My late friend and amateur historian Dulcie Hartley published several books during her lifetime, but one book she was very proud of never made it into print. This was her book about James Fletcher, Newcastle’s famous “miners’ advocate” – the only man in the city to be commemorated with a statue. Miner, politician and newspaper proprietor, Fletcher was immensely popular and influential, and Dulcie was fascinated by him. After Dulcie’s death, her daughter Venessa entrusted me with the manuscript, and I have slowly transcribed it.

Fletcher the employer and capitalist

During the early 1870s James Fletcher and the Birrell family became involved in land speculation, purchasing many allotments in the new suburb of Plattsburg. Birrell purchased Maryland Cottage and surrounding acreage. James Fletcher lived in this substantial home during his early years as manager of the Cooperative Colliery for William G. Laidley.

The Clarke family, later subdivided 50 acres – originally part of Dr Brooks Portion 24 – and in 1875 the Lemon Grove Estate was being sold by J.C. Bonarius from Harris’ Assembly Rooms at the Cooperative Inn on the corner of present-day Cowper and Murnin Streets. Fletcher and the Birrells made further speculative purchases in this estate.

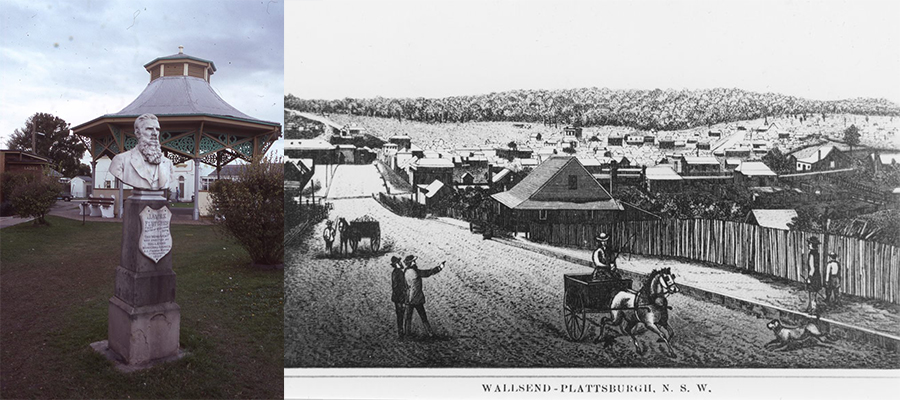

At the present time there stands in Rotunda Park on the corner of Nelson and Harris Streets, Wallsend, a bust of James Fletcher MLA. This land was originally Lots 5 and 6 in Section B of the Lemon Grove Estate, owned by Fletcher and sold to the Crown in 1881 for a handsome profit. Earlier known as the Plattsburg Reserve and later to become Rotunda Park, the land was often thought to have been donated by Fletcher to the citizens of Wallsend, but this was not the case.

During the 1870s James Fletcher’s energy and vitality were prodigious. As well as managing the Cooperative Colliery he became involved in local government. On April 22, 1874, the Wallsend Municipal Council was formed, with James Fletcher elected mayor at the first council meeting held in Harris’ Assembly Rooms on April 24.

Fletcher had also set himself up as a mining engineer and consultant and in the early years he operated as such from the Cooperative Colliery. In 1875, whilst employed as colliery viewer to the Greta Coal and Shale Company he gave a dinner at Gellatly’s Greta Inn for the workers who had successfully sunk a new shaft at Greta B Pit and struck coal. A regular feast graced the table, with turkeys, ducks, chickens, pork and ox tongue provided, as well as wine, ale, porter and cordials. The official party included Fletcher, Mr Vindin of the Greta Coal and Shale Co, Greta Colliery manager James Swinburn and W. Farthing, promoter and discoverer of the Anvil Creek Seam. The contractor, Henderson, was also in the party, as was Mr Harold from The Miners Advocate.

During this same year Fletcher was calling tenders for sinking on Messrs. Pope, Hardie & Co’s Catherine Hill Bay property. In 1879 Fletcher, together with his father-in-law, James Birrell, James Lindsay and others, successfully proved a third seam of coal on Kingscote’s Macquarie Coal Co’s Estate at Fassifern. In 1883 Fletcher supervised the diamond drill working at this mine, later to become known as the Northumberland Colliery.

