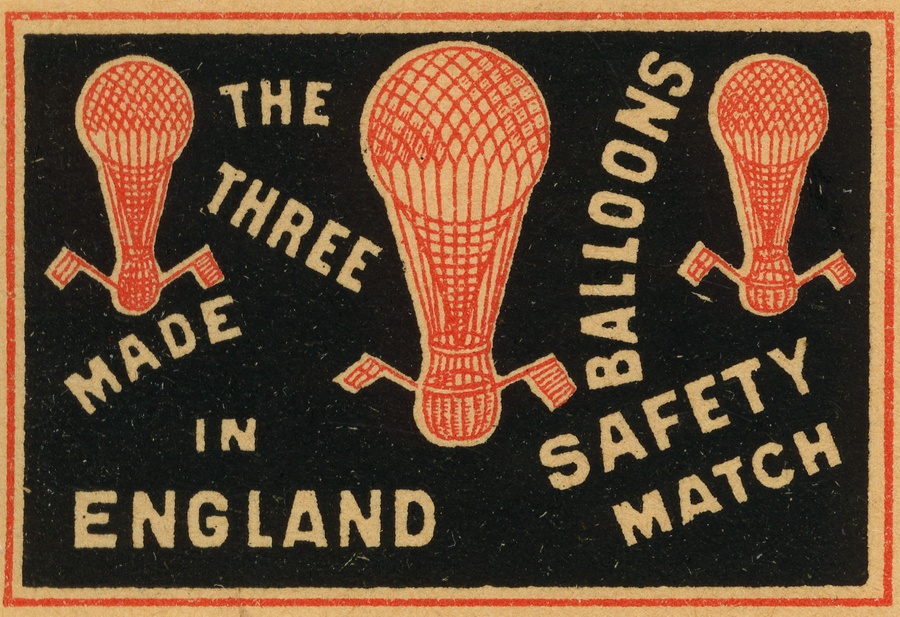

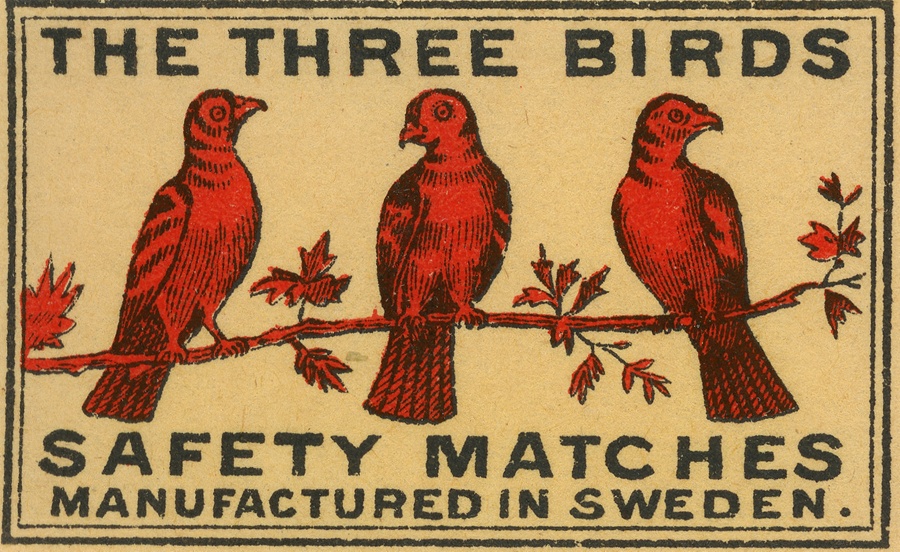

