Maitland is a city whose foundations were built on steam. And thanks to steam, the district was able to become one of the main drivers of economic growth in the young colony of New South Wales.

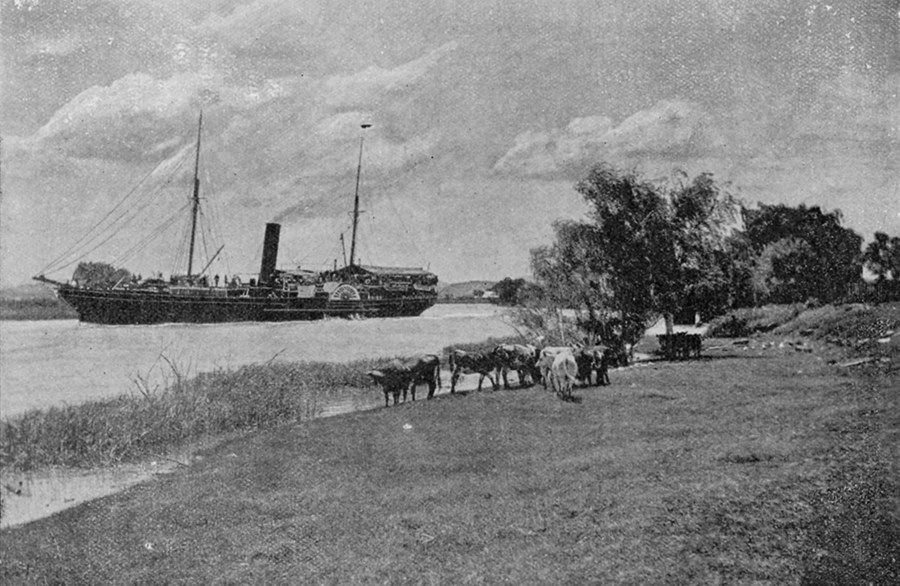

The Hunter River was always the key to Maitland’s future. Not only did the river produce the great wealth in the trees and soil of the floodplain, it also provided the highway to move produce from farm to market. Boats and canoes of various kinds regularly plied the river in the early days of European settlement and it is clear that the Indigenous people had been navigating the waterways for many centuries.

A regular boat service between Maitland and Newcastle was established in 1824 to service the settlers and farmers there and to bring their produce to the convict town where it was traded. To those using the river it was clear that Morpeth (then called the Green Hills) was the best place for a river port. The windings of the river and its relative shallowness between the Green Hills and the farms further west meant it made sense to carry goods overland to the practical head of navigation. By comparison to the easy river trip to the Green Hills, the overland journey from Newcastle to Wallis’ Plains (later Maitland) was a relatively arduous trek on a bridle track that wound through Hexham swamps. In winter the trip meant getting wet feet.

The rich farmlands of Wallis’ Plains grew in importance to the hungry colony. Newcastle became a free town after the convicts were moved to a new, more remote prison settlement at Port Macquarie, but struggled to find a post-convict identity and purpose. During the early phase of development in the Maitland district, Newcastle was no more than a decrepit staging post on the important trade route between the productive farmlands of Maitland and the Sydney marketplace.

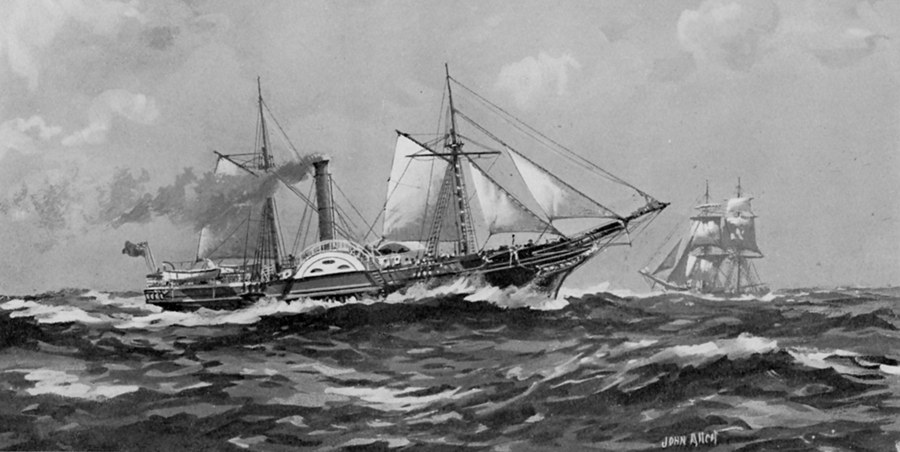

Sailing ships made regular trips between Hunter’s River and Sydney, (two early services were provided by the cutters Eclipse and Lord Liverpool) but sailing ships between the two centres were generally slow and uncomfortable. Rueful patrons nicknamed them “the stomach pumps”. The voyage from Hunter’s River to Sydney could take an unpredictable length of time and was hazardous, with an appreciable number of lives lost on the coast each year. The overland trip, on the other hand, involved a ride of at least three days over the mountains.

