Industrial and commercial newsletters and in-house publications are a rich source of fascinating historical material, often of a type that can’t be found anywhere else. One of my favourite Australian business journals is Bank Notes, the journal of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. I pick up copies and bound volumes from time to time, mostly from the 1920s and 1930s, and love to comb through them for great old photos and articles about many aspects of Australian life. Mostly the articles are written by bank staff members, and the photos come from many sources.

Among the many articles I have found in Bank Notes are some by John Henry, who in 1929 was the bank’s “Industrial Purpose Accounts Officer” in Newcastle. Mr Henry made it his business to visit some of Newcastle’s bigger industrial plants and he wrote some accounts of his visits. Here follows his description of his visit to the Walsh Island Dockyard in April 1929:

A great industry

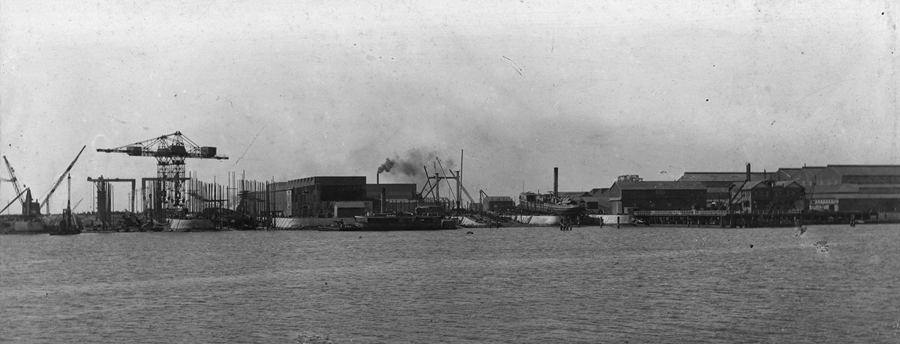

About two miles from Newcastle immediately opposite the Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s steelworks and at the junction of two arms of the Hunter River is situated the Walsh Island dockyard and engineering works where the floating dock considered so vital to the efficiency of Newcastle as a port is under course of construction.

Naturally one interested in the great industries of the Commonwealth and particularly in the State of New South Wales is anxious to obtain first-hand knowledge of these modern workshops. He thereupon embarks upon a launch provided by the management, always keen to offer every facility to the interested visitor, and after a 20 minutes trip arrives at Walsh Island. Passing up the harbour he obtains a closer view of the coal loading appliances and railway arrangements for the handling of large numbers of trucks from the numerous collieries whose product finds an outlet at the Port of Newcastle.

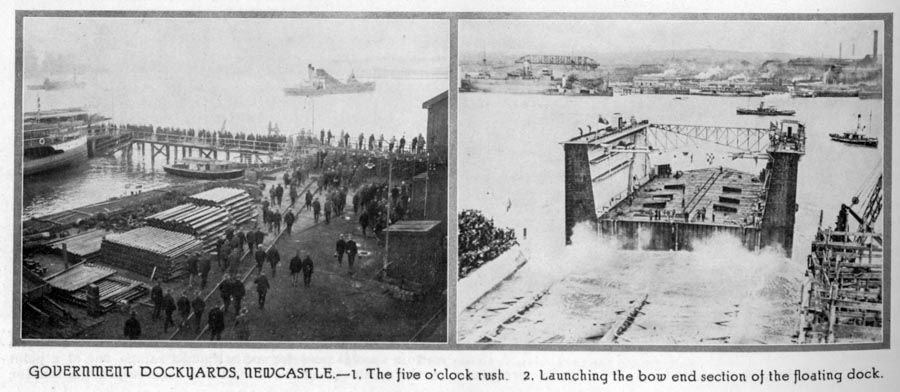

From the landing Wharf the visitor passes through the muster station and learns that there is employment of something like 2500 men. It is explained to him that each man is provided with a token on which is shown his official number. On arriving at the works in the morning the employee lifts his particular token from the hook provided and deposits it on another token board in the shop where he is employed. On ceasing work at night his token is lifted from the shop token board and deposited on the muster station board. The boards are closed at 7:30 AM and not reopened until the knock-off whistle at 5:00 PM. Any tokens remaining on the first or muster station board therefore disclose on review by the chief time keeper in the morning those men who are not at work and again at night those tokens which are not in their proper place represent men who are working beyond the usual hours. This system also assures that any man arriving late or leaving early is known to the timekeepers and action is taken accordingly to adjust his wages. Passing through the muster station the visitor is received at the office and arrangements are made for a guide to take him around the works . The administrative, accounts, correspondence, estimating and drawing offices are housed in a substantial two-storey building and a separate office accommodates the paymasters, staff record section and data and output department.

A glance at the accounts section shows this office to be well equipped with up-to-date calculating machines to handle the detailed costing system in operation. The drawing office from which are issued all plans, specifications and instructions for work which is to be carried out in the various shops, has a floor space of 3300 square feet, is well lighted and equipped with all necessary instruments for duplicating, printing and photographic work. In this office many vessels – coasters, ferries, dredges, tugs and trawlers have been designed, in addition to pumping plants, pipelines, cranes and machinery of every description. Having inspected the administrative block from which emanates the manufacturing orders required to feed this large enterprise the visitor is launched on his journey through the several workshops.

At the outset attention is directed to the store in which are housed the material requirements, with the exception of steel plates and sections which are housed in a special steel stockyard adjacent to the shipyard, and one is immediately impressed with the great variety of stores necessary in such a concern, while the numerous shelves and fittings suggest the many ramifications of a shipbuilding and engineering works. Passing from the store and entering the works the visitor observes the large area covered by workshops and in answer to his natural inquiry is given a resume of the history of the establishment.

