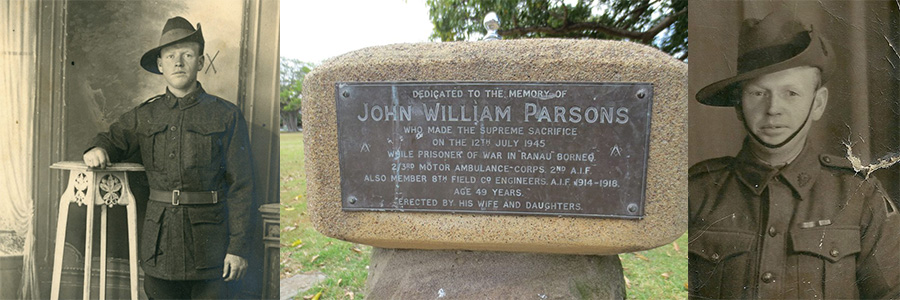

In Gregson Park, Hamilton (Newcastle, NSW), a drinking water fountain stands near the large war memorial. On one side is a plaque that reads:

Dedicated to the memory of John William Parsons who made the supreme sacrifice on the 12th July 1945 while prisoner of war in Ranau, Borneo.

2/3rd Motor Ambulance Corps 2nd AIF

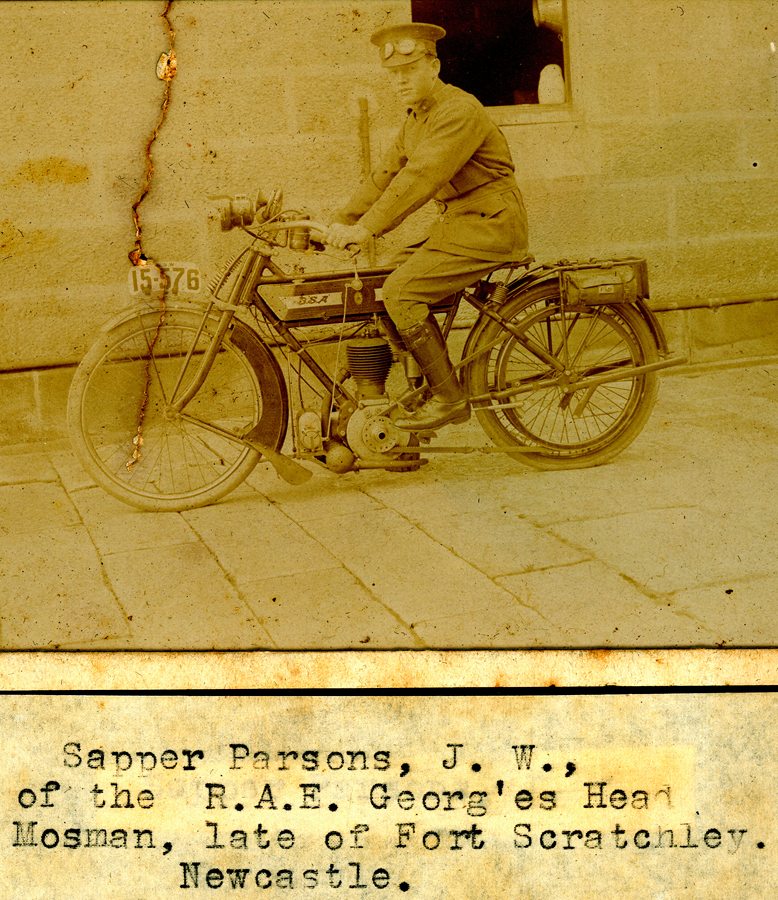

Also member 8th Field Co Engineers AIF 1914-1918.

Age 49 years

Erected by his wife and daughters.”

In truth, the fountain memorialises Jack Parsons and his wife Doris, both profoundly affected by the world wars of the 20th Century.

The story of Jack and Doris starts with The Great War of 1914-1918. Later – when an even bigger war came along – the “Great War” was re-badged as “World War I”. Doris was 16 when the war broke out, and living with her family at Nobbys Road, Newcastle East.