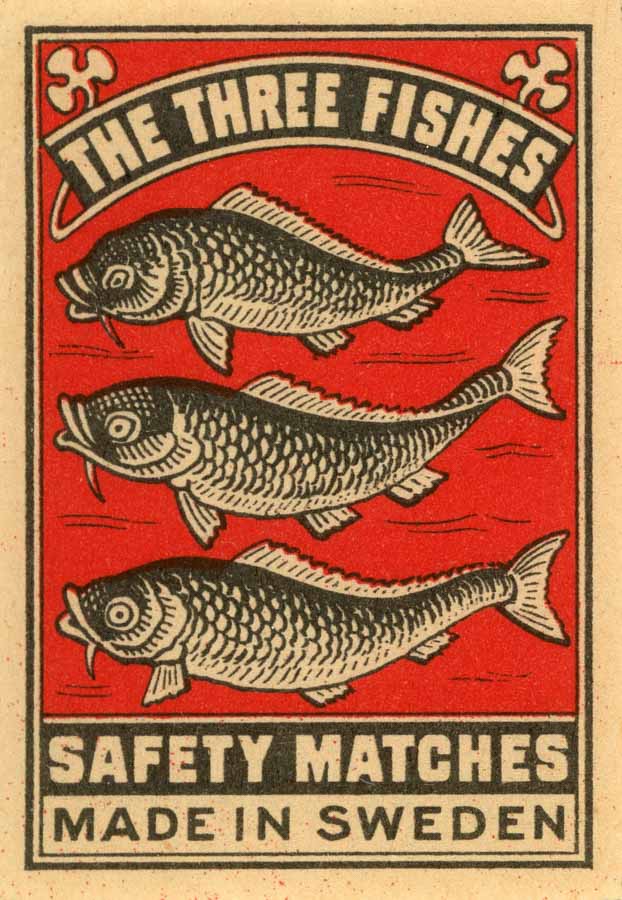

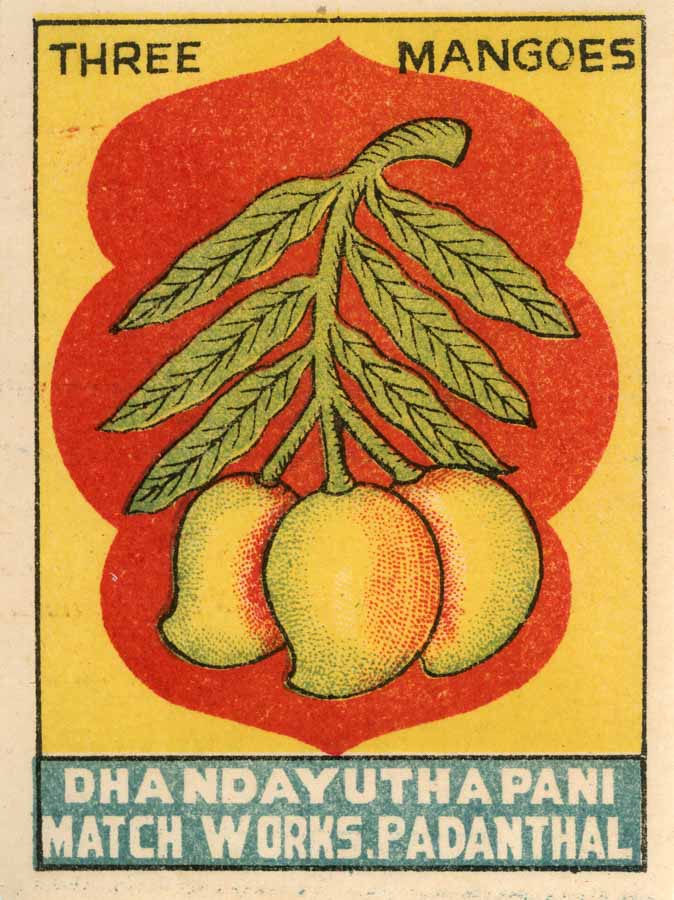

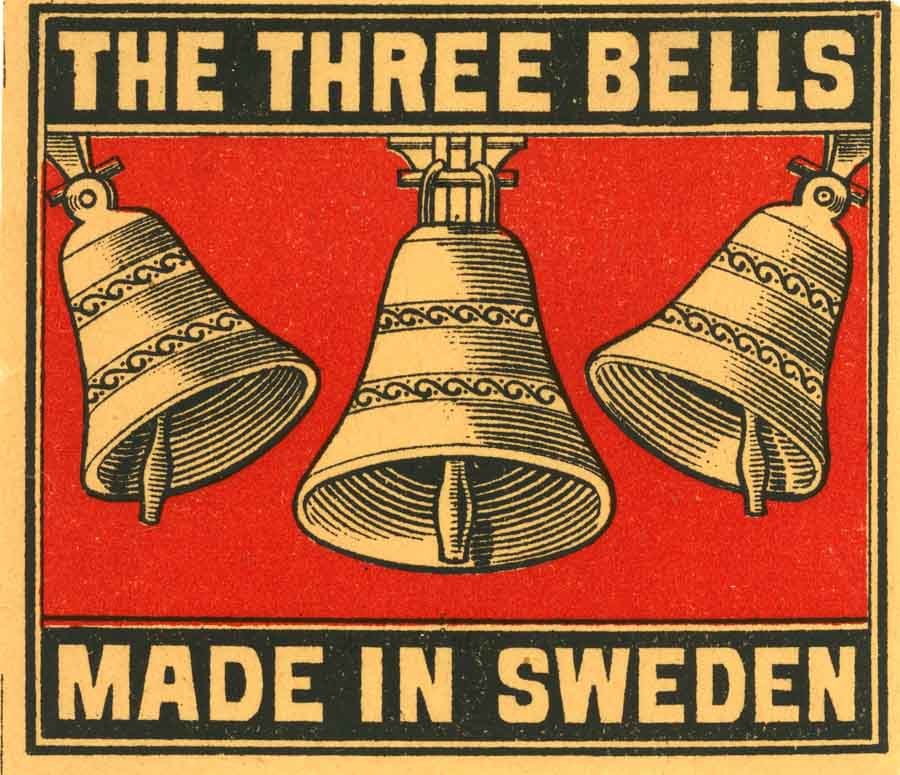