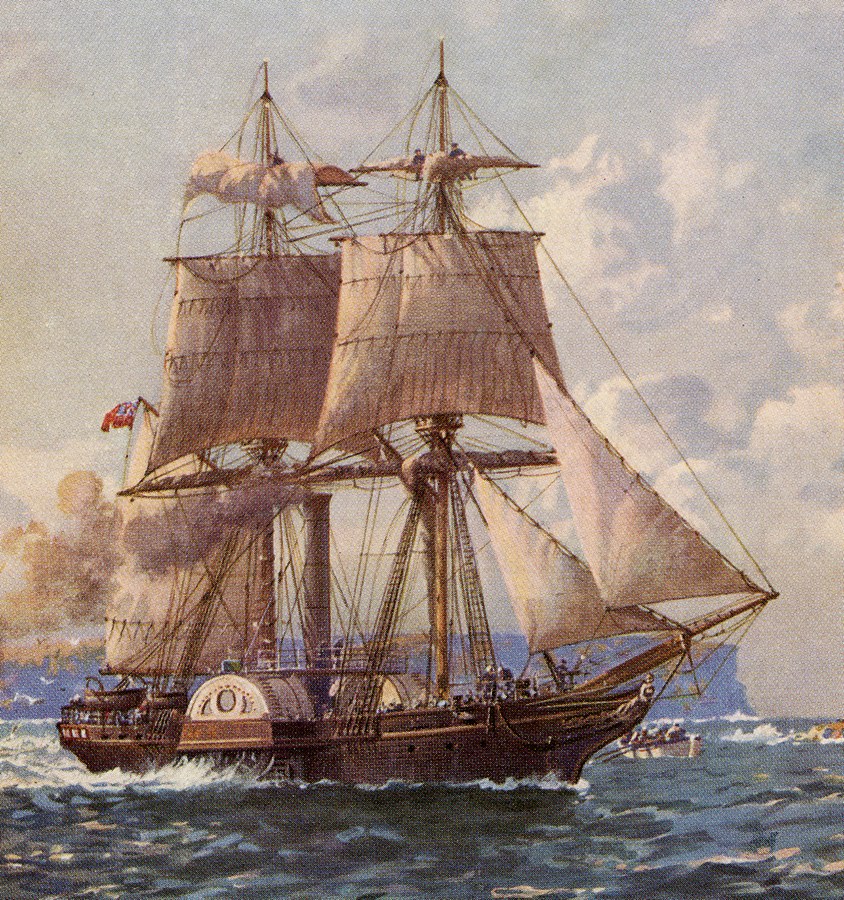

By 1829 it was plain to all that the colony of New South Wales could support a commercial steamboat service between Sydney and the Hunter River. Trouble is, such new-fangled vessels had not yet been seen in the southern oceans. There were some clever and well-trained Scottish shipwrights on the Williams River at Clarencetown though, and these men (James Marshall and William Lowe) were commissioned by Sydney merchant John Grose to build a steamer for the coastal trade. This was to be the famous William the Fourth.

But before the William the Fourth was finished, a strange steam-powered ship arrived unannounced in Sydney Harbour. This was the Sophia Jane, whose owner, a retired British naval officer named Edward Biddulph, had bought the ship as a speculative investment and sailed it to Australia. The Sophia Jane arrived at Sydney on May 14, 1831, beating the William the Fourth syndicate to the punch. It made its first voyage to the Hunter River on June 13, 1831, tying up at Newcastle overnight and making the three-and-a-half hour journey to the Green Hills next day. A correspondent described a trip on the Sophia Jane in the Sydney Gazette of October 1, 1831:

On landing at Newcastle some painful emotions are excited to find it in a ruinous and nearly deserted condition. It is now almost wholly possessed by the Australian Agricultural Co and may be estimated as their most valued possession, coals being now extensively consumed as fuel and rapidly increasing in demand. Departing from Newcastle, you glide rapidly into a spacious and beautiful bay, studded with numerous little islands thickly wooded to the water’s edge and abounding with pelicans, curlews, plovers, cormorants, ducks, teal, widgeons, sandlords and other birds . . . From hence you proceed swiftly and majestically along the verdant banks of Hunter’s River, adorned with the most luxuriant vegetation and studded occasionally with the primitive abodes of new settlers, and the temporary habitations of parties of the aborigines. You reach the Green Hills, where the steamer discharges her cargo into the store ship St Michael, which affords a most commodious warehouse, being roofed in and divided into compartments for the reception of goods for the steamer, to and from Sydney.