In 1875 gold was discovered at Back Creek by sawmill proprietors Saxby and Bartlett. Soon known as the Barrington diggings, the name was changed in 1879 to Copeland in honour of the Minister for Mines, Henry Copeland. When news reached the mining communities in the Newcastle and Wallsend districts there was a general exodus to the diggings by coalminers, tradesmen and businessmen. Seamen in Newcastle Harbour deserted their ships to join the rush as rumours of rich finds were circulated. Some made their way by foot, and others travelled by coach through Raymond Terrace, Stroud and Gloucester, with a further very rough 10 miles to the diggings. Hundreds came by boat up the Williams River to Clarence Town where they disembarked to travel by coach to Dungog and then on to the diggings. Many of these travellers were from Sydney and storekeepers at Dungog were doing a roaring trade selling mining equipment. James Fletcher was involved in many of the mining syndicates formed, as was the Birrell family and well-known families from Minmi, Wallsend and Plattsburg. Alexander Johnson, late manager of J & A Browns’ Minmi pit had also joined the rush. He purchased the Prince Charlie Mine, a very good producer. Gold continued to be won for many years from this field with the Mountain Maid mine being the richest producer.

In 1876 Fletcher, with a journalist friend Mr Nelson, purchased the Galatea Hotel and the Newark Store in Lake Macquarie Road, (Darby Street) Newcastle. The Fletcher family later owned two hotels in Plattsburg: “The Jersey” in Nelson Street and “The Reserve” in Devon Street. Fortune favoured the Fletcher family during the latter 1870s.

Isabella’s old friends, Catherine and Henry Styles of “Styles Grove,” Minmi Road, were an aged, childless couple. Henry had migrated from Kent as a youngster in 1815 with his family, and in 1830 settled on 50 acres at the Big Swamps. Although he is credited with being the first to discover coal in the Minmi district, he pursued a successful farming career.[6] In 1876, after the death of the old couple, the farm, now only 25 acres, together with all buildings etc, was devised to Isabella Fletcher, “free from the debts of her husband”. Although there was a comfortable cottage on the property, generous William Laidley in 1878 transacted an agreement with Isabella and James in which it was mentioned that Laidley “is about to erect a building as a residence for the manager of a certain coal property of his, “on land belonging to Isabella, such residence to be leased by the Fletchers with an option to purchase for £1450. The Fletchers were empowered to hold the premises with Laidley or his executors at an annual rental of one peppercorn.

Known as “Styles Grove”, the home erected by Laidley, was an elegant two-storey brick building of fourteen rooms, built on stone foundations. Cedar was used extensively throughout the interior, and the drawing and dining rooms were divided by folding doors. Decorative cast iron surrounded the balconies and the roof was constructed of imported corrugated iron. An extensive underground cellar was provided. Servants quarters were included, as well as a commodious kitchen with the most modern appliances of the times. Outbuildings included a gardener’s cottage of four rooms with kitchen, as well as extensive stables. Within a short time Styles Grove was surrounded by beautifully landscaped grounds where peacocks paraded. The visitor approached the home by way of a decorative entrance bridge spanning a gully leading to a circular drive at the front door. The home became a showcase and a gracious lifestyle was enjoyed by the Fletcher family.

Soon after taking possession of the new home Fletcher leased adjoining lands from Fitzwilliam Wentworth, a descendant of William C. Wentworth. He was then able to run extensive herds of cattle and to offer land on agistment and for sub-leasing. In 1879 Fletcher was advertising “40 head of prime cattle” for sale.

James Fletcher was a devotee of horse racing, as well as the more lowly regarded dog coursing, and with the addition of the Wentworth Estate, he was able to indulge these interests. William Murray was overseer of the horse stud and in later years James Fletcher Jnr. managed the estate. In 1883 the Newcastle Herald reported that Fletcher’s champion greyhound Figaro had died suddenly. “Poisoning was suspected and the stomach contents were to be analysed in Sydney”.

Shortly afterwards Fletcher advertised his kennel of 21 valuable greyhounds for auction, perhaps to avoid further losses. During this same year the services of thoroughbred stallion Loup Garou, of 17 hands, standing at season at the Wentworth Swamps, was offered at £5. 5. 0 per mare. According to Sydney sporting writer, “Toet Cela”, this horse had won many V.R.C. and A.J.C. races and derbies, and was a favourite for the Randwick Ledger. “Toet Cela” even made a special trip to Styles Grove to inspect Loup Garou. The services of another prize horse, Sir Colin, a heavy draft horse of 17 hands, was also offered at £2.10.0 per mare.

