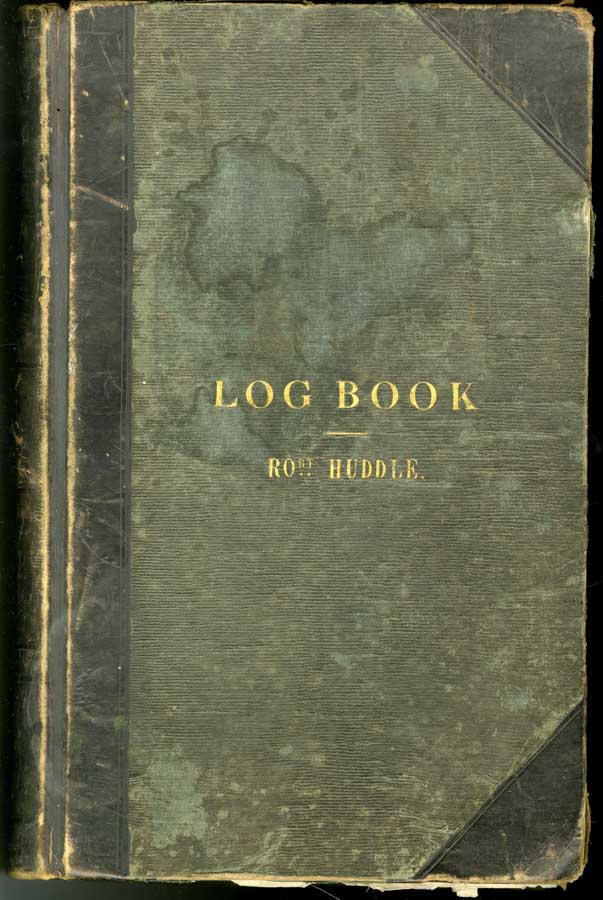

A year or two ago I was privileged to receive a remarkable book from the library of a friend who had passed away. It is a hefty bound volume, containing a logbook of the travels of a 19th century English seafarer named Robert Huddle. The book contains an introductory essay, day-by-day accounts of many of his voyages and experiences, and a concluding essay. The book is handwritten in ink, and its pages are interspersed with delightful watercolour paintings depicting some of the ships on which Mr Huddle worked and scenes he observed during his travels.

I know little about Robert Huddle, other than what I can gather from his book. He began his seafaring life as a boy in 1856 and spent 10 years in sailing vessels before making the move to steam in 1866. By his own account his favourite ships were those of the Cunard Line – particularly the splendid Scotia – and he also spent a season as part of the small crew of the luxury yacht Hebe in the Mediterranean, on which an invalid member of the MacIver family (part-owners of the Cunard Line) was wintering.

He travelled to the Far East and – after some difficult experiences including two shipwrecks – got good jobs with the harbour authority of the British Straits Settlements at Singapore and Penang. A nasty accident aboard a burning ship damaged his health severely, and he returned to England in 1892 to retire on a pension, not yet aged 55.

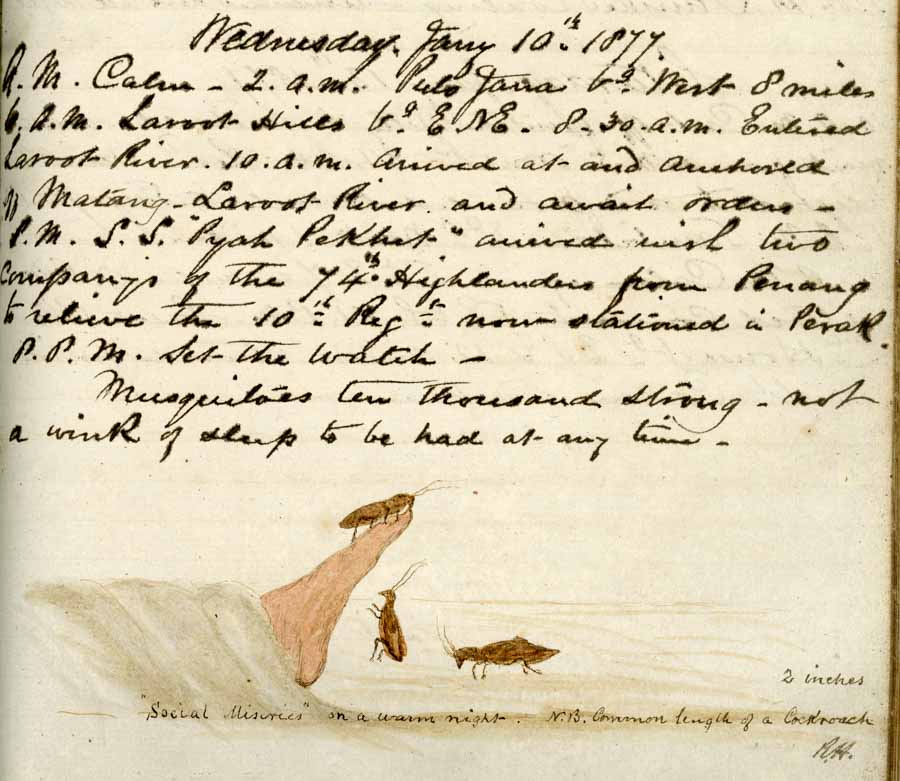

Robert Huddle’s logbook is an odd volume. Its oddities probably reflect life at sea; long periods of relatively dull observations of weather and wind are punctuated by sudden accounts of exciting incidents. Now and then the author lets slip some personal musings that give a little sense of his character and yearnings. Here and there small sections have been sliced out. Perhaps this represents some censorship in his later years ashore.

The logbook is a daunting read for those who aren’t used to reading old-fashioned longhand, and the difficulty is increased by the constant use of terms unique to the sea and to the times in which the author lived.

What follows in this post is a full transcript of Robert Huddle’s opening essay to his logbook, punctuated by some of his watercolours. I plan to produce at least a couple more posts from the book, as time and inclination permit.

Introduction to his logbook, by Captain Robert Huddle

Contained in this log book are some memorandums briefly indicating when, where and how the greater part of my life has been occupied. A similar book to this I’ve previously written showing my travels during the elapsed time between September 1856 and December 1864. Those notes are lost and are cause of great regret, precluding me from embodying here items of those voyages more fully. However there is not much good in lamenting over lost material. It saves me in this instance the necessity of detail though I am able to record accurately the dates of departure and arrival, to use a convenient phrase. These have been got at correctly for the purpose of this epitome.

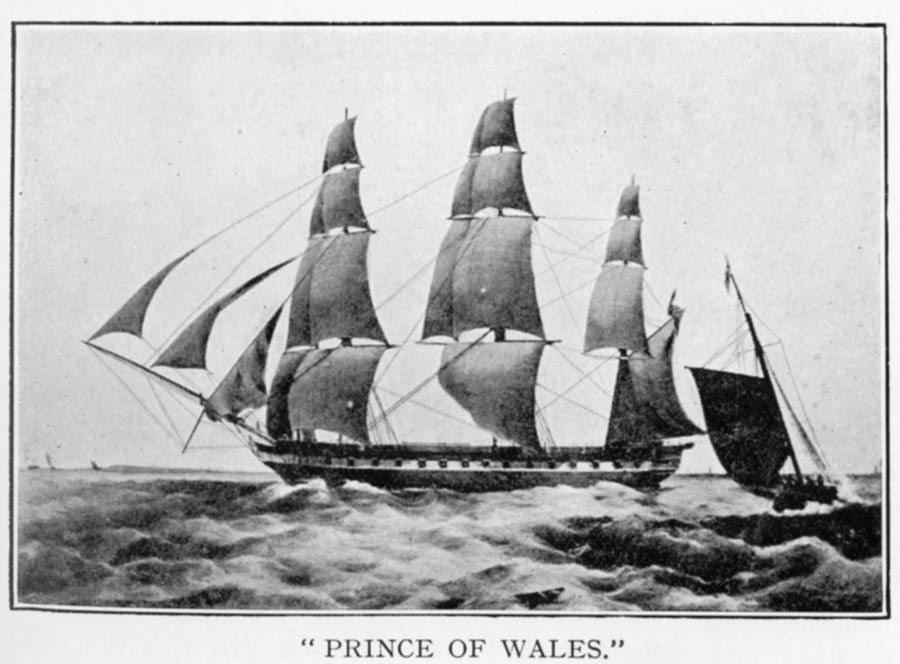

To precede the first entry in this book some outline of my travels deserve mention here as an appendix. My first entry on board ship was on the 10th of September 1856 as a boy in the well-known ship Prince of Wales of Blackwall owned by Messrs. Green, whose status in the shipping world then and years preceding and later was second to none in Great Britain. Their ships were officered by gentlemen. The crews were men who mostly had served in their employ all their sea service, each of whom manifested as much interest in the ship as if it were his own.