While the Sophia Jane was first to take advantage of the trade opportunity between Sydney and the Hunter River, the William the Fourth was not far behind. It was launched at Clarencetown on October 22, 1831 and sailed to Sydney where its engines were fitted. It made its first trip back to the Hunter River in February 1832, immediately becoming a great rival to the Sophia Jane.

James Tobias “Toby” Ryan briefly described a trip from Sydney to Newcastle in the William the Fourth in memoir, Reminiscences of Australia, noting that he and his companion paid “fifteen shillings each for our passage and miserable accommodation”.

The passage to Newcastle was very trying to us landsmen, sea-sickness being not the least of our troubles during the voyage of 14 hours. On arrival we pitched our tent on the side of a hill from which coal was being taken for the use of the prisoners and officers working at the breakwater at Nobby’s Island. We determined to stop a day there to recruit after our sea-sickness, the weather being in every way favourable. A great portion of the spot on which Newcastle now stands was then a bay or small arm of the sea, where the prisoners nearly out of their time and waiting their turn to get away were employed getting shells for lime-making for Sydney. The next day we proceeded on our journey to Maitland, and camped close to that pretty spot on the Hunter River where Morpeth now stands, about fifteen or eighteen miles from Newcastle. The Saint Michael, and old ship moored ready to receive goods for the country, proved an object of interest. We wended our way towards East Maitland along the Green Hills (so called then), the river in view all the time. On the western side , as we proceeded, a beautiful cedar bush came in view, covered with a flock of blue pigeons. We stayed four days in Maitland; two public houses and a couple of stores were all that could be seen in that locality. There was little to be seen about Maitland but what Nature had given, but, in this respect I must say she was bountifully supplied with a lovely stream running through a large area of some of the finest land under the sun; the river wending its way back to the sea at Newcastle. The wild duck could be seen in clouds flying about, and wild fowl of every kind were very numerous.

An immediate effect of the coming of steam to the coastal trade was a dramatic increase in the value of Hunter Valley property. The steamships gave the Hunter Valley a tremendous trade advantage over other farming areas of the colony, which had to rely on bullock teams for their heavy cartage, making freight much slower and much more expensive than that from the Green Hills.

More steamers followed: the Tamar, the Ceres, the Victoria, the Rose, the Shamrock and the Cornubia, to name a few. Companies and entrepreneurs rose and fell on the steam packet trade through the following decades.

The stunning river scenery was hit hard by European pioneers, many of whom left sensible farming practices at home, ring-barked the forests and mined the soil for all it was worth. In the 1850s the river trip was described in The Sydney Morning Herald by English writer Richard Rowe:

This then is the far-famed Hunter – muddy as the Thames, with banks as flat as Essex marshes! True, there are some pretty hills in the distance just before you come to Hexham, but, as a whole, the lower part of the Lower Hunter appears to be about as lovely as a plate of soup. I can find nothing to describe except the tall, white, leafless, barren trees, looking in the dim morning light like bands of spectres that ought to have been back in Hades a good hour ago.

For many years, Morpeth (as the Green Hills became) was a shipping port with an international reputation. Many settlers came to Australia through the port and when the Duke of Edinburgh visited Australia in 1868 he was carried to Morpeth aboard a steamer of the same name.

The first nail in the coffin of Morpeth’s prosperity came when Maitland and Newcastle were linked by railway in the 1850s. This meant that produce no longer had to come to Morpeth to be shipped, but could be sent by rail to Newcastle. Even the construction of a spur line to Morpeth did not stop the rot.

The heyday of the steamships ended in 1889 when the railway bridge over the Hawkesbury River was completed. Instantly the shipping traffic declined, and road and rail continued to make inroads into the Hunter River trade. It was a long decline, however and it was not until the 1950s when shipping services between the Hunter River and Sydney finally ceased.

