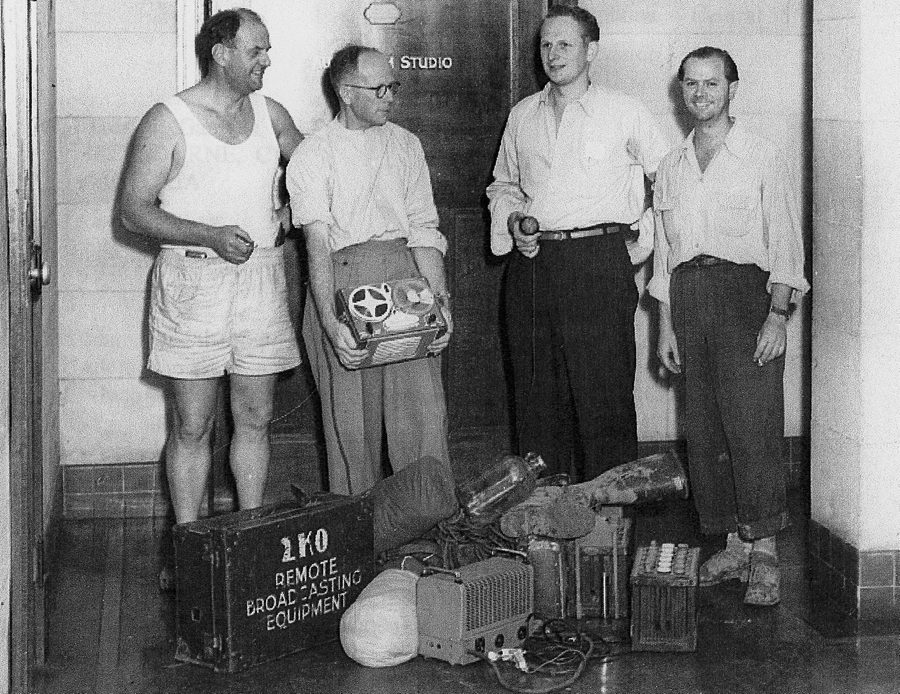

During the years I worked at The Newcastle Herald, I received many items of correspondence that I wasn’t able to use. Often this material was very interesting, but if I had no immediate use for it (given that the newspaper was both selective and demanding about content and timing) it generally went into desk-top trays before migrating into filing cabinets. When I left the paper in 2015 brought home some boxes of this material which otherwise would have been disposed of. From time to time I dip into these old files – now in my home office – and feel guilty about never having used items that were sent to me in good faith. Now I have my website I can finally put them to use. What follows is one example: a fascinating first-person account by radio engineer Max Spitzkowsky who was one of a team sent by Newcastle radio station 2KO to cover the 1955 floods as they hit Maitland. This was sent to me – years ago – by Col Spitzkowsky. I apologise for the long delay in making use of this fine material.

by Max Spitzkowsky

The following pages present a fairly factual picture of the meanderings of Ron Hurst, Harold Whyte and myself, Max Spitkowsky, as we endeavoured to supply continuity of information to radio station 2KO from the flooded districts of Maitland from Friday 25 Feb 1955 to Monday 28 Feb 1955. During this period we were the only Unit broadcasting direct from the affected area through any radio station. Conditions were rather difficult and at times I felt were a challenge to our ingenuity, which perhaps on occasion was somewhat dulled by loss of sleep, lack of regular meals, and the inability to indulge in normal personal hygiene. We worked as a team, as did many hundreds of others in this crisis. This, then, is simply the story of our small part.

Friday, February 25, 1955

On Friday 25 Feb 1955 I was called in from duty at the Newcastle Show, with instructions to be ready with the minimum of necessary equipment to leave Newcastle with Ron Hurst by army DUKW at 1pm for the flooded Maitland area. Ron and I were there, but after waiting around in the rain until 4pm we decided to check with the army at Shortland Camp, where we found that the next army vehicle would not leave before 6pm. Captain Sharpe assured us, however, that a place on it would be available for our gear and us. In the meantime we were joined by Harold Whyte complete with his personal 80 meter transmitter VK 2AHA.

At the appointed time we transferred all we had to an army landing vehicle tank (LVT). The loading ramp was then closed and we were encased in a steel prison with six foot (2m) sides and no roof – in pouring rain. Our equipment was covered with the canvas “igloo” in which we used to try to shelter from the rain at football broadcasts in winter. The next few minutes were rather hair-raising as the cumbersome LVT with engine flat-out clambered up onto the prime mover which was to take us as far as the flood water would allow. At one stage during these gyrations I feared we would go over backwards, and Harold Whyte and myself had some difficulty in keeping the accumulators and ourselves in an upright and fixed position.

