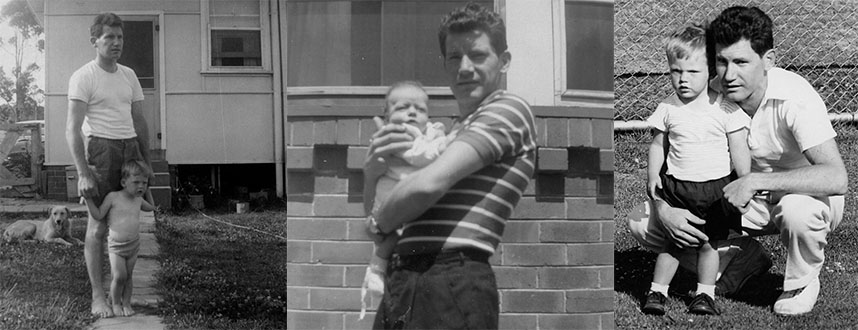

His big safe hands I remember most of all. His fingers seemed huge to me and I felt his frustration when, working on the engine of a car or some other repair job, these unwieldy fat sausages would drop an important nut or washer into some inaccessible spot while attempting to fit it where it belonged. I’d volunteer to do the job with my small, precise child fingers but he would seldom hear of it. My job was just to be present and maybe, like a surgeon’s assistant, sometimes hunt for a half-inch ring spanner or a Phillips-head screwdriver or for some tiny screw that had bounced away into the grass near the carport.

He was always making things and he usually succeeded at his tasks, though sometimes the results were inelegant. His style was to push through. He designed things with the eye of an engineer, with a fat safety margin and no embellishment. Strength was in his hands and perseverance in his nature.

He was a natural at almost any sport. His eye-hand-co-ordination was marvellous when it came to finding a moving ball in space. He could throw a ball accurately with great force and catch one with nonchalant precision. Soccer, league, tennis and golf were easy for him and he loved the field of contest. Athletic, fit and strong he was restless and always on the move.

He smelt of California Poppy hair oil, which made his short curly black hair glossy. His chin was rough with stubble except immediately after a shave when he also smelt of Old Spice, or Cobb & Co, or some other pungent after-shave lotion. These smells are locked into my early childhood memories of him, along with the alien metallic scent of industrial overalls, petrol, beer, Dencorub and underlying it all, his indefinable vigorous maleness.

His roots were in a world that would never be mine. There had been a war. His father had been over there. His family was short of money and his mother made ends meet. No shoes for school. His sister’s hand-me-downs. Clamouring for apple-cores from the rich kids. Boys’ high school. Soprano in the Gilbert and Sullivans. Failed his leaving certificate. National Service. Nearly died when his appendix burst. Fitting and turning apprenticeship then a job in the drawing office. He said his father didn’t really like him and called him effeminate. He wasn’t Saint Aloysius, he told me. Met my Mum at a dance. Sweethearts almost immediately. Engaged for ages. Eventually got her pregnant and his Mum told him off about it. My Mum never quite forgave him and he knew it. I was his mistake, apparently.

My father was dependable and I had the luxury of being able to take that for granted. Those big hands were there to help me and they always did. When I was scared of monsters in my room he drew and coloured a poster of a tiger to frighten them away. It worked. He played games with me. Ball games, board games and silly games. He bought me little toys and Batman bubblegum cards on his way home from work. At night, when I got the terrors or my legs ached from growing pains he was there to ease the fears or rub the pain away. He made up silly songs and called me funny names. He wanted me to be a good cricketer and he took me to a store to choose the best bat he could find. Lovely piece of willow with good clean straight grain and a wonderful flexible cane handle. Soaked it in linseed oil. Practice though I might, I never did justice to that bat. I still have it.

He could pull motors apart, fix them and put them back together. He was systematic and careful. Being task-oriented he was happy to have a challenge and when one job was finished he was looking for the next one. He loved watching sport on TV and listening to it on the radio, even at mealtimes. He barracked for Eastern Suburbs in the Sydney league competition.

People liked my father. So did dogs. He had a kind of charisma. He made friends and often kept them. He liked a beer or three and a barbecue on Sunday when neighbours would come over.

He tackled projects that seemed absurdly large to my eyes but he demonstrated that even one person working alone could do huge things if they followed the simple formula which was to start and keep going. He seemed to thrive on hard work and sweated in the sun, digging post holes or mixing concrete with a garden spade or painting the house or digging out clay for a swimming pool he decided we should have.

My father roped me into sport and I’m glad he did. I liked playing soccer, though he stood on the sidelines and roared at me to “tackle, don’t be scared of him” or “stop daydreaming and follow the ball” or unflatteringly declared that I was “running like a fairy”. Apparently unable to find the money for shin-pads he stuffed Readers Digests down my socks but they always worked their way around to the back.

I could write, if I chose, my assessment of my father’s failings. But what would be the good of that? My father is dead, like all the other men in the generational line behind him and like my younger and only brother. Although I think about my father almost every day the only place we talk is in occasional dreams when he appears, usually to take me to some place in the land of dreams he thinks I might like to see. Recently I dreamed he appeared in the form of a large lizard, telling me he’d be seeing me soon. Soon, sooner or later: what’s the difference anyway?

Eulogising fathers in general is not a thing I want to do. With three adult children of my own I can see the fallibility of fathers all too clearly from the inside, and I understand now how even the very best of intentions don’t always add up to success in our own eyes or in those of our children.

My father wanted me to know him and I wanted that too. Of course I knew him, but with reservations. There was always a barrier in the way, somehow. I could never really enter his world and I knew that he could never really enter mine. And yet he was to me a good father and I look back at him with feelings of love, kindness and gratitude that are not diminished by any failings. I learned many lessons from him, the best of which were taught by example.

I remember his hands most of all. Big, safe and true. I never knew those hands to act meanly or with dishonesty in all the years I saw them working in this world. They acted unwisely sometimes, and sometimes with unintended cruelty. I saw the cost of those mistakes.

Shortly before he died, with tears in his eyes and his voice thick with emotion, he told me that although he had promised not to make the mistakes of his own father, he had – despite himself – repeated some of them. He and I both understood his meaning, and I respected his late acknowledgement.

As he lay dying my father, half-delirious, said he could see my dead brother – sometimes in the open, sometimes waving to him, sometimes half-hiding from him.

My mother said that when my father died, she saw a subtle ball of light lift from his body and move away. I believe her.

May he be at peace.

That’s a great piece of writing Greg and all too close to my own experience in the sixties back in ol’ Kotara,, not too many years before yours. It resonates almost painfully and threatens to tear me up – but I won’t, I’ll play the hard nut, as our generation were conditioned to do.

Enjoy your Fathers’ Day Greg. I’m not a father of anyone but I can still feel your pain and your joy and elation. Thank you.

Cheers,

Paul

Thanks very much Paul. I appreciate your comment.