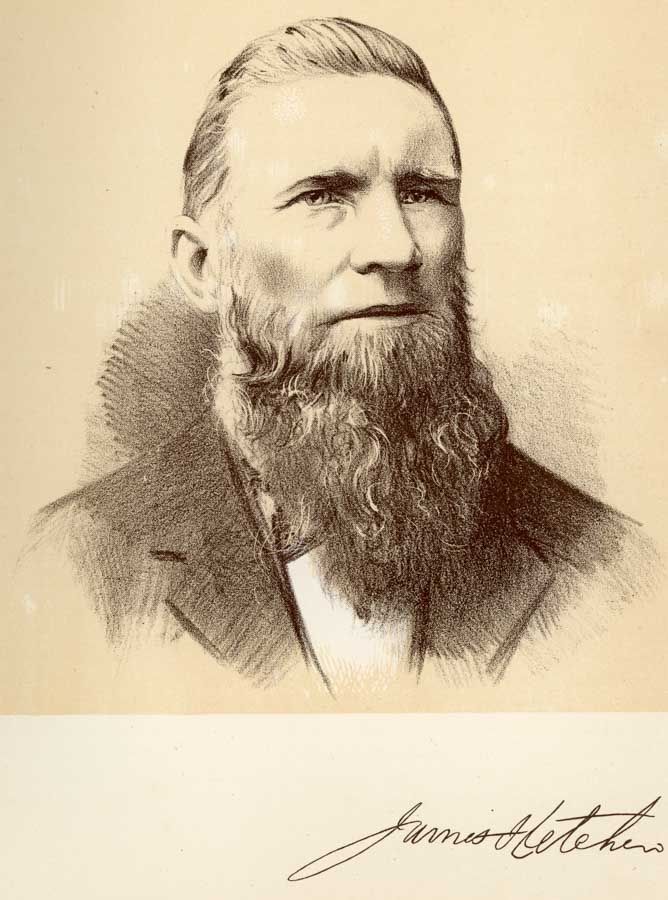

JAMES Fletcher’s name has become synonymous with the foundation of The Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate. The Scottish-born former miner, mining union leader, mine manager, mine owner and Member for Newcastle may not literally have founded the newspaper, but he was its proprietor during some of its crucial early years and he used the paper to powerfully influence the progress of the coal industry.

Fletcher migrated from Scotland in 1852 at the age of 18 and, after an unsuccessful attempt to make his fortune in the gold rush, came to Newcastle to work coal, finding a niche as a clever and influential union leader. He became the first chairman of the Coal Miners’ Association, which later grew and became the mighty Miners Federation.

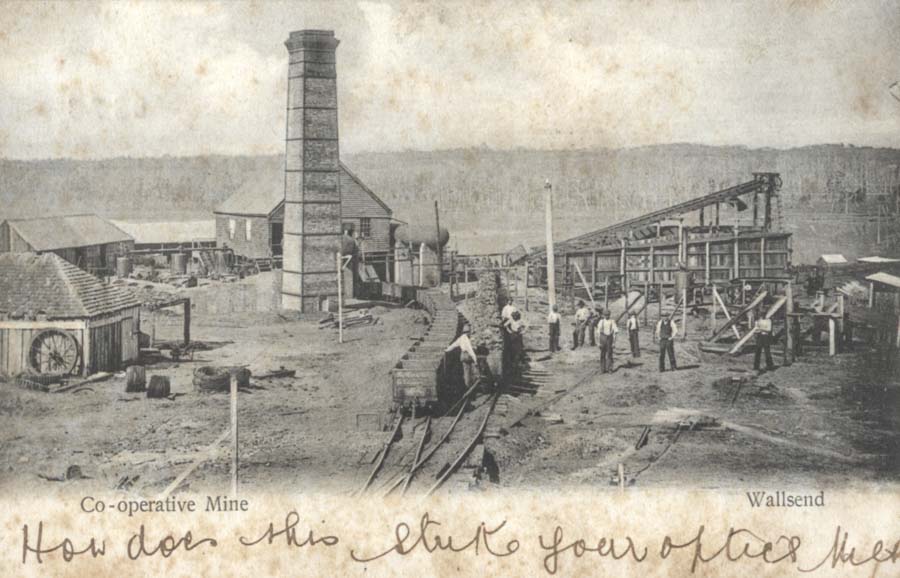

In 1861 Fletcher and some other miners made a brave attempt to start their own mine, the Co-Operative Colliery at Wallsend, but the venture was ill-timed and an oversupply of coal led to low prices and the mine was taken over in 1869 by its mortgagee, the wealthy William Laidley. Laidley pumped in money to make the mine more efficient, leaving Fletcher as manager with a free hand to run it.