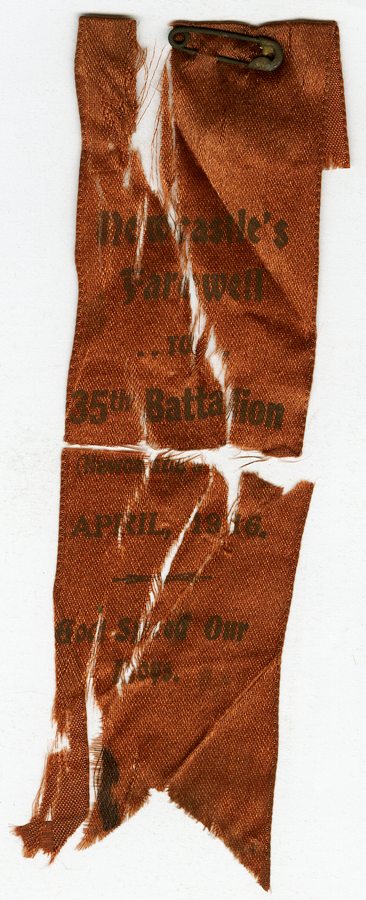

Like many Australian youngsters at the time, Doris Schuck seems to have been caught up in the patriotic fever that swept the country. She preserved quite a lot of memorabilia during her long life, including ribbons, badges, photographs and letters from the time of the war.

Living in Newcastle’s East End, Doris got to know a few young men from nearby Fort Scratchley and she took enough of an interest in military matters to keep up a regular correspondence with a handful of soldiers on active service overseas.

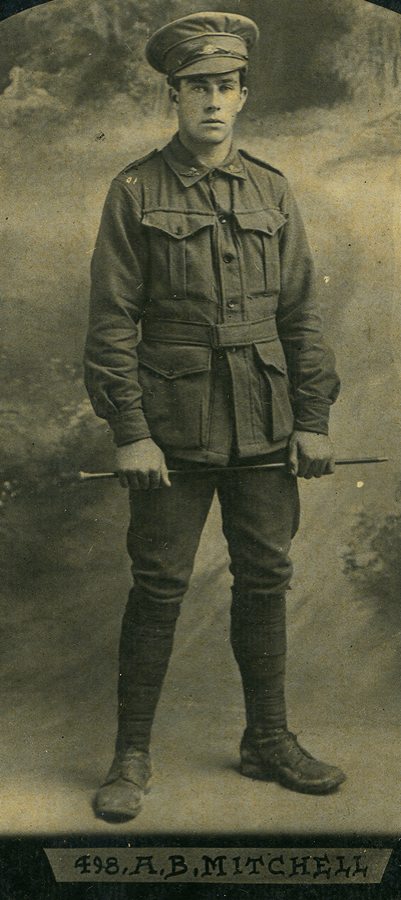

Chief among the recipients of her chatty letters – usually typed – was Alfred “Bruce” Mitchell, a signaller in “Newcastle’s Own” 35th Battalion who had previously been based at Fort Scratchley. Bruce, it seems, may have been Doris’s sweetheart before the war, if the cards and letters between them are any guide. Bruce’s very fond letters to “Dot” or “Dolly” sometimes described hair-raising near-misses in action. Sadly, Bruce was killed by a sniper in February 1917.

Doris also wrote often to Will Weston, an infantryman the 35th Battalion, and it is clear from Will’s letters that the correspondence was very important to him. Doris told Will in June 1918 that she wished she was a boy and could go and fight. She had just put Will’s photo in her locket, she wrote, alongside that of “poor Bruce”. Will was killed in action on August 8, 1918.

Another regular correspondent, perhaps not as close as Bruce or Will, was Bombardier George Gillam, who survived the war and made it back to Australia in 1919.