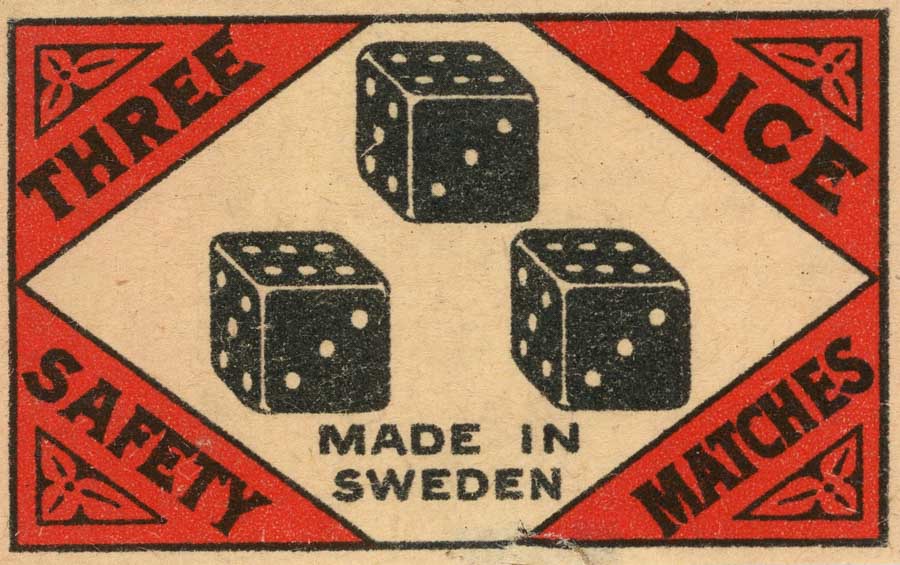

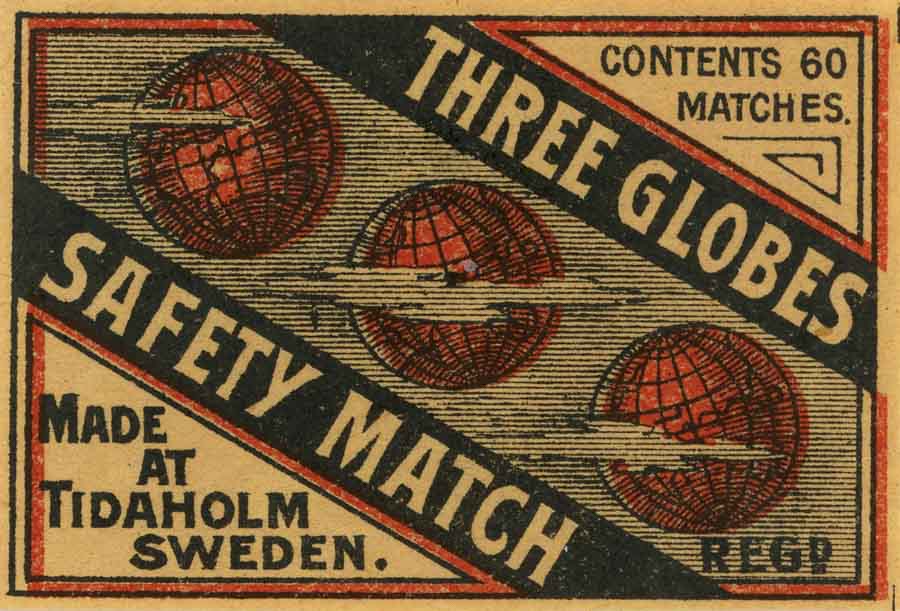