Moving on to Newcastle police station, about half a ton of fresh yeast was loaded, and covered with cardboard in a rather pathetic attempt to keep it dry. Led by a police motor cyclist, we then moved down Hunter St at about 8pm. When our vehicle turned left at Union St, we realised that this was not the road to Maitland. However, an hour and a half later we had loaded four tons of foodstuffs at the PDS depot by human chain consisting of a few police, army personnel and ourselves, in steady rain. By this time almost the whole of our cargo of yeast, flour, sugar, tea and tinned stuff was nice and wet, so with characteristic thoroughness, the army produced a large tarpaulin to cover everything and keep it that way.

At about 9.40pm our trek to Maitland really started. As by now the LVT was packed to capacity, we sat atop the tarpaulin exposed to the elements in all their wetness. With a clearance of only about 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 cms), we had to dodge under every overhanging street lamp, which kept us very much alert.

At about 11.30pm our vehicle pulled up in East Maitland, and we waited for further orders as to the destination of the food cargo, under which, by the way, was our equipment. After an hour’s delay we proceeded to East Maitland Police Station and unloaded the four tons of flour, sugar, tinned foods and yeast. The floor of the LVT was now awash with rainwater. Have you ever handled, stood in, rubbed against, slithered on, sat in, or even unloaded half a ton of wet yeast? Especially in steady rain on a steel floor, wearing rubber knee boots? And in the dark?

Sgt Boland, who was in charge at the police station, assured us that we could go to Maitland by army DUKW at first light – about 4.30am. As it was then 2am he suggested we go to the Boys High School where we could lie down for a couple of hours, and he even organised a car to take us there. Prior to leaving the Police Station I was fortunate in getting the use of the one available phone to ring 2KO so that they knew where we were.

At the school a cup of tea was available, after which we shed our wet clothes and stretched out on the floor of the assembly hall alongside a couple of hundred others, mostly evacuees from flooded homes. But at least we were out of the rain. Just as well the weather was warm.

Saturday, February 26, 1955

Dressed again at 4.15am, in rather damp and yeast-smelling clothes, we managed to get a lift on a lorry back to the police station by 4.30 am, just as dawn was breaking. No transport was going to Maitland so we decided to set up the VK 2AHA 80m transmitter on the spot for three reasons. In the first place, Sgt Boland was extremely anxious for another link with Newcastle, as only one telephone line was available to cope with exceptionally heavy official traffic. In the second place, much information about flood levels, etc, was to hand from Police Headquarters, which was what we wanted as broadcast material. And in the third place we had no means of transport to get away from there anyway.

In the half light of dawn I wandered down behind the police station towards a friendly looking tree from which to suspend one end of our aerial. On the way I almost ran into a huge RAAF truck complete with diesel engine and generator which housed its own 200-watt 80m transmitter. The RAAF operator told me they were working Williamtown constantly, and casually mentioned that we would have no chance of hearing any other signal while they were on the air on that band. Harold and I held a mass meeting and decided to try across the road at a private residence that had another friendly looking tree in the yard. Harold rang the doorbell at about 5am, and I fully expected someone to come out with a shot gun. But the occupants were most helpful and our thanks go to Mr and Mrs Frater of Lindsay St, East Maitland, who at that early hour moved their car out to give us full use of their garage. We moved our equipment in from the police station, and by now the rain had washed most of the yeast, etc, off our clothes and we were feeling fairly clean again, though rather damp. We rigged our aerial between the upper branches of the tree and the front fence, and after setting up the transmitter we sent out a call at about 6.30am.

At the second call we were answered by Jim Cowan who was operating his own portable ham station from the 2KO transmitter building at Sandgate. Several urgent police messages were sent on this link and as no land line was available to us, we passed our first flood bulletins by Ron Hurst in this manner to Sandgate from where they went by landline to the 2KO control room to be recorded ready for broadcast. A panicked messenger from the RAAF operator across the road complained that it was not possible for them to listen to other signals while we were on the air! This was a curious reversal of their earlier warning about their high power interference effect on our small transmitter!