I left London in the Prince of Wales on the 10th of September 1856 bound for Calcutta having on board a large number of saloon passengers and also several high class horses. After long passage arrived in Calcutta early in January 1857 – returned with time-expired soldiers reaching London via Saint Helena in July 1857. Sailed again in same ship on 19th of September 1857 from London bound to Calcutta arriving in that port on the 3rd of January 1858. Sailed again from Calcutta on the 15th of March 1858 having on board invalid soldiers fresh from the mutiny. Called at Saint Helena on the 29th of May where I spent half a day on shore and arrived at Gravesend on the 10th of July 1858. Left London again in the Prince of Wales on the 4th of January 1859 bound to Melbourne full of passengers – first second and third class. Arrived in Melbourne on the 28th of March, a run of 82 days. Left Melbourne on the 30th of April 1859 with a cargo of wool and having a large amount of gold on board. Reached London via Cape Horn on the 3rd of August – 94 days passage. Sailed again in the Prince of Wales from London on the 20th of November 1859 bound for Melbourne, arriving there on the 3rd of February 1860 after a splendid run of 75 days from the Downs.

Sailed from Melbourne on 30th of April 1860 with a large quantity of gold on board as also wool, arriving in London via Cape Horn on the 17th of July – 78 days from Melbourne. This was considered remarkably good sailing.

This favourite ship prior to her sailing from Melbourne was advertised in the Australian papers as follows extract: “The Blackwall frigate ship Prince of Wales is acknowledged by competent judges to be one of the finest merchantman ever launched and for strength of build and beauty of mould is unsurpassed even by the first class frigates of the Royal Navy to which she bears a close resemblance.” During my four voyages in the ship I was taught by her officers much rudimentary knowledge of navigation in seamanship and when I quitted her for good felt I had then passed the embryonic stage of the profession and capable of tracking out a new path to advancement in it. In this endeavour I received through the interest of Messrs. Green a berth as third officer in the ship Alfred of Liverpool – Captain Billinge – then in the Shadwell basin. This was late in August 1860.

I voyaged to Cardiff in the Alfred with ballast after taking on board 1760 tonnes of coal. Left Cardiff on the 15th September 1860, bound to Bahia, arriving there on the 23rd October. After detention of 64 days in Bahia – our crew discharging cargo – sailed in ballast on the 26 December 1860 bound for Mobile and arrived there on the 5th of February 1861 after a pleasant journey of continued fine weather and smooth water. Took on board here an entire cargo of cotton and sailed from Mobile on the 9th of April 1861, bound for Liverpool – which port we reached on the 5th of May having had a rough passage across the Atlantic. After this cargo of cotton was discharged sailed again in the Alfred on the 25th of May from Liverpool bound to Québec in ballast . Arrived in Québec on the 25th of June 1861. During this voyage across we had an uncommon experience, being for several days when in the locality of the Newfoundland Banks completely surrounded by innumerable icebergs – some of them attaining a height from 250 to 300 feet and much greater length. The Alfred luckily had just sufficient steerage way to avoid contact with these, there being but little wind and comparatively smooth water the whole journey with about 21 hours of daylight each day. Took on board a cargo of timber, also a deck load, and sailed from Québec on the 1st of August 1861, bound to Liverpool, reaching there on the 20th of August, having had a fresh westerly gale behind us the whole way across. I then returned to the home of my parents for holiday. On the 6th of October 1861 sailed again with Captain Billinge in the ship Anglo Saxon with a cargo of salt bound for Calcutta. Arrived there on the 12th of February 1862 and had a long weary passage. Took on board here an entire cargo of gunny bags and sailed from Calcutta on the 6th of May bound to Havana. Arrived there on 4th September 1862. In this port I had the misfortune to contract yellow fever and was in hospital during the ship’s delay in Havana. Sailed from Havana in ballast on the 29th of September bound to New York. During this passage the Anglo Saxon was brought to by an American war vessel for search purposes when off Cape Hatteras. Arrived in New York on the 20th of October – my 21st birthday. Took on board here a cargo of grain in bulk and arrived in Liverpool early in January 1863.

When I finally severed my services – as also did Captain Billinge – from these owners, I then returned to London with the intention of obtaining a board of trade certificate as second mate. During my time of service under Captain Billinge in the Alfred and Anglo Saxon the period was one of hard practical work. The employment of these ships was so distinctly different to that of Messrs Green’s: a different style and tone prevailed in them less favourable by comparison. Captain Billinge was the only attraction which tempted me to remain in them so long as I did. I acquired some considerable experience in these vessels and felt pretty certain when I left them I had little else to learn other than that experience which is inseparable from youth to much riper years. In the Alfred and Anglo Saxon hard work was the predominant regimen from beginning to end. There were no more cats then could catch mice. Captain Billinge was a thorough seaman and the time I refer to I looked up to him as an ideal ship master. Now many years later on in life after a lengthy experience and association with ship masters both afloat and onshore, I still hold to the opinion I did when serving under him. He, after leaving the Anglo Saxon, was appointed chief officer of the Great Eastern and later on was in command of the London and New York steam ships, the Cunard mail steamers and in the Ocean Steam Ship company’s vessels to China. On several occasions during my residence in Singapore I had the agreeable pleasure of meeting him.

In the Owen Glendower to New Zealand

I obtained my second mate’s certificate in April 1863 and was then eligible for a berth as such and eager for employment. Shortly after this I obtained an appointment as second officer in the Blackwall ship Owen Glendower and on the 27th of May 1863 sailed in her from Gravesend bound to Auckland, New Zealand, full of passengers of all sorts and conditions. This old ship was as it were one of the “had beens” and then trading on the prestige of her past good reputation, but in reality she was rather a trap insofar that she leaked like a sieve. When under canvas her pumps were in constant requisition and use. We had got no farther on our voyage than the Eddystone Lighthouse when the crew en masse absolutely refused to pump or proceed on the voyage, so we were compelled to put back to our nearest port – Plymouth. Here a survey was held on her which ended in the Owen Glendower being examined afloat and having a new set of pumps provided. This being done we then sailed from Plymouth on the 12th of June 1863 and arrived in New Zealand on the 29th of September after a somewhat eventful and trying voyage, for as we approached the southern latitudes pumping became the order of the hour – passengers taking their turn at the pumps to relieve the crew. Our voyage, anxious as it was the time, was made to pass agreeable as far as was possible, bar the always-present anxiety about how much water the ship was making. Happily by dint of hard pumping this was always kept below the danger limit. Our passengers in the saloon – amongst them was Sir Charles Wentworth Burdett, Bart. – were the pink of good fellows with an admixture of ladies both married and single. Some of the latter engaged to be married on arrival in New Zealand. These added a charm to the many amusements in evidence at all times when the weather permitted. Charades, concerts, auctions of old clothes, birthdays real and assumed, celebrations etc etc were amongst the items on the program throughout the passage. We had a delightful stay in Auckland enlivened somewhat by the wedding of the captain of the Owen Glendower, W.H. Norris – a worthy and capable officer. He married one of our lady passengers.

Owen Glendower sailed from Auckland New Zealand in ballast on the 19th of December 1863, bound to Bombay, passing through the Bass Straits en voyage, sighting the coast of Australia and Tasmania at times. We reached Bombay on the 22nd of March 1864. This passage with only four saloon passengers on board was in comparison to the outward one very monotonous. There wasn’t a cause for anxiety about pumping. The ship being in ballast, her leak was above the watermark. After taking on board a cargo of cotton we sailed from Bombay on the 2nd of July 1864, bound to Liverpool. After being at sea one day and having nasty weather, the Owen Glendower started leaking considerably and the crew again refused to proceed. We at once put back to Bombay when a survey was held and the ship pronounced unseaworthy. Her cargo was discharged, crew paid off excepting the 1st and 2nd officers and a few midshipmen who were retained on board. During this detention I passed my examination in Bombay for first mate and in December was paid off from the Owen Glendower. I afterwards learnt that this ship foundered at sea with the loss of all hands somewhere between Bombay and Mauritius.

The preceding references relate to occurrences previous to the birth of this volume. What followed on henceforward I shall shortly reiterate here.