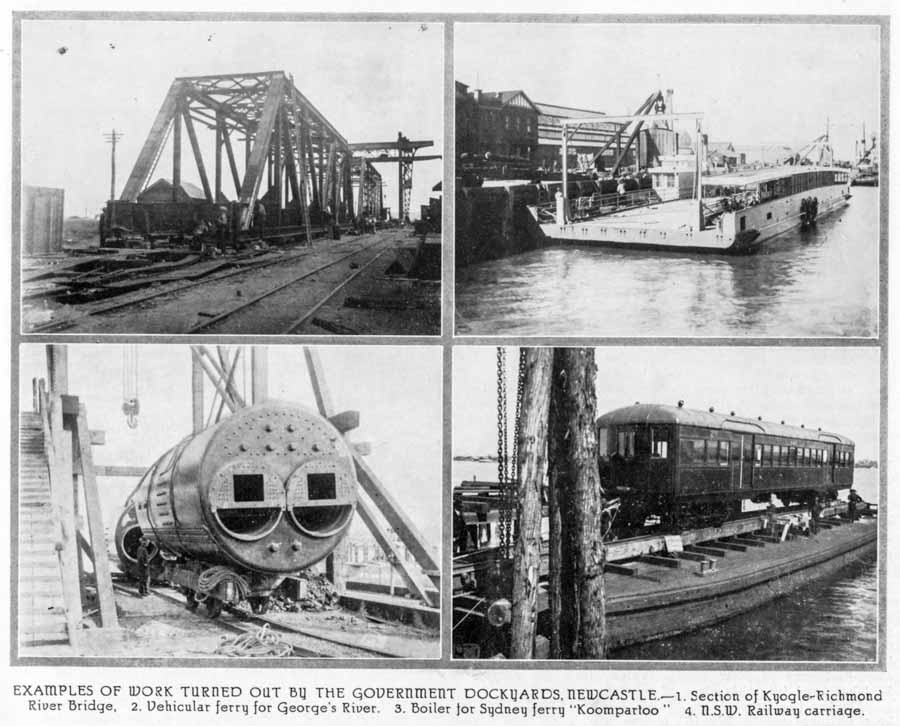

In February 1913 the Commonwealth Government took over Cockatoo Island Dockyard, where the bulk of the state repairing and construction work in iron and steel had been carried out. As a result it became necessary to find another site for a works to meet the state requirements. The foundation stone of the Walsh Island Shipbuilding and Engineering Works was laid by the Hon A. Griffiths, Minister for Public Works, on the 14th of June 1913. Construction work was pushed along rapidly from that date until at the present time. The area covered is 145 acres with a water frontage on the southern arm of the Hunter River of 2000 feet. Originally equipped for shipbuilding and ship repairing in all its branches, bridge building and general engineering, it has through slackness in the shipbuilding trade in Australia developed other outlets for its activities, adapting to other work machines specially designed for ship construction. These activities include all-steel car construction for railway work railway rolling stock, electrification work, welded steel pipelines and cast iron pipes for all services. In view of the railway carriage and rolling stock work increasing it is proposed to eventually connect up the Walsh Island works with the mainland by means of railway to the main northern and northwestern line, thus facilitating transport of material and machinery without trans-shipment to any part of Australia which has railway communication.