Much urgent police and army traffic kept Harold and Jim very busy on their link. Meanwhile Ron Hurst collected flood information from Sgt Boland, and radioed short bulletins for broadcast when possible. By 9.30am Frank Hincks, the assistant to the Newcastle radio inspector (Mr Lobegiear),had his own ham station VK 2AA in operation and directed that all messages from VK 2AHA must go through his “official” setup. He also hinted that broadcast material must not clutter up that channel. In an attempt to overcome this difficulty Harold shifted frequency when doing Ron’s bulletins, but unfortunately the quality suffered due to extraneous noise at the receiving end.

Earlier, Merv Hardey of AWA had asked me if he could set up his FM unit in the garage with us, to which I readily agreed. He also installed a similar unit at the East Maitland telephone exchange. I knew we had a line from Maitland and I thought I might do some good in getting a line from East Maitland to that point, so I went off to the exchange leaving Ron and Harold to continue on from the garage in the meantime.

The East Maitland exchange was relatively new and wholly automatic, and therefore had no permanent technicians on duty. However, a number of linesmen operated from there, using the building as an office or centre, and they apparently kept an eye on the works each time they called in. Being lucky enough to meet up with three of them, I put my request for a line to Newcastle from anywhere they liked, but they assured me that this was impossible. Well then, I asked, how about a line to Maitland Exchange where it could be patched into our PL 1375 set? Yes, they thought this could be done, and in fact after very mature consideration they were sure it could be done, but not just yet. “Wait till the boss comes back.” After some time had crawled on the boss came in and had to put a few switches on and off to look really important before I could explain again what I wanted.

Yes, he could give me a line to Maitland by making an alteration on a pole down the street where there was a line not now in use, and I could have that. I hinted that time was rather precious, and at about 10.30am they assured me that about half an hour would have everything right. Seven men then loaded up a blitz wagon, hitched a trailer on the back and promised to pick me up at our garage as soon as the line was through. It must have been a terrific job or else they had no luck with the line, for I have not seen them since.

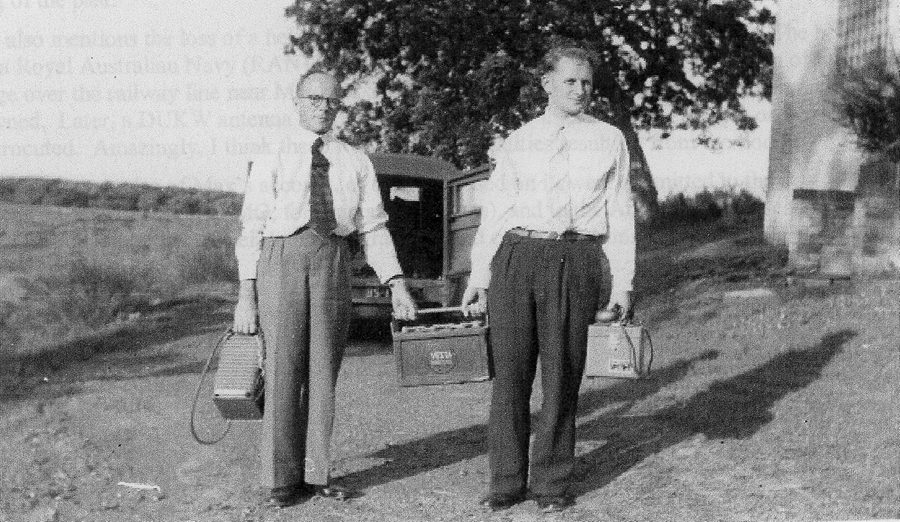

Lack of transport was handicapping us severely, cars were at a premium, and it was necessary for us to take a battery and an inverter with us when using the tape recorder as no power was available, even in East Maitland. However, after chasing a couple of false hopes, we approached Holme’s Radio Service and they granted us the use of their Holden car for the day.

With the recording equipment in the car we went to the water’s edge in East Maitland, through the RAAF road barrier – they were most helpful – and even past the “Harbour Master”. This was a unique personage, a civilian, apparently without any official authority but doing a good job in control of traffic on and off the floodwaters. Dubbed the “Harbour Master” by the surfboat crews, his instructions seemed to be obeyed by everyone, services people included. Ron Hurst made recordings at the water’s edge, which was as busy as Pitt St, and we returned in the Holden to pipe material to Newcastle via VK 2AHA and VK 2ZC, but again rather severe interference was noticeable at the receiving end. While sending this through to 2KO, Ron had collected more information from the police and we sent this along too. Towards lunch time on Saturday our position was bad, our radio link being troubled with interference, and we had no land-line available. Then an army DUKW pulled in at the police station and Ron immediately tackled the authorities who agreed to transport us to Maitland.