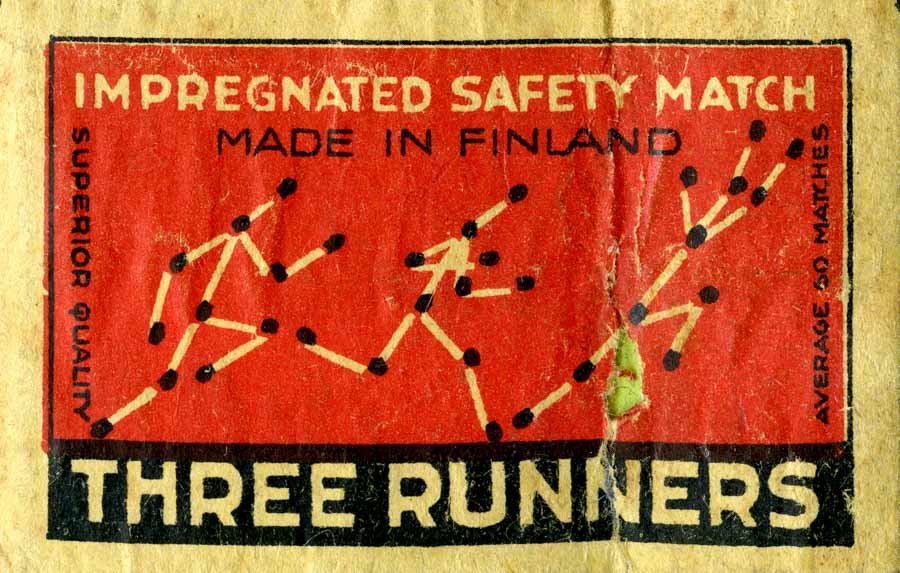

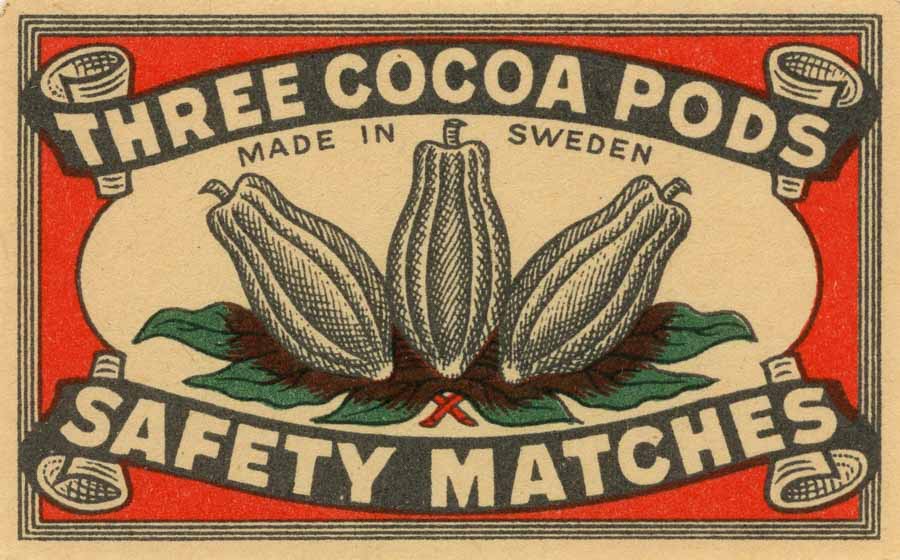