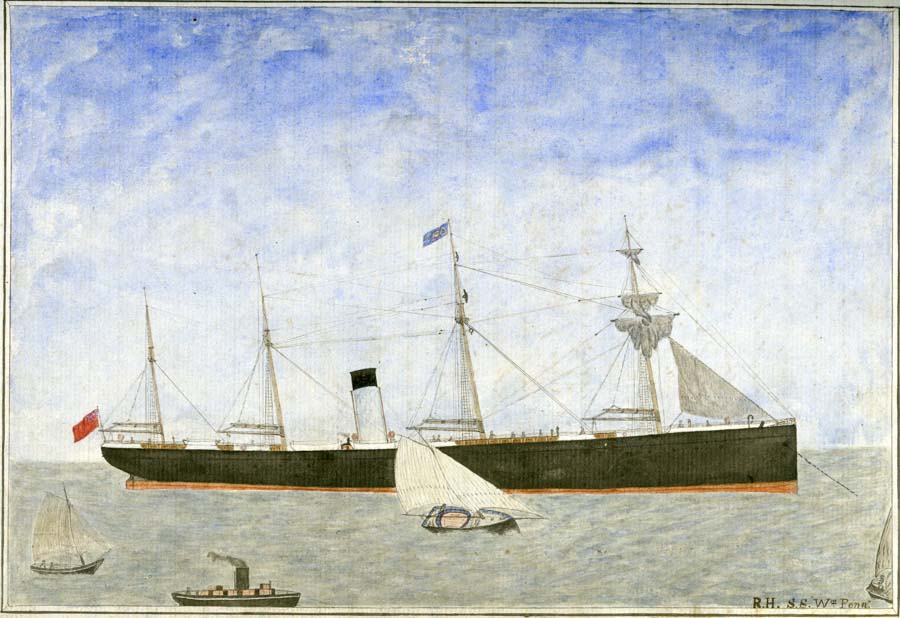

In the Magdalen commanded by my shipmate and late chief officer of the Owen Glendower – W.B. Minhinnick – I was content as a sandboy. The details of my travels in her are already recorded herein. I simply note here that in the Magdalen all on board of her felt pangs of hunger and were hard pressed for something to eat during my voyages in her. It was in this vessel my services in sailing ships terminated and I bid her a final adieu in Liverpool, March 1866. This craft was a notorious slow sailer. On no occasion during my time in her – no matter how fresh the wind or great the spread of canvas – she never exceeded of more than 8 knots per hour. After being paid off from her I returned to London, worked up for my Master’s examination and obtained my master certificate number 27524 on the 12th of May 1866 after which – to use an Americanism – I had a real good time on shore till I had the good luck to join my old friend Captain Billinge in the London and New York steamship William Penn. This was in September 1866. I continued with this company in the SS William Penn and SS Belona in the Atlantic trade till the end of 1869 and the period was one of perpetual hurry up. Sleep was an unknown quantity. My surroundings were so transformed from anything like I had previously experienced that it appeared to me everything was expected to be done, and indeed was done, at high pressure speed, when in port at any rate. Of course when at sea the routine duties are much alike in all ships. Where large numbers of passengers are carried an officer has more rest. On one of the voyages in the steamship William Penn her machinery broke down – 3rd of September 1867 – when we were 3 days out from New York. On this journey we had amongst our passengers a large number of refugee soldiers fresh from the Mexican campaign under the Emperor Maximilian. These chaps were a motley lot representative of every nationality in Europe, bar English, most of them from the Levant and Mediterranean ports. We put back to New York and during the ships detention there waiting for a new shaft I took the opportunity of spending a few days’ holiday at Niagara Falls and city.

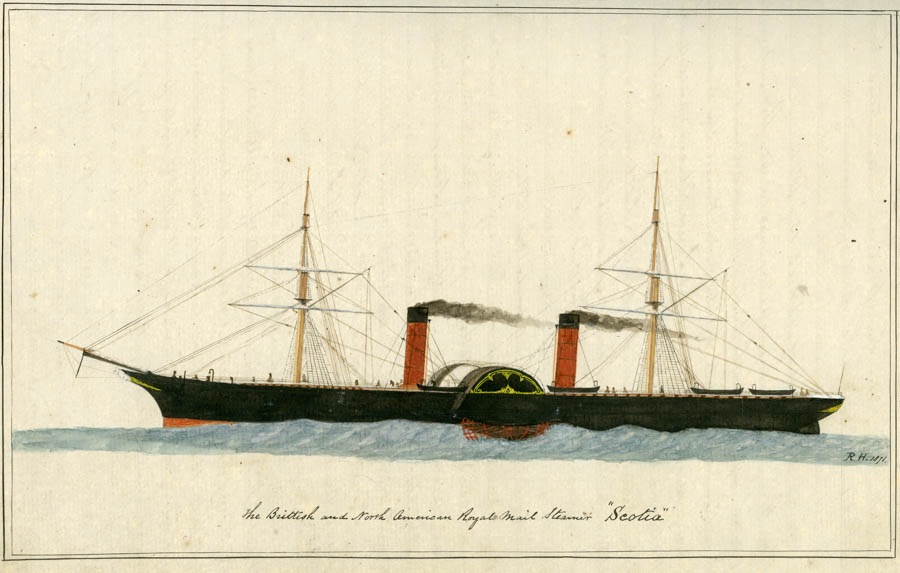

In April 1870 I joined the Cunard Mail service in Liverpool and in the Mail steamer Tripoli had the ill luck to see her run on a reef of rocks near Boston. In this high class service I was satisfied with my advancement in it. I joined it as 4th officer so far as I attained, but an inexorable rule of the company – which in effect was no officer in the service should be advanced to the post of 1st officer in the mail steamers unless such officer has been in command of a ship previously – precluded me from further promotion than second officer. So that I reluctantly resigned the service in 1874 to seek new fields in the hope of further advancement. My time in the Cunard service was agreeable, particularly in the Scotia and steam yacht Hebe. The former ship in her day was the fastest and also the largest steamship crossing the Atlantic. She carried the elite of the travelling public and pick of cargoes: case in bale goods only. Her voyages were made during the summer months only. Briefly this fine ship at the time I refer to was the finest specimen of marine architecture in the merchant marine. Her engines were monuments of engineering skill and she was a most comfortable ship in heavy sea or gale of wind. My chief indulgence in this vessel was the privilege her officers enjoyed have having what is termed three watches, ie. four hours on duty and eight off when the weather permitted or was clear. To appreciate this luxury few but a seaman can do it justice. A treat such as this had never come in my way at sea previously.

Sailing with the Cunard owners

The cruise in the steam yacht Hebe during the winter of 1871 – 72 was indeed a unique experience to me. This beautiful craft was the family yacht of the MacIver’s – owners of the Cunard ships. She was roomy, fast and elegantly furnished and then at the disposal of Mister John MacIver and family. He was a great invalid and sought health by cruising throughout the eastern part of the Mediterranean and at sundown anchored in most out of the way places where pure air and quiet could be secured. We were seldom under weigh before sunrise or after sunset. I joined this yacht in Port Piraeus, Athens, on the 31st of December 1871. During the whole time I was serving in her as first officer it was one of continued daylight cruising. MacIvers were wealthy folk and had large estates in Malta where they always wintered. On leaving the Hebe at Malta I returned to Liverpool and rejoined my favourite ship Scotia. I note these references to the Scotia and Hebe by way of emphasising those memorandums already recorded in their respective pages in this log book, repeating how great was the pleasure and satisfaction I felt while serving in these two most opposite class vessels in size speed and employment.