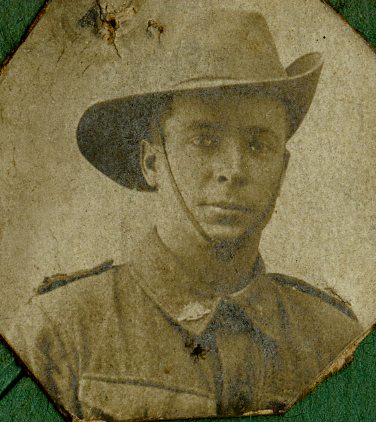

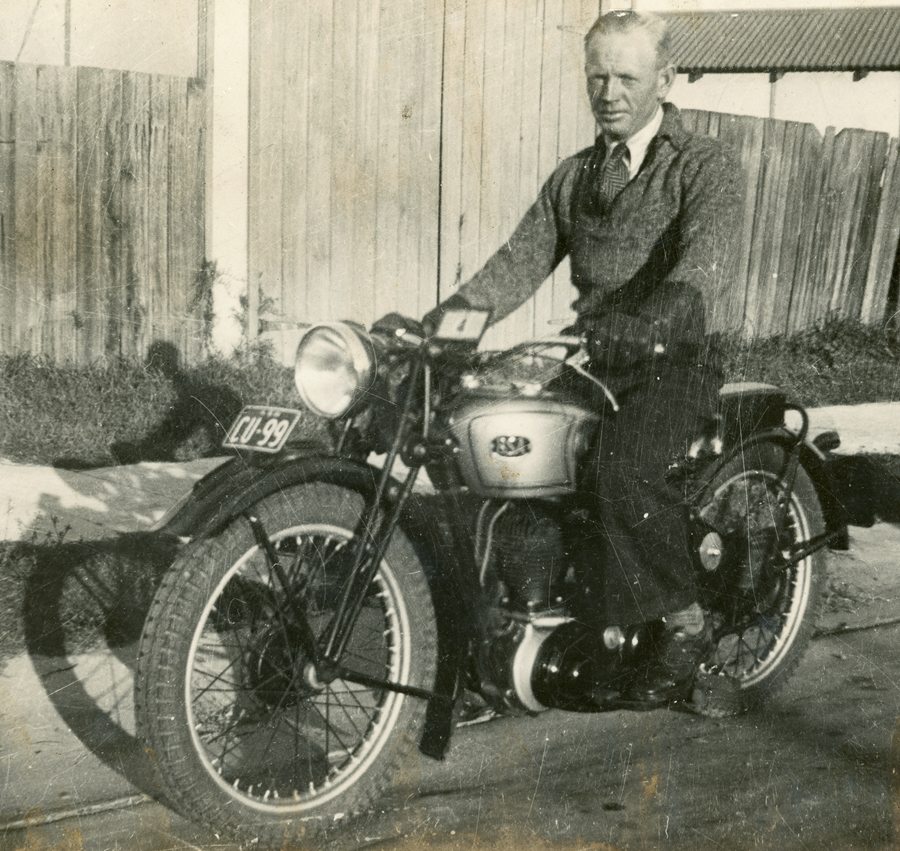

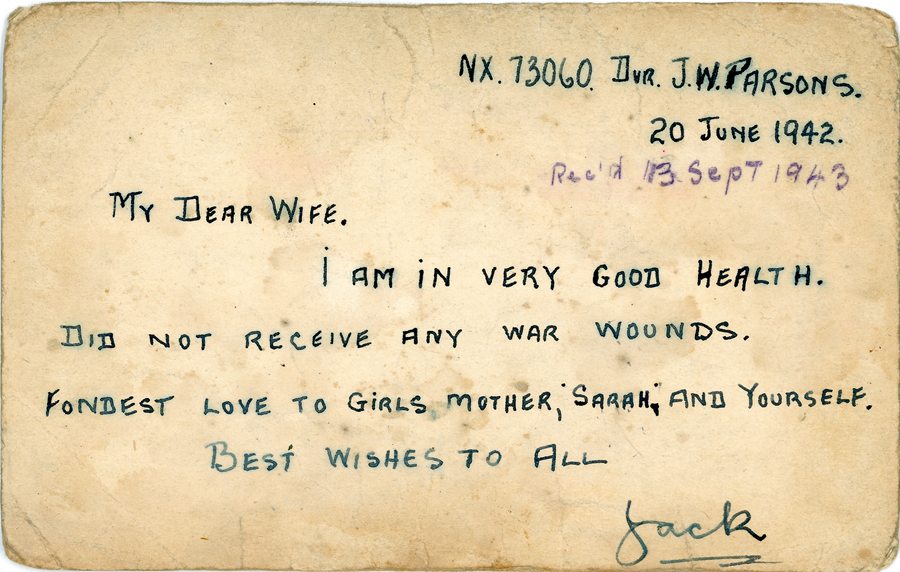

Who knows how Doris’s life might have unfolded had Bruce or Will returned? As fate determined, she was to wed yet another regular correspondent, Jack “Smiler” Parsons, a sapper who enlisted in late 1917 and arrived in England not long before the war ended. Jack had been a guard at Fort Scratchley and it was in that role that he met Doris. He was, like Doris, an enthusiastic writer of letters and cards. The pair also shared an interest in photography.

