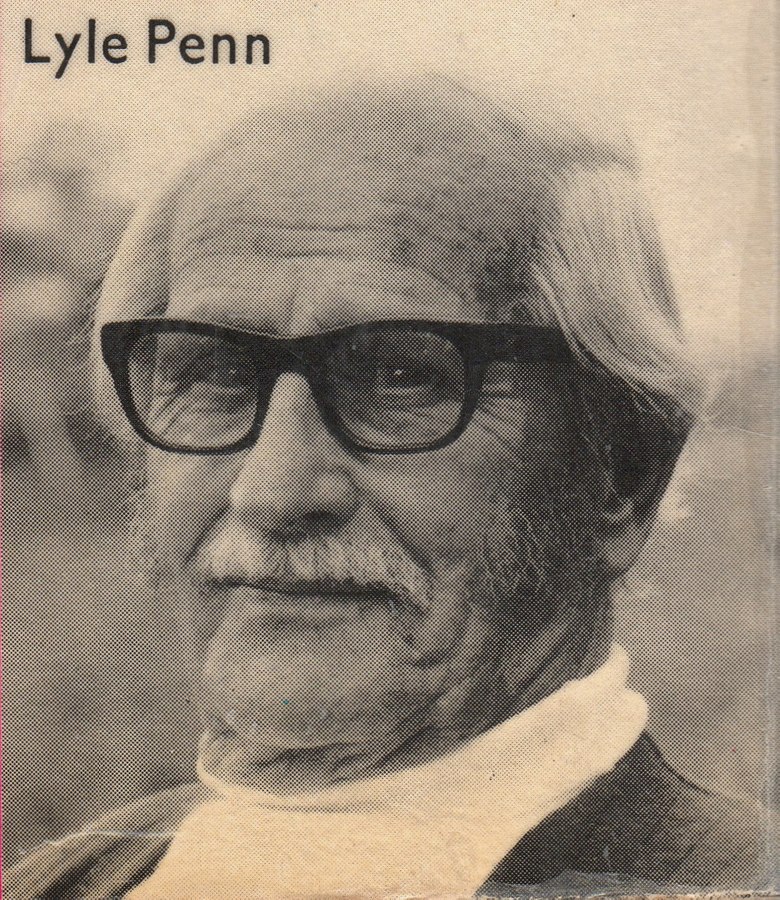

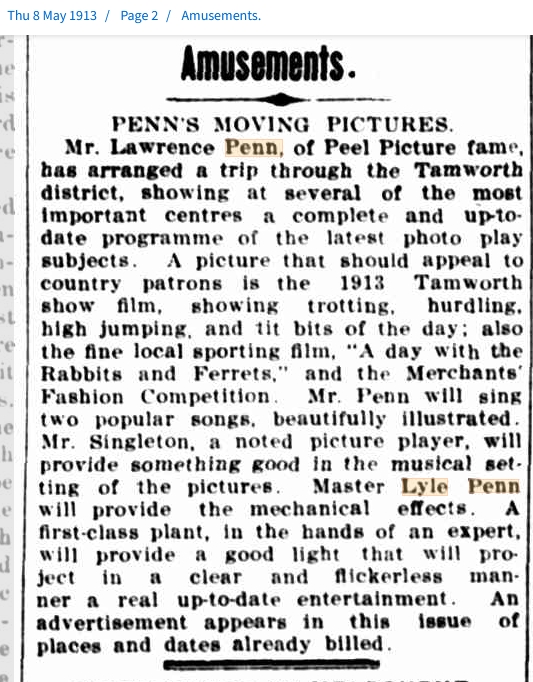

IN 1971 writerJoan Long was researching a documentary about Australian cinema in the 1920s. She wrote a letter to newspapers in a number of regional centres, trying to flush out stories and photos relevant to her work. The letter was picked up by NBN television in Newcastle which interviewed Long about her research. Among the people who watched the interview was a man named Lyle Penn, who had written a manuscript about his life as a travelling picture show man in the early years of the 20th century. Penn sent a copy of the manuscript to Long who loved the story and, after some years, used it as the basis for a feature film, The Picture Show Man, starring John Meillon and Rod Taylor.