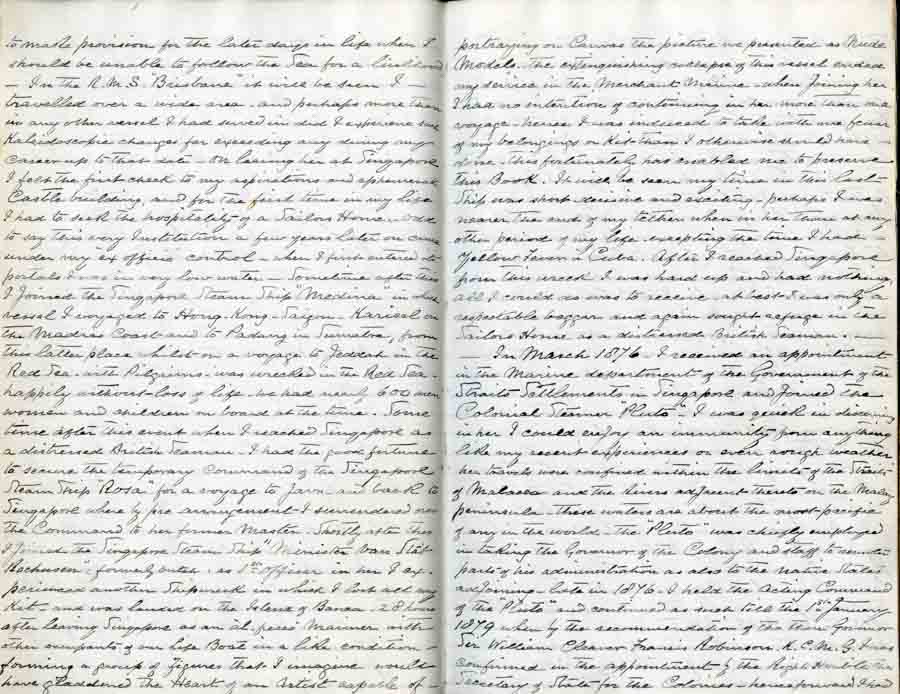

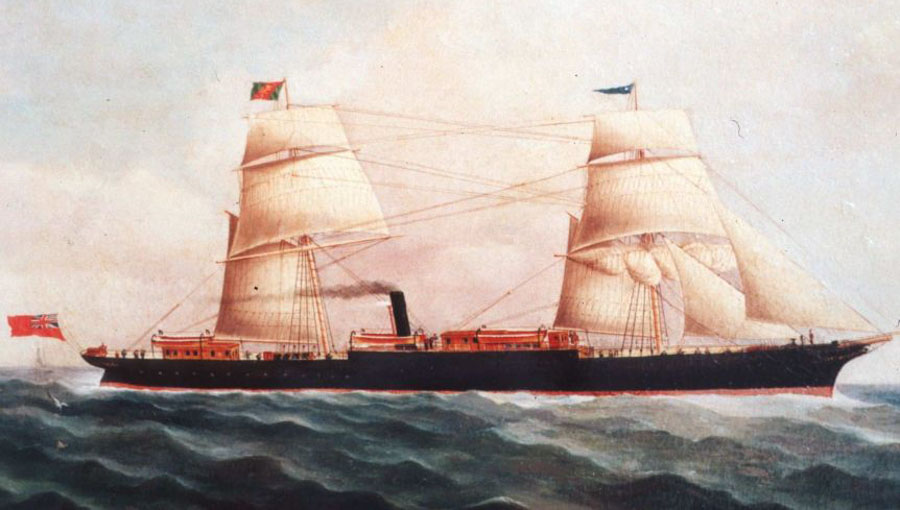

Through the interest of the McIvers I obtained an appointment in September 1874 in the Eastern and Australian Mail Company’s new steamer Brisbane then fitting out in Glasgow. On my joining this ship I felt a determination to remain out east and if possible to succeed in the endeavour to make provision for the later days in life when I should be unable to follow the sea for a livelihood. In the RMS Brisbane it will be seen I travelled over a wide area, and perhaps more than in any other vessel I had served in did I experience such kaleidoscopic changes far exceeding any during my career up to that date. In leaving her at Singapore I felt the first check to my aspirations and ephemeral castle-building and for the first time in my life I had to seek the hospitality of a sailors’ home. Odd to say this very institution a few years later on came under my ex officio control. When I first entered its portals I was in very low water.

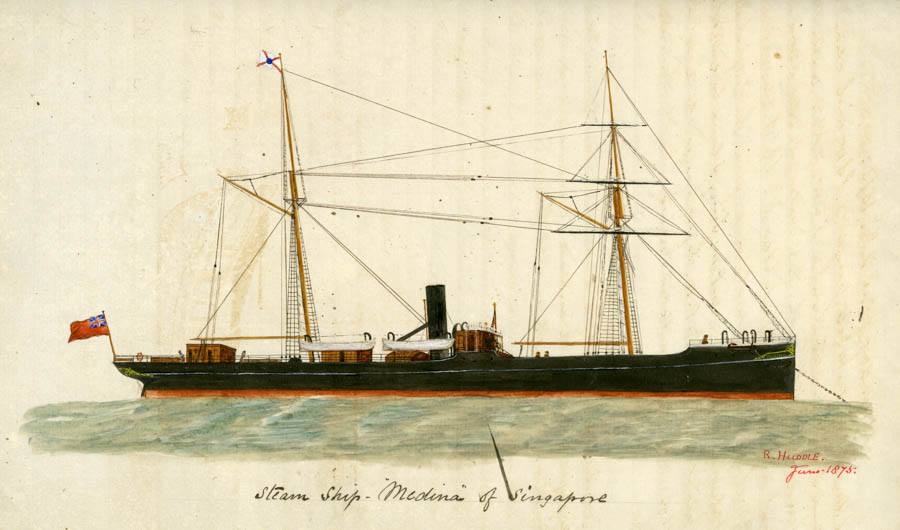

Sometime after this I joined the Singapore steamship Medina in which vessel I voyaged to Hong Kong, Saigon, Karaical on the Madras coast and to Padang in Sumatra. From this latter place whilst on a voyage to Jeddah in the Red Sea with pilgrims was wrecked in the Red Sea – happily without loss of life. We had nearly 600 men women and children on board at the time.

Sometime after this event when I reached Singapore as a distressed British seaman I had the good fortune to secure the temporary command of the Singapore steamship Rosa for a voyage to Java and back to Singapore where by prearrangement I surrendered over the command to her former master. Shortly after this I joined the Singapore steamship Minister Van Staat Rochussen – formerly Dutch – as first officer. In her I experienced another shipwreck in which I lost all my kit and was landed on the island of Banka – 28 hours after leaving Singapore – as an alfresco mariner with other occupants of our lifeboat in a like condition, forming a group of figures that I imagine would have gladdened the heart of an artist capable of portraying on canvas the picture we presented as nude models. The extinguishing collapse of this vessel ended my service in the merchant marine. When joining her I had no intention of continuing in her more than one voyage, and so was induced to take with me fewer of my belongings as kit than I otherwise should have done. This fortunately has enabled me to preserve this book. It will be seen my time in this last ship was short, decisive and exciting. Perhaps I was nearer the end of my tether when in her than at any other period of my life excepting the time I had yellow fever in Cuba.

After the shipwreck

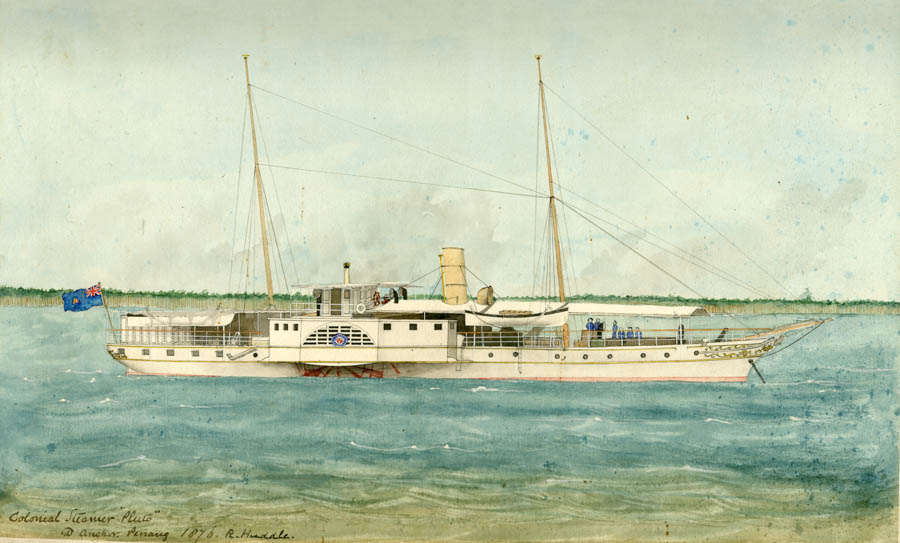

After I reached Singapore from this wreck I was hard up and had nothing. All I could do was to receive. At best I was only a respectable beggar and again sought refuge in the sailors’ house as a distressed British seaman. In March 1876 I received an appointment in the marine department of the Government of the Straits Settlements in Singapore and joined the colonial steamer Pluto. I was quick in discovering in her I could enjoy an immunity from anything like my recent experiences – or even rough weather. Her travels were confined within the limits of the Straits of Malacca and the rivers adjacent thereto on the Malay Peninsula. These waters are about the most pacific of any in the world. The Pluto was chiefly employed in taking the governor of the colony and staff to remoter parts of his administration as also to the native states adjoining. Late in 1876 I held the acting command of the Pluto and continued as such till the 1st of January 1879, when by the recommendation of the then Governor Sir William Cleaver Francis Robinson HCMG, I was confirmed in the appointment by the Right Honourable the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Henceforward I had the rank, pay and entitlements appertaining to the office. After an enjoyable experience in this vessel she was late in 1881 pronounced unfit for further service and sold by public auction. My occupation then for a time was gone – at any rate till the new steamer replaced her. The government granted me leave to return to England and bring out to them their new ship when it was ready. I left Singapore in the French mail steamer Amazone on the 9th of January 1882 for Marseilles, calling at Colombo and Aden en voyage, arriving at Marseilles on the 6th of February and took train to Paris, reaching there at 5:00 am on the 7th and remained onshore seeing all I could till 8:00 pm when I took train for Calais and arrived at Dover 3:00 am next morning. In passing up the gangway from the Dover packet to the Admiralty pier I passed my brother William who was waiting to receive me after an absence of upwards of 12 years. Neither of us recognised each other. I met him two hours afterwards and gathered from him he saw me but I was so unlike what he imagined me to be that we passed each other unnoticed.