Harold was still very busy handling official police and army traffic with VK 2AA, so Ron and myself loaded up the tape recorder, battery and inverter onto the DUKW, and in no time we were off. On entering the flooded area we were met by another DUKW and informed of a fatality that had occurred a little earlier, when an aerial on a DUKW touched live wires and killed three people on board. The water was so high that in places we had to bob down going under power lines which could also have been lethal, and I know that all on board felt very relieved as each of these hazards was passed.

Our journey took us over South East Maitland flood waters to High Street Station where we crossed the railway, still waterborne, between the road traffic bridge and the Railway Station, there still being about 5 ft (1.5m) of water over the platform. We continued along High Street shopping centre, where it would have been possible in places to step out onto the shop awnings, then about 100 yards (100m) further up past the Post Office, and once again onto land that was free of water.

Further down Church St, where once again we became waterborne just short of the railway, we turned right into the very deep water below the Long Bridge. Here again, the hazards of what may have been live wires appeared, and we pulled down the DUKW’s aerial every time we approached what could have been a death trap. Up into Regent St and we cleared the water again just before reaching Campbells Hill, and then on to the hospital where we delivered stores and medical supplies. While travelling, Ron Hurst gave graphic descriptions of the terrible scenes we passed, all of which was recorded on tape.

On the return journey we received orders by radio to pick up three stretcher cases who urgently needed treatment at Maitland Hospital. One was taken aboard over a shop awning in High St, and two more from a temporary hospital that had been set up in the Maitland School in Church St, the same school housing about 1,500 other evacuees. To accommodate these casualties we built a platform of cases across the floor of the DUKW and a number of personnel were off-loaded by the police sergeant in charge. He was favourably disposed towards us and allowed us to remain on board. I had long talks with this officer while on our journeys on Saturday afternoon and found him to have a keen sense of the duty expected of him, and a quiet determination to do that duty. I later realised that I never learned his name, only that he was a Sergeant from Kogarah, Sydney. It was almost 7pm when we left the hospital at Campbells Hill, and the journey back over the water to Maitland in semi-darkness was uneventful but rather nerve-racking. It was then that we were ordered by radio not to attempt any more water crossings that night.

Leaving the battery and inverter on the DUKW, Ron and I took the tape recorder and held it high as we waded down to the Post Office through water and silt well up our thighs. I had an idea an FM outfit had been installed there by AWA and thought we would be able to get in touch with Harold Whyte at East Maitland to let him and 2KO know we were all right. We found, however, that the FM outfit was some distance down the street at the district engineer’s office surrounded by about eight or nine feet (about 3m) of water. Up till then, I had understood that the Maitland test room was operating from batteries, as of course no council power was available anywhere in that region.

However, I could hear the purr of a diesel engine and after some enquiries I found that the test room had its own AC supply from emergency plant. I approached the gentleman in charge of the telephone section, whose name I never learned, and asked was it possible and practicable for us to work directly into our PL 1375 from the test room itself? The request was granted and I was directed to the chief technician who was wholeheartedly behind the idea and immediately put a man on the job to set up our requirements. As the output of our tape machine was only a few ohms I asked if we could use one of their line amplifiers as well. The test room staff, although exceptionally busy, lost no time in fixing us up, even to terminating the line with a telephone type plug so that I could patch directly from the outlet jack of the tape machine.

We were also given a plate of stew made by some of the “Hello Girls” who were off duty but were unable to leave the building owing to the surrounding flood waters. Their cooking arrangement was rather interesting and novel. Their stew pans were held up over bunsen burners, but the result was very effective and even more acceptable.

I think it was about 8.30pm when we sent out the first bulletin over the line, and the test room boys were good enough to get an OK from Newcastle for us that the level and quality were in order. From then until Sunday night when Harold Whyte brought the receiver from East Maitland, we worked in the dark: we simply sent bulletins and information along the line and hoped for the best, as we had no means of checking that it was getting to Newcastle or if 2KO was using it. As the Police also had their headquarters in the post office building, Ron was able to get quite a deal of information of an official nature that we also sent down the line using the tape machine as a line or microphone amplifier. Not being able to get a check from Newcastle, I arranged that they should listen on each quarter hour and whatever information we could get we would put on the line at one of those intervals. We kept this up until the police officers decided to lie on the floor of their room for the rest of the night. As that closed our source of supply, we decided to do likewise, and lie on the floor alongside our gear in between the bays of the test room. That night we had a blanket each.