During this period, Fletcher became a frequent correspondent to newspapers, under the pen-name “Argus”, advocating market-control measures to alleviate low prices and low wages in the coal industry. In 1872 and 1873 he was instrumental, as a mine manager, in introducing the “Vend” – a deal between mine owners to keep prices high – and a “sliding scale” linking miners’ wages to the selling price. Without the deal, the mining companies were cutting each others’ throats for market share, risking pit closures and job losses. The deal was made, and since it coincided with fortunate economic times, Fletcher won great credit from all sides for his role as broker. Certainly, the deal helped Newcastle on the road to prosperity.

Courtesy of Reg Pogonoski.

Also in 1873 Fletcher’s future son-in-law, Maitland-born journalist and printer John Miller Sweet, was persuaded by some miners to start a newspaper in the mining boom town of Plattsburg (Wallsend). The Miners’ Advocate’s appearance was a poke in the eye to the powerful mining companies and their perceived unfair dealings with employees and communities.

But by backing miners and their families against the rich and influential coal proprietors the Advocate made dangerous enemies. It had some remarkably bad luck when the newspaper’s office was burnt down while Sweet was out of town. To rub salt into the wound it occurred to the authorities to charge Sweet himself with being involved in the apparent arson attack. The case against Sweet dissolved through lack of evidence, but the business’s insurers wouldn’t honour their policy and Sweet ran out of money. Undaunted and with financial help from many supporters he set up again and the Advocate was reborn. Almost immediately the mighty J and A Brown coal dynasty attacked the paper via a libel case in the name of one of its mine managers whom the paper had accused of treating two miners unfairly. The newspaper lost the case, but a sympathetic court fixed the damages at one farthing.

