As a young circuit preacher at Murrurundi, in the Upper Hunter Valley of NSW in the 1860s – then later at Maitland, Singleton and Newcastle – the Reverend John S. Austin had his fair share of near-death experiences, witnessed a fatal traffic accident in High Street, Maitland and lost his daughter in a drowning tragedy in the Hunter River.

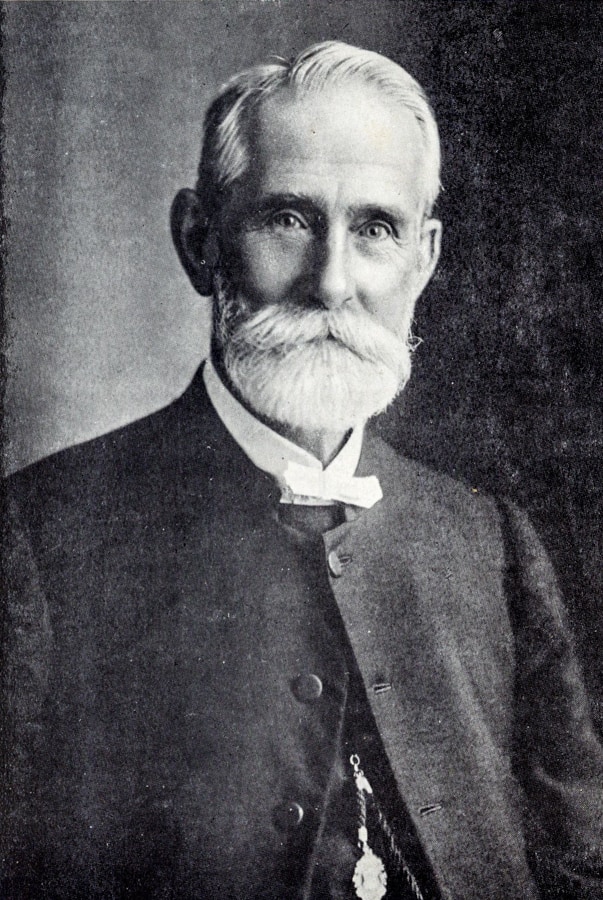

The Methodist minister John S. Austin lived into his 80s and wrote an autobiography with the unpromising title Missionary Enterprise and Home Service, a Story of Mission Life in Samoa and Circuit Work in New South Wales. Far from being as dry as it sounds, it’s a fascinating read.

Austin was born in Sydney in 1841 to staunch church parents. He seems to have been a natural for the ministry and he took up his first circuit Murrurundi in 1865.

At that time Murrurundi and Blandford had a combined population of about 1000 but Austin’s work took him much further afield than those towns. In his book he lists many place names, some familiar to modern-day Hunter residents, some not. Aberdeen, Foley’s Folly, Box Tree, Waverley, Wallabadah, Nundle, Hanging Rock and Scone are all mentioned. When he stayed in Scone Austin was invariably the guest of Chinese Methodist William Oram Chi.

His first visit to Merriwa was traumatic. He’d been wrongly told there were no Protestant services taking place there and he rode over to offer his own. It turned out that Merriwa was already well served by the Church of England and he was given the cold shoulder. He was overcharged by the publican for his night’s accommodation and although most of the townspeople he visited told him they’d come to his service, they left him in the lurch in the empty courthouse.

A five-hour limp to Doughboy Hollow

To make matters worse, the police magistrate put him on a bum steer back to Murrurundi and the young priest soon found himself leading his horse on a track so rough and stony that the animal kept stumbling on the rocks and soon “his track was marked by blood” from the horse’s cut feet. Austin found a farmhouse where he begged some food and had a rest before pushing on, still leading his now-lame horse, but found himself still on the Liverpool Plains when night fell and it started to rain. Without shelter he started to despair, but saw a fire flare ahead. It was “a couple of men camping with a drove of pigs”, sheltering under a blanket spread over a piece of wood. He wanted to share their fire, but they recommended he keep walking to a farmhouse they declared was just four miles distant.

“The night was very dark, but by shuffling my feet on the gravel I managed to keep on the track”. He eventually saw the farmhouse light ahead and made for it, “only to find myself in a field of Bathurst burrs”. By the time he knocked at the door he invited a burst of laughter from the landholder, since he was “one mass of burrs from head to foot”. He got a meal, a bed and a stable for his horse, however, and was able next day to limp to Doughboy Hollow (the 12 mile trip took him more than five hours) where the publican fed him and lent him a fresh horse. Austin never went back to Merriwa.

Horses caused the young preacher plenty of trouble. One shied at a piece of paper on the road to Blandford and galloped through a sodden field, covering Austin in mud and causing his congregation great hilarity. Another bolted into a creek with the preacher aboard.

“As he jumped into the creek one of his forefeet got jammed between some large boulders, which brought him up standing for the moment. I shot from the saddle, landing on my head on the opposite bank, and the next moment I saw my horse coming over me, and one of his hoofs just about to smash on to my upturned face. I jerked my head on one side, just in time to avert a very serious accident, and, possibly, death, I was fairly dazed with the fall but it passed off after a while and I was able to go on again.”