Sunday, February 27, 1955

Early Sunday morning Ron was still asleep and I was getting too sore to lie there any longer, so I went out and waded through the water and down to the Belmore Bridge to get the height of the river for an early morning news flash to the studio. When I returned I just got inside the door in time to hear the diesel which was driving the generator “conk out”. The exchange could carry on with batteries, but my batteries and inverter were on the DUKW, somewhere in Maitland. A word with the technician elicited the information that it was unknown how long the diesel would be out of action but the exchange could carry on from batteries for about 22 hours. So now we had a line but no power to make use of it.

I went back into High St at 5.45am looking for “our” DUKW to collect the battery and inverter. I found it in a side street being prepared for another day’s work and the radio operator using my 12 volt battery which he said was flat anyway. This completely robbed me of power so I decided to get back to East Maitland if possible and have the battery re-charged. I went back to the post office for Ron, and we then carried battery and inverter from the DUKW to a Newcastle Surf Club surfboat waiting about 300 yards (300m) away. The surf club boys rowed us over the two-mile (3km) course to East Maitland where the “Harbour Master” still appeared to rule the waves. As the boat grounded I strode up to him and told him I wanted the first available transport to control, which was the East Maitland Police Station. It worked, and in a few minutes he had us in a ute and on our way.

Back at the garage, Ron was able to give up-to-the-minute information not only on the position in Maitland City, but also about conditions that he had noted on our early morning trip back to East Maitland. These bulletins were all passed over the VK 2AHA to VK 2ZC link by radio, but unfortunately conditions at the receiving end were not ideal. While Harold and Ron were busy with this, I got our 12 volt battery down to Holmes’ Radio where they put it on a fairly fast charge and got back to the garage in time to join the boys at a plate of breakfast cereal organised by the Praters.

Later, I located a character with a 12 volt battery which he said we could have with pleasure, and I offered to go with him to collect it. However, he said it was no trouble for him and he would go down and bring it straight back as he knew we were very busy. I haven’t seen him since, and could not find out where he lived. Then by courtesy of AWA I spoke to one of the East Maitland PMG men by radiophone, only to find that no line could possibly be made available for broadcast use. Using Holmes’ Holden again we went out and made recorded interviews with surfboat crews, Salvation Army Canteen Officers and evacuees, but as our radio link with Newcastle was not all that could be desired, I decided to try to get back to Maitland exchange as soon as possible.

As I could not get hold of another battery I determined to take our own off the charger, where it had been for about three hours or perhaps a little more, and take the risk that it would see us out. Mr Holmes Jr collected Ron and me and the inverter from the garage, then picked up the battery from his charger, and drove us down to the water.

By this time I think the “Harbour Master” believed us to be like bad pennies or poor relations, especially when I asked for the first available boat to Maitland. He quickly had us on our way again by surfboat over the two miles (3km) of water, and by 2pm we were again on the end of our landline at the Maitland exchange from where I sent along the recordings we had made earlier in the day.

Meantime Ron Hurst went off to check conditions, river heights, etc, and as he had not returned by 3pm I passed on to Newcastle a few items of interest I had collected while he was away. This was done more to keep the continuity of reports than anything else, and before giving the information I mentioned that it could be knocked into shape by our news hounds and read by the announcer on duty. It was not until next day that I learned that my prestige had been lowered to that of announcer. The bulletin had been put straight on the air.

Ron Hurst came back with some apples, oranges, and a couple of bottles of Coke, so we had Sunday dinner. The rest of the afternoon kept us very busy going out, collecting information, then returning to pipe it down the line to Newcastle. About 6pm Harold Whyte arrived from East Maitland with the Ferris receiver and from then on we were able to get an OK over the air each time we sent material down the line. This seemed to bring Newcastle hundreds of miles closer to us as previously we had not been able to hear anything from 2KO while working from this point.

As we lay on the floor on Sunday night, Harold and I discussed the possibility of carrying the battery and inverter to selected spots next day to get “on the spot” recordings, and decided that we would give it a go. He would look after the battery, etc, while I brought the tape back and sent it down the line, then we would move on to the next location.

A point that had us all a little worried was the complete absence of fresh water. We were unable to wash ourselves or get water to drink, although a cup of tea was to be had occasionally from a large urn in the post office. It had become remarkably apparent to us that one uses water a surprising number of times each day, and as we had been without water for two days and we had three days’ growth of beard, were feeling pretty grubby.