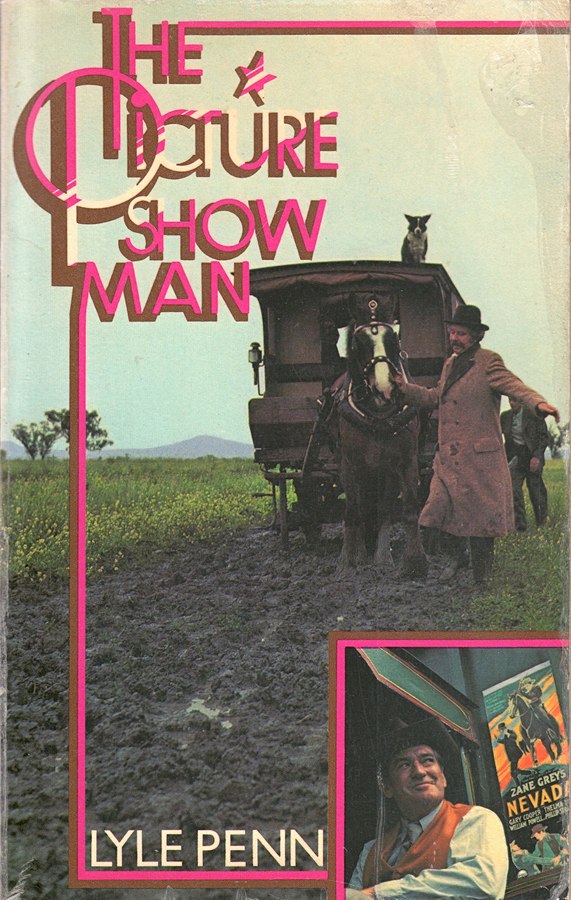

The 1977 film was based on Lyle Penn’s memoir, but the story – as is usual in such cases – differed considerably. It is pleasing to observe that the original memoir (edited by Martin Long) was also published in 1977. The book, a slim paperback also titled The Picture Show Man, caught my eye recently in a second-hand shop. It proved to be one of those books I couldn’t easily put down: a wonderful first-person tale of times and places long gone by, full of colour, humour and pathos.

The book tells the tale of young Lyle and his father, Pop Penn, who took their travelling picture show – an ancient limelight apparatus and some rented silent films – on the dusty and muddy roads from the Hunter Region to the Queensland border and beyond, accompanied by stoic horses and equally stoic pianists. As a Novocastrian I loved Penn’s description of Newcastle in 1909, when his father took up an offer from the firm Dix and Baker to run what might have been the first full-time picture show in the city.

In 1909 Newcastle was a city of steam trains, steam tram, steamships and more or less adjacent coalmines, all depositing their smoke, smell, soot and grit over everything you saw, smelled, breathed or touched. The long lines of wharves, which were in effect one side of the main street, were lined with ships (many in those days still under sail, with tall masts towering above the buildings), and they in turn added the odour of tar, rope and exotic cargo to the blended smell which was so typical of the city. The one main street was crowded with drays, carts, sulkies and drunken sailors – shanghai-ing sailors was still a major industry. But the place had a real personality, and at night, especially a wet night, with lights reflected on the wet streets and steam trams bustling around, it was lively and likeable.

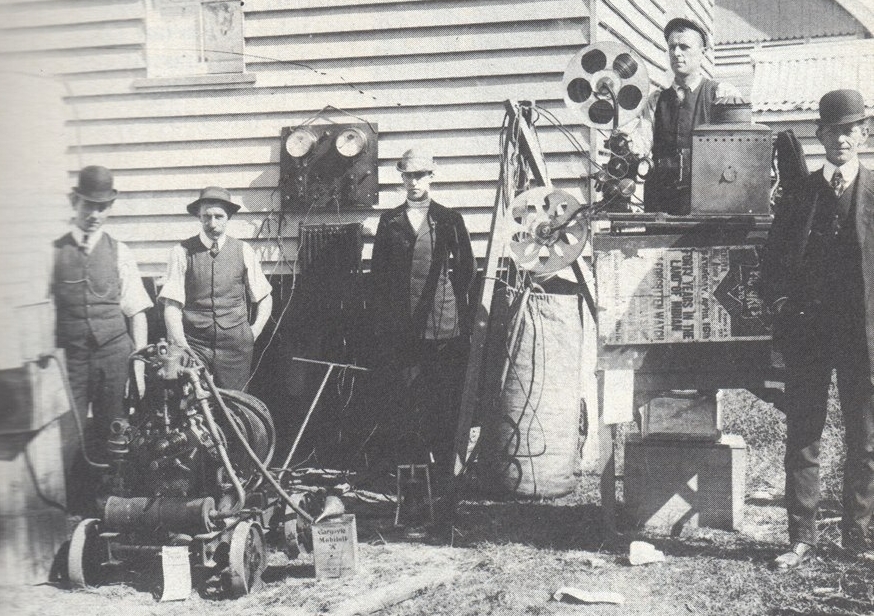

Before the widespread availability of electricity, limelight plants were common in a variety of applications including film shows. Lyle Penn’s description of the apparatus is priceless:

The lethal heart of the thing was a gadget called a separator, a group of four eighteen-inch long metal tubes with a two-and-a-half-inch bore, coupled together side by side and interconnected. These tubes were loosely packed with blanket material and sawdust and then filled with industrial ether, a fluid much more volatile than petrol. The surplus ether was drained off, thereby creating a cranky mixture of ether and air which was quite capable of blowing out the side of the hall.