Birth of The Newcastle Herald

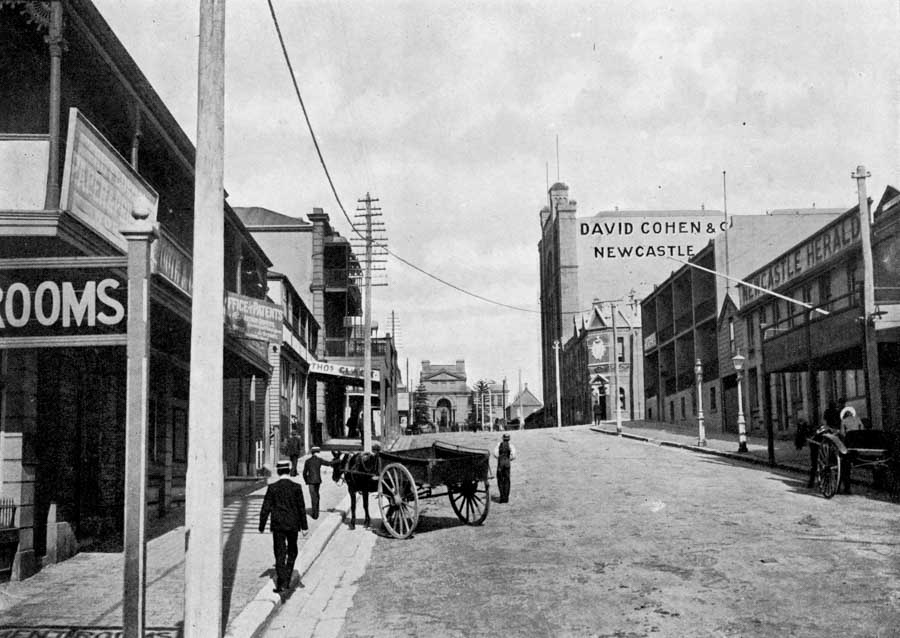

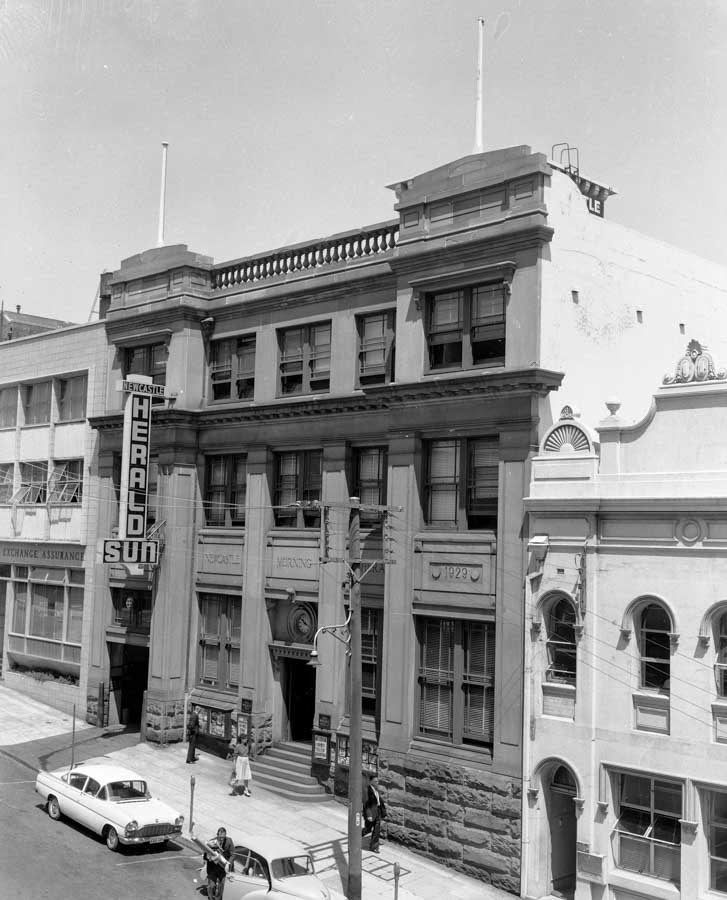

John Miller Sweet married James Fletcher’s daughter, Mary Ann, the following year. It seems clear that Fletcher saw a great opportunity to use the newspaper to promote his own views on maintaining the coal industry’s profitability. In 1876 Fletcher encouraged his son-in-law to shift the Miners’ Advocate printing equipment from Plattsburg to Bolton Street, Newcastle, to produce a new daily paper for Fletcher – The Newcastle Morning Herald, incorporating The Miners’ Advocate. The Herald’s original office was next-door to the offices of the Commercial Banking Co of Sydney on the eastern side of Bolton Street.

The Newcastle Morning Herald’s first editorial laid out its projected policy:

“We are not the tools of the capitalist nor the hirelings of the working man, but co-workers with them both. We care for no government and we fear no party. Finally, we stand for that which we believe to be right and smite hard at that which we believe to be false.”

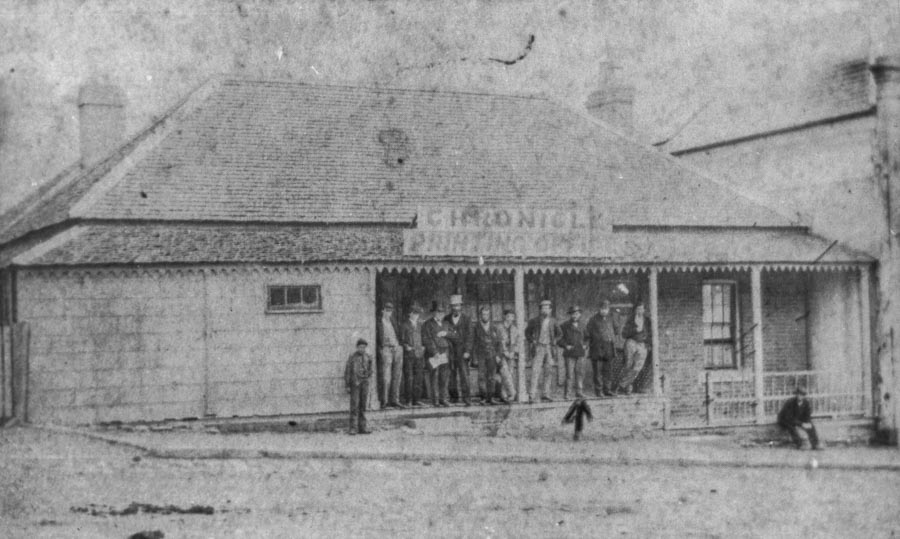

After a few months in business the new paper took over its main rival, The Chronicle, shifting to the older paper’s premises on the western side of the street, where the paper remained for many years.

Reminiscing in later life on the subject of “the Vend”, Sweet recalled a meeting at the office of the Advocate where coal owners offered Fletcher a big reward if he could persuade the miners to accept the sliding scale wage proposal, which was a powerful deterrent against strikes.

A noted Herald journalist of the time, James Inglis, wrote years later that in his work on the paper he “did not meddle with the coal question or purely mining matters; they were manipulated by experts and there was a good deal of wire-pulling and puppet-dancing”.