Monday, February 28, 1955

Monday morning, up at daybreak to find the yard tap at the post office had running water. I know I practically had a bath in the yard and felt like a new man. Had a cup of tea in the post office for breakfast, then off to see what changes had taken place in the city overnight.

Down towards the Long Bridge the water was still very deep, but the beginning of Sempill St was clear of water although covered with 2 or 3 feet (35 to 60 cm) of silt. The river had dropped to about 32 feet (10m) and we went back and passed all this information down the line. Then down to Church St to the school from where evacuees were to be taken by DUKW across the water to Campbells Hill. Thence they were to be taken by bus to Greta Camp. Ron Hurst collected a great deal of official information there, which I took back and sent down the line. I later found that this also had been broadcast “as sent”. In fact one of our struggling publishing contemporaries next day found space to comment on some of my comments:

“Reporting happenings in Maitland yesterday a radio commentator said that even in such distressing circumstances there was still a spark of humour. It had been pointed out to him that the ‘Air Force is in charge of the roads, the Navy is in the air with its helicopters, and the Army is in the water with its DUKWs. That’s not where we expect to find any of these servicemen”.

Before returning to the school, I sought some means of transport for our recording equipment as a mile (1.5km) is a little far to carry a total of 128 pounds (58kg). Cars in Maitland City were very scarce as most had been removed to higher ground at Rutherford or East Maitland before the water got too high. Petrol was even scarcer, and although I had the use of a utility, I could not get any petrol for it. Some of the cars in town had been under water and the transport position was pretty grim. Four taxis were at the local taxi centre, but the drivers were all too busy at their homes, looking after their own interests, and the owner would not risk his “T Plates” by allowing anyone to drive them without a taxi licence. Finally he agreed to run the gear down to the school for me himself, and pick it up later in the day when he got the opportunity.

This was first-class and I quickly rejoined Ron and Harold, the former having teed up quite a deal more information of interest. We recorded from outside and inside the school, after which I carried the recorder back to the post office leaving Ron to chase up more material, and Harold to keep an eye on the battery and inverter. After putting the bulletin down the line I returned with the recorder, and from the school we carried the outfit down to the overbridge at Maitland Station.

At this point Ron interviewed Mr Fenwick who had been living on the bridge for four days, had witnessed the Navy helicopter tragedy the previous Friday, and who remembered the 1893 flood and was able to compare the water level then with what had been reached on this occasion. Alderman Kennedy of Maitland Council, who was also Chairman of the Northumberland County Council, was also interviewed. Leaving Harold to look after the battery and inverter, Ron and I set off back with the recorder. I left Ron at the taxi centre to await the return of the owner and then go back to pick up Harold and the heavy parts of our equipment. I went on with the recorder to send the material on it down the line to Newcastle.

While doing this I received a request from Merv Hardey by radio-phone from East Maitland, asking that Harold Whyte be made available to install one of the FM units at the Maitland hospital and get it into operation for an AWA Operator who would go along, too. When Harold and Ron came back with our gear, I told Harold of the request and pointed out that it was up to him, as Ron and I could carry on with our work. It was at about this time that we heard that we were to be relieved later in the day and taken out of Maitland. So Harold went to the hospital, installed the FM unit, then caught the first DUKW back to Maitland.

Ron and I, meantime, had collected the taxi again and taken the recording equipment as far as it was possible to go out through Lorn on the road to Bolwarra, where silt had been deposited up to five or six feet (about 2m) over the road. We also went to the point of first breakthrough of the water into Lorn, and recorded interviews at each place.

As the water receded on Monday afternoon, most of High St became “wadeable” and a constant procession of people tried their utmost to reach vacated premises as quickly as the falling water level would allow.

Our final bulletin was dispatched down the line at about 4.30pm. Shortly afterwards, Frank Cross and Ken Carroll arrived by DUKW to take over, for which we were extremely grateful.

The only means of transport was now by DUKW as the receding water made it impossible for the surfboats to operate. So off we set on our final trek through the streets of Maitland to the school, where we eventually clambered onto a DUKW at 6pm, and we were off on the first stage of our journey home. At East Maitland we almost fell into the 2KO Bedford, then up to the garage which had been our first base. We collected Harold’s transmitter and a few waterlogged clothes we had left there, and then headed for home via Buchanan and Bluegum, through West Wallsend and Cardiff, our journey ending about 9.30pm.

Thanks for hanging on to this material and (eventually) posting it here. It was fascinating.

Cheers Lachlan 🙂