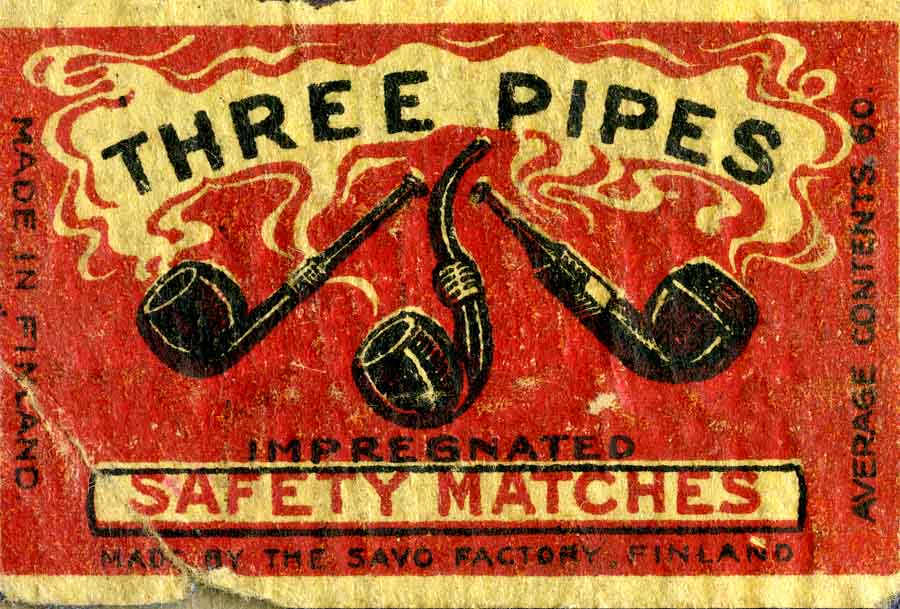

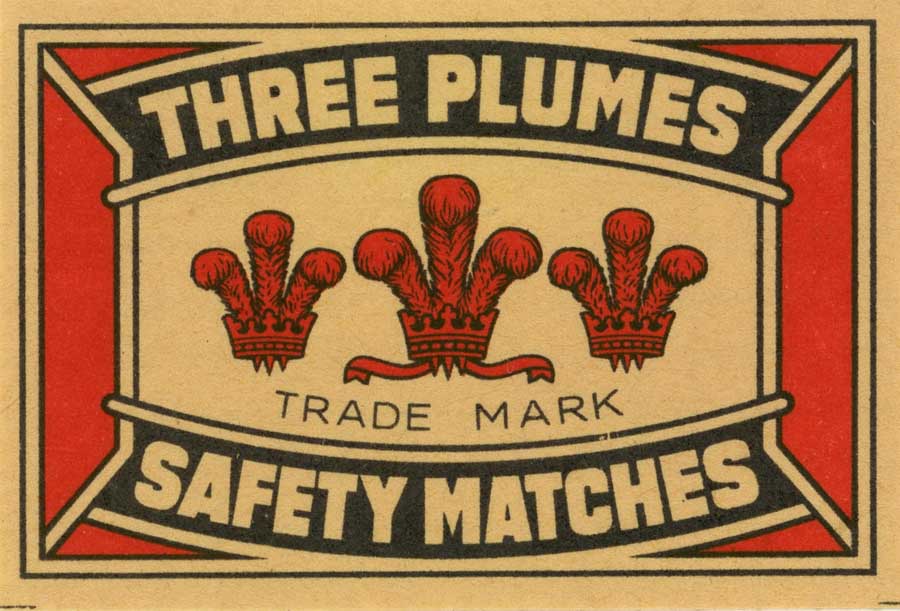

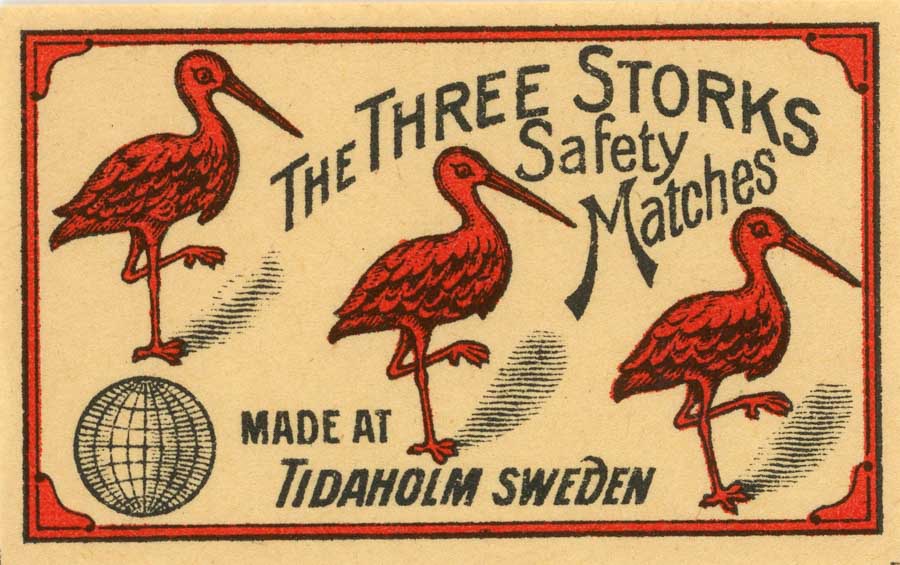