Many servants were required at Styles Grove for the efficient operation of the property while the Fletcher family pursued a socially prominent role in the neighbourhood. Costs of maintaining the establishment were high, but income generated from the farm should have offset this outlay, together with that accruing from the Co-operative Colliery, the mining consultancy and the Herald.

It is interesting to speculate on the reaction of miners and workingmen in the Newcastle district to the elevation of their champion to the ranks of the landed gentry. Viewed in modern perspective, Fletcher’s upward social mobility and ostentatious trappings sat awkwardly on the shoulders of the “Miners’ Advocate”. As well, it must be remembered that in those days mine managers were regarded by the workers as being “next to God,” such was the power they wielded. Despite this, Fletcher retained his popularity during these years.

During 1880 James Fletcher was under pressure to stand as a candidate for the forthcoming election but he declined. However, towards the end of the year he reconsidered his position, accepted nomination and was duly elected. Fletcher was an active and effective member of Parliament, as revealed by the quantity of correspondence published in the Herald relating to local issues.

After Fletcher entered parliament the Cooperative Colliery was managed by James Fletcher Junior, although an arrangement was entered into with Laidley whereby the mine was worked on tribute. Fletcher continued his journalistic input to the Herald, and commuted to Sydney by overnight boat from Newcastle Harbour.

Mining matters continued to demand his attention and in 1882 he and James Jnr joined C. Sweetland, Manager of the Commercial Bank of Newcastle, with others in the Copper Mining Company at Captains Flat, on the Molonglo River. However, this was an unsuccessful venture and their mineral conditional purchase was later cancelled. The same year Fletcher, as Colliery Viewer, forwarded a report to the Department of Mines regarding a new coal mine being opened up for T. Garrett M.L.A. and his partner, Dr. W.F. Mackenzie at Mount Victoria.

In 1882 James Fletcher entered into partnership with Angus Cameron MLA as land, mining and property agents, operating from 97 Stephen Court, Elizabeth Street, Sydney. During this year Fletcher purchased property in Elizabeth Street for £1175, to be held in trust for Isabella, “free from the debts of her husband”. This phrase, so often appearing on conveyances when James Fletcher bought real estate, seemed to indicate that he had a premonition of his looming financial problems. After Fletcher entered parliament the decision was made to sell Styles Grove so the family could reside in Sydney. In 1881 the property was advertised for auction, but it did not sell so the family continued in residence.

Fletcher became involved with coal barons James and Alexander Brown when the ownership of Ferndale Colliery at Tighes Hill became the subject of litigation. The former owners, Messrs. Bingle and White, had mortgaged the colliery to Alexander Brown Jnr., of the firm J & A Brown, with power of sale, and on October 19, 1880 the colliery was sold for £20,000 to Messrs J. Fletcher Snr., Henry Law, Bank Manager, Charles F. Stokes, Manager of the Bank of New Zealand, and Charles Sweetland, Manager of the Commercial Bank of Newcastle.

This colliery was held in three shares, one each to Fletcher and Law, and one shared between Sweetland and Stokes. James Brown, senior partner of the firm J & A Brown, disassociated himself from the Ferndale dispute, stating that Alexander Brown Jnr., while manager of the firm, had signed the document behind his back.

On October 20, 1880, possession of the colliery was taken by force. One of the new part-owners of Ferndale, Henry Law, was a brother-in-law of Alexander Brown Jnr., and was at one time manager of the firm J & A Brown.

Fletcher became involved in the development of another mine when, in partnership with William Laidley, C. Dibbs, Charles F. Stokes and Thomas Brooks, they applied for permission to mine on 2848 acres at West Wallsend. In 1885 Fletcher became a provisional director of the West Wallsend Coal Co. Ltd. which, with capital of £90,000 in £1 shares, had every chance of success, especially in view of its influential board of provisional directors which included Colonial Treasurer George Dibbs and Alexander Brown.

In August 1885 Fletcher and other notables rode from Wallsend to inspect the site of the proposed West Wallsend Colliery and new township to house the colliery workers. A branch railway was , planned to connect with the Waratah-Homebush line so coals could be shipped from Newcastle harbour. By the time the colliery opened in 1888 the nucleus of West Wallsend township existed.

