Like many Australians above a certain age, Jim Bradly was enchanted by the works of author Ion Idriess. In particular, Jim was captivated by the great storyteller’s depiction of the lost civilisation of the Torres Strait islands in his father’s copy of Idriess’s 1933 book, Drums of Mer.

I recently re-read that book as a precursor to writing this post, and I can readily understand Jim’s enthusiasm. Idriess was a master of “faction”, who built racy yarns on foundations of fact drawn from his extensive travels and his limitless curiosity. In Drums of Mer he imagines life as an Australian-born white man who has grown up as a captive of the people of Mer (mostly known these days as Murray Island). The premise is factual: there were such captives – notably from the 1834 wreck of the ship Charles Eaton – and Idriess explained something of the novel’s background in his last interview, granted to former ABC journalist Tim Bowden in 1975 and first published in 2020 as Ion Idriess, the Last Interview.

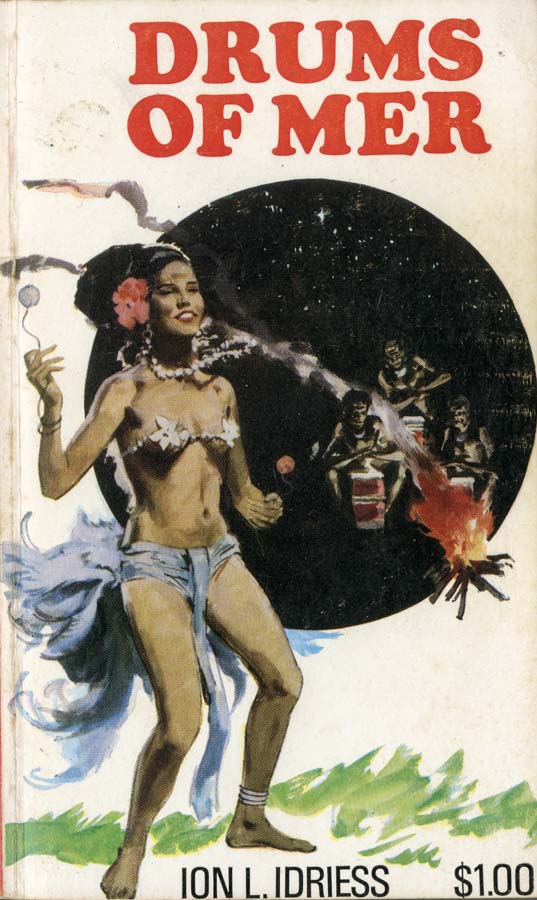

A cheap reprint of Drums of Mer

Unfortunately, Bowden’s book suffers a little from typos and mis-transcriptions, but it’s a good read all the same. On the topic of Drums of Mer, Idriess told Bowden that all the material came from interviews with old islander men to whom he was personally introduced by the missionary Rev. William McFarlane. “We used to sit down – McFarlane – and the old Zogo-le with the remnants around us in the Zogo house and I’d ask questions, and I’d write [down] the answers. McFarlane would ask of these old hands who’d been there all their lifetime and knew all the stories of their ancestors.” Idriess complained that his publisher, Angus and Robertson, prevailed on him to remove some of the more lurid accounts of island mysticism and magical practices, telling Bowden that “the most interesting chapters of the lot [were to be cut]. I took them back and I burnt them. I wish I never bloody well had.”