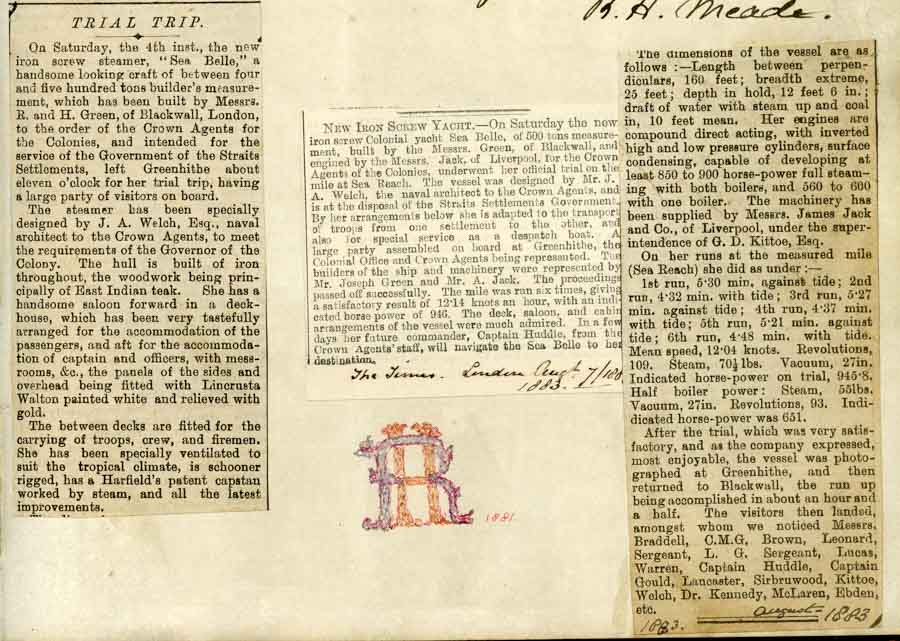

Construction of the Sea Belle

During my stay in London I was literally more or less occupied in watching the construction of our new steamer Sea Belle building at Blackwall by Messrs Green and in the identical yard where my first ship Prince of Wales was built 41 years previously. An odd coincidence that my first and last ships in which I served should both be built in the same yard. On the morning of the 28th of August 1883 the Sea Belle left the East India dock and proceeded towards Gravesend in charge of pilot. After I had seen her fairly on the way I returned to town and bid a fond adieu to all, and in the evening took train to Gravesend and joined my ship. At daylight on the morning of the 29th of August got under way and proceeded en route for Singapore. Passed Dover about 10:00 am, landed pilot and my brother in law Harry Major, and had the last communication with the shore – indeed the last look at old England. The weather was wretched, thick with rain, increasing south west gale and nasty sea, so in reality the Admiralty pier off Dover was the final glimpse of our tight little island I had. The wind and sea increased as we proceeded down channel and the weather as thick as soup. Nothing was visible that could assist me to verify the accuracy or errors of the compass, however, when we were about 10 miles west of Ushant I saw its powerful and excellent light which at once proved the Sea Belle’s position. It was then blowing a furious gale from south west and my little ship tumbling about a good deal. When we were halfway across the Bay of Biscay the chief engineer intimated to me that if the weather continued as it then was we should not have sufficient coal to enable us to reach Malta. I at once decided to make a fair wind of it and run into Corunna for coal and shelter and at 4:00 pm on the 1st September anchored in Corunna Harbour after burying at sea our carpenter who had died. That morning we were right glad of this shelter in harbour. I then telegraphed to the Crown agents in London and afterwards heard they were greatly relieved of much anxiety concerning the safety of the Sea Belle. The weather had been very boisterous since she left London and in the harbour at Corunna there were four ironclad frigates of the Spanish Navy riding at anchor which had like ourselves sought shelter there. When the wind and sea had moderated we left Corunna at 8:00 am on the 4th September and proceeded to sea with fine weather, passing Gibraltar at 7:30 pm on the 6th. Too dark to signal the station.

We reached Malta at midnight on the 10th, taking coal and left at daylight on the 12th en route for Port Said, arriving there 10:00 pm on the 15th, coaled and proceeded through the Suez Canal reaching Suez 8:00 am on the 18th September. Throughout the run down the Red Sea the Sea Belle steamed a good 11 knots per hour making course as straight and correct as a needle, having good opportunities of correcting her compass. We arrived Aden 7:00 am on the 23rd, took on board 70 tonnes of coal and left Aden 6:00 pm same day en route for Colombo, experiencing in full force, after passing the island of Socotra, a strong SW monsoon. When we were midway across the Indian Ocean the Sea Belle rolled and wallowed about alarmingly, so much so that the chief engineer ironically hinted to me it was possible the boilers might give way from their fastenings. We arrived at Colombo on the 2nd of October, coaled, and left there the same evening. Had capital weather the remainder of the voyage and arrived in Singapore Harbour 10:00 am on the 9th October 1883 after a trying voyage and glad to be free from the perpetual rolling motion we all had been subject to. The crew were paid off with the exception of the engineers, and a native crew engaged. The ship docked, cleaned and painted and generally furbished up preparatory to taking the governor of the colony on a tour of inspection throughout the settlements and native states, voyaging over much the same ground as I had previously done when in the Pluto. I continued in command of the Sea Belle for a few cruises when Sir Frederick A. Weld GCMG, then Governor, gave me the appointment of acting deputy master attendant Singapore.

Quitting the sea for good

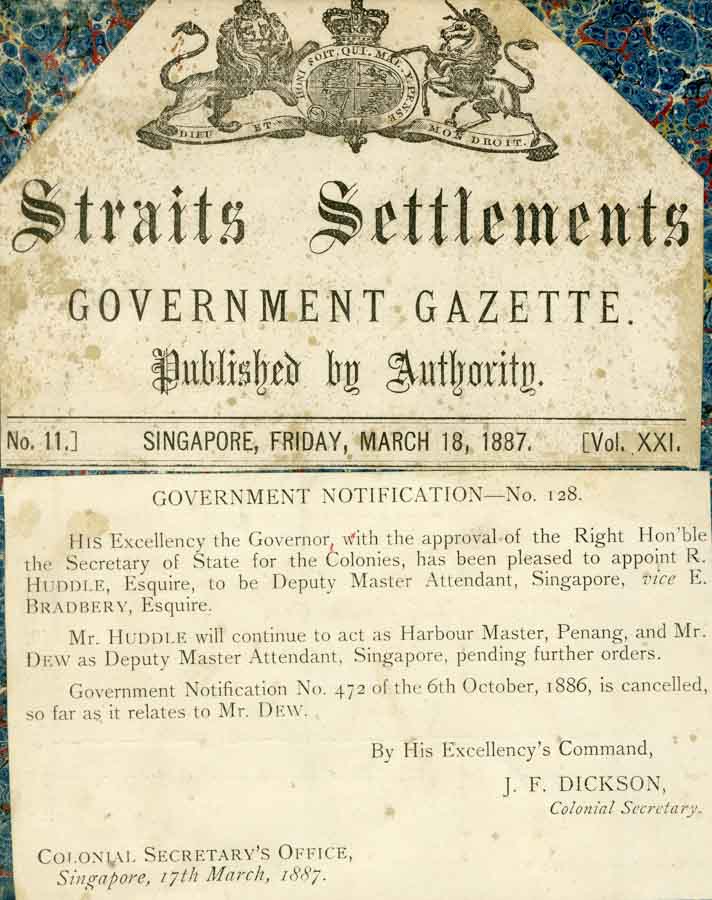

On the 30th of April 1884 I handed over my charge of the Sea Belle to her chief officer Mr C.B. Thorpe and took up my duties onshore as acting deputy master attendant on the 1st of May 1884. I rejoiced in thinking I had the prospect then of quitting the sea for good and hoped no exigencies of the service would arise necessitating my return to the Sea Belle. The sequel to this memoir shows that my appointment to office on shore ended my sea service. My new duties were most congenial to me. I continued as DMA in Singapore till May 1886 when I was further advanced to the post of acting harbour master, Penang, an office much more independent than the subordinate one at Singapore. In Penang I was head of the Harbour Department and had fuller discretionary powers. In short I was my own master, subject only to the authority of the Resident Councillor of the settlement. I remained in Penang till late in April 1887 when I was succeeded by Captain Bradbery – a much more senior officer in the service than myself. I then was ordered to Singapore and reassumed the duties of deputy master attendant to which appointment I was confirmed by the Right Honourable the Secretary of State for the Colonies and gazetted as such. On my receiving official intimation of having the substantive post of DMA I was more rejoiced and content than at any other period of my career. The position gave me a good status in the colony and also in my profession. I was gazetted a JP magistrate, examiner for masters and mates certificates, surveyor of ships, member of the pilot board and other offices some of which carried with them great deal more honour than profit and less profit than credit. However I was supremely satisfied.

