway is to have a chance of success, you must endeavour to make some arrangement by which the traffic of the steamers will be secured to the railway,” he stated.

In Whitton’s opinion, the whole project had been a mistake. The position could be salvaged, but only by extending the line. “I think the only thing that can ever repay the government for making the line from Newcastle is to give them every opportunity of getting the traffic from the steamers and to prevent the steamers running in opposition to Morpeth,” he said.

Whitton had grave doubts about the future of Newcastle if the extension was not allowed: “I think the only way you can ever make anything of Newcastle is by making the railway terminus there. There is no trade there now except the coal trade. I do not see the slightest possible injury the town can receive from it,” he said.

.

DESPITE the threat to the government that its railway would not pay unless the line was allowed to cut off Newcastle from its harbour, one member of the select committee remained highly unimpressed. Committee member Elias Carpenter Weekes proposed the following motion:

“The evidence of the various witnesses-examined does not justify the adoption of so unusual a proceeding as running a railroad on street level through the town of Newcastle to Watt Street, more especially when it is proposed that such railroad should be fenced in with a close fence thus shutting out the inhabitants from all access to the water frontage”. His motion lost, three votes to one.

The committee resolved that it couldn’t justify an early, expensive plan for separate street-level goods and passenger lines plus an elevated coal line. Instead, it resolved “That a single line of railway for goods and passengers from Honeysuckle Point to the wharf at Watt Street should be laid down in the most economical manner consistent with strength and efficiency and that the railway buildings necessary at the terminus at Watt Street should be of the most inexpensive construction.”

As it was “doubtful where the main terminus at Newcastle will be ultimately fixed”, the committee recommended against buying more of the controversial and expensive Anglican Church land at Honeysuckle Point “than is strictly required for railway purposes”.

The interests of commerce and its government advocates had collided with those of the residents of Newcastle and won a comprehensive victory.

.