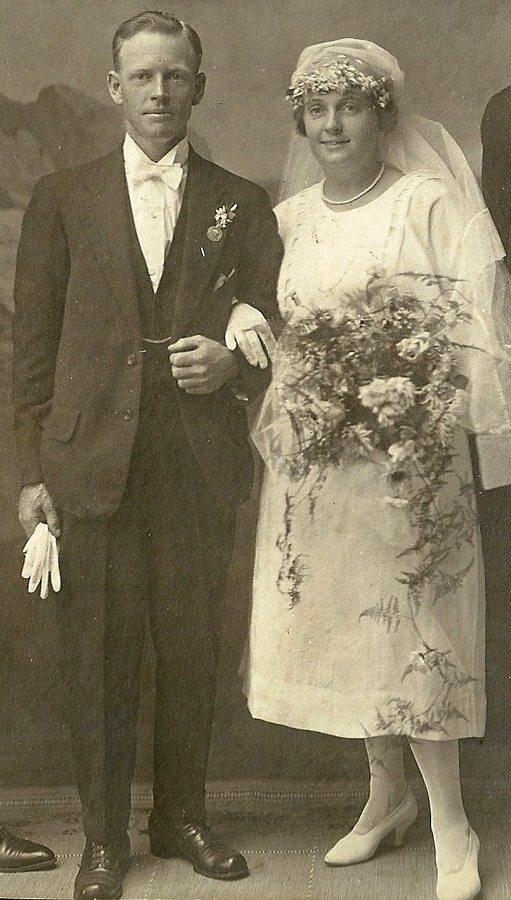

Jack signed his letters “your friend”, but things developed and evidently developed even more when he returned to Australia and went back to work at the David Cohen store in Bolton Street, Newcastle. The pair married in 1922, had two daughters, saved their money and invested in properties around Newcastle. According to family tradition, Jack was also a surprisingly successful gambler, winning one or two substantial lottery prizes.

Unfortunately for the pair – and for millions of other people around the world – another large-scale war arrived.

Jack fudged his enlistment papers in April 1941, claiming a birthdate of 1900 instead of the 1895 date that he used in the previous war. Even if he’d been telling the truth he’d have been elderly by active service standards. He was accepted as an ambulance driver and sent to Singapore in late 1941, just in time to be captured by the Japanese when Singapore was captured in February 1942, along with tens of thousands of others destined to share a similar fate.

Jack was eventually posted missing on July 13, 1942. In the tremendous confusion of the fall of Singapore details on the whereabouts of individuals were hard to get.