An accident, and a visit to Japan

The recollection of some of the incidents and duties of those days are now a pleasing memory with me with one exception – a very serious one. On the 13th of May 1887, midnight, fire had broken out on board the Austrian steamer Titania then at Tanjong Pagar wharf. I was of course by virtue of my office at once called to proceed with my men – about 20 seamen to assist in rendering assistance. Shortly after getting on board I with some of my men, while handling a fire hose fell into the ship’s hold. The fall was so serious that it nearly cost me my life as also the others with me. Some of them were more seriously damaged than myself. I was taken to hospital unconscious and there remained till the following 12th of June. On resuming my duties and getting about it was manifest to me as also to others that my recent accident had very considerably shattered my system. I felt extremely nervous and overcautious with a dangerous hesitation to move about, walk drive, or get on board ship, boat or up and down the graving docks. I carried on my duties in this way, hoping time would restore me to my former state of health and bodily vigour but in November 1887 a medical board recommended me to have three months’ holiday. This the government gave me with full pay and I left Singapore in the French mail packet Eva on the 18th of November, bound for China and Japan, calling in at Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Kobe and Yokohama – reaching this letter port on the 5th of December 1887, feeling improved in health by the voyage and very much colder weather. I took up rooms in the Grand Hotel Yokohama. During my stay in Japan I got about freely, visited many places and objects of interest within a radius of 50 miles. I spent some time in the Hills of Miyashita and Hakone. The mineral hot water springs around this neighbourhood are said to possess qualities capable of curing all the ills that flesh is heir to. I tried them all. Their curative effect on me was nil. Frequently I took train from Yokohama to Tokyo – the capital of Japan – with the aid of guides. On these occasions I was able to see all that was interesting in and around this huge city.

These guides are men of education – speak English fluently and write it. They are licensed by authority: the charges fixed by regulation, and are moderate. During my stay in Yokohama I became acquainted with an old returned Dutch ship master by name Moordoch Heght. His great hobby was fire extinguishing appliances. He informed me he had lost all his family in great fire in Holland and now he applied his mechanical genius – not a little – in practically applying it to the perfection of a useful and handy portable fire pump. He had so far succeeded that his pumps and hand fire engines became widely used throughout Japan. Later on in Singapore, through representations I was able to put forward, the dock companies there ordered from my old friend 30 of his hand fire engines. I mention this en passant – showing that in return for the hospitality I received at the hands of Mr Moordoch Heght I was in a position afterwards to tangibly repay him. His engines were valued at $250 each. I left Yokohama on the 29th of January 1888 in the French mail packet Yang-tse en route for Singapore, calling at the same ports as I did on the upward journey. Arrived at Singapore on the 17th of February and resumed my duties feeling much improved in health. On the 27th of February 1888 the master attendant captain Ellis – owing to impaired health – left for England with the intention of retiring from the service. I was then appointed and gazetted acting master attendant Straits Settlements and carried out those duties in conjunction with my own till 12 May 1888 when the new incumbent of the office – Commander CQG Crawford RN – arrived from the Mauritius in HMS Imperieuse and took up his duties as master attendant, he having been promoted by the Secretary of State from the post of harbourmaster Mauritius to that of master attendant Straits Settlements. I then reverted to my own post of deputy master attendant. My health was again deserting me. The work I had been having was nigh becoming my master so that I was very glad to be relieved from some of it. My time with Captain Crawford passed much more agreeable than it did during the regime of his predecessor though my health and tone in a way seemed receding and in December 1890 the medical officers of government again recommended me to get into colder latitudes for 3 months.

More descriptions of Japan

Government again gave me leave with full pay. On the 26 December 1890 I left Singapore in the French mail streamer Saghalien for China and Japan with the hope of recruiting my health and returning to my duties in a better condition all round. I arrived at Kobe Japan on the 9th of January 1891 after calling as usual at Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai. Took up my quarters at the Hiogo Hotel Kobe. During my stay here I journeyed by road and rail to various places of interest within 50 miles of Kobe. Stayed several days in Osaka and also in Kyoto. The former city is one of the largest in the Kingdom – a very beehive of industry. Kobe is the Liverpool of Osaka. The latter has half a million inhabitants; a Japanese Manchester and Birmingham rolled into one with factories and cotton mills. The latter takes the lead, filled with the latest machinery and lit with electricity. The Osaka mint – over which I was shown by one of the officials – is one of the three most complete in the world. All the coins – gold, silver, copper and nickel are produced there and entirely managed and worked by the Japanese. The Japs indeed shrink before no task, however exhausting; before no problem however arduous and his labour could be bought for a fractional part of the price paid in England. He can turn out an ironclad or a delicate scientific instrument. The Japanese try everything and have tried to raise sheep but that has proved impossible. The indigenous herbage does not suit them and they soon fall off in condition and die. Besides, to support a crowded population of 42 million all the good land is required for food products. The Japanese are most industrious people. Their genius for trade is freely expanded. They have an insatiable appetite for work which is no hardship to them but a natural condition. Whatever they do is done with a will, carried out with unswerving closeness of application and done well. Kyoto – another large city in which I spent some days – was formerly the residence of the Mikado. The city abounds in magnificent Shinto and Buddhist temples. The grounds of some of these enclose large gardens in burial grounds for the priests and other accessories such as belfries, treasure houses, libraries and rare specimens of armour and lacquerware. I was, with the assistance of a guide, shown over numerous silk factories, potteries and porcelain works, metal workers’ shops, ivory carvers and embroidery workshops, schools and many other interesting sites not the least of them being the crematorium – most modern and complete in its appointments. In my visit to it I saw no less than six bodies being cremated at the same time – of course I mean in as many different ovens.

The pleasures of my holiday in Japan were somewhat tarnished in consequence of very cold weather, the thermometer was frequently below freezing point so that riding about in a jinrikshaw – the usual mode of getting about throughout Japan – was not an agreeable pastime when one’s nether limbs were benumbed with cold.

In the Hiogo Hotel Kobe my rooms were large and exceedingly comfortable, with a fire and electric light, and when the weather prevented me going out I could at all times be interested indoors. I had a number of navigation papers as examples to solve and prepare. These I delighted to work out; they would serve as ready papers to simplify and facilitate that part of my work in Singapore relating to the examination for masters’ and mates’ certificates. I left Kobe on the 3rd of March 1891 in the French Mail packet Natal and bid adieu forever to a country in which I found infinitely more amusement than in any other I had visited. The people are delightful and the climate superb. My allusion to the cold weather which I felt trying should be understood as applying only to one who had just been rapidly transported from a normal temperature of 85 degrees two one about 30 in the space of 19 days. This should readily explain the discomfort I felt in my change of surroundings.

Life in Singapore

I arrived in Singapore on the 17th of March 1891 and spent 24 hours on shore in Shanghai en voyage. On resuming my duties as usual I felt better set up. In January 1892 the master attendant left for England on urgent private affairs. I was then again appointed acting master attendant and gazetted as such on the 12th of April 1892 and continued as such till the 24th of April 1893 when Captain Crawford RN returned from leave and took up his duties, relieving me from a large portion of my work. I had no reason then or afterwards to feel otherwise than satisfied. The Governor, Sir Cecil Clementi Smith GCMG expressed to me personally he was satisfied with my work and placed that opinion on record where I suppose it now remains amongst the archives of the Straits Settlements Government. At intervals between January 1892 and April 1893 it was evident my health was fast receding and I felt as if as it were nigh played out. The Governor suggested to me I should take long leave and rest when the master attendant returned to duty and as soon as Captain Crawford arrived I sent in my papers for 12 months leave. This was granted and after a few weeks further continuation in office in order that the master attendant should be settled down to work, I left Singapore on the 27th of May 1893 in the P&O steamer Shanghai and received a good send-off from a number of friends and many others.

Captain Crawford took me off to the steamer and when her anchors weighed I bid him goodbye and had the last look at Singapore and its surroundings. My appointment to and tenure of the office of the post of deputy master attendant and acting master attendant in Singapore was gratifying to me. The duties suited me admirably and pari passu kept me in touch with shipping and the endless variety of incidents arising in connection therewith. When I say there is about 4000 ocean-going steamships entering and leaving Singapore Harbour yearly, besides a very large number of sailing ships and native craft, it can easily be imagined that the work of the port officers are no sinecure. Every vessel entering the harbour is by law bound to have communication with the harbour office. Singapore, like Penang and Malacca, is a free port. There are no other charges on its shipping than the lighthouse dues.