Coal mining was experiencing a boom and in 1885 James Fletcher was calling tenders for the sinking of a shaft at Bullock Island (Carrington), for the Hetton Coal Company. Fletcher once again entered into partnership with Henry Law, Charles F. Stokes and Charles Sweetland when, in 1886 they all owned quarter shares in Wickham & Bullock Island Coal Company, Maryville Coal Co., Tighes Hill Colliery and Ferndale Colliery.

Fletcher’s name now graced many boards of directors, especially after he entered Parliament. In 1885 he and fellow parliamentarian, Angus Cameron, were directors of the Mercantile Building, Land & Investment Co., of Pitt St, Sydney. Also at this time Fletcher was chairman of the board of South Cumberland Coal Mining Co, as well as the NSW Provident & Medical Association Ltd. Fletcher and Cameron were also provisional directors, in 1886, of the Sanitary, Ammonia and Patent Manure Manufacturing Co. of NSW Ltd., a firm intending to manufacture ammonia and guano from nightsoil and abattoir wastes. The disposal of night soil had always created great problems for local councils, and Fletcher was quite interested in this scheme which had been profitably implemented in New Zealand using Burt’s patent.

The year 1886 was most eventful for James Fletcher. In January he became a director of the Reef Gold Mining Company Ltd, formed to buy and work “a valuable gold mine” at Tia Reef on the Tia River, 23 miles from Walcha, with a modest capital of £5,000, in 20,000 five shilling shares. A shaft had been sunk to a depth of 100 ft. and it was reported that already gold to the value of £3,000 had been won. James Fletcher’s fellow directors in this venture were: Alexander Brown, merchant and coal proprietor of Newcastle, Samuel Clift, station owner of Maitland, Henry E. Stokes, merchant of Newcastle, and Thomas Bibby, coal mine manager. The success of this venture in unknown, although for a time gold was won from the Tia River district.

After Fletcher became Minister for Mines in the Jennings Ministry the family decided to move to Sydney. In March of 1886 their furniture and effects were taken from Styles Grove to a new residence, “Icasia”, on Old South Head Road, Woolarah. This was a large new home built by contractor George W. Kilminster, situated on Lots 2, 3 and 4 of Section E of Daniel Cooper’s Grafton Estate. The purchase price was £4,500, and the property was in Isabella Fletcher’s name, with Angus Cameron MLA as trustee.

Also during March James Fletcher, his father-in-law James Birrell, and young William B. Fletcher attended the opening of Camp Creek Shaft A of the South Cumberland Coal Mining Company on the Illawarra coalfields, a mine in which Fletcher had financial interests.

A major disaster occurred on March 18 when the Ferndale Colliery at Tighes Hill flooded and a miner, James Jenkins, lost his life. The flooding was caused by the waters of Throsby Creek filtering through the soil. “The ground was a mass of interstices, and due to a very high tide, the water advanced beyond its usual boundary and rushed into the mine. As it gained power and volume, it poured through crevices, dispersing all obstacles, cutting a channel until at last trees and hillocks fell into the torrent, and with a mighty roar, earth, timber and water poured into the opening of the mine, creating a gap eight feet wide. Then it was every man for himself rushing to a protected position, only to be forced from it as the waters rose. The men reached safety, with the exception of Jenkins and Hargreaves”.

The latter man was rescued, but Jenkins, a single man from the Wallsend district, was drowned. More than 100 men were thrown out of work. It was later decided to abandon the idea of pumping out the mine, so Jenkins’ body was never recovered.

Although Ferndale Pit was abandoned, some months later the manager, John Powell, was calling tenders for sinking a new shaft at Wickham for Ferndale Colliery, Fletcher and his associates having obtained a new lease. The poppet heads and outbuildings were removed from the old Ferndale site to the new shaft at Wickham.

The Ferndale Colliery disaster resulted in a Royal Commission and the official report was tabled by the Minister for Mines, James Fletcher M.L.A. Fletcher – who had sat on the Royal Commission and was co-owner of the Colliery the subject of the investigation – was accused by some members of the community of having a vested interest in the outcome of the enquiry. The Commission found that no blame was attached to the owners, officers or manager, although a recommendation was made for pillars to be increased in size beyond that which had previously been considered adequate in the Newcastle district. The Ferndale Colliery disaster and the resultant Royal Commission probably provided an impetus for Fletcher’s resignation in December 1886 as Minister for Mines. Although his official resignation gives other reasons, he did encounter a great deal of local criticism.