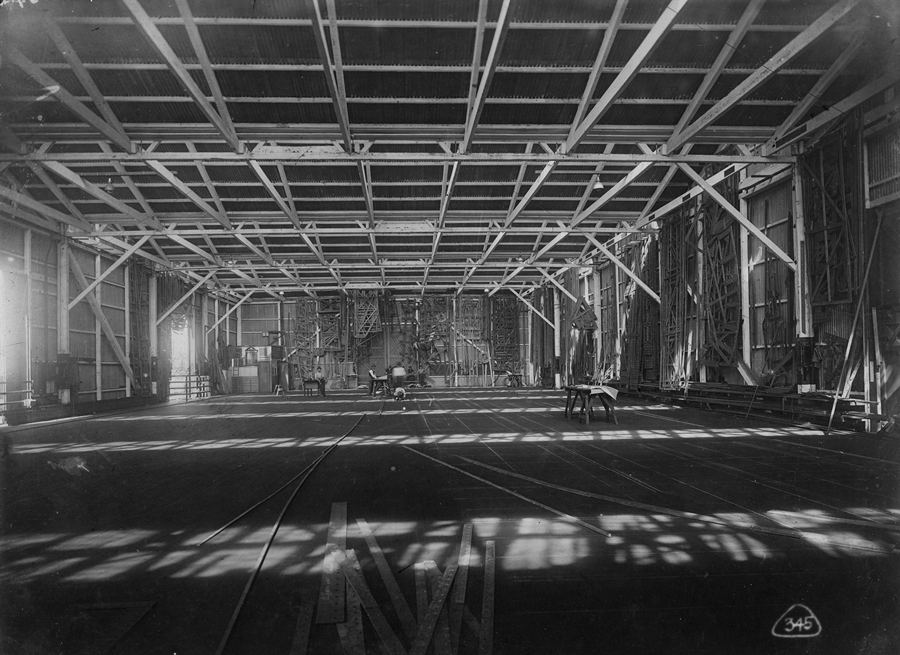

Mould loft

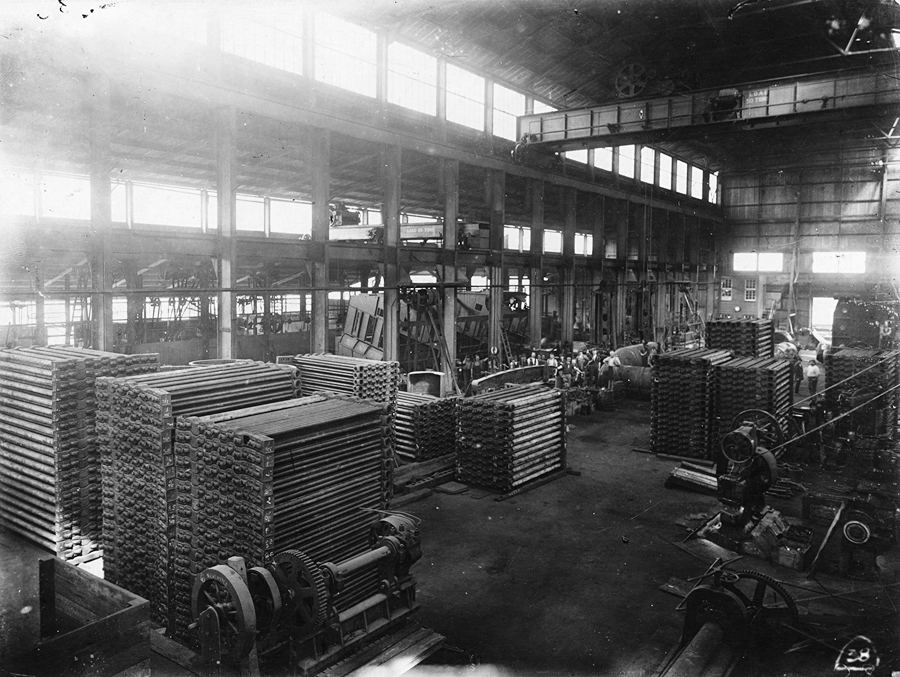

Shipyard machine shop

The works have now been equipped and developed to cope satisfactorily with any engineering requirements of the Commonwealth. What was once a mudflat has now been transformed into works with enormous capabilities. A brief survey of the departments and plants follows. The first shop visited is the mould loft in which the most intricate laying off and development work can be carried out. Here ship’s lines are laid down full size and fared, bridge sections laid off and template work of all descriptions made. This mould loft compares favourably with any overseas. After the mould loft the powerhouse is reached. For the main driving power the plant is well equipped with motor driven air compressors, hydraulic pumps, motors etc for the whole of the works at its busiest periods.

After the powerhouse, passing the paint shop, the shipyard machine shop is inspected. This shop contains up-to-date beveling machines and a frame furnace which can be extended if necessary for any length of frame desired. The bending slabs are already arranged for large vessels and in this establishment is ample space for extension in this direction. The equipment of this shop also includes a modern multiple punch. This machine, which is self-operating can handle plates 6 feet 9 inches wide and 28 feet long. Eighteen to 30 punches can be operated at one time and holes up to 3/4 inch diameter can be punched 10 at a time at a speed of 20 strokes per minute. In addition to plate work the machine has been adapted to punch angle sections, the holes in which are exactly similar to those punched in the plates. The further improvement was made when this machine was fitted with shear blades – one on either end – so that the plates when passing through the machine for punching were also sheared at the same time, thus ensuring correctly lined and punched plates. In addition to the multiple punch many other efficient modern machines are to be seen here; viz single punches, a Jacques punching table, heavy and light shearing machines, keel bending machines, rolls, nests of Asquith drills and countersinking machines – all of which are undercover to allow of continuous operations in all weather and are lighted for shift work if necessary. A large guillotine shear is capable of shearing plates 10 feet in width by half an inch thick.