Not the least of my duties were those in a magisterial capacity which I was called upon to deal with. These were often troublesome and vexatious. I had neither the taste or appetite for arguing legal details. Perhaps luckily for me lawyers were seldom engaged on cases upon which I had to adjudicate. However I felt what I lacked in legal knowledge was compensated for by a full acquaintance of the vagaries of seamen and firemen which I possessed, and invariably managed to settle their disputes in a way generally accepted as satisfactory to all except of course to those who of necessity were sent to “chokee” – prison.

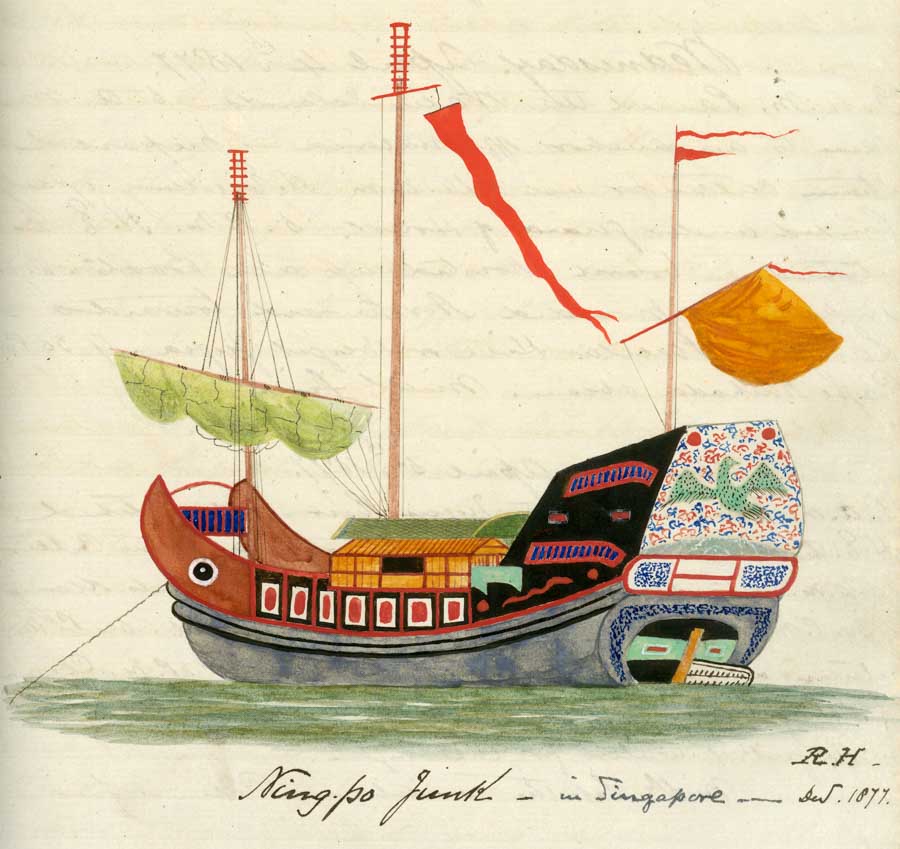

My routine duties commenced about 5:00 am when I invariably cruised around the harbour in a steam launch visiting passenger ships and vessels in drydock for repairs. By 9:00 am returned to my quarters and in office by 10:00 am to 4:30 pm. These journeys around the shipping in the harbour and at the wharves were never monotonous, being varied by new arrivals and departures of vessels both European and native craft – the latter of the most varied types from China, Siam, Java and the numerous spice islands in the eastern archipelago.

Lighthouse visits

My visits of inspection to the lighthouses were all times an agreeable duty combined with recreation. For this special work i had the use of a steam tender – Horsburgh – exclusively employed for lighthouse service. One of our lighthouses was 200 miles distant from Singapore. A day or two spent at these establishments was always a pleasant diversion.

The island of Singapore is about 30 miles long and 14 miles broad, with good roads. It is not very productive but its geographical position makes it the great centre and receiving port of call for all vessels from Europe, India, China and Japan. Its population is about 200,000 consisting of Malays, Chinese, Europeans, Eurasians, natives of India, Arabs, Japanese, Bougis and other eastern races. The harbour of Singapore is one of the greatest ports in the world. It is well fortified with batteries carrying heavy guns and has excellent drydocks. In the course of my official duties in Singapore on four separate occasions I had to order the scuttling of two steam ships and two sailing ships which had caught fire in the harbour. No efforts to extinguish it was successful other than by firing a 7lb shot into them on the waterline. The whole this made soon filled them with water and the vessels settled down on the shallow bottom. I also witnessed the execution by hanging of four Malay pirates. These rascals had captured a native craft and brutally murdered and hacked the crew. This happened within 10 miles Singapore. The only survivor of the crew was placed within 10 yards of these pirates when they were on the gallows before the drop fell. During my long residence in Singapore there are a few places if any that did not sometime or other come under my notice – official or otherwise – as also in Johore, a native state (independent) two miles north of Singapore island.

I had many opportunities of visiting various plantations such as indigo, gambia, pepper, tapioca, pineapple and coconut etc etc. Amongst some of my outings I had with others wild pig shooting, bear shooting with an occasional look for tiger. The rivers and creeks abound with alligators. These afford good sport with a rifle if one holds the barrel straight. I have myself shot upwards of 20 from time to time. In Penang, where I was my own master, I travelled all over the island and spent occasional days on its hill – 2700 feet high – on which is a capital hotel. I also journeyed in the province Wellesley opposite Penang on the mainland. This is a strip of territory 44 miles long and about 10 miles broad forming a part of the colony of the Straits Settlements. This large district is in a good state of cultivation. Rice plantations, sugar cane, tapioca and coconut occupy large areas. There are excellent roads throughout, over which I have ridden from end to end and with others have had good sport after snipe which are abundant in season; one double-barrelled gun bagging as many as 30 couples in about three hours shooting. The island of Penang is about 14 miles long and about 9 miles broad. It has a good harbour and like Singapore is a centre of trade, chiefly from the island of Sumatra and its pepper ports, the Mergui Archipelago as also the native states of the Malay Peninsula. Large quantities of tobacco are raised in Sumatra and trans-shipped to Penang. Tin is largely produced in the native states and is a chief source of revenue. Upwards of 17 million pounds Sterling in value of tin has already been raised and now there is no hint of approaching exhaustion.

Sorry to leave Penang

I was sorry to leave Penang. My residence there was agreeable and when quitting these regions of the eastern land of perpetual summer it was with feelings of regret. I feel bound to admit that had my health permitted my intention and hope was to have continued in active work till I had attained the age of 55 years. Impaired health precluded my doing so hence my retirement earlier. On my voyage home the Shanghai called in at Penang on the morning of the 29th of May. I then landed and spent time on shore with my friends till midnight on the 30th. The steamer then proceeded on her voyage and I had my last look at Penang and its excellent light on Muka Head: one of – if not the best – light in the east, east of Suez at any rate. Owing to its elevation above sea level it can be seen at a greater distance. I reached Colombo on the 5th of June and left again the next day. Had a rough journey across the Indian Ocean, arriving at Suez 4:00 pm on the 23rd June. We then entered the canal in charge of a pilot and with the aid of the electric light suspended and projected from the stem of the Shanghai, we continued on all night through the Suez Canal, arriving at Port Said 8:00 am next morning. Here we heard of the disaster to HMS Victoria.

After taking in coal we left Port Said at noon and reached Marseilles 10:00 am on the 30th of June 1893. Here I spent 24 hours on shore wasting a good deal of forcible and inelegant English chatter. Left Marseille 1:00 pm on the 1st of July and arrived in the Royal Albert Docks, London, at 7:00 pm on the 9th of July 1893 and ended my travels.