Sweet became ill and at the end of 1877 he had to borrow money from his father-in-law to stay afloat. It was at this time that Fletcher emerged unambiguously as The Herald’s proprietor. Sweet resigned as manager in 1879, threatening to expose his reasons for leaving by way of a court action. No action eventuated and he soon resumed his job as manager.

Opposition to foreign wars

In 1880 Fletcher was elected Member for Newcastle. In Parliament, he was not afraid to voice unpopular views. In 1885, when Britain sent an expedition to the Sudan, Fletcher worried about the precedent if New South Wales sent troops to fight.

“Can anyone say where this sending of our men to fight in a foreign land will end, or what the expense may be?” Fletcher asked. By sending troops to the Sudan, the colony had “published to the world that New South Wales is prepared to assist in fighting the battles of England whether England is in the right or in the wrong”. By the end of The Great War, in 1919, his words might have seemed prophetic.

Research by amateur historian Dulcie Hartley suggests that Fletcher’s takeover of Newcastle’s paper was probably financed by a consortium of coal owners who believed that the former union leader’s credibility and influence at the city’s daily news sheet was good for their business. But after a falling out with coal baron John Brown in 1884, Brown’s father James demanded repayment from Fletcher of £3500. Fletcher lost the highly publicised court case, after much evidence on the manner in which his newspaper advocacy had helped enrich the coal owners to the tune of tens of thousands. Coal owner Alexander Brown told the hearing that Fletcher had performed a valuable service for the money advanced. Fletcher’s “advocacy was of great value to the firm as the paper exercised great influence over the miners and did, in fact, keep up the price of coal for years”.

A public whip-around paid Fletcher’s court bill but he didn’t remain proprietor of The Herald much longer. He sold out in 1888 to a group of local investors.

During his time at The Herald Fletcher campaigned passionately for many causes: free education, electoral reform and social equity were some of them. Also high on his list was a desire to see Newcastle treated fairly by the Sydney-centric government of the time.

Even in the 1870s the Hunter Region was the great wealth-producing hub of NSW, but the residents of the district complained that little of this wealth was returned by the Sydney masters, who were content to watch Newcastle struggle by with no water supply, poor parks and facilities and a myriad other inconveniences which would never have been tolerated in Sydney.

Fletcher used The Newcastle Morning Herald to argue, forcefully and repeatedly, for improvements at every level. Fletcher is described as “pacing around The Herald office, hands clasped behind back dictating an editorial”. And his editorials could be fiery. One unfortunate Member of Parliament he described as “a hare-brained madman” and “a spiritless, grovelling nonentity”.

Bitten by the gold-bug

Through Parliament, The Herald and through many other channels, Fletcher won many successes. He is credited with helping win improvements to the port of Newcastle, to eliminating punitive wharfage dues which were seen as discriminatory against Newcastle, helping push the state government to provide a water supply to the town, forcing the construction of public buildings and ending the menace to Newcastle from the dreaded sand-drift that once threatened to engulf it.

Fletcher also managed to enjoy a very full social life, often subsidised – one way or another – by his coal industry connections. He lived in a splendid house, Styles Grove, built for him by mine owner Laidley. He was a property investor and he owned a racehorse and greyhounds. He never recovered from the gold bug which bit him in his youth and when gold was discovered at Copeland in the 1870s he was involved in several mining syndicates. According to Mrs Hartley, it was an injudicious investment in yet another gold venture which cost Fletcher his fortune in the end.

When Fletcher died in 1891 The Wallsend and Plattsburg Sun commented:

“Nothing else was talked of all day and yesterday . . . [his] loss is regarded by our people as a national calamity – national because he was the friend of the poor and needy, the friend of the labouring classes, the exponent of truth and justice and the opponent of tyranny, monopoly and chicanery . . . [he] did much towards the advancement and development of the coal industry, and more for the miners . . . [he] fought in the cause of labour at all times and in all places.”

Thousands attended Fletcher’s funeral and a statue was erected in his honour on the Lower Reserve, in Newcastle. An account of his funeral can be read here.

Such an interesting, easily read story surrounding a local landmark and Newcastle identity. I have driven past the statue many times over the years and not taken the time to investigate. I believe my grandfather was very disenchanted with Mr Fletcher, when explaining the existence of the statue to me as a child, in the early 50’s. However, with the luxury of hindsight and a more ‘global’ view today, Fletcher appears to have made a valuable contribution to the mining industry and the wider Hunter community than I would otherwise have realised.

Thank you.

Thanks for the comment Ken. I’d like to know why your grandfather had a beef with Fletcher.

Cheers,

Greg