His horse was standing on top of the bank, waiting for him, so he climbed on and started off. Not long after, while passing through some fairly thick bush, his horse bolted again, dashing the rider against a tree and leaving him, unconscious on the ground. When he came to, his left arm was useless. He made it to a nearby farm where a cup of tea partly revived him and he remounted to head home. He galloped all the way and never drew rein until he arrived at the home of the doctor, who, unfortunately, was away for several days. Three weeks later, when he finally saw the doctor, he learnt his shoulder had been broken. By then it had already begun to knit, not quite straight, but good enough, eventually, for life to go on as before.

Sleeping in the snow at Foley’s Folly

On another occasion Austin was riding to preach around his circuit and spent the night at Foley’s Folly where the owner of the house where he stayed warned there would be snow before morning. He was sleeping on the sofa with a good fire burning, but woke before morning “with something cold falling on my face; it was a lump of snow that had blown under the eaves.”

“I was scarcely awake when down came some more. I did not care to get up and shift my quarters, for it was bitterly cold, so I brushed the snow away and covered my head with the bedclothes and went to sleep again. In the morning the hills and valley were covered with snow several inches deep, and the branches of the trees were breaking down with the weight of it. It was a glorious sight, but I soon had more than I wanted of it, for on taking my horse out of the stable he was so alarmed at the whiteness all around him that he broke away from me and started on the track for home.”

The hapless preacher had to scramble up a difficult hill to get ahead of the horse and lead him back for breakfast. Riding in snow proved a nuisance, with the snow hardening “into balls like ice in the horse’s hoofs so that he cannot go on, and again and again I had to get off and knock it out”. He finally made it to Bowling Alley Point to preach, but hardly got a congregation, so never repeated the effort.

Austin was chosen by the church to go to Samoa and was recalled to Sydney where he married teacher Jane Barry before the couple shipped out to the islands. After years in the Pacific the couple returned to Australia. In 1872 Austin’s wife Jane died of “dropsy”, leaving Austin a widower with four children. Two years later he married again, to the much younger Sarah Ward, and it was back to the islands for another spell of missionary work.

The Austins were transferred to Maitland in 1880. The most striking incident Austin describes during his time in Maitland is a traffic accident: a collision between two horsedrawn vehicles which resulted in a woman’s death. It was in High Street, West Maitland, and Austin had just walked passed a buggy, standing outside a store with a woman and baby aboard.

“I had only gone a few yards when I started to cross to the other side. Suddenly I heard a shout, and then the sound of a galloping horse. I bounded to one side, and the horse and buggy, with the lady in it, dashed past me; if I had been a moment later it would have been over me. The horse was going at a furious pace, and before anyone could attempt to stop it, the buggy came into collision with a heavy dray, and as it did so the poor woman, with the baby in her arms, shot into the air and came down on her head in the middle of the road and there she lay, clasping her child to her breast. I ran up as quickly as I could, but by the time I got there someone had taken the child from her and two men had picked her up.”

The woman lingered some days but died. The baby was unhurt. Blame for the horse bolting fell on young boys with catapults. “They were all the rage among the boys at that time and it was hardly safe to go along the street,” Austin wrote.

Double drowning tragedy at Singleton

The Austins moved to Singleton, where they were to spend three years and experience great tragedy. On Saturday, December 20, 1881, their third daughter Annie, 15, went picnicking by the Hunter River with her friends Amy Grainger, Olive Glasson and Eliza Molster. After lunching at the river three of the girls decide to wade into the water. None of them could swim.

“The water was very shallow where they entered the river, and for some little time they simply paddled, then, joining hands, they went into deeper water so as to bathe, but they had only gone a few yards when they fell into a hole about eight feet deep.”

Their companion on the bank, Miss Molster, screamed and a young lad ran to the spot but by then only Miss Glasson could be seen. He rescued her, but the other girls had sunk to the bottom of the river and he couldn’t reach them. Nor could others who came after him until about half an hour later. Austin was away from his home at the time with two of his elder children so his wife received the bad news by herself. A rider took the news to Austin at Goorangala and he set out for home in the dark. On the way the wheel of the buggy in which they were travelling hit a stump, breaking the harness and stopping the buggy dead while the horses kept moving forward. The buggy driver was dragged along the ground behind the horses for some distance but was luckily unhurt. A nearby property owner lent the group a spring cart to finish the journey. They arrived home at 1am.

The funeral of Annie Austin and Amy Grainger was said to have been the biggest in Singleton to that time. Another blow struck the family shortly after. On January 16 Mrs Austin gave birth to a baby which appeared to be healthy and well. But on February 6, returning from a conference Austin received the message: “Baby is gone”. A sudden illness had taken its life.

Austin wrote that these calamities took a terrible toll on his wife’s health and his own. The hectic pace of church life barely slowed down in the years ahead, however, with the Austins moving wherever they were sent, mostly in NSW. In 1899 they came to Newcastle for a time, where their lives were relatively uneventful. Mrs Austin died in 1906 and is buried at Sydney’s Waverley cemetery.

I don’t know when the Reverend Austin died, but he was past 80 when he published his memoir.