On June 18, 1918, German gunner Herbert Sulzbach noted that “there is an epidemic on, what they call Spanish ’flu, so that even leave has been stopped”. It’s a throwaway war diary line about a virus that ultimately killed more people than the Great War itself. The war is estimated to have killed about 18 million (though that number must be greater when those who died later from the consequences of the war are taken into account), but the influenza pandemic killed between 20 and 50 million in the years from 1918 to 1920.

Sydneysider Eric Evans, in hospital in England recovering from war injuries, reported in his diary on October 26, 1918 – not long before the war’s end – that “the flu is raging and causing ever so many deaths. Many of our boys are suffering.” Four days after the Armistice was signed Eric visited the churchyard near his hospital and noted that: “the place was full of Australians’ graves, the influenza epidemic being responsible. There was also the grave of the matron of Sutton Veny Hospital who died a few days ago.”

German gunner Herbert Sulzbach

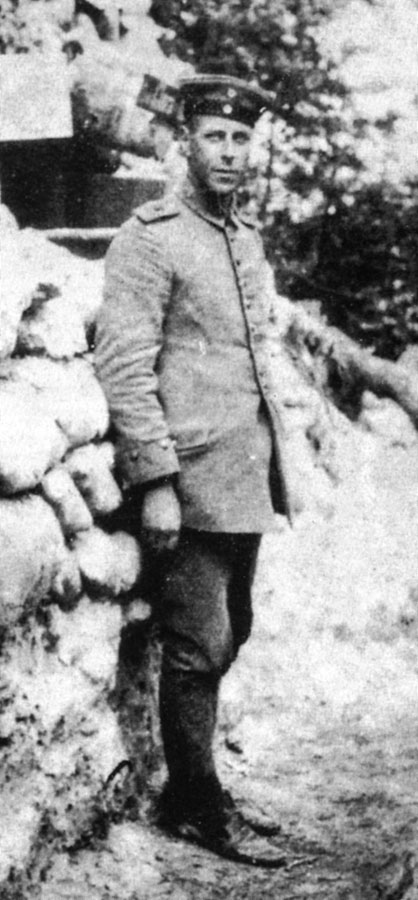

Trooper Ernest Pauls, of Dorrigo

Dorrigo lighthorseman Ernest Pauls arrived home from the war, passing Sydney Heads on March 6, 1919. He was unhappy to learn his ship would be held up because of the epidemic. “We had to undergo a three-day quarantine aboard ship before disembarkation. This has seemed an eternity and altogether a cruel and unjust proceeding considering we are a ship entirely free from disease,” he wrote.

If Australians had been hoping life might go back to something resembling normality following the war’s end, the influenza pandemic dispelled the hope. The virulent flu strain that emerged in the northern hemisphere in the spring of 1918 hit the world in a series of waves over the following two years. Some believe the virus may have first appeared in China as early as 1910, perhaps travelling to Europe with about 200,000 Chinese people forced to labour for the Allies. Soldiers on both sides were badly affected towards the war’s end, and returning soldiers helped the virus span the globe.

By October 1918 it had appeared in New Zealand. Early in 1919 the flu emerged in Victoria, where the state government at first failed to recognise the killer virus, asserting that the early cases were merely normal flu. The NSW Government said much the same thing when its first cases appeared. Across Australia the pandemic is reported ultimately to have killed about 12,000 to 15,000 people and, unlike most familiar strains, it had its worst effect on younger, healthier people. Indigenous people were hit very hard, and the mortality rate in some communities was extremely high.

The symptoms were a sudden rise in temperature, with shivering, headache, pains in the back and limbs and general weakness. If it turned to pneumonia, death all too often followed.

Australia’s medical services had been badly disrupted by the war, and the pandemic stretched the system to its limits. The number of patients needing hospitalisation far exceeded the modest capacity of hospitals, so temporary influenza hospitals were set up in private homes, schools, showground buildings and churches.