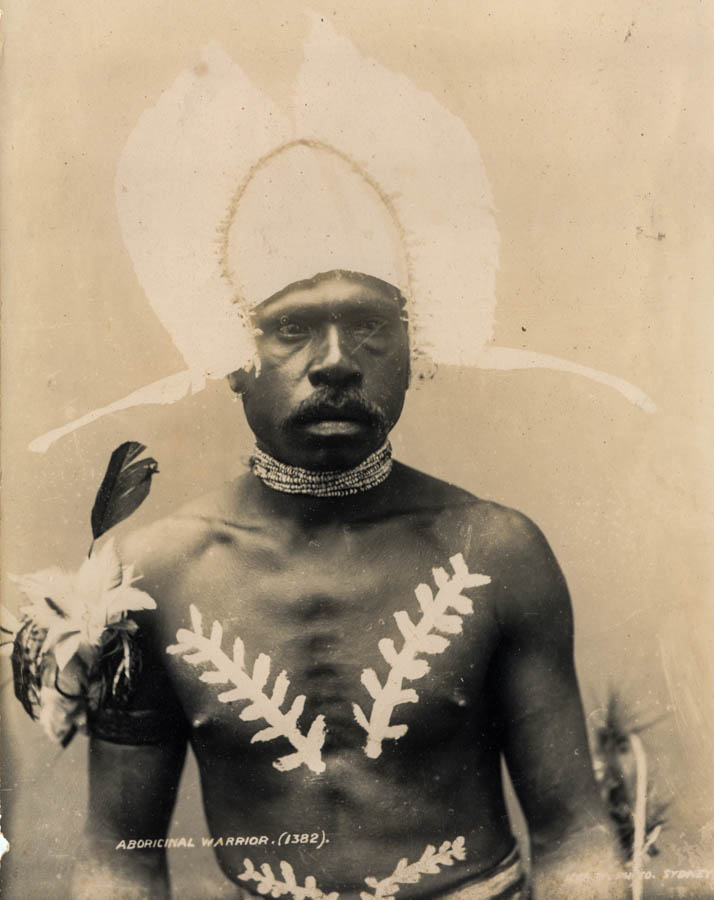

Not that the book is devoid of such content. It paints a very vivid picture of an advanced culture in which the mystical leaders played as big a role as the military ones. The islanders as depicted in the book were warlike, but also had quite sophisticated agricultural practices. They used fascinating technologies in weapons manufacture (the descriptions of some of the ingenious weapons are fairly horrific) and they were masters of navigation and seamanship who operated sophisticated trade networks that linked mainland Australia with New Guinea. Indeed, the description of this trading operation is one of the most interesting aspects of the book. Drums of Mer describes the island cultures towards the end of their traditional days, and depicts the pressures from European commercial exploitation (pearl shell, beche de mer etc) that hastened the cruel finale. The stories the old men told him were turned to good account as episodes in the book, and as reconstructions of important historical characters in island life. It must be said that the book is dated in a number of respects, and the casual racism doesn’t sit well to a modern reader. Actually, it seems almost as if Idriess includes these racist overtones as a sop to 1930s white readers, since his admiration for the islanders is vividly apparent, even though he certainly doesn’t try to glamourise every aspect of their way of life. Nor does Idriess write well about intimate relationships. A reading of Bowden’s book suggests this might be because the relationships in his own life were often perplexing to him as a man.

At any rate, putting these shortcomings aside, Drums of Mer is a typical Idriess yarn: exciting and informative. It can’t fail to leave a reader with any sort of imagination hungering to know more about these surprising island cultures and their deep histories. That was certainly how Jim Bradly was affected, to the extent that he resolved, some time in the early 1980s (he doesn’t actually recall the exact year) to go personally to Torres Strait and look for traces of the stories Idriess had told. It was a trip he had dreamed for years of making, and to his delight he found enough material to justify his hopes.

Before he left for the islands Jim visited Professor David Moore at the Australian Museum in Sydney who gave him a back-room tour of the museum’s Torres Strait islands collection before writing him a valuable letter of introduction to some key island leaders of the time, smoothing his way and opening doors that might otherwise have been closed. Jim read Moore’s book, Islanders and Aborigines at Cape York, based on journals from HMS Rattlesnake “containing, among other things, information about customs, lifestyle, language etc from Barbara Thompson who was held captive on Prince of Wales Island (Murralug) for nearly five years” [from 1844].

By phone, Jim arranged accommodation at Thursday Island, Murray Island (Mer), Yam Island (Iama) and Coconut Island (Poruma). On the ferry from Horn Island to Thursday Island the ferry operator realised that Jim was “that bloke from Newcastle who has been ringing me up all these years”. “I’ll be damned,” he exclaimed. From Thursday Island he flew to Iama where he met a direct descendant of the great warrior leader Kebisu (depicted in Idriess’s book) who kindly allowed Jim to hold and photograph the legendary ancestor’s great war club. Next he travelled to fabled Warrior Island (Tutu) where the most organised and notorious of the island cultures was based at the time of white contact. Here Jim saw the “place of shells” where the skulls of victims were once concealed from missionaries, and then managed to get lost for a time before finding his way back to the beach.

“From Yam Island you can see Two Brothers Island (Gebar),” wrote Jim. Gebar is said to be the site of a terrible tribal massacre – described in Drums of Mer – and there is a tradition that all visitors must leave a tribute gift of food or drink on the beach, with the strong local belief that failure to do so will result in misfortune.

