Like a lot of people, I am fascinated by the indigenous history of the part of Australia in which I live. I’m frustrated by the paucity of teaching of this important subject in our schools, and I often wish I had better access to real knowledge about the people who lived here before us.

I have tried to read and learn, using the sources of information that are available to me. And very often, embarrassingly and frustratingly, I find that things I thought were dependable facts turn out to be not so certain, or perhaps misunderstandings, or perhaps altogether wrong.

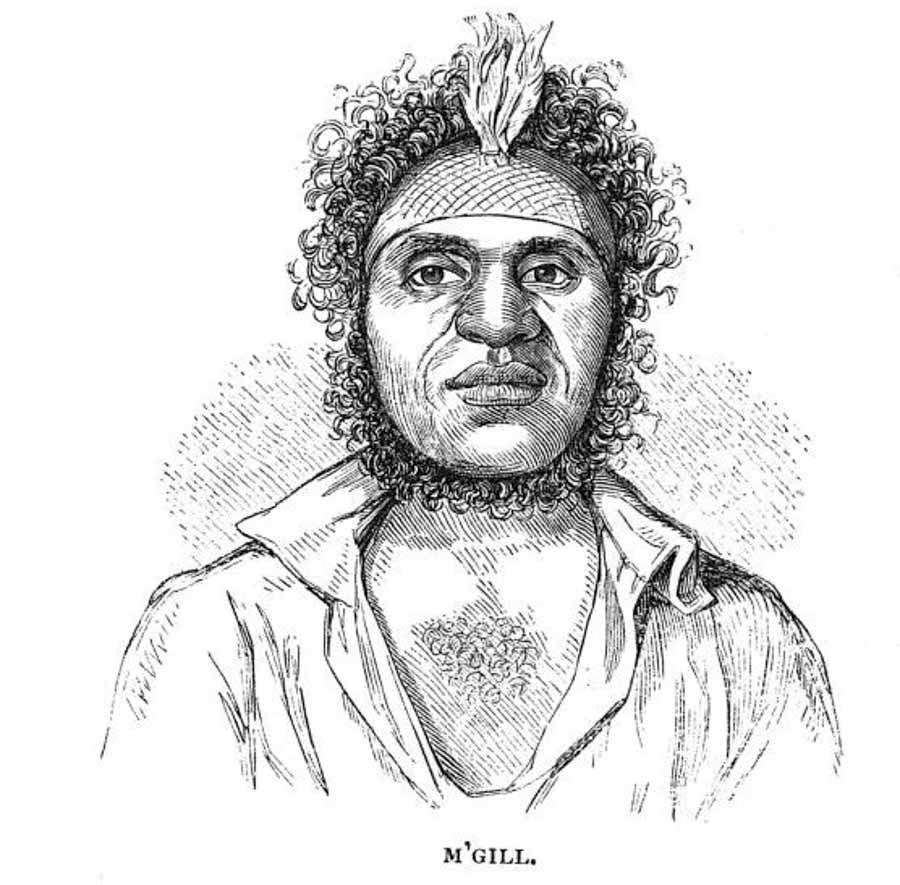

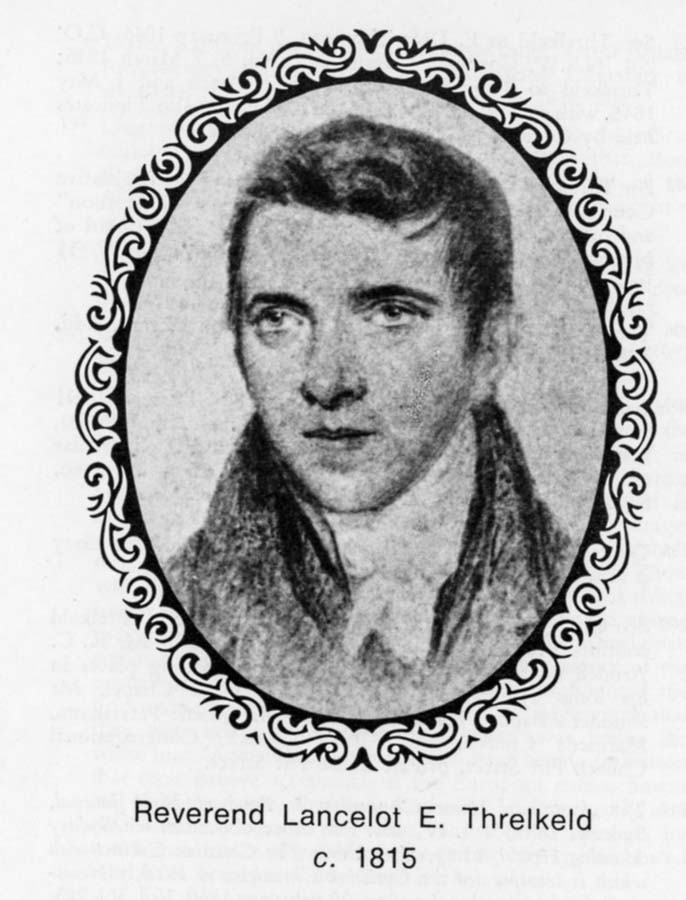

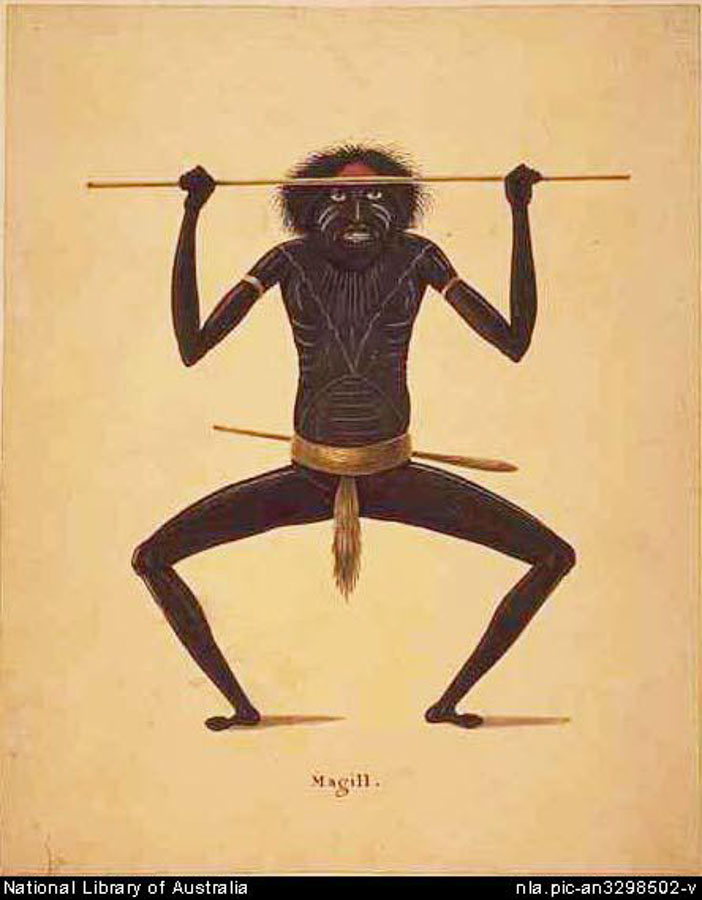

The case of the Awabakal people, for example. Obviously there were groups of people who lived, worked, hunted and played around the body of water we call Lake Macquarie, long before any white people came there. And for a long time I was certain that some of these people called themselves Awabakal. I was certain that this information came reliably from the Christian missionary Lancelot Threlkeld, who compiled a remarkable grammar of the “Awabakal” people, with the close assistance of an indigenous man named Biraban (also known as “McGill”).

It looks like I was probably wrong about much of what I thought I knew. It looks like I misunderstood some information that was already misleading to begin with. It looks like Threlkeld never said there were people who called themselves by the name “Awabakal”, which it seems was made up by a white scholar in the late 19th century. The man who made up the name had no ill intentions, I’m sure, but it’s been a confusing invention – for me, at least.

It seems fairly clear that the word “Awabakal” was invented by linguist and ethnologist John Fraser, who reprinted some of Threlkeld’s works in 1892 in a volume entitled: An Australian Language as spoken by the Awabakal, the people of Lake Macquarie (near Newcastle, New South Wales), being an account of their language, traditions and customs. In his preface, Fraser writes: “A considerable portion of this volume consists of Mr Threlkeld’s acquisitions in the dialect which I have called the Awabakal, from Awaba, the native name for Lake Macquarie – his sphere of labour.”

According to the book A Guide to the Languages of NSW and the ACT, by Jim Wafer and Amanda Lissarrague, “Threlkeld never used the name ‘Awabakal’ for the language. Horatio Hale (of the American Exploring Expedition) noted, after his visit to Threlkeld, that ‘we are not aware if [the people] have any general word by which to designate all those who speak their language. None is given by Mr Threlkeld, to whom it would doubtless have been known.'”