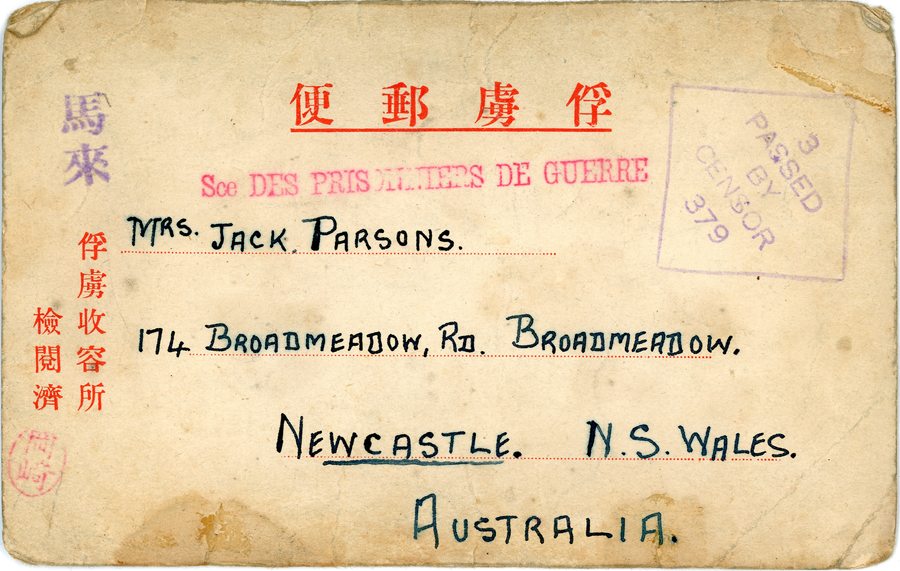

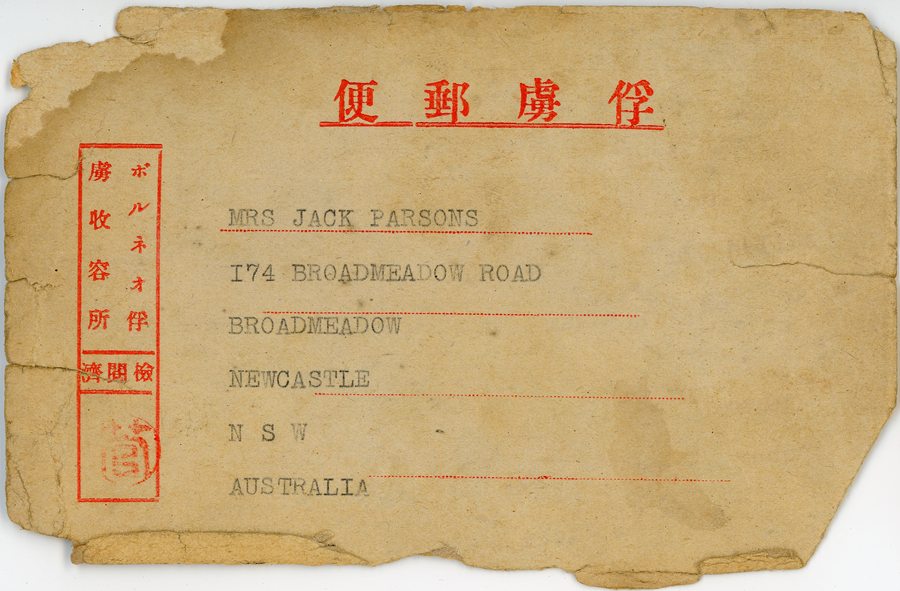

From the point of view of Jack’s family back home in Australia, it must have been a great relief when he was reported to be a prisoner of war on Borneo in April 1943. At least he was alive, not that the scanty cards the Japanese occasionally allowed some of their prisoners to send gave much information. The true horrors of captivity under the Japanese were not known by most Australians until the war was well and truly over, and the fate of many of those imprisoned on Borneo remained a secret for decades after that.

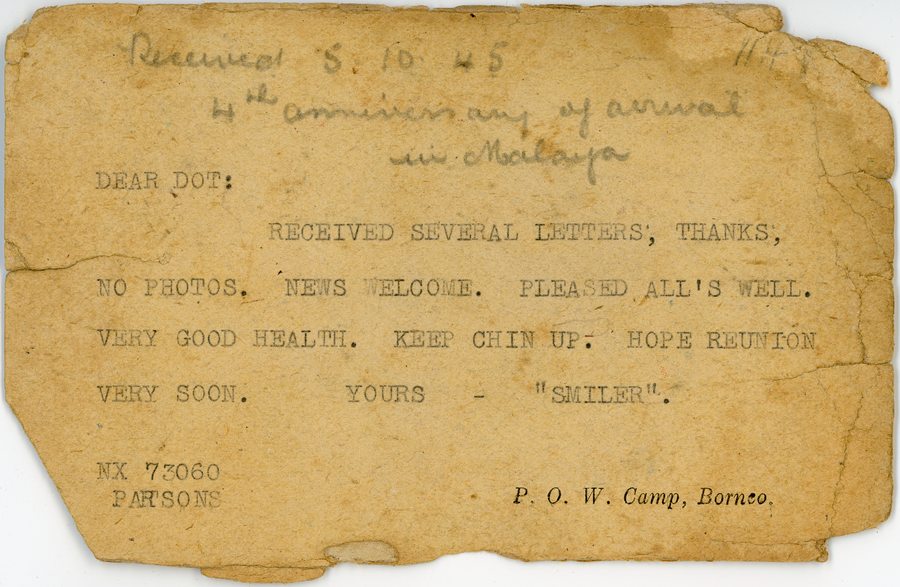

The last card Jack sent from Borneo was received by Dot on October 5, 1945, well after the end of the war in August that year. The card was addressed to Dot by name, stating that Jack had received several letters but no photos. Dot was urged to keep her chin up and look forward to a “reunion very soon”. It was signed off with his nickname, “Smiler”.