Jim flew to Murray Island (Mer) via Darnley Island (Erub). On Mer, to his great pleasure, he met direct descendants of some of the people described in Idriess’s book and was greatly privileged to meet the custodian of one of the famous and legendary drums of the island’s ancient rituals. This custodian brought out two chairs and said: “Sit down and talk to me”. He spoke to Jim for a long time about the island’s history, culture and legends, then brought out the drum. He told Jim the drum’s name was Wasikor, and that a Japanese visitor had claimed to have seen its companion at Cambridge in England. Given that it was supposed to have been destroyed by missionaries, Jim regarded this lead as an important one to follow. Jim climbed Gelam, the extinct volcano on Mer and treasured the spectacular view across to the neighbour islands of Waeir and Douar, before almost passing out from heatstroke on his way up the slope.

He met a woman who told him of a childhood song about a girl with blue eyes, reminiscent of the castaway in Drums of Mer who went by the name of Eyes of the Sea. He met the last of the Malo men – adherents to Mer’s ancient indigenous religion, and another whose uncle was a policeman on the island when “a teacher took the Waiat effigy, now in the Queensland Museum”. He visited the ancient “sai” – stone fish traps – which legends state were built by the gods in the distant past.

Naturally Jim was interested to learn about the “treasure caves” which Idriess describes in his book. These are supposed to extend a long distance under the volcano, to connect with the sea, and to contain not only mummified ancestors but also relics of foreign ships wrecked long ago. Indeed, it is believed by some that survivors from a Spanish wreck centuries ago took over a village on Mer, and that their blood and names still survive in traces among the present-day inhabitants. Some islanders said they had seen the entrance to the cave, years ago, but none would give Jim any more specific information than that. His own searches were fruitless, of course.

Next Jim visited Waier, the headquarters in the distant past of the Waiat sex cult described by Idriess in Drums of Mer. It was a pretty island, Jim wrote, but eerie because of its strangely shaped volcanic rock formations.

Mer itself was captivating. Highly fertile, with a deep valley where the young men once underwent strict training for war, with banana gardens, secret quiet groves and tropical rainforest pockets. On the way back to the mainland he visited pretty Poruma, and then Warrior Island again, before rounding off the trip with a tour of Thursday Island.

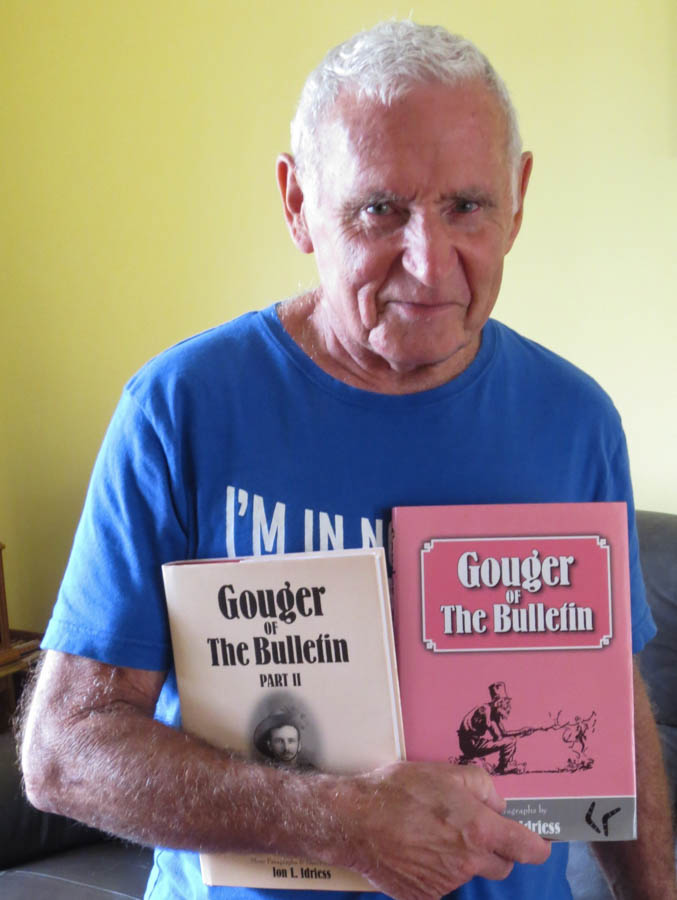

For a lover of the works of Ion Idriess, the tour was a wonderful treat. Perhaps the biggest pleasure was seeing that much of what the storyteller had described was borne out in reality. “That’s one of the things about Idriess,” Jim said. “He used to be frustrated that people assumed he was making everything up, but he really wasn’t. He was a great traveller, a great interviewer, a great listener, a great observer. So much of what you read in his books is founded on his real observations. He deserves to be rediscovered by new generations.”

Not surprisingly, Jim is an extremely enthusiastic collector of Idriess books and memorabilia, and he has published his own books of snippets of work that Idriess wrote under various pen-names in The Bulletin and other journals in the early part of his career.