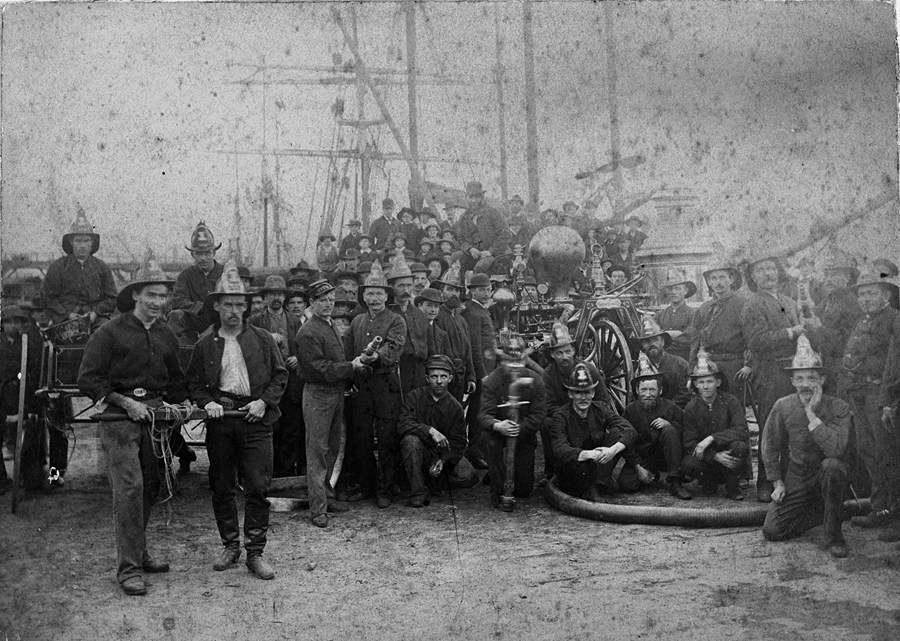

I once shared this photo on social media, along with the information supplied by its previous owner, former fireman and collector the late Ken Magor. That information said the photo depicted the christening of the first steam fire engine owned by Honeysuckle Volunteer Fire Brigade, in Newcastle, NSW.

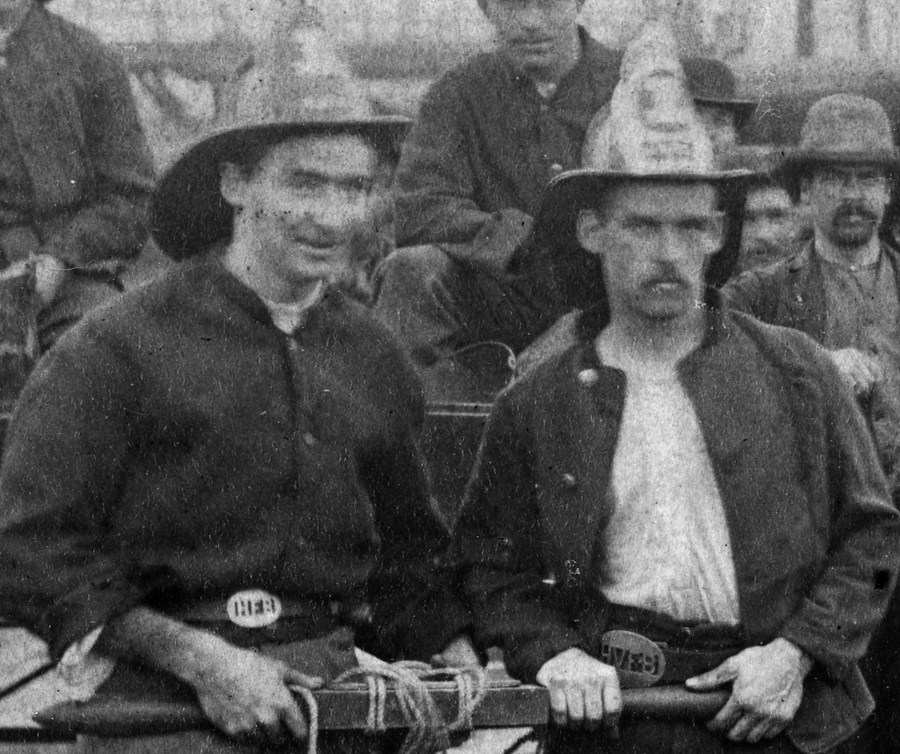

A good many people insisted that there was no way this photo could be in Newcastle because the helmets the men were wearing were American, of a type not used in Australia. Chastened, I retreated behind my usual lame excuse; that I was depending on information supplied. Mind you, I still thought it was a Newcastle photo, because I imagined I could read the word “Honeysuckle” in ornate script on the engine, and because the lettering on the various helmets and belt buckles worn as part of the mens’ mismatched uniforms seemed to bear initials that supported the case.