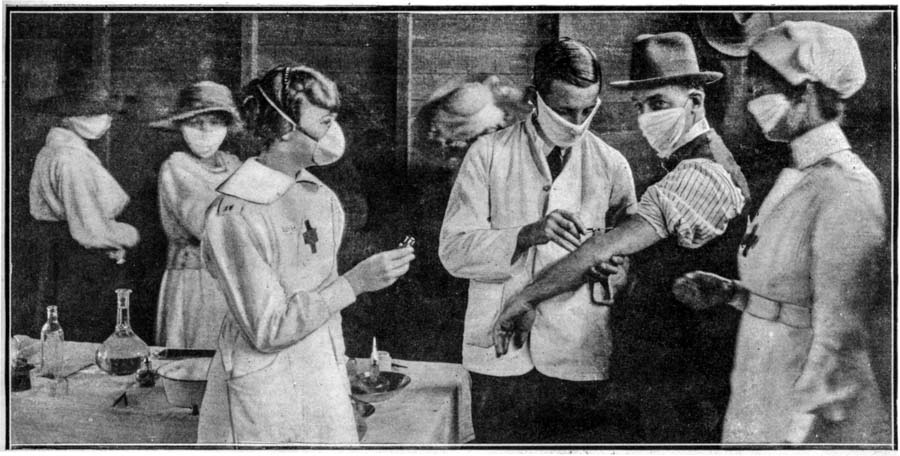

In NSW masks were made compulsory (despite strong differences of opinion as to their value), schools, theatres, libraries and other places where large groups of people might gather were closed. Race meetings were banned, and church services had to be conducted outdoors, kept to 45 minutes duration and those who attended had to keep a metre apart.

Some interstate borders were closed. NSW, for example restricted visitors from the more heavily affected state of Victoria, and many Queenslanders were stranded in temporary quarantine stations at Tenterfield and Tweed Heads.

Newcastle’s major stores required their staff to wear masks, and orders for masks skyrocketed. A finished mask cost fourpence, while the materials to make one yourself cost a penny less. People travelling and working on public transport were required to wear masks, and when some people refused, the government introduced fines.

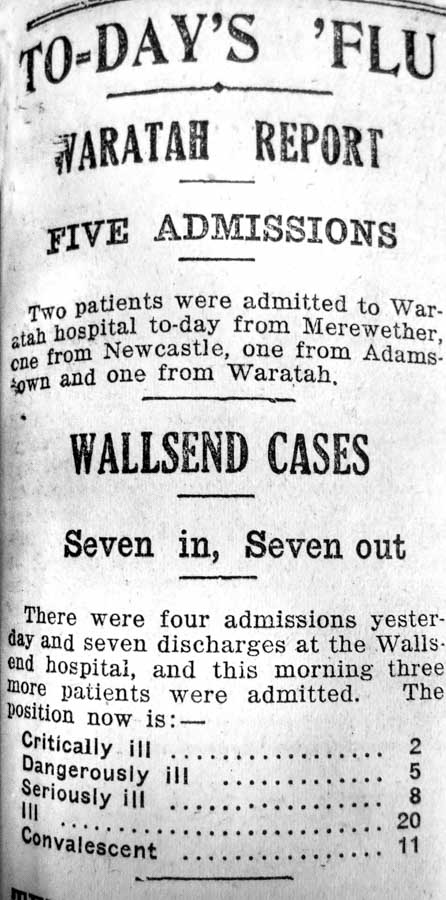

The Hunter Region of NSW suffered its share from the pandemic, and newspapers carried daily tallies of the toll of death and illness, along with reports of special measures to deal with the flood of patients needing care.

The first of the two waves of infection peaked in the region in April 1919. Anzac Day commemorations in 1919 were more subdued than they might have been because of the flu. The NSW Department of Health permitted open-air and indoor services, providing that “all persons attending, other than the officiating clergyman, shall wear masks, and shall be placed not less than 3ft apart”.

Western Suburbs Hospital was converted to an isolation facility for victims of the virus, and so was Wallsend Public School. Over the course of the epidemic Western Suburbs Hospital received more than 1500 cases, of whom more than 150 died.

Interestingly, the captain of a ship in Newcastle Harbour at the time declared that he was treating cases with a teaspoonful of quinine, mixed with two or three teaspoons of whisky or brandy, several times a day.

The government closed down most shops for four days over Easter 1919 to give retail workers a break. They were believed to be particularly at risk, and also likely spreaders of the illness.

The Hunter Region’s eventual tally was just under 500 deaths, with only 85 categorised as elderly or aged under five years.

In the United States about 675,000 people died from the flu, including about 43,000 servicemen. Of the US soldiers who died in Europe during or immediately after The Great War, half were killed by the virus, and not by the Germans.

In a morbid footnote, scientists have extracted parts of the virus from corpses buried in permafrost in northern latitudes and managed to reconstruct the DNA sequence. The value of this achievement remains to be seen.