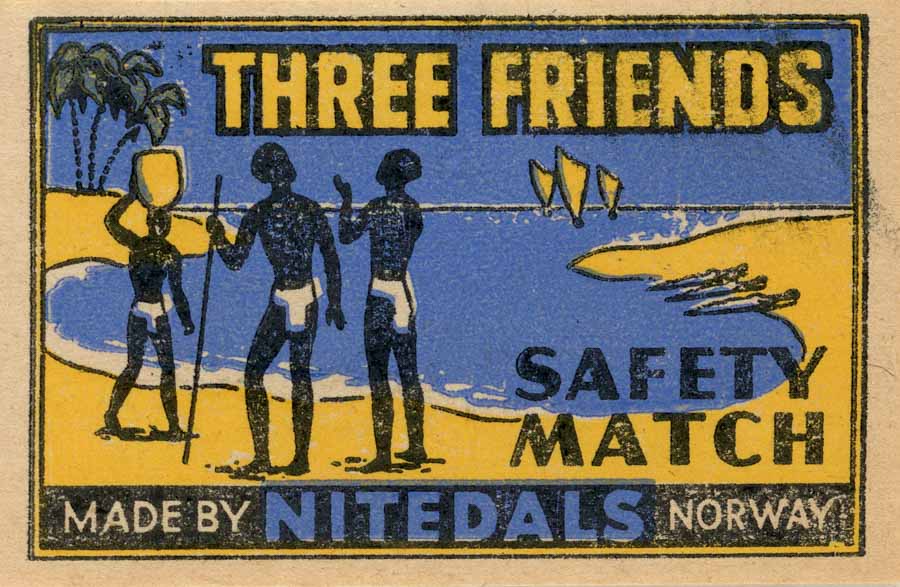

What is it with matches and the number three?