Even before then the inexorable and lamentable processes of riverbank erosion and siltation had made their damaging marks. In his 1943 book The Newcastle Packets and the Hunter Valley, JHM Abbott wrote that the Archer and the Kindur were the last of the deep sea ships to come to Morpeth:

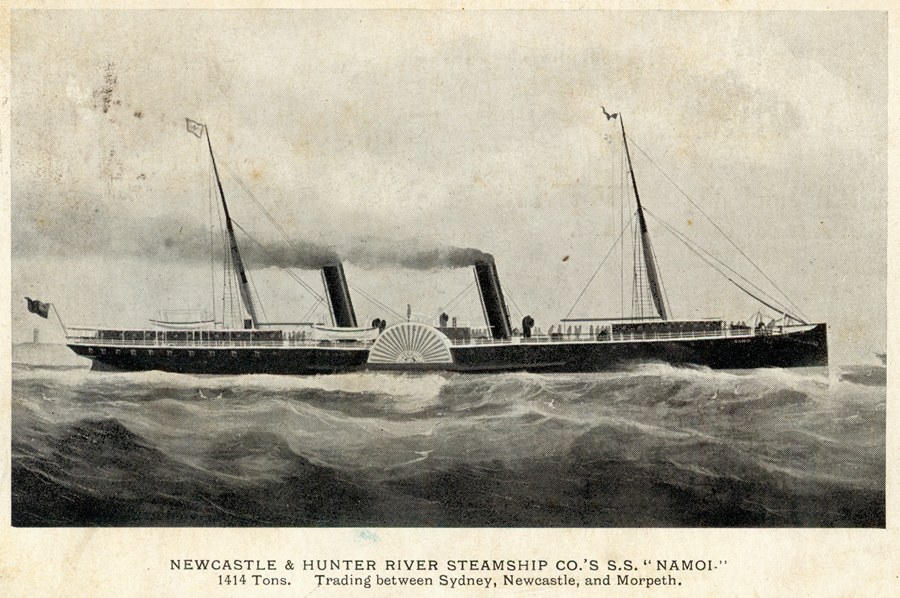

Formerly the passenger steamers plying between Sydney and the Hunter invariably continued their voyage on from Newcastle to Morpeth, but they never do so now. The gradual but inexorable shoaling of the river accounts for this. The last of the larger vessels of the Newcastle and Hunter River Company to make the complete voyage was the Namoi, but when the Archer and Kindur used to make it, say, a dozen years ago, it was only possible to get them up to the Morpeth wharf on the flood tide.

The last steamer to make the trip to Morpeth is said to have been the Doepel, in 1946.

The beautiful river had become unrecognisable. Writing in 1948 in his book, Red Cedar, P.J. Hurley deplored the damage. “The Hunter looks like a poor meandering old stream . . . so much of its water has gone underground, owing to siltation. There was tragedy, he wrote, in “stark staring hilltops, denuded of tree cover.” “Their sides are rowelled with runways. Gullies show where the precious soil crust has been gouged by stormwater. The silt in the river came from these hills.”

Steamers named Maitland

There were two steamers named Maitland.

The first was a little wooden paddle wheeler built at Pyrmont in 1838. This ship, 103 tons, ran between Sydney and Morpeth twice a week for a few years before being put on the Port Macquarie run. It came back to the Hunter in the 1840s before being sent to Melbourne as a tug. The ship sank, was refloated and renamed Samson, sent to New Zealand where it was finally wrecked in the late 1860s.

The second Maitland was a serious ship. At 880 tons, this iron paddle steamer was built at Glasgow in 1870, arriving in New South Wales a year later where it began operating on the Sydney to Hunter River Run. On May 6, 1898, it was wrecked at Cape Three Points, Broken Bay, in a gale that was later named the Maitland Gale at a place that is now called Maitland Bay.

The Maitland left Sydney with 63 passengers and crew in the face of the gale and mountainous seas. Waves smashed their way into the ship, eventually putting out the engine fires. The Maitland drifted helplessly onto rocks where it broke apart with the loss of 21 lives.

There was also a steamboat which was to be named the West Maitlander, but was actually launched as Huntress. This boat was was built in the late 1830s and launched in 1841 by a group of Maitland businesspeople who wanted to take freight straight from Maitland to Newcastle, without using the existing shipping facilities at Morpeth. The boat never got its engines, apparently, and was said to have been torn from its moorings in the 1847 flood and deposited, high and dry onshore, where it was left to fall apart.