You might imagine, then, that I was pleased to discover – quite by chance – that Newcastle’s Honeysuckle Volunteer Fire Brigade did indeed wear American helmets. The information was in an article in The Newcastle Morning Herald of April 8, 1886, which described how the “christening and grand trial of the new steam engine” was to take place that day. The article gave a good description of the planned events, and then mentioned that the volunteers were “also going to wear the American helmets, a novelty in Australia”. The American helmets came, it appears, with the American-made steam fire engine.

A later article in the Herald March 19, 1891, gave a potted history of the Honeysuckle Volunteer Fire Brigade, mentioning how it had, in the 1880s, ordered “a full-sized steamer engine”. “This, with a thousand feet of the best American hose, an additional hose reel, 36 American fire hats, 600 feet of canvas hose, a hose cart, couplings, torches and tools, altogether amounting to over £1000, came to hand some twelve months later and the brigade was then placed on a footing equal to that of any similar institution outside the metropolis.”

So much for the objection to the American helmets! Now I feel safer to assume that Ken Magor’s information is correct and the photo was probably taken in April 1886 at the christening of the “new steam engine”. According to the Herald article from that date, the appliance was to leave Honeysuckle Fire Station at 2.15pm in a procession headed by the Newcastle City Band. Following the Honeysuckle volunteers would be those of the Lambton and City brigades with their appliances, en route to the grounds of the asylum. After some preliminaries, the trial would start, with the firemen demonstrating how quickly they could get their engines into action, and how far the machines could squirt their jets of water.

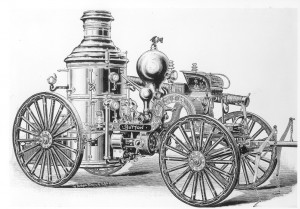

At the time the Honeysuckle Volunteer Fire Brigade was shopping for a steam fire engine, those made by the English firm Merryweather and Sons were state of the art.

(photo by H. Zell)

According to the 1891 article linked above, the Honeysuckle Volunteer Fire Brigade was formed in 1882 after a number of fires had broken out in that part of town, a little too far west for the volunteers of the City brigade to be able to reach in time. The new brigade started with 10 men and a small hand engine and was based near the Post Office Hotel. It was soon realised these arrangements were inadequate, so a manual engine and hose reel were acquired. I wonder if this manual engine is the one named “Little Wonder”, mentioned in this article about the machine’s restoration by the volunteers? Next, new premises – “on a piece of ground adjoining the mortuary” with a building funded by the municipal council. This new building was opened in March 1885. Next came the big new steam engine and accessories – with the American helmets, of course – and by 1891 it boasted 30 well-trained members. The fire station had a bedroom to accommodate four men on call.

Ken Magor collection.

“One of the great advantages of the site of the station is its close proximity to the Honeysuckle Point Railway Station which gives great facility in getting the members and their implements away by train with the utmost expedition should their services be required at any point along the the railway line,” the article noted, adding that: “Since 13th December last the Honeysuckle Brigade has turned out to sixteen fires, and since its inception the members have attended over 200 outbreaks”.

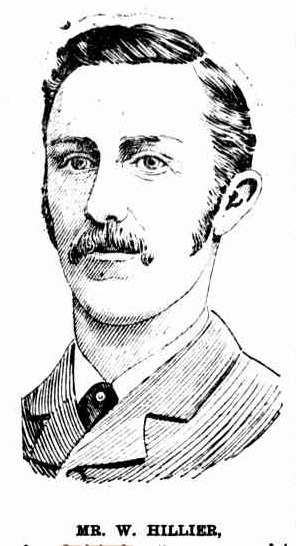

The purchase of the steam pumping engine followed an intense fund-raising effort, presided over by the brigade secretary W. Hillier, who received in thanks an inscribed gold cross at the brigade’s annual general meeting in March 1885. It seems the brigade members resolved to buy one of the famous British-built Merryweather and Sons machines, but ultimately opted for an American device, made by the Button Fire Engine Company of New York. The machine is described in this Herald article of April 1, 1886. The article stated that “the engine is guaranteed to throw water horizontally, when using 100 feet hose, above 230 feet”. “It will, if required, throw four good working streams over the highest buildings in town”. “The machine is a most beautiful one to the eye, and is the only one of the kind in Australia”. “The brigade have received a full complement of helmets, made on the most approved principles,” the article noted.

American-made Button steamer similar to the one bought by the Honeysuckle volunteers. (See photo above.)

