Passchendaele was a word I grew up with because that was where my grandmother’s favourite brother died.

My grandmother’s been gone from this world herself now for more than 50 years, but I can see her plainly in my mind’s eye, sitting in her rocking chair in her little fibro housing commission cottage at Glendale, Newcastle, NSW.

She didn’t talk much to adults about Uncle Jack; maybe because she got more than a bit misty when she thought about him. But she told me, when I was a child at her knee, and she let me pore over the fading letters she treasured as souvenirs of his life. The baby girl in a big family, Lily Jane Allsopp – my Nanna – adored her brother Jack. He signed up, aged 27, in mid-1916, voluntarily taking the first step in a short journey that was to culminate in a fatal walk-on part in one of the First World War’s most dreadful battles. He had been a farm-labourer before he signed up, working near Tamworth.

Looking back through the telescope of her memory, Nanna could see the day Jack stepped out of her life. He was dressed and packed, ready to go off to camp. As Lily remembered it years later, he sent her down to the shop near their home in Pound St, Grafton, to buy him a jar of Vaseline. She ran all the way there and all the way back, but all she saw when she arrived – breathless at the gate, was a car driving out of the street. Maybe she saw him wave.

That was it. For the next year-and-a-bit there were cards and letters. There was a mass-produced note from the King of England, thanking Jack for his “splendid services characterised by unsurpassed devotion and courage”. Jack’s letters were full of mundane chat about mates met in England and elsewhere and the pressing need for money and socks.

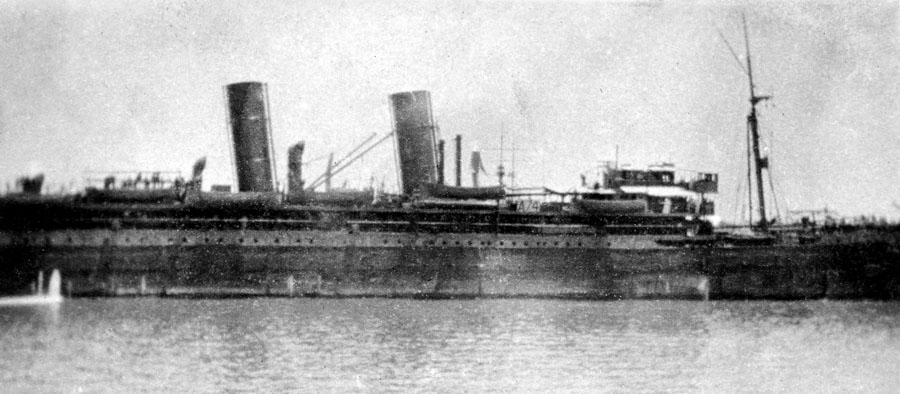

A lady in Western Australia found a note in a bottle Jack threw overboard on his birthday from his troopship, the Marathon. She observed, with detached sadness in a letter to Jack’s family, that ‘it is very hard for mothers to see their sons enlist to fight, particularly when many would not return.

“My youngest sister’s husbourne has gone and left her with 4 children under six but hers is not the worst case by a long way,” this lady wrote.

Months passed and 1917 was well-advanced. On October 8 Jack wrote from France, asking his mother for money to cover his overdraft and remarking on his “eight lovely days in London”. The rest of the letter chillingly foreshadows Jack’s fate: “Well dear I have to go through another big battle very shortly and this will be my last letter to you before entering in. So cheer up dear, if I don’t come through I shall wait for you for a little while”.

This is the only one of Jack’s surviving letters to be signed with a kiss. Nine kisses, in fact, somehow underscoring the cold feeling of fear in the earlier words. Enclosed with the letter was a photo of Jack with his English girlfriend, Ada. Visible on his shoulder is the patch identifying him as a stretcher-bearer. Taken so shortly before his death, I fancy I can seen in the photo some haunting sense of premonition on both faces.