The hope this card must have engendered was cruelly false. Smiler, by now aged 49, had managed to survive the notorious Japanese POW camps on Borneo only to be murdered when the end of the war was in sight.

Smiler became one of thousands of victims of the notorious Sandakan to Ranau death marches, where the Japanese marched almost 2500 sick and starving Australian and British prisoners to their deaths. After the war the Australian Government suppressed information about this atrocity for decades, claiming it was trying to spare the bereaved families the pain of learning about the mistreatment of their loved ones.

Only six Australians survived the death marches – by escaping and being helped by local people – and only four of those survived to give evidence at the war crimes trials that followed.

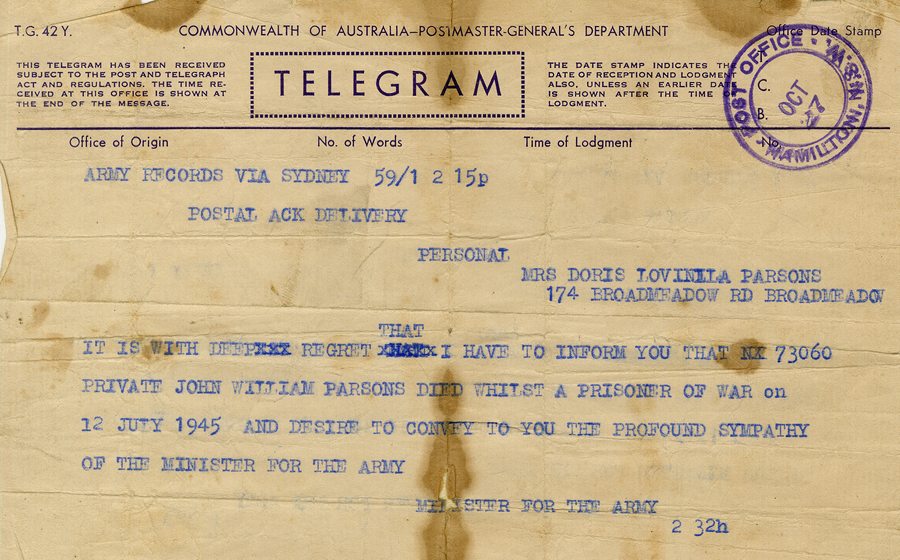

Having celebrated the end of the war in August with great enthusiasm, made greater by the thought of an impending reunion, and then having received a card from Jack in October, Jack’s family was crushed by the arrival of a telegram on October 27 advising his death. The telegram stated that Private John William Parsons had died on July 12, 1945, barely a month before the war ended.

Jack and Doris’s daughter Mavis wrote a short account of her experience of VP Day in Newcastle. Aged 15 at the time and working for the Newcastle Fur Co, Mavis was photographed with workmates leaning out of the windows of the business above Coles in Hunter Street. She described being on the back of a table-top truck in Hunter Street, singing and whistling as the truck drove up and down all afternoon.

“We celebrated thinking my father would be coming home,” Mavis wrote.