These early brigades were promoted by local businesses and property owners who stood to lose fortunes through fires, especially since so many of Newcastle’s early buildings were built of pitch pine and similar flammable materials and since insurance covered relatively little of the damage in many cases. According to the Herald, the total value of property destroyed by fire in 1884 was £23,000, with only £9,302 of that covered by insurance. It was thought that the Newcastle brigades had saved businesses about £60,000 over that period.

The role of insurance companies at the time was often deplored. Until they were forced by legislation to provide some support to fire-fighters, they were mostly content to let the volunteer fire brigades pay for the privilege of saving the insurers huge sums.

W. Hillier, mentioned above as a prime-mover in the purchase of the engine, had come to Newcastle in 1880. Having previously been involved in fire brigades he set about having one established at Honeysuckle Point. He was appointed honorary secretary six months after the brigade was formed on August 6, 1882 and when an article about him was written in the Herald on June 28, 1897, he was still in the role.

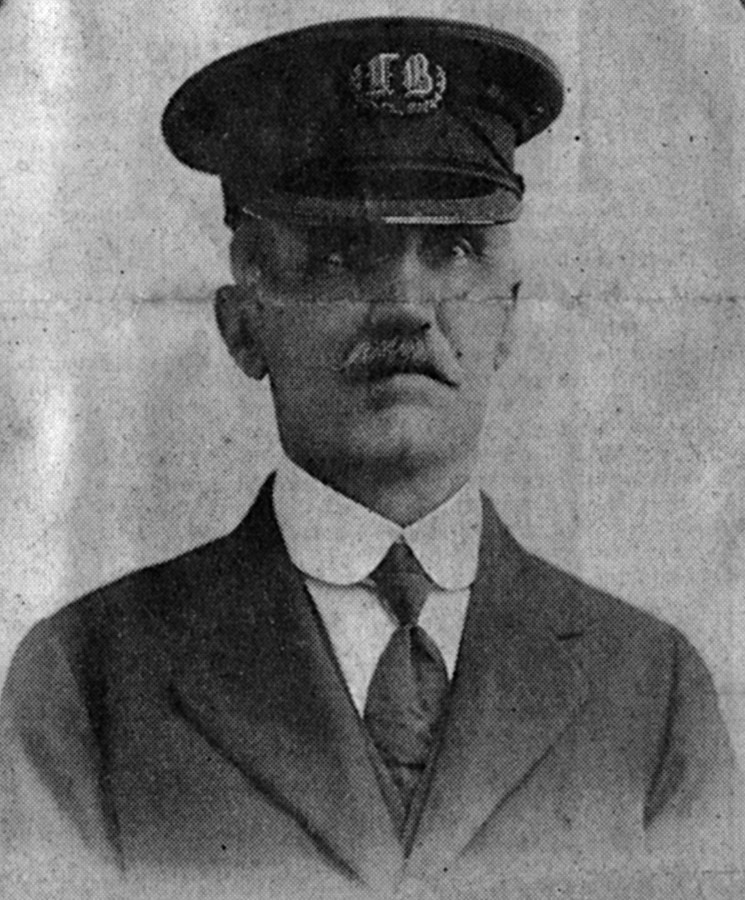

In an interesting article in the Herald on July 6, 1974, Mr Hillier’s grand-daughter, Yvonne Webb Jay, described staying with her grandparents when she was very young. Above the door in her grandfather’s bedroom was a very large bell that would ring if a fire was reported in the area. Mr Hillier was a district officer at that time, and Yvonne wrote that when the bell rang, he would hastily don “the trousers, boots and coat that were always carefully set on the chair beside his bed” and run to the nearby fire station in Union Street, Cooks Hill.

She noted that in earlier times her grandfather had been “among the band of gallant volunteers who ran to the scene of each fire, pulling a hose on a large reel. Ken Magor wrote a brief account of how fires were fought in the early days, giving Tighes Hill Fire Station as an example. This station, he wrote, was a three-roomed structure featuring a 30-foot bell tower and above that a lookout that provided a fairly good vantage point for the suburb.

“A fire starts in an old Tighes Hill home. A neighbour or some other person mounts a bicycle and pedals furiously to the fire station. The fire bell clangs and the volunteers – many of them at their trade in the area – drop their tools and run to the station. Smoke billows above the housetops and from the lookout the location of the fire is roughly established. The firemen change into their uniforms and when sufficient men are available the two fire hoses – each 1000 feet long – wound onto reels attached to the two-wheeled cart which has a shaft and crossbar and is operated by human horsepower. The firemen push the reel out onto Maitland Road. With the fire bell clanging they jog off at a steady pace in the direction of the fire. Whilst heading for the fire a steam tram comes along. The tram stops and the firemen carrying the standpipe and branch hop aboard. The reel is shifted to the rear of the tram and the rest of the men jump aboard. By holding the crossbar they get a lift. Half-a-mile further on they disembark and jog to the fire with a fair crowd following,” Ken wrote.