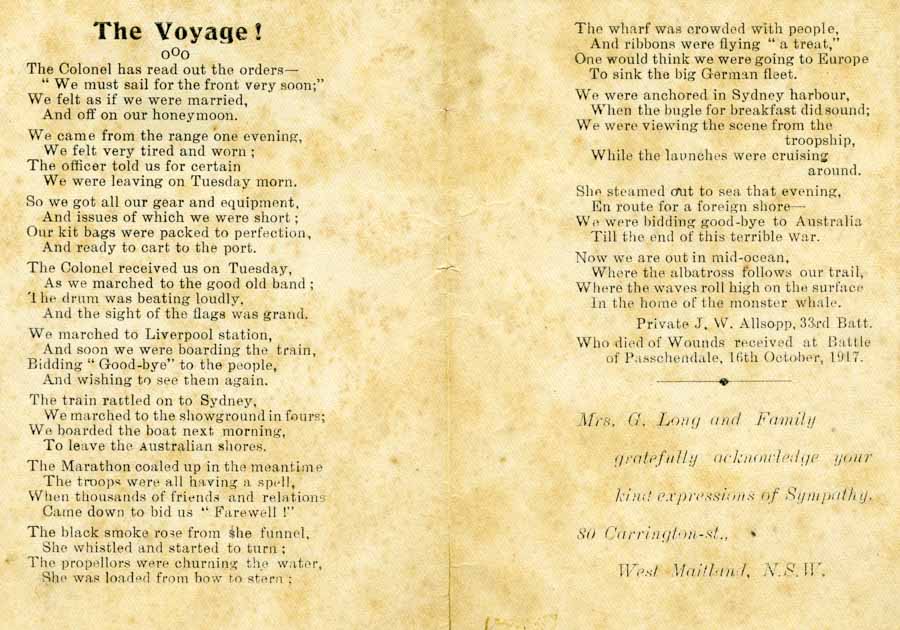

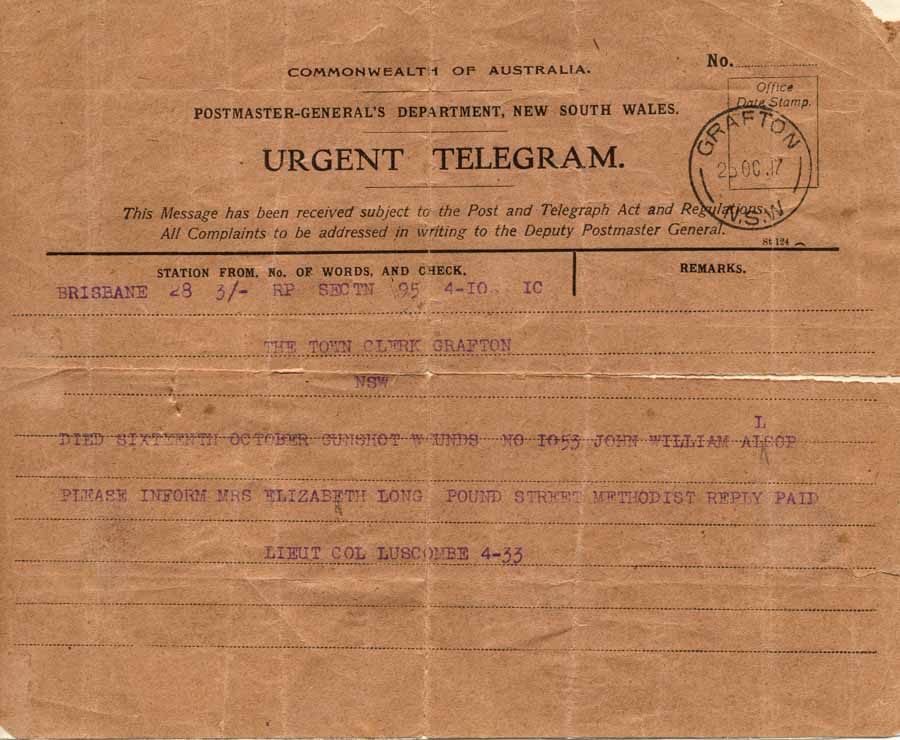

Six days later a brief note arrived, written in pencil by a Red Cross nurse who took dictation from wounded soldiers. “I am wounded but am doing all right. You will hear later how I get on.” Twelve days later, as my Nanna recalled, she was playing in the yard at Maitland. Inside, in the kitchen, a chicken was roasting. An urgent telegram arrived. Here is what it said: ‘Died sixteenth October gunshot wounds no. 1053 John William Allsopp.’

Nanna told me her mother and sisters sat on the front step and wept. In the oven the chicken was burning. Decades later she could still smell that chicken burning.

All over Australia – and indeed, the British Commonwealth – around that time families were being reduced to tears as the British counted the cost of the third battle of Ypres, known as Passchendaele (pronounced Pashen-dale). My history book tells me there were 245,000 casualties of that battle, which raged between July and November 1917. Somewhere I have read that the massive artillery bombardment that turned the erstwhile fields and woods into a sodden death-trap of deep liquid mud represented the loudest man-made noise heard on Earth to that point.

Men went into battle on wooden duckboards laid over the mud. They went heavily laden with days’ worth of equipment because resupply was impossible in the conditions. It has been said that as many people drowned in the mud as were killed by bullets and shrapnel. The following is a description of part of an advance, written after the war by an anonymous private: “The first ‘ripple’ was blotted out. The dead and wounded were piled on each other’s backs, and the second wave, coming up behind and being compelled to cluster like a flock of sheep, were knocked over in their tracks and Jay in heaving mounds. The wounded tried to mark their places, so as to be found by stretcher-bearers, by sticking their bayonets into the ground, thus leaving their rifles upright with the butts pointing at the sky. There was a forest of rifles until they were uprooted by shell-bursts or knocked down by bullets like so many skittles.”

Stretcher-bearers suffered extremely high casualty rates at Passchendaele.

“Getting killed in heaps”

Commenting on the post-war observation of a historian that the troops at Passchendaele “seemed to find some difficulty in getting forward”, this anonymous soldier wrote: “The difficulty consisted mainly of being killed in heaps.”

Nanna’s favourite brother, Jack, was in one of those heaps. Himself a stretcher-bearer, he was wounded in the back and admitted to No.5 General Hospital, Rouen, in a partly paralysed condition.

According to the sister in charge of Ward 8: “From the first there was no chance of his recovery … There was very little that could be done for him, beyond making him as comfortable as we could, and all that was possible was done. I am afraid there is little more to tell you. He did not send any special message – was too tired and ill to be questioned, beyond being asked for your address. We had many Australians in at about that time, so conclude that Pte Allsopp’s injuries were received in that magnificent advance which they had just made in Flanders.”

Jack was immortalised, in a small way, by the great Australian writer Ion Idriess, who mentioned him in his book Lightning Ridge. Idriess and Great Uncle Jack were childhood friends in Tamworth between 1897 and 1901, before Idriess moved with his family to Broken Hill.

“It nearly broke my heart to part with Johnny Allsopp,” Idriess wrote. “Johnny was my mate. Alas, I was never to see Johnny again. He was killed in France.”

A photo of Jack’s grave in 1917, sent to his family by the authorities.

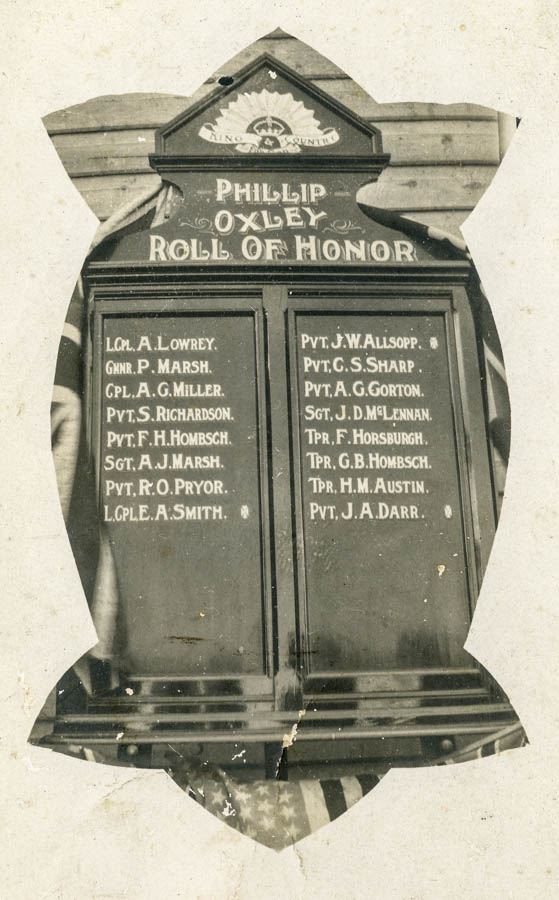

Jack’s name on a roll of honour

Ribbon given to Jack’s mother

The “death penny” given by the government to Jack’s family. Courtesy of Lionel Roser, via Alison Waugh.