The next component was an oxygen tank, consisting of two sections, the upper one fitting inside the lower, which contained water. As the oxygen was fed in, it displaced the water and forced the top section upwards, rather like a gasometer. The oxygen was made in the crudest manner possible: flat iron pots, about the size and shape of a meat pie, with a metal neck, were filled with a filthy black mixture and heated over enamel cups of methylated spirits. This produced oxygen, which was forced out of the neck of the pot through a rubber tube into the oxygen tank. The top of the tank was loaded down with house bricks to stop it going through the roof.

In front of all this the projector was set up and loaded with two thousand feet of highly flammable film on open spools, and the whole thing was placed right amongst the audience in a tinder-dry weatherboard hall. So here is what you had: a saturator filled with dangerously volatile spirit, a tank filled with oxygen, harmless in itself but dynamite if mixed with the ether, two thousand feet of inflammable nitrate film on open spools and an operator who smoked a pipe all the time he was running the projector. More than that: halfway through the show the oxygen tank would need replenishing and one of the oxygen retorts would be balanced on a homemade bracket over a half-full cup of methylated spirits.

From spool boy to mechanical effects

One of young Lyle’s jobs was “spool boy”:

My first job was to sit on a butter box in front of the projector and wind the used film on to a spool. It could be a very exciting and demanding job. If the picture proved too engrossing it was possible to find yourself waist-deep in a tangled mass of highly inflammable film which had to be untwisted and wound onto the spool before the top spool was emptied. If it wasn’t, the show was held up while the operator and the rewind boy sorted out the mess.

After being spool boy, he graduated to “mechanical effects”:

In an enclosure in front of, and to one side of, the screen was arranged an assortment of noisemakers that the effects man had to learn to use. There were three or four revolvers with a plentiful supply of blank cartridges, a sheet of galvanised iron for thunder, a coffin-sized box part-filled with marbles to simulate the sound of surf, a pair of coconut shells and a slab of marble for hoofbeats, along with doorbells, church bells and a dozen other things which now elude my memory but which a man (or boy) could have a very busy time with.

After a number of eventful years on and off the road with his father’s picture show ventures, Lyle parted ways from Penn’s Pictures in about 1920:

We had pulled up outside the hall in a little village called Booral, a little way north of Port Stephens. I was waiting in the car while Pop fetched the keys of the hall when across the paddock from a busy tennis court walked a tall dark girl with a nice figure and flashing dark eyes. The whole effect was very pleasing, and at that precise moment I decided that I would like to be married and settled down in my own house instead of lollygagging all around the countryside.

It’s funny how fate takes a hand in things. That very night, while the show was in progress, I collapsed the sudden onslaught of a sickness that had been creeping up on me for some time, the result of many years of living out of tins and sleeping out of doors. And lo and behold! The family that took me in and looked after me included the tall dark girl I had admired that very afternoon. I did not know it then, but my active association with Penn’s Pictures was over. I spent the next six months in hospital convalescing, and during that time my new-found girlfriend and I corresponded regularly. As soon as I was well enough I joined up with Hoyts Theatres in the city, married my Booral girlfriend, and Penn’s Pictures knew me no more.

Pop Penn died in 1952. An obituary can be seen here, on Trove.

I heartily recommend Lyle Penn’s wonderful little book. Second-hand copies are available. And if you would rather watch the movie, the trailer is on YouTube.

This article might be of interest in relation to your “Picture Show Man” story – my sister now owns the Herbert Family home

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/138154312?browse=ndp%3Abrowse%2Ftitle%2FN%2Ftitle%2F356%2F1918%2F04%2F05%2Fpage%2F15175465%2Farticle%2F138154312

Hi, when reading the book, The Picture Show Man, Lyle makes mention to shooting rabbits with a Winchester 32 rifle that is carried onboard their horse drawn waggon. I own that rifle. It was left to me by John Penn, Lyles great grandson after John was killed in a motor accident in 1975. It is a Winchester model 92.