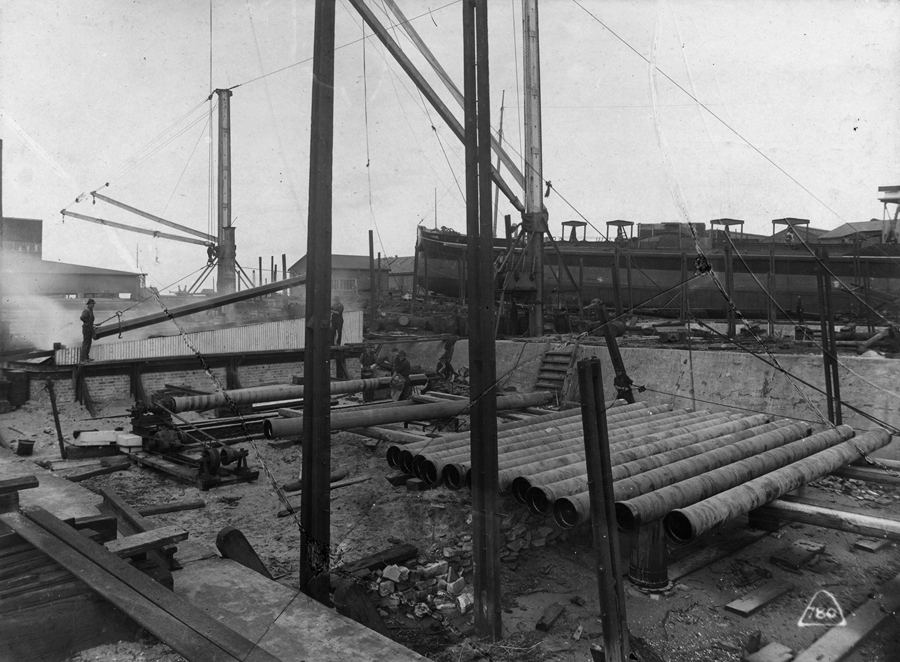

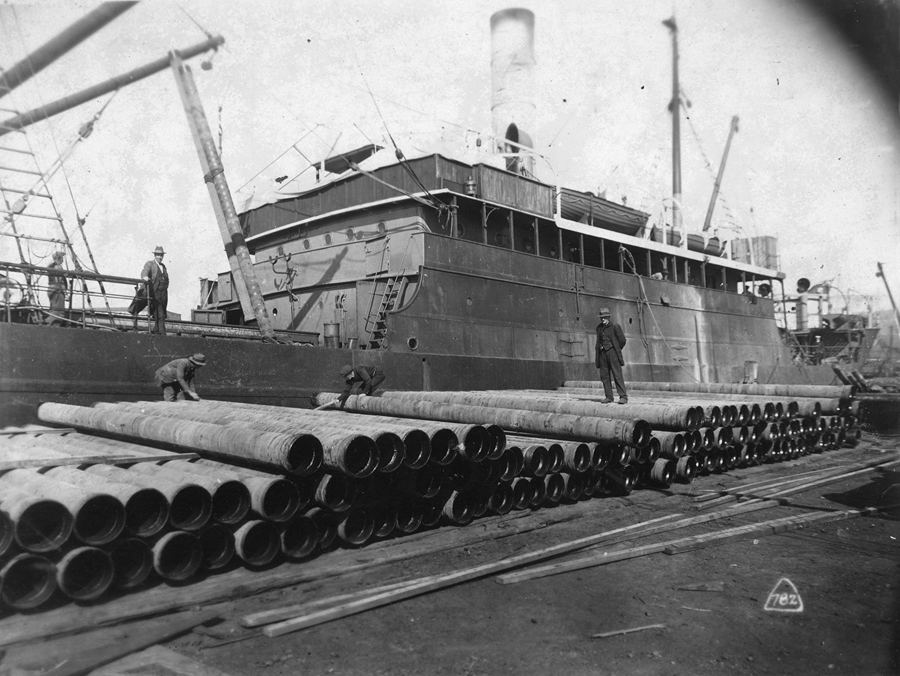

Tarring and wrapping pipes

Shipment of pipes for Melbourne

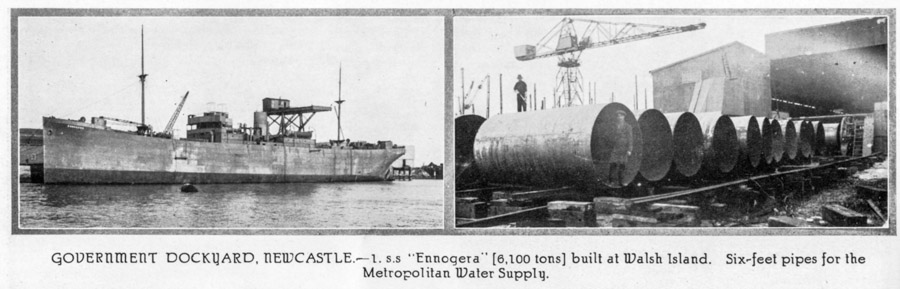

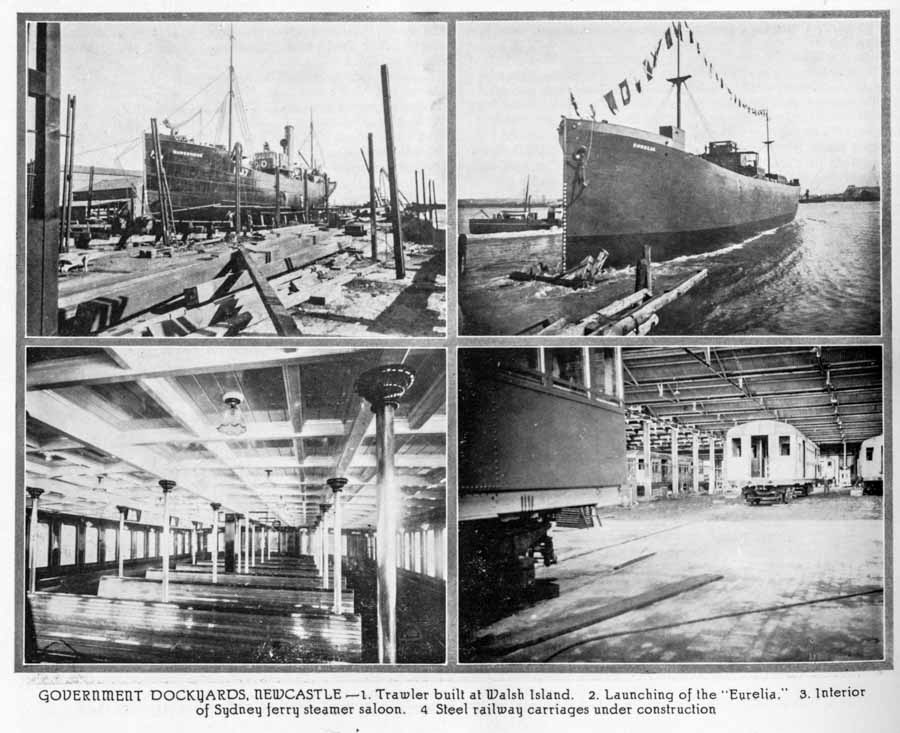

The output of this shipyard machinery has been very great and is now further reinforced by the addition of an extensive electric welding plant with a continuous supply of 4000 amps, this in close proximity to the shipyard machine shop and the building berths. Adjoining this shop is the plant for the manufacture of mild steel pipes where one mile of steel pipes can be produced in one week. There are three slipways or building berths in the shipyard on which have already been constructed vessels up to 6000 tonnes deadweight and two patent slips for ship repairs and cleaning. The ships are spanned by two four-ton Sir William Arrol’s cantilever cranes with 95 feet radius, one four-ton cantilever travelling crane designed and built at Walsh island, and are also served by two 10-ton Goliath Alliance travelling cranes. All cranes are electrically operated.