I am not suggesting that people stop using the word Awabakal. It is part of our language now and well-embedded. But it does seem reasonably clear that none of the groups of people who lived around Lake Macquarie before white settlement called themselves by this name.

Fraser’s edition of Threlkeld’s work certainly lists the word “Awaba” as meaning Lake Macquarie, adding that “the word means a plain surface”. Whether this usage of “Awaba” is Threlkeld’s or Fraser’s has been debated. Wafer and Lissarrague believe it is another of Fraser’s words, although I am not entirely convinced, since it is part of a list that contains anecdotes that seem to be in Threlkeld’s voice.

Threlkeld often had to travel and meet indigenous people from areas surrounding the Hunter Region, and people from other areas often passed through his mission. He observed that: “Although tribes within 100 miles do not, at the first interview, understand each other, yet I have observed that after a very short space of time they are able to converse freely.”

In evidence to a NSW Legislative Council committee in 1838, Threlkeld made these remarks about the indigenous language:

The native languages throughout New South Wales are, I feel persuaded, based upon the same origin; but I have found the dialects of various tribes differ from that of those which occupy the country around Lake Macquarie; that is to say, of those tribes occupying the limits bounded by the North Head of Port Jackson, on the south, and Hunter’s River on the north, and extending inland about sixty miles, all of which speak the same dialect. The natives of Port Stephens use a dialect a little different, but not so much as to prevent our understanding each other; but at Patricks Plains [Singleton] the difference is so great, that we cannot communicate with each other; there are blacks who speak both dialects. The dialect of the Sydney and Botany Bay natives varies in a slight degree, and in that of those further distant, the difference is such that no communication can be held between them and the blacks inhabiting the district in which I reside.

Threlkeld noted that the European colonists were, as a rule, shockingly disinterested in the indigenous languages, and on those occasions when they did show interest they often made errors through misunderstanding. One trap for non-indigenous people – which led them to imagine that people were speaking separate languages – was the number of words for specific things. “For instance, water has at least five names, and fire has more; the moon has four names, according to her phases, and the kangaroo has distinct names for either sex, or according to size or different places of haunt, so that two persons would seldom obtain the same name for a kangaroo if met wild in the woods unless every circumstance was precisely alike to both inquirers”, Threlkeld wrote.

Threlkeld described how a visitor to his mission asked Biraban the name of the native cat. Biraban replied “minnaring”, and the visitor was about to write this down as the name when Threlkeld intervened and pointed out that Biraban had simply told the visitor that he had not understood the question. On the other hand, a long-standing myth held that the word “kangaroo” really meant “I don’t know” and came into use among Europeans because Sir Joseph Banks wrote down the answer to a question he asked about this unfamiliar creature while accompanying James Cook in 1770. According to a different account, however, the word really came from North Queensland, where Banks correctly wrote down an approximation of the local word for one very specific type of this large macropod. This very specific and very regional word allegedly became, for Europeans, a blanket name for the whole species.

Another alleged example, cited in Fraser’s book, relates to whites offering bread to indigenous people, telling them it was “very good”. This led, apparently, to bread being known for some time in that area by the name “verygood”.

Given that different non-indigenous listeners would have written down the words they heard from indigenous speakers according to their own hearing and spellings, it is common to see quite differently spelled versions of the same word emerging from old diaries and word lists. This creates another class of potential confusion.

It is widely stated that the local indigenous name for the Hunter River was “Coquun”, and this may well be true. Threlkeld, however, doesn’t include this in his short list of geographical place names. He does list the word “kokoin” as a word for water, and Wafer and Lissarrague write in their handbook that a number of other Europeans wrote down the same word as a noun meaning water. The writer who stated that the word “Coquun” meant the Hunter River was J.D. Lang, but the authors suggest that “its use as a name for the river is probably a misunderstanding”.

It seems that many words that whites used in the early days of the colony of New South Wales when talking to indigenous people, and which were believed to be genuine indigenous words, were actually misinterpretations, mispronunciations or imports from completely different places which, nevertheless, were adopted by both sides for communicating with each other. “Picaninny”, for example, might be thought by some people today to be word of indigenous Australian origin. Apparently, however, it came from the West Indies, where it was a “pidgin” Portuguese term. There are numerous other examples, and Threlkeld lists a number, calling them “barbarisms”.

Clearly, this is an area that requires its would-be students to have open minds, fraught as it is with so many opportunities for misunderstanding and error. It’s extremely interesting, however, and the more I read and hear about our indigenous forebears in the country we inhabit, the more I want to know about them.