November of 1886 saw Fletcher once again embroiled in litigation at the Supreme Court in Equity. The plaintiff, Stockton Coal Co, had instigated proceedings against James Fletcher, W.A. Hutchinson, A.A.P. Tighe, W.A. Steel and Thomas Gunderson regarding ownership of Stockton lands. Fletcher, who had supervised the boring and sinking of shafts for the new Stockton Colliery, and his assistant, Mr Gunderson, were both accused of trespassing on Stockton lands owned by the Quigley Estate. After a lengthy hearing during which the ownership of the land was disputed, the verdict was given in favour of the Stockton Coal Co. However, the opening up of the Stockton Colliery proceeded under the ownership of James Fletcher M.L.A., Timothy O’Sullivan, a Newcastle Shipbuilder, and George Dibbs M.L.A (later Sir G.R. Dibbs, Premier of NSW.)

The mining industry was experiencing a downturn during 1886 and whilst the abovementioned case was in progress, other mining matters were claiming Fletcher’s attention. Shareholders and directors were concerned with the falling market and he presided at a meeting of the Wickham & Bullock Island Coal Co. Ltd. in the Sydney Chamber of Commerce. The Cumberland Coal & Iron Mining Co. Ltd. was also in financial difficulties and Fletcher presided at an extraordinary Meeting of Shareholders at the Sydney Hall of Commerce when it was decided to sell the property of the Company, together with South Cumberland Mining Co., to the Metropolitan Coal Company of Sydney. Fletcher was one of the largest shareholders in the Cumberland Company.

During 1886 James Fletcher, his son William and old friend Angus Cameron, together with several Sydney businessmen, encountered financial difficulties in regard to their purchase of land known as the Dover Heights Estate Subdivision. This created grave financial problems for James Fletcher, and later resulted in the bankruptcy of William Fletcher and Angus Cameron. The adversities of the year no doubt motivated Fletcher in December to again place Styles Grove on the market for Auction on 4 April, 1887, but once again the property was passed in.

Mr and Mrs. Anthony Ingram were then employed by Fletcher as live- in caretakers at Styles Grove and Ingram managed the property for some years.

Despite the adversities encountered during the year, the Hon. James Fletcher, now in dire financial straits, donated a Silver Cup valued at £5.5.0 to be competed for by the Wallsend Rifle Club. The Cup was a fashionable piece of Australiana in the shape of an emu egg and richly engraved. However, in view of the eventful year it was not surprising to learn in January 1887 that James Fletcher was very ill. Unfortunately there was an election pending, but he was so concerned about his health that he was considering retiring from politics due to the rigors of electioneering. However, his friends and supporters were anxious for him to continue in the seat of Newcastle so they decided to campaign on his behalf and he was successfully returned to parliament.

Due to his poor financial situation, James Fletcher applied himself tenaciously to his mining consultancy, now known as James Fletcher & Co. of 46 Castlereagh St. , Sydney. He advertised that “Reports on all description of mining property will be furnished by Mr Fletcher personally, and he is prepared to examine properties, provide plans and give detailed estimates of costs of sinking and machinery and advise upon all matters connected with mining generally.

Work certainly came his way and in March of 1887 tenders were called by the South Cumberland Coal Mining Co. Ltd. for construction of a railway line from the pit mouth to the Illawarra railway. Tenders were to be forwarded to the chairman, James Fletcher, at his business premises. His experiences as a consultant prompted him to confide to his old friend Thomas Abel, the Plattsburg Council Clerk: “If I give a gratuitous (mining) report it is considered valueless; but if I charge fifty guineas it is at once considered valuable”. In his professional capacity he prophesied that coal mine proprietors in another ten years would be glad to work the smaller seams which were then being ignored. At this time (1887) seams of less than six or seven feet were considered unprofitable.

With health somewhat improved Fletcher, accompanied by G.R. Dibbs, the former Colonial Treasurer, and a party of Newcastle and Sydney businessmen, travelled to Queensland to the Mount Morgan goldfields to inspect a goldmine that was on the market. Impressed by what they saw, the party purchased the mine – the Taranganba Proprietary Gold Company but it was later to prove a heavy financial burden for Fletcher when in 1889 an injunction was taken out against the company. The Directors were E. Vickery, G. R. Dibbs, J. Fletcher, W. Laidley, J. Keep and T.D. Merton.