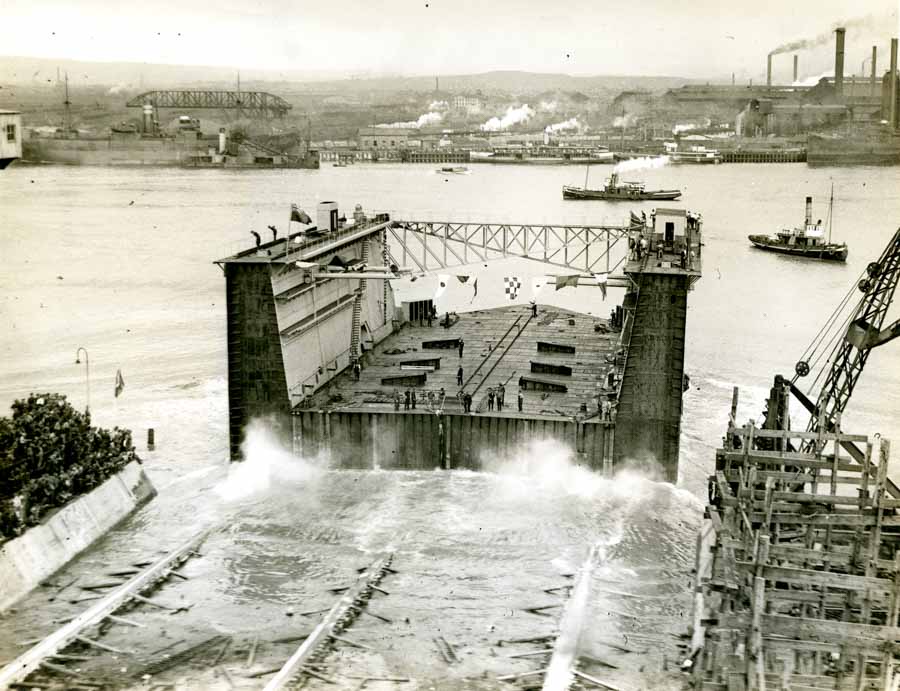

At the present time the large No. 4 slipway is occupied by the new 15,000-ton floating dock. It will be of interest to readers to note that this floating dock was subsidised as a naval work in the following manner: After unsuccessfully tendering for a 10,000-ton cruiser for the Australian Navy – for which a British firm was successful – an opportunity came for Walsh island to secure a subsidy being a portion of the amount saved by the Commonwealth Government through building the cruiser overseas. After much negotiation in which the capabilities of Walsh Island for carrying out this important work were fully determined, a subsidy of £135,000 was eventually secured. A floating dock was preferred for the Port of Newcastle on account of the uncertainty of suitable foundations for a graving dock coupled with additional risk through many old coal mines having been worked under the harbour in all directions; The shorter period required to construct a floating dock as compared with the graving dock; The facilities being in readiness at Walsh island for the construction of a steel floating dock; And finally, after the subsidy was arranged, a distinct advantage from the naval point of view by reason of its mobility. There are further incidental advantages also in favour of the floating dock.

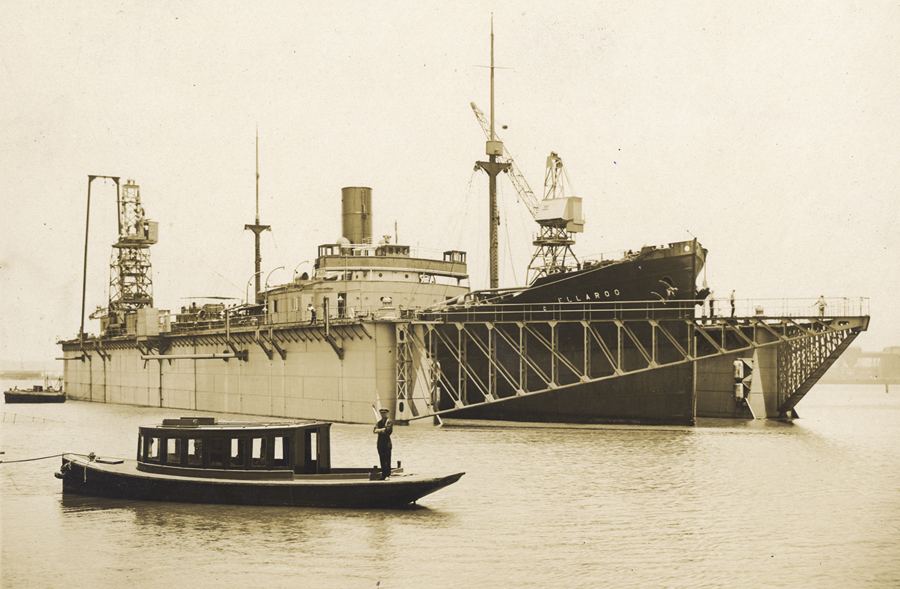

On Friday the 5th of October, 1928, the Hon T.R. Bavin KC, Premier of New South Wales, launched the centre or main section of this dock and on the 15th of March, 1929, Mrs Buttenshaw – wife of the Minister for Works and Railways, New South Wales – launched the bow end or second section. It is expected that the 3rd and last section now under construction will be completed and ready for use by September 1929. The dock has been designed to suit local conditions, coupled with Admiralty requirements in terms of the Commonwealth subsidy and as originally arranged will be in three sections of approximately equal lengths of the self-docking type – any two sections being capable of docking the third section. For the quick docking of the smaller coastal vessels the dock will be operated in two separate units, one length of 210 feet as one unit to lift 4000 tonnes and one unit of two lengths each 210 feet making a total length 420 feet to lift 11,000 tonnes. Both of these units will be self-contained, electric power being generated on the dock by diesel driven generators. When the two units are connected together the lifting capacity will be 15,000 tonnes, length 630 feet and clear width of entrance 82 feet – similar in many respects to the Singapore floating dock though it has not gained anything like the same publicity. Two sections of the dock have now been built and are being completed as the larger of the two units mentioned above.

This dock, which under naval agreement must be available for service anywhere, will be capable of being towed to sea in one length and moored in open water. Whilst at Walsh Island, however, it will be moored off the foreshore by three steel lattice booms each 126 feet long secured at the shore end to anchorages of concrete. The cost of the Walsh Island floating dock with all workshop machinery and equipment on the dock; mooring berms, anchors and cables, wharfage alongside and railway tracks thereto will be £410,000. This is inclusive of the £135,000 subsidy from the Commonwealth Government. Coming from the shipyard we pass through the bridge yard which is 1100 feet long, equipped with nests of modern drills and machines. Two 10-ton Goliath cranes run the full length of this yard in which many bridges – both of the plate girder and truss type – have been constructed, including the Katherine River bridge of the plate girder type, the Richmond to Kyogle bridges of the truss type and the Cooks River bridge of the bascule type.