Always a sucker for brightly coloured bits of paper, I’ve managed to accumulate a small collection of matchbox labels. I like these odd little works of art that flourished for years in a seemingly unlikely niche. They are like postage stamps, I suppose, in that they had strictly utilitarian beginnings but soon became a field for fertile design imaginations. I’m often baffled as to why certain designs were chosen to decorate the outsides of matchboxes, and some are nothing short of weird.

But one of my earliest, most enduring and still unanswered queries is, why do so many designs involve the number three?

True, you will find other numbers, and plenty of designs with no numerical reference whatever. But take my word for it, there are lots of threes on matchbox labels.

If you pay attention to old matchbox labels you’ll see that lots of them come from Scandinavia – especially Sweden. There’s a good reason for that. Matches used to be dangerous little things to have around the place: tipped with toxic white phosphorus that could ignite too easily for comfort. Also, some workers involved in making phosphorous matches suffered terribly from the substance’s toxicity, falling ill with “phossy jaw” – where their teeth fell out and their jaws disintegrated.

In 1844 Swede Gistaf Erik Pasch , helped by his teacher Jons Jacob Berzelius, found that red phosphorus was a much safer bet than the white stuff, but the trick was actually getting it onto a reliable product. Pasch came up with the great idea of moving the phosphorus off the match-head and onto the striking surface, but his efforts to get a product to market eventually fizzled out. In time, however, the cost of making red phosphorous fell, and match-making was increasingly mechanised.

Johan Lundstrom and Arvid Sjoberg made a success of safety match manufacture at their factory at Jonkoping in Sweden (it’s a museum today), and from the late 1860s the product really took off. This success was helped by rising consciousness around the world of the downsides of phosphorous matches – which were ultimately banned in the 1920s.

Safety matches changed everything. Suddenly it was possible to carry in your pocket a safe and reliable means of making fire, and matchboxes became handy little mass-produced billboards for art and advertising. Lundstrom got out of the match business, but as it grew and prospered it was eventually taken over by one of the great colourful characters of Swedish capitalism, Ivar Kreuger.

Kreuger was an aggressive businessman who understood the power that monopolies bring. He invested widely in many businesses, but is most commonly remembered as “the Match King”. Krueger’s family had been in the match business for some time and when they got into trouble shortly before World War I, Ivar converted the business into a stock corporation, then steadily bought up competitors during the war years. He merged the corporation with Sweden’s biggest producer and created Swedish Match, a corporation that today still sells tobacco products – including the big-selling “snus” that so many Swedes seem addicted to.

At its peak, Kreuger’s global empire controlled almost three-quarters of world match production. And while he was clearly an extraordinary businessman, many historians have dubbed him a swindler and a fraud. For years he treated his global business as a de facto bank, lending huge sums to national governments in return for monopolies on match sales and production. His sprawling empire collapsed in the Great Depression and he was found dead in March 1932. Much debate followed as to whether he had suicided or whether somebody had murdered him. Given that he was shot in the chest in a Paris hotel room whilst on his way back to Sweden to give evidence to an inquiry into his murky and far-reaching business affairs, suicide would be my second guess. Actually, the collapse of his empire had grave implications for the Swedish economy and it took years of strained negotiations to sort out the vast mess he left behind.

Anyway, that’s why so many matchbox labels carry the “Made in Sweden” legend. And why so many matches made in other countries were ultimately owned by Swedish interests – Australia’s “Redhead” brand, for example, As to the business with the threes, I’m still in the dark. One theory relates to a superstition among soldiers that it is fatally unlucky to be the third person to light a cigarette from a single match. This superstition is said to have arisen in the Boer War when troops found that keeping a match lit long enough for three lights gave snipers a good chance to draw a bead on a victim. The superstition was certainly alive and well during World War I, during which many British soldiers would extinguish a match as quickly as possible after the second light to avoid attracting the hoodoo.

I can’t help wondering if canny match producers, knowing of this superstition, might have encouraged the use of the “three” motif as a sort of subliminal reminder. Anything to discourage excessive frugality and encourage match consumption? I turned to the definitive book about matches, Swedish Matches to Swedish Match, and found no answer: just speculation that three might have been used so often because it was considered a sacred or mystical number.