Gold Fever

The Bonang Gold Mining Co. Ltd., formerly the New Rising Sun, was a similar project in the North Gippsland district of Victoria in which James Fletcher was involved, with 70,000 £1 shares having been sold to the public. The returns from this mine were advertised as varying between 1.5 and 11 oz. per ton. The provisional directors were well known parliamentarians W. Halliday, William Laidley, W.B. Walford, G.R. Dibbs, J. Fletcher, W.J. Lyne and J. Creer, as well as local businessmen D. Wilson, Alexander Brown, merchant and coal proprietor, Edmund Taylor from the Wallsend Coke Ovens, John Kidd, Henry Buchanan, Mayor of Newcastle, William Arnott, biscuit manufacturer and George Stenning. Fletcher was employed as manager of this mine. [29] During these years mining companies were floated with great regularity and James Fletcher, in his entrepreneurial role, must have pursued a highly mobile career. Fletcher and many of his contemporaries, infected with gold fever, were seeking their fortunes from this unreliable source. Certainly, if a bonanza was struck it could be worth a fortune, but Fletcher’s latter day gold mining ventures seemed destined to failure. There were rich quartz gold discoveries at Stewarts Brook in 1888, leading to the formation of the Northumberland Gold Mining Co., managed by G. W. Reay. Shareholders, mostly Wallsend and Plattsburg folk, were assured that the mine was yielding 20 oz. to the ton. Nevertheless, at the time of his death Reay had incurred heavy financial losses due to his gold mining interests, so it can be assumed that the Stewarts Brook mine was no Eldorado.

Another hopeful group of speculators formed the White Rock Central Silver Mining Co. with capital of £120,000 in £1 shares to purchase Watt’s mineral lease at Fairfield in NSW and James Fletcher was the prime mover in this venture.

At this time Fletcher had an impressive list of business responsibilities in the coal mining industry. He was managing director of Wickham & Bullock Island Colliery, managing director of Hetton Colliery, co-partner in Ferndale Colliery, manager of the Cooperative Colliery, together with the Metropolitan and South Cumberland Coal companies on the Illawarra fields. His financial situation was jeopardised in 1888 when 4000 miners were on strike for 11 weeks. Commenting on the strike, The Wallsend & Plattsburg Sun wrote: “The Hunter River miners had grievances which capital refused to redress and the solid phalanx of men declined to submit to them any longer and adopted the only course in their power”. James Curley, the Miners’ Secretary, was of the opinion that strikes were necessary as “proprietors will, at all times as well as work men, assume an exacting, imperious attitude, whether work men are prepared to accept such attitudes or not, and, were this to go unchecked, serfdom would be a condition of life. [32] It was due to the mediatory skills of James Fletcher. acting on behalf of the proprietors, and James Curley acting for the miners, that the 1888 strike was settled.

In 1889 James Fletcher received good news regarding the Bonang Gold Mine in Victoria. There had been an excellent sample crushing and the mine manager had wired him from Delegate of the results, advising that a crushing of 120 tons of stone had given a yield of over 150 ounces of retorted gold. [33] This report was indeed welcome as unfavourable news had emerged regarding the gold mine in Queensland. The Taranganba Proprietary Gold Co. had been formed with high hopes and a capital of £1,000,000. The original vendor, Robert Ross had reported returns of 82 oz. per ton and mining engineers McMilland & Munro had confirmed the mine’s viability. Fletcher’s company then employed their own mining engineer, Theodore Ranft, who confidentially reported 3 oz. to the ton at £4.2.0 per ounce. He opined that there were sufficient reserves for a life of 25 years and the field would be better than Mount Morgan. Unfortunately this was not the case and the mine was now worthless.

“Men of repute like those in the directorate have suffered heavily,” thundered the Sydney press, calling for exposure and punishment of persons who led the directors to believe they were purchasing another Mount Morgan, when instead they had purchased a stone quarry. James Fletcher suffered a severe financial loss with the failure of this mine. He held more than 57,000 shares, as well as having a one sixth share in a further 27,000, so his losses were enormous. He sadly prophesied that by his connection with this mine he had “hung a millstone around his neck” and it might take the remainder of his life to clear the debt.