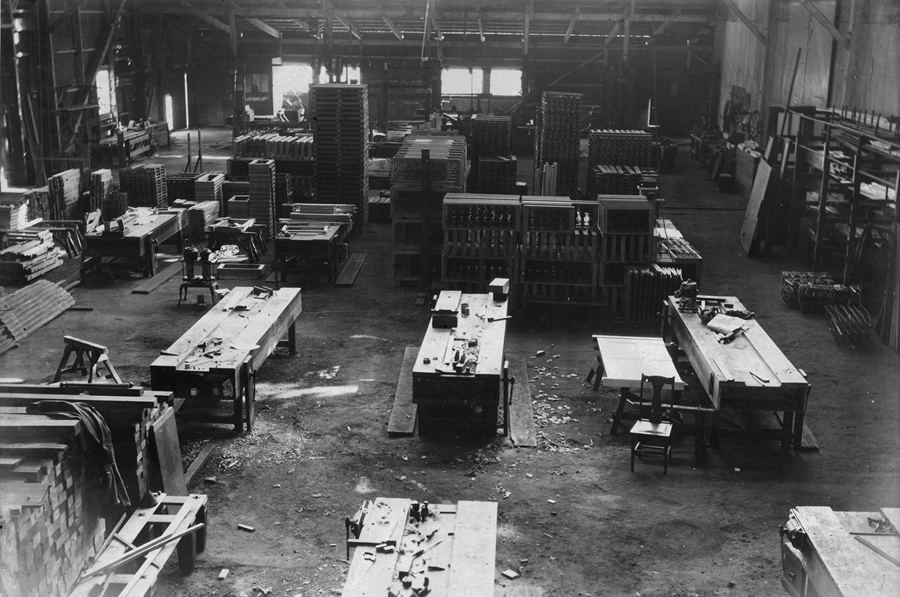

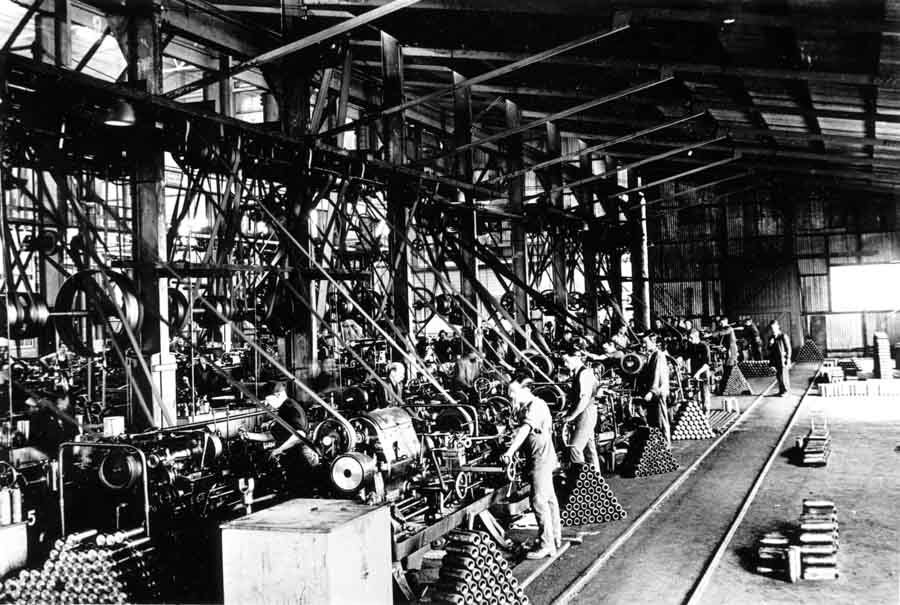

From here one passes through the pattern shop with a floorspace of 18,100 square feet and we believe that this shop is easily capable of producing patterns for the largest castings required. From the pattern shop we proceed to the foundry, already equipped for work of all descriptions, heavy and light. At the north-eastern end is the brass and aluminium foundry which has come into prominence with the all-steel carriages for the railways. At the southern end is the pipe foundry, recently remodelled and fitted with special ramming pipe cleaning and dressing machines. This pipe production has become an important branch of the works activities, the output being 200 tonnes of pipes per week. These cast iron pipes are made on the bank and also in the vertical pipe plant. The bank pipes, of three and four inches diameter and 9 feet long, are turned out at the rate of 50 to 75 tonnes per week. The vertical pipes, from 4 inches diameter up by 12 feet long, are cast in metal flasks after the pattern has been inserted in the flask. When closed the mould is rammed by machine and then dried by means of gas flares from below. The cores already prepared and dried are inserted in the mould which is enclosed and ready for the cast. This method is a quick and satisfactory operation and ensures a constant output of sound even castings at the approximate rate of 100 to 125 tonnes per week. The pipe cores are drawn and they are stored on a runway. Here they are cleaned by means of machine cleaners then ended tested and coated with tar solution as required. The blacksmith shop and forges, well equipped with steam hammers from 3cwt to 10cwt and a three-ton hammer is also available. Much important work has been turned out in this shop, its present activities being mainly the production of forgings for railway carriages and general engine work. Doubling back from this shop we enter the boiler shop, well supplied with up-to-date machines which include a large vertical plate bender, plate rolls, hydraulic riveters, shearing and punching machines and a large range of drilling machines, heavy hydraulic presses etc which completes a plant capable of building all classes of boilers. Special machines and plant have also been installed for the production of all-steel carriage parts.