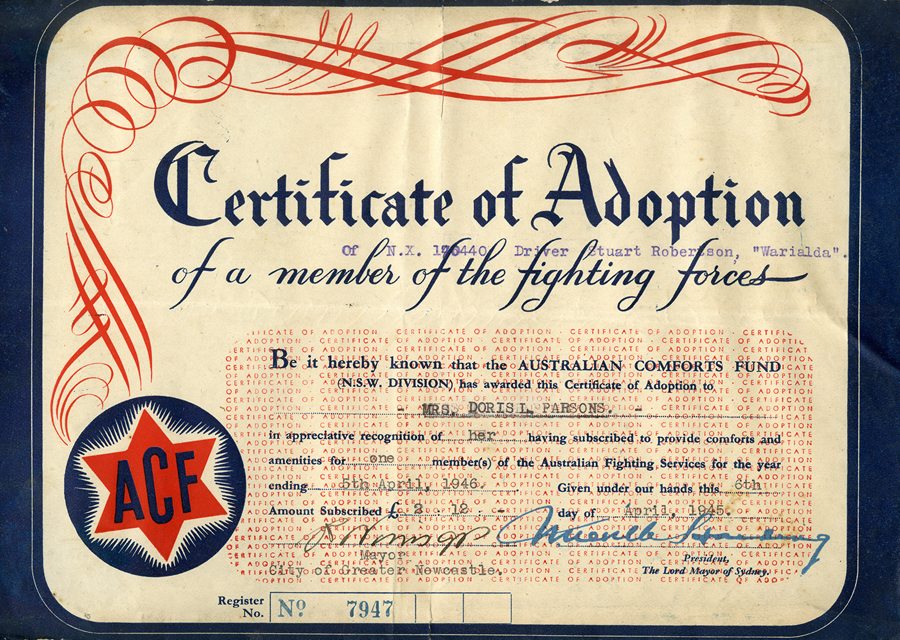

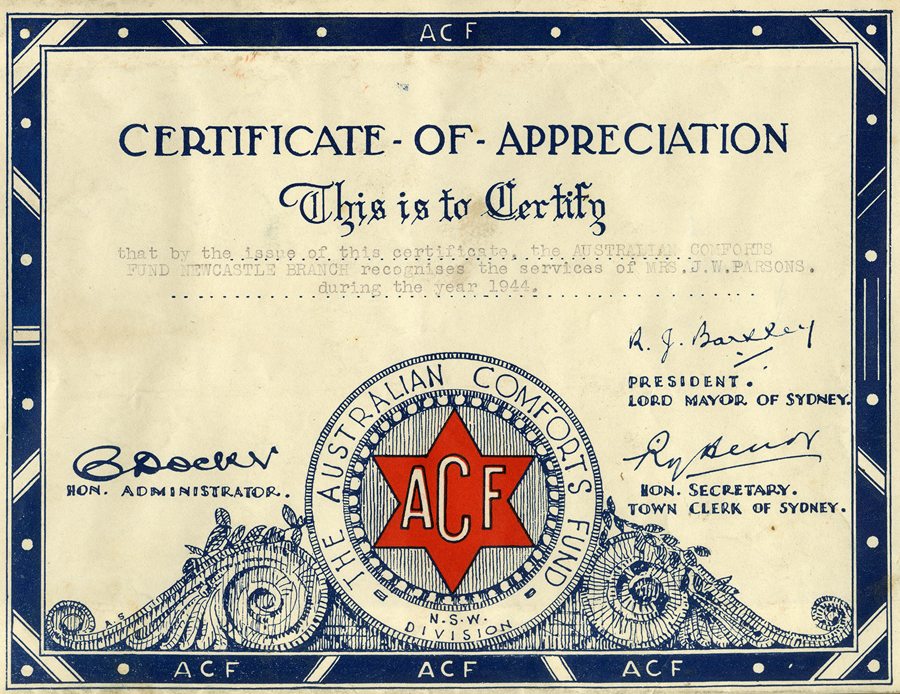

All through the war Doris Parsons had devoted time and energy to the RSL and related causes, helping raise money and maintain the morale of soldiers, as she had done in the previous war.

Her grief at the loss of her husband was profound. Anxious to have him remembered in some practical way, she offered to pay 20 pounds towards the erection of a drinking fountain in Gregson Park, near her home. Newcastle City Council accepted the offer and the fountain was dedicated on November 10, 1946.

Remarkably, Doris also managed to visit Jack’s grave at Sandakan, well before such journeys became routine. She travelled by cargo ship and had just six hours at the cemetery which she spent sitting by the grave under a parasol while local people gave her food and drink. Since then a number of other family members have made the journey, including Mavis and her daughter Kris Eyre. Over the years the grave has been moved and in 2022 all the prisoner of war bodies that have been recovered are buried at Labuan war cemetery. A memorial park is maintained at Sandakan, on the site of the former POW camp.

She has a photo of Doris, Jack’s medals and a photo of Jack.

With thanks to Doris’s grand-daughter Kris Eyre and her husband Stephen for their help in assembling this post.