Notwithstanding these debts, it was interesting to learn that Fletcher, together with his son James and many Wallsend and Teralba identities, became shareholders in the Woolshed Gold Mining Co., a company with a fully paid up capital of 30,000 10/- shares, in another attempt to win fortune from the elusive yellow mineral. Consequently, it was not surprising to find that in April of 1890 James Fletcher was stricken with a serious illness. A blood vessel in his nose ruptured and he haemorrhaged for several hours. Dr. Knaggs attended him and prescribed a lengthy period of rest. His staunch benefactor and family friend, William Laidley, perceiving the plight of the Fletcher family, waived the lease of 1 Styles Grove, and by deed of gift, conveyed the residence to Isabella with her father James Birrell nominated as Trustee.

District coal miners went out on strike in August of 1890 in support of the maritime strike which had erupted between ships’ officers and shipping owners over a salary dispute. As other unions followed suit an Australia-wide general strike ensued. There was international support for the strike and the Riverside Union of London forwarded £750 towards the Australian Strike Fund in September of 1890. Gold miners at Charters Towers decided to continue working but promised financial assistance. Union shearers decided to come out and those in the Bourke district were instructed by their union leaders to join the strike. The Trades and Labour Council discussed methods of preventing the supply of flour to any baker employing non-union labour. Great industrial unrest occurred throughout the country and it was reported that Bishop Stanton of Northern Queensland had admitted to labour leaders that he assisted in loading the steamer Palmer and would have done the same for unionists if they had been in a corner.

General strike

This paralysing strike created great community hardship and destitution, especially in view of the international economic crisis which eventually affected the Australian economy, leading to bank failures and depression.

Discussing the role of the trade union in parliament during the strike, James Fletcher spoke of the early days when he was regarded as a “stump orator” and a “breaker of the peace” because he was a union man. There was then a stigma attached to trade unionists and when he was appointed manager of the Minmi Colliery he discovered his name heading the list in the “black book” of miners who were not to be employed at any mine. Nevertheless, he was able to demonstrate that unionists were law abiding, capable workers and not lawless revolutionaries. Still speaking in defence of trade unionism, Fletcher mentioned his early days in mining when he worked 12 to 14 hours a day, with the result that often his wife had to massage his arms to restore the circulation so that he could sleep.

In those times the colliery owners rejected moves to shorten the working day, saying the coal trade and the country would be ruined. However, this forecast had proven incorrect and with the introduction of the eight hour day greater tonnages of coal were recovered, resulting in increased sales and higher profits.

Fletcher stressed the importance of a mediator to settle the current dispute, stating: “If there is only one condition (to ending the strike) and that is that trade unionism is to be stamped out, and that men are to be made subservient to the will of their masters . . . and brought back to a condition of beasts of burden, the strike will never end. This sympathetic statement from Fletcher, the mine proprietor, must have propelled the striking miners along the pathway towards negotiations for settlement of the strike.

During November of 1890 there was a conference of Northern Associated Colliery proprietors and representatives of the Hunter River Miners’ Association. The meeting was chaired by Jesse Gregson, president of the proprietors’ association and superintendent of the A.A. Co.

The miners wished to resume work under the conditions of the 1888 agreement but the proprietors, driving a hard bargain, wanted a guarantee from the men that they would not go out in support of other strikers again. They also wanted the union to rescind a resolution that members of the Coal Miners Union would not cut coal for vessels manned by free labour (scabs).

Chairman Gregson, together with some of the mine proprietors, attempted to humiliate the officers of the Hunter River Miners’ Association in their efforts to gain these concessions. Alexander Brown of the New Lambton Colliery, spoke in defence of the Union officers in an effort to allow them to retain some dignity. Fletcher played a valuable mediatory role with the result that the miners were allowed to resume work under the 1888 Agreement.

During the latter weeks of 1890 Fletcher’s health improved sufficiently to allow him to commence campaigning for the pending election at which he was duly returned.

James Fletcher during his public life had often referred to his many enemies, and that they existed was evident. There were also many who regarded his success with jealousy and envy, but his philosophy had changed little from the days of his involvement in the formation of the union and the Cooperative Colliery, when he considered it his duty to rise above the station of a collier. He had materially progressed from the calico tent of the goldfields to the miners’ hut, then to Maryland Cottage. There had been further elevation in his social standing with residence at Styles Grove, followed by the move to Sydney to live at Icasia, in the then fashionable suburb of Waverley. But the cost to his health and well-being had been tremendous. His prodigious energy and ambition, together with his political and business career should have resulted in comfort and financial security in old age, but unfortunately, this was not to be the case.