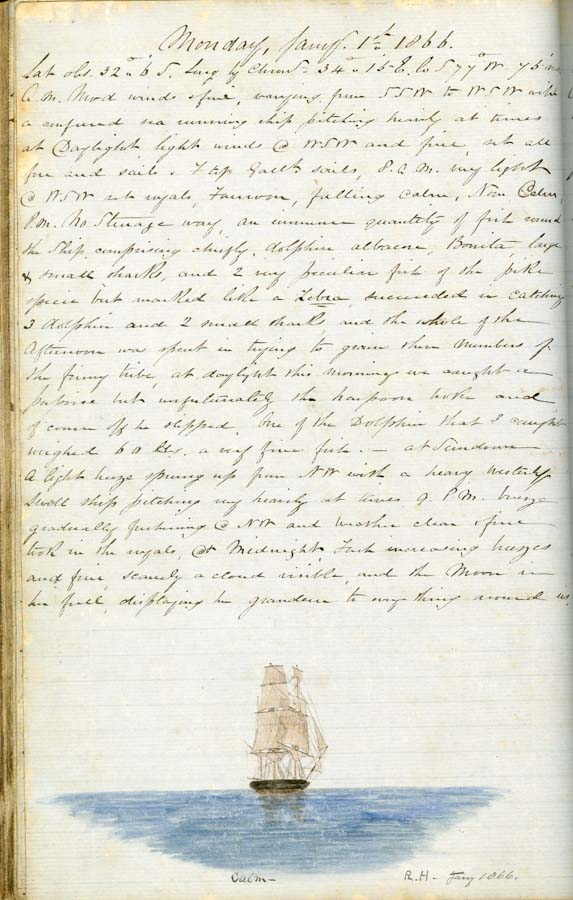

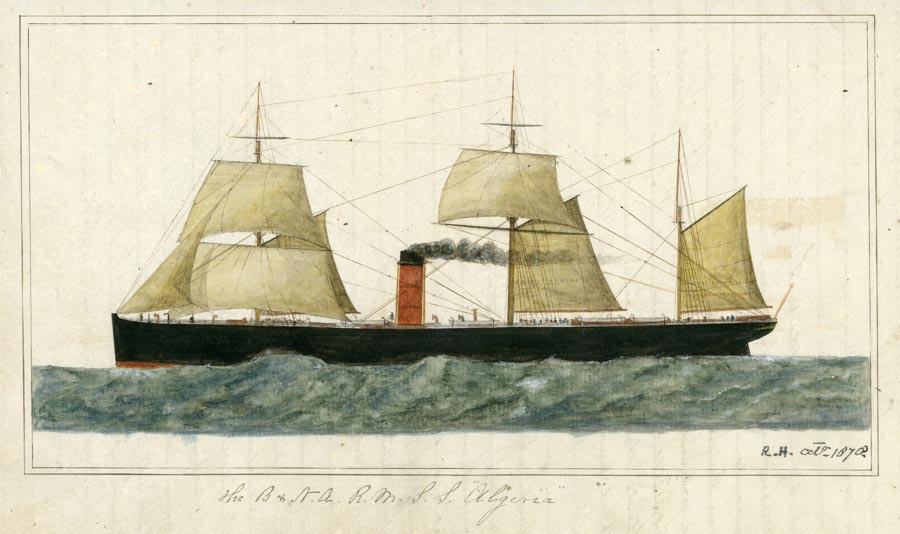

With reference to the memorandums in the body of this log, recording them was at all times a genuine pleasure to me – seldom omitted. It will be noticed throughout the pages no mention is made of the days of detention in harbour. They are of necessity to an officer of a ship void of interest or change other than hard work in preparing the ship for her next journey. The daily notes give more or less details – some more fully described than others. I have tried on a few occasions – perhaps feebly – to do justice to some of the passing events occurring at the time and place wherein they are sit down. The same remark applies to the few sketches. They – if not adorning the pages – might serve, like the finger posts on one’s highway, the purpose of indicating the locality and attract attention. In short my log book records my intimate experiences and no more. As a diary it has no pretensions in setting down all that one feels or thinks or has seen, but notes on episodes and impressions conveyed to a man with his eyes open and an observer in interesting things and interesting people with an unfading interest in keeping my log written up. This log book has served me as a simple mental exercise with no attempt at felicity of diction. It is an effort at expressing my ideas arising at the time and place they are noted down, and only those made during my voyages in the barque Magdalen and steam ships William Penn, Bellona, RMS Tripoli, Algeria, Scotia, steam yacht Hebe, RMS Batavia, Brisbane, SS Rosa, Medina and Minister van Staat Rochussen and my much-liked Pluto when my luck was in the ascendant, and needless to say I put forward my best efforts to keep it there. I had many agreeable excursions and adventures with her and I’m sorry now they – as also some others – were not more fully written at the time they occurred. On occasions when the Pluto was anchored off the Malay coast I – with an officer, boat’s crew, gun and rifle – would go on shore and wander in the jungle bordering the beach and within a few minutes ramble would be surrounded by high tangles of bramble and coarse brushwood and undergrowth that one could not move about freely or even see daylight.

About the logbook

I have previously alluded to the time I served in the sailing ships Prince of Wales, Alfred, Anglo Saxon and Owen Glendower and I need scarcely add now that my log book has voyaged with me at all times since its commencement till the date of its concluding pages with the exception of the time elapsed between the day of the wreck of the Medina in the Red Sea on October 1st 1875 till I reached Jeddah on the 19th of the same month and on one other occasion in Singapore where I left it on shore during that not-forgotten voyage in the steamship MVSR.

When I left England with the Sea Belle in August 1883 I did not care to again risk it at sea and left it in the care of my brother William. Hence it was not possible for me to continue writing it up as I hitherto had done from time to time. This break in its continuation a priori I regret as after leaving England in the Sea Belle, notes of my experience since then – had they been added to this book – would I believe enhance the reading, particularly with reference to the time I had on board the Sea Belle during the voyage out to Singapore. This craft rolled and tumbled about alarmingly enough to take the edge off the keenest appetite of anyone desirous of either writing, reading or giving oneself up to the dolce far niente of his imaginings. She moved like a pendulum excepting when in perfectly still water. My time occupied onshore in Singapore and Penang between May 1884 and May 1893 was full of interesting episodes but when I quitted the Sea Belle and the sea for good my interest in keeping up my log deserted me insofar that this book was not then available. I wish it had been and here I plead as some excuse for the brevity of many of its memorandums my inability at the time to afford the leisure necessary for writing, and that the duties of an officer on board ship – more particularly in large steamships where a great number of passengers are carried – is such that what leisure time he gets does not readily adapt itself for the purpose of writing descriptive accounts of the various incidents passing under one’s notice during a long experience at sea. Hence many of my notes are like the menu of a sailor’s dinner: not very long.

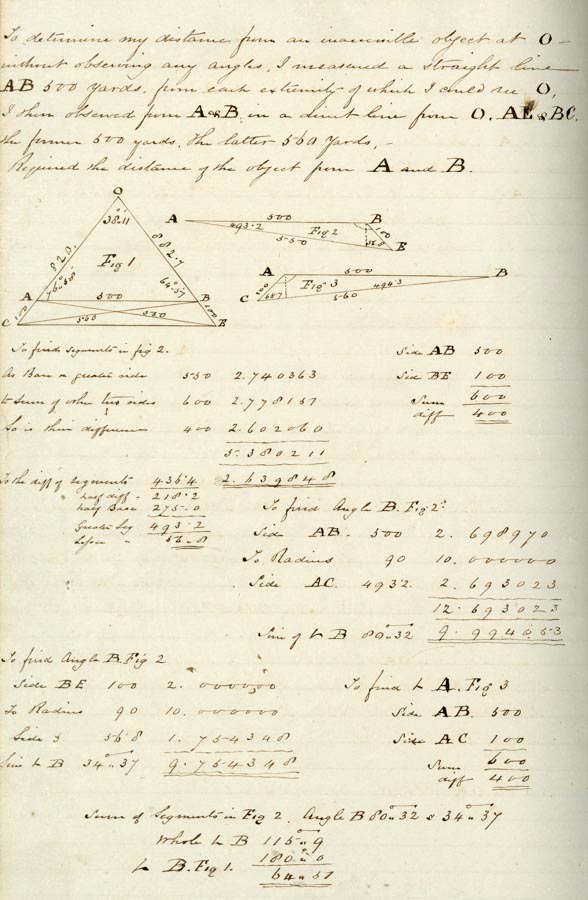

The occasional pages of figures and formulae are solutions to problems in navigation directed chiefly to finding where you are. The other pages speak for themselves. My book, with its errors of omission and commission, may leave perhaps something to be desired. Indeed it would be singular were it otherwise. With these prefatory remarks and pages its raison d’etre explains itself. I submit it en bloc as some record in outline of the weathercock changes allied to the writer during the manifold phases of my travels on sea and land. If its perusal creates in the reader a particle of the interest its writing has afforded me I am content to hope the book may be acceptable to those of my relations and friends in whose kindly care it ultimately finds an anchorage and safe mooring berth. At the close of my career and stepping down from a good position in it I trust my time has not been uselessly occupied. The 40th anniversary of my first entry on board ship seems to me a suitable occasion to bring this chapter to an end and close the book. Though one’s life may be extended for a few years beyond the span of his active work, its record can never be more than a dry appendix and perhaps not worth recording.

Robert Huddle

Sidcup Kent

September 1896

Epic transcription, Greg. Mr. Huddle is now (or soon to be) immortalised in the digital realm… https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.phototimetunnel.com/

That’s interesting, thanks Phil. 🙂