“Oh my God, that’s my Mum!”

I was showing the general manager of The Newcastle Herald, Julie Ainsworth, a proof copy of our 2011 book, Recovered Memories, which contained many rare photographs taken around the Newcastle area during World War 2. Julie was flicking through the pages, making polite noises and nodding approval, when suddenly she spotted her mother in a picture.

“That’s my mother, Jean Dunbar, and she’s working in the Owen Gun shop at Lysaght’s in Newcastle.” Julie declared. It was a wonderful insight into a photo about which I knew little – beyond the fact it illustrated munitions manufacture in Newcastle during the war.

Julie then brought in her mother’s old photo albums which contained wonderful pictures of women workers involved in emergency drills at Lysaght’s.

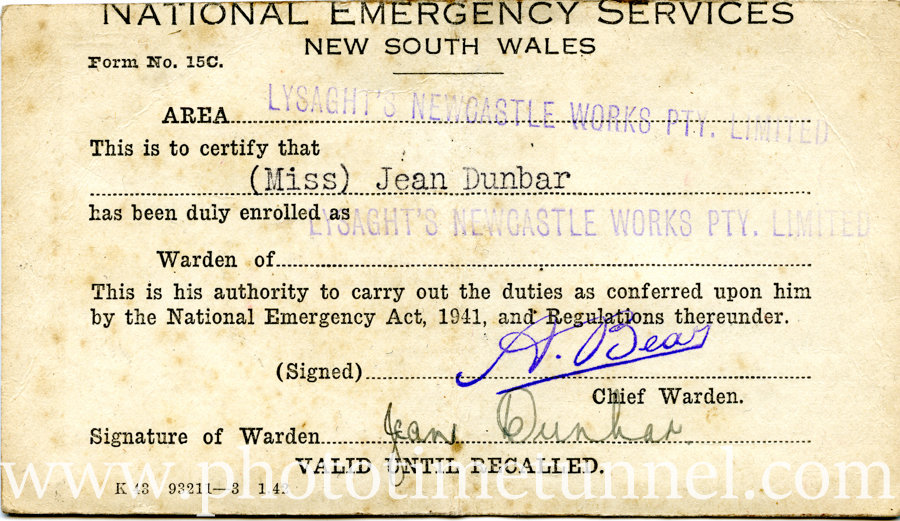

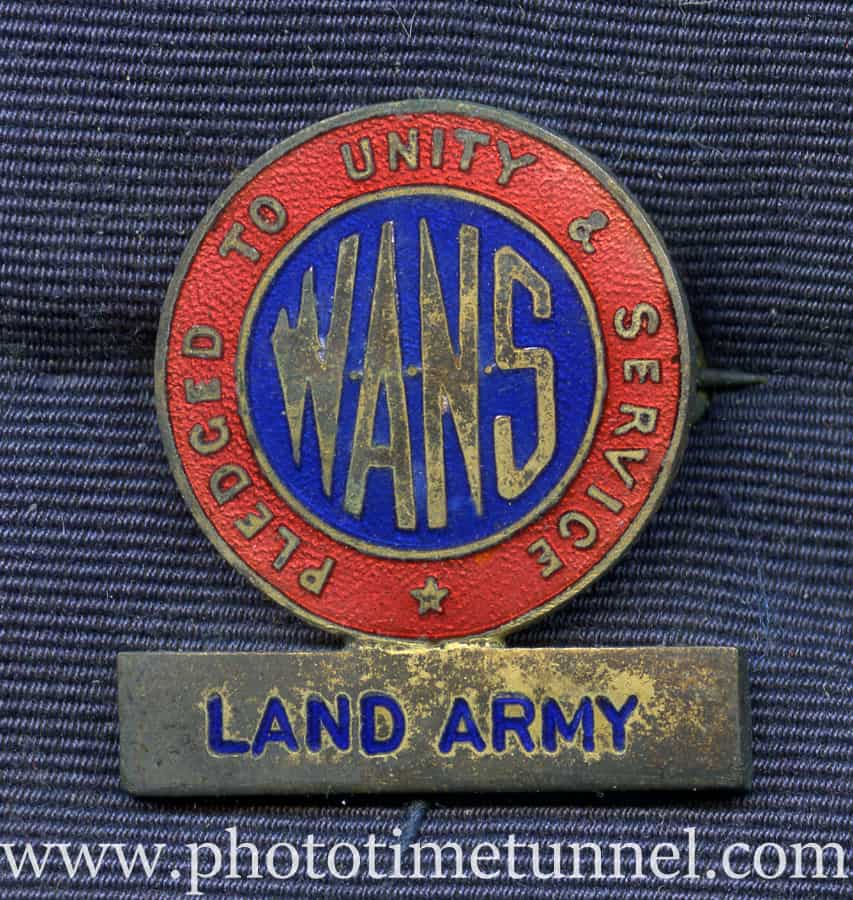

Jean Dunbar was evidently a livewire. Her father was John Jackson (JJ) Dunbar, a senior military officer who had seen service in World War 1 and commanded Australia’s 2nd Battalion for a period between the wars. Jean not only worked at Lysaght’s; she also volunteered during the war with the National Emergence Services (NES) and the Women’s Australian National Service.

Jean Dunbar

John Jackson (JJ) Dunbar

Jean Dunbar’s NES documentation

Jean Dunbar’s Lysaght’s badge

Jean Dunbar’s WANS badge

The story of the Owen Gun, which Jean and others helped build at Newcastle, is interesting. The easy-to-build, extra robust sub-machine gun was invented by a young Illawarra man, Evelyn Owen. Owen took years to perfect his creation before taking it to the Army in 1939, when he was just 23. The Army rejected it, and sent him packing.

When World War 2 broke out he enlisted in the infantry and went off to fight. According to the book Lysaght Venture, Owen put his beloved prototype gun in a sack while he was on final leave, and it was found by the general manager of Lysaght’s in Port Kembla, Vincent Wardell. Wardell looked at the gun and realised its potential value to the war effort. Young Evelyn Owen was pulled out of the infantry to supervise the mass production of the gun which, when tested, proved superior to other models in use.

A good link to information about the Owen Gun can be found here:

According to Lysaght Venture, “Mr Wardell could see the possibilities of a sub-machine gun that could be made more easily and cheaply than a standard rifle.” An annexe was built at Port Kembla and the idle space in the Newcastle Galvanised Iron Warehouse was extended and turned into a machine shop for making the gun parts. A peak production figure of 800 guns per week was reached, and 45,000 guns in all were supplied, with over half a million magazines.”

“When the Army’s requirements for Owen guns had been met, the machines and trained operators could be made available for other work, so contracts were accepted for the machining of aircraft parts. This was exacting work, mostly on small components. Even more than the Owen gun, this was a radical departure from Lysaght’s usual work, but an exceptionally high standard was reached and maintained. As with the Owen gun, much of the work was carried out by women to whom this kind of activity was entirely novel.”

Later in the war the former Owen gun shed was used to make hundreds of thousands of high-carbon steel machetes for use by troops in the jungles of the Pacific theatre of war.

The Lysaght’s National Emergency Services unit was highly regarded, winning six of the 10 Newcastle NES competitions during the war. A Volunteer Defence Corps infantry company was also formed at Lysaght’s. This was later split into an anti-aircraft and a searchlight battery.