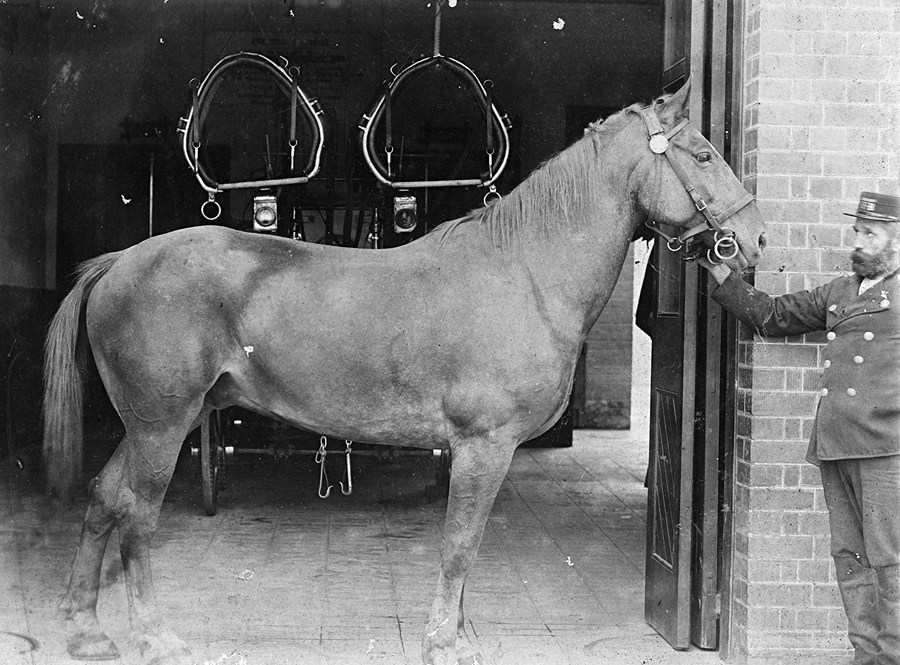

By the time she was staying with her grandparents, Yvonne Webb Jay wrote, “the manpower had been replaced by two horsepower. They were called Ranji and Derwent. When they heard the fire bell they would quiver with joyous excitement, paw the ground, impatiently waiting for the door of the stall to rise foward and allow them to enter the cement-floored station. Superbly drilled they would position themselves under the shining polished harness which was suspended from the ceiling. This was then dropped over them and men at either side swiftly fastened the buckles.”

“Fires were almost a social event and were well-patronised. Certainly the sight of the two horses drawing the fire cart, plunging along the street at a grand pace, provided a thrill no mechanised vehicle could ever equal,” she wrote. Those “who were able to drop what they were doing immediately did so and went to the fire; children flocked to the scene.”

Another description of the horse-drawn steam fire pumps in action appeared in an article by Leo Butler in the Herald of October 3, 1953: “With the boiler belching flame and smoke and the horses hooves thundering down the street, the Volunteers clattered to a standstill, the hoses were run out, the harness unhooked and the cool, courageous horses trotted to their station.”

Not all horses liked to attend fires, apparently. In another Herald article of March 3, 1960, Leo Butler quoted a Mr Walter Scott (apparently one of the last of Newcastle’s former hansom cab drivers) claiming that some cab drivers used to run the fire wagons. From their rank outside the post office, when they heard the fire bell – “anyone could ring it. It was just up a ladder and anyone who knew about the fire went up the ladder and set the bell going” – they would “race up to the old fire station at Pacific Park, . . . take the horse out of the cab and put him in the hose-reel waggon.” “Then we’d dart off to the fire,” Mr Scott reminisced.

One night he described how his brother had just gone through this exercise and was heading down Scott Street in a hurry with the cab horse pulling the hose-reel wagon. “But as soon as the old horse (who had been to a fire before and didn’t like them) got to the Great Northern corner, he propped and lay down on the road. He wouldn’t take any notice and they had to take him out of the shafts and push the reel waggon back to the fire station,” Mr Scott said.

He also recalled another fire at Mayfield. The bell rang about 10am and he put his cab horse – a beautiful trotter named Jack – into the hose-reel wagon and set off on the long drive to Mayfield. “Jack, like all the horses, detested fires. But out we went to Mayfield. I suppose it took us a fair while to get there with the hose, it being a fair way to Mayfield. When we got there, there was nothing to do for the house was completely burnt,” he said.