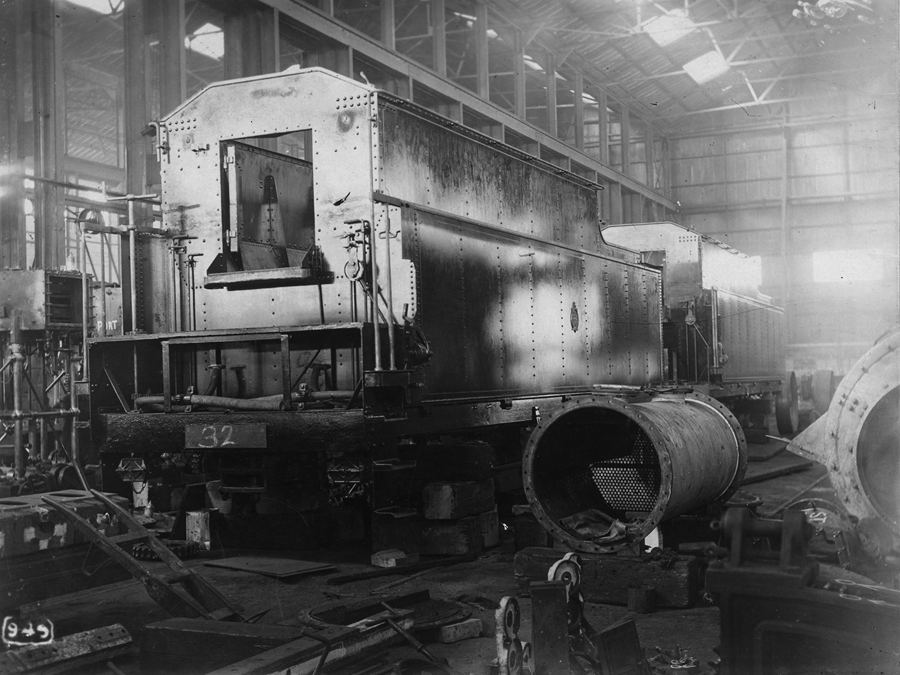

Bending rolls

Boiler shop

Rolling stock is an important production of Walsh Island and a considerable portion of the works has now been specially laid out with this end in view. A special bay of the boiler shop has been set aside for the construction of the underframes and a rail system laid out to maintain a regular transportation of the underframes on their bogies to the carriage bodybuilding shop. In this shop have been constructed Scotch, watertube, locomotive and many other types of boilers. As an addition to the excellent heavy machinery in this shop a 2000-ton press and forging machine is now being installed. We next inspect the machine shop, fully provided with machine tools of an up-to-date type. Horizontal and vertical planers with table 16 feet by 9 feet to 22 feet by 32 inches are among the larger machines, also a double-ended lathe – 30 inch throw and 47 feet between the chuck faces – and a lathe capable of turning out work up to 19 feet in diameter. At the western side of the machine shop is the assembling bay where the various parts manufactured are fitted together and the engines or machines completed. To the south of this shop and in line with the blacksmith department are the plumbers’ and coppersmiths’ shops, complete with the necessary fires and pipe bending plant, with ample space available for sheet metal work. These departments are opposite the outfitting Wharf and are centrally situated with regard to the other shops.

All-steel rail cars

Railway tender

Tramcar

Passing to the southern end of the island we come to the new railway carriage shops in which the all-steel car bodies are constructed and placed on the underframes and bogies. In the northern end of the shop are placed jigs on which the body sides, ends, roofs etc are built before being placed in position on the underframes. Further down the shop the construction and fitting of the cars is finished. Windows, seats, lights and fittings are put in and the cars are then painted ready for shipment. The carriages – the output of which equals one per day – are now transferred from the shop by a traverser and run onto a special punt for use with rail ramps – one at a point on the south end of the island, with the corresponding landing ramp on the mainland so that the cars or other rolling stock can be directly transferred to the main line for delivery to the Railway Department.

On the way back to the executive offices we visit the joiners shop. This shop is under the same roof as the loft, is fitted with the most modern woodworking machines and can undertake all classes of work including ship joinery, cabin furniture and fittings for both ships and railway carriages. The electrical and upholstery departments were also inspected. These were arranged to economically handle their particular classes of work.

Having completed an interesting and instructive inspection of these large works, inquiry elicited the fact that this important state enterprise which obtains its orders in open competition and without any preference from the government is producing profitable results to the state. Last year’s balance sheet disclosed a very handsome surplus. In other directions also its activities have been advantageous from the state point of view inasmuch as its competition has resulted in very material savings to government departments and undertakings. It would not be out of place here to refer to the very considerable reduction in the price of all-steel railway carriages to the railway commissioners of New South Wales since the entry of Walsh Island into this class of manufacture. During the Great War Walsh Island proved itself to be a national asset. Six steamers of 6000 tonnes dead-weight were built at the establishment as portion of the Commonwealth Government’s programme of building ships to replace the heavy losses in tonnage due to the submarine activities of the enemy. It is very worthy of mention the whole of the work in these ships was carried out at Walsh Island and in addition many engine parts and auxiliary machinery were supplied to other yards engaged in this class of work. The manufacture of shells was undertaken and the stage was reached when aeroplane parts, engines and propellers were turned out.

Having actually seen the work being turned out at Walsh Island and having chatted to the several officials with whom he comes in contact during his inspection the visitor cannot but be impressed with the quiet confidence which each exhibits in the success of the undertaking. From the several conversations – each dealing with a separate section of the activities – he visualises steamers carrying Australian products, numerous pipelines supplying the people of Sydney, Newcastle and other cities with indispensable water, railway carriages carrying the enormous travelling public of Sydney and suburbs, ferry steamers – passenger and vehicular – plying in Sydney Harbour, evaporator plant for the state electricity Commission of Victoria, machinery for the Bunnerong powerhouse, bridges spanning some of our largest rivers and many other important manufactures – all the product of this modern engineering plant playing a foremost part in the development of this splendid country.

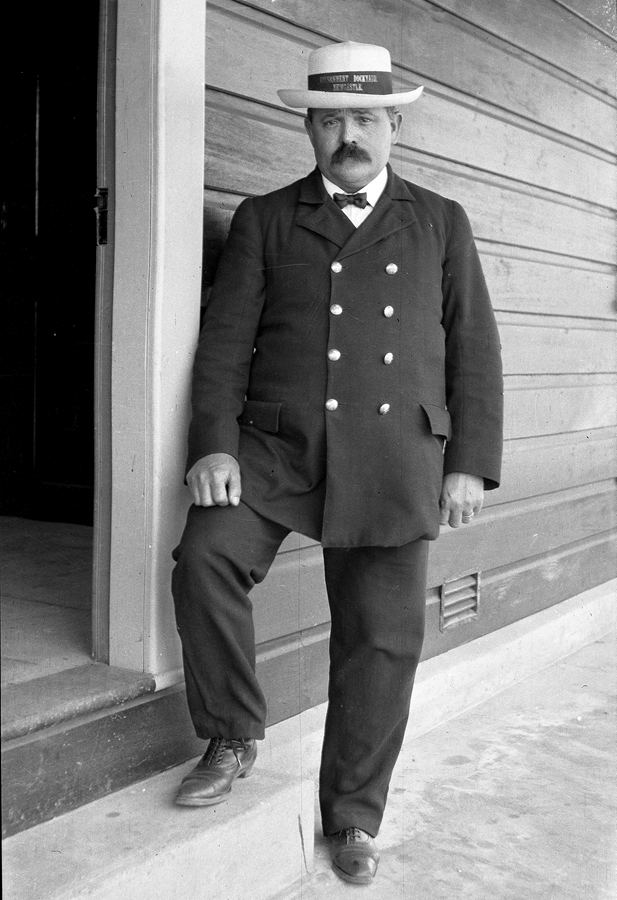

Dockyard constable

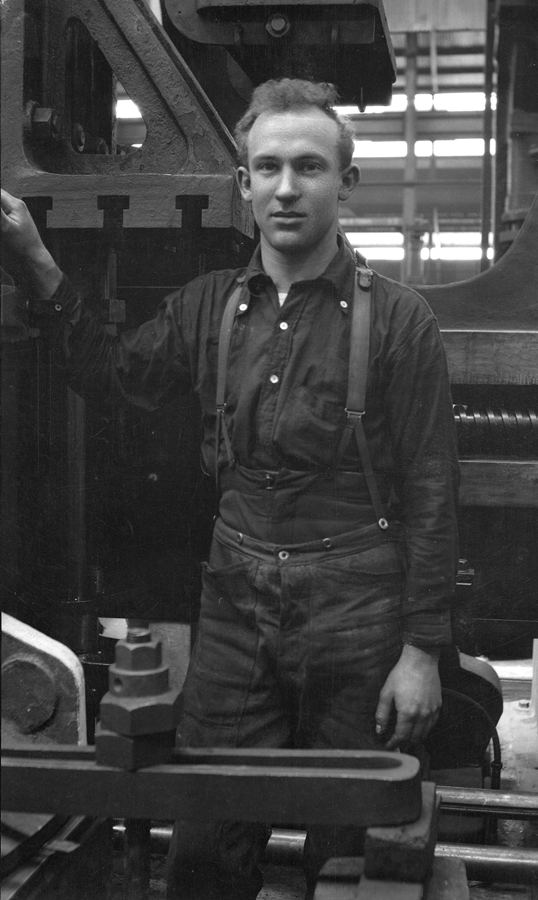

Walsh Island machinist

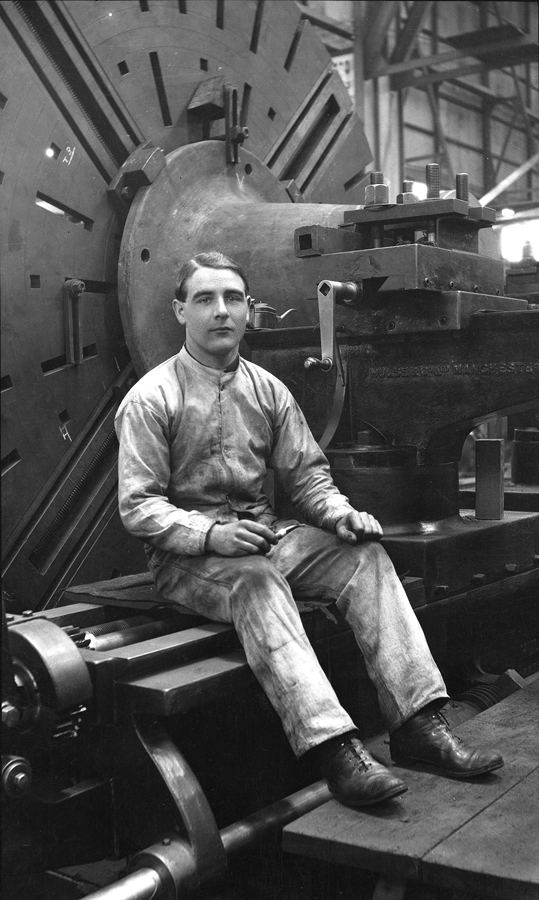

Walsh Island machinist

As he joins the throng of workmen preparing to embark on the ferry boats for their homes the visitor realises what the employment of two and a half thousand men means to the community. His mind travels to the effect of the distribution of their earnings on the business of Newcastle and he inwardly expresses the heartfelt wish that prosperity will continue to the plant and all associated with it.

Unfortunately John Henry’s good wishes were not enough to preserve this immense industrial asset. It became a political football, with conservative politicians keen to remove it from the public balance sheet. They ultimately had their way, and the plant was closed and dismantled shortly before the outbreak of World War II. Had Walsh Island still been intact at the time the war broke out it would have been a tremendous asset to Australia. Instead, the Government was forced to hastily construct a smaller and less capable version at Newcastle’s Dyke Point to